Using Culturometrics to Assess Undergraduates' Levels of Foreign Language Enculturation: A Wake-up Call

Béatrice Boufoy-Bastick, West Indies

Béatrice Boufoy-Bastick lectures in French and TESOL at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad. She has wide cross-cultural experience and is the author of numerous publications in the area of language and culture. Her research has led to the development of Culturometrics - a new field in culture research. E- mails: bboufoybastick@gmail.com, beatrice.boufoy-bastick@sta.uwi.edu

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Background

Assessment imbalance in subject enculturation

Language identity and its measurement

Methodology

Results

Conclusions

References

A major psycho-pedagogical objective of foreign language teaching is to enculturate our students into the cultural values of native speakers. However, foreign language educators have no objective measure of the extent to which this objective is attained. Traditionally foreign language assessment seeks primarily to measure grammar skills and content knowledge. It tends to ignore assessment of the affective dynamics that alter learners’ identities. This omission is no evidence of educators’ disregard towards the affective components of foreign language learning. It is rather an attestation to the difficulties of assessing degrees of enculturation, that is the extent to which the students have internalised the values inherent to the culture of the discipline. Difficulties in assessing enculturation, or more specifically the changes in cultural identity relevant to the target language, lie partially in the elusive meanings of ‘cultural identity’. Cultural identity has simplistically and reductively been defined in crude terms of ethnicity rather than in degrees of cultural allegiance, thus confounding cultural identity with ethnic grouping.

This paper reports on an aspect of a study which explored the changing cultural identity of French undergraduate students at UWI St. Augustine campus, Trinidad. While cultural identity of Trinidadians is shaped by inter-ethnic mixing and its associated cultural borrowing of selected behaviours, this is further compounded for Liberal Arts students at UWI who are also exposed to pedagogic enculturations through reading for a degree in French or Spanish. What is reported here is how exposure to French and Spanish language, and associated pedagogically embedded influences on cultural identity formation, shapes language students’ increasingly complex composite cultural identities over the four years of their degree programmes. The findings derive from survey data collected between 2007 and 2009 (N=231). The paper also presents a novel Culturometric methodology used to measure cultural identity profiles of language students in Liberal Arts.

Teaching aims at increasing student affective and cognitive attainments. These two components are inseparable and always present in our teaching in differing amounts. For the cognitive component we teach and assess skills in facts and processes, with the aim of imparting competence in our subject to our students. For the affective component we teach values, feelings and attitudes, with the aim of imparting the culture of our subject to our students. Accountability requires that we use objective assessments to measure increased attainments. We have objective measures of cognitive attainments so we teach and assess skills, facts and processes and because learning is driven by assessment, our students are motivated to learn these skills, facts and processes. We do not have objective measures of affective attainments so we teach but do not assess values, feelings and attitudes. Hence, because learning is driven by assessment, our students are not so motivated to learn the culture of our subject and some do not. Consequently, despite our best intentions we graduate Doctors who are uncaring, Lawyers who are unethical, Accountants who are dishonest,Teachers who dislike children and, as is the focus of this paper, Language graduates without a target culture. The root difficulty thus lies in defining and objectively measuring the culture of the subject. In response, this paper introduces a Culturometric solution for objectively monitoring the subject relevant cultural identity of students. The method can be used to ensure that the teaching of subject culture is increasing the affective attainments of our students. The method is demonstrated by assessment of the target language identities in a cross-sectional study of N=231 students enrolled in French and/or Spanish courses in the Departmentof Liberal Arts. The results are consistent with the ‘hidden curriculum’ and show that the language identities of our students in their culture of their target languages of French and Spanish drops significantly over the four years of our teaching. Culturometrics is also used to identify respondents for interview so that we can explore the detailed meanings and causes of this ‘wake-up-call’ to our language teaching.

Education has identified two fundamental overlapping learning attainments: the mainly analytical (separate, highly compartmentalised) skill-based knowledge of facts and processes and the mainly affective (holistic, integrated) purposes and intentions of learning (Brown, Birch, Thyagaraj, Teufel, & Phillips, 2007; Clark, Sauter, & Kotecki, 2000; Maine, Shute, & Martin, 2001; Ogletree, Hammig, Drolet, & Birch, 2004). These are most explicit in vocational Higher Education programmes in which we teach and assess students’ expert technical knowledge of facts and processes and in which we model the professional attitudes values and intentions of the expert practitioner (Fayolle, & Degeorge, 2006; Roxas, Cayoca-Panizales, & de Jesus, 2008; Souitaris, Zerbinati, & Al-Laham, 2007; Ytterberg, Plotnikoff, & Harris, 1998). Although we highly value professional attitudes, unfortunately we only pay lip-service to the assessment of students’ professional attitudes, values and intentions (Lindemann, & Soule, 2006; Shah, Anderson, & Humphrey, 2008). This is mainly because we have objective assessments of skills that satisfy our accountability requirements and drive student learning but we have an assessment deficit in objective measures of values. For example, in writing on ‘The Assessment of Professional Competence’ Michael Kane (1992,), has observed:

“Valid assessment of professional competence has proven to be an elusive goal. Objective tests, direct observation of performance, overall ratings of competence, and simulations have been tried and found wanting in one way or another. Objective test items are criticized as being unrealistic and therefore invalid. Direct observation tends to be very unreliable and therefore invalid. Simulations and overall ratings of competence share both of these flaws to some extent. Basically, you can't win.” (p. 163).

Similarly, Van Der Vleuten (1996) noted that “The search for instruments to assess clinical competence has been stimulated through emerging logistical constraints and the dissatisfaction with ongoing assessment practice in the health sciences.” (p. 41). Likewise, Crossley, Davies, Humphris, & Jolly, (2002), summarise, “Unfortunately, there are few objective tests for the most important aspects of the professional role because they are complex and intangible. In addition, professional performance varies markedly from setting to setting and case to case. Both these factors threaten reliability.” (p. 927). Hence, we are in danger of passing highly skilled students with less than appropriate professional values.

Public examples of this concern in Higher Education are readily found in vocational courses such as Medicine, Nursing and Education. As Cruess and Cruess (2006), say “The public must be assured of the competence and character of graduates of both undergraduate and postgraduate programs.” (p.207). We want skilful doctors who are also motivated by the Hippocratic Oath (Beauchamp, 2004; Royal College of Physicians of London, 2005). We want practised nurses who are also sympathetic to their patients (Ke, 2008). We want knowledgeable teachers who also care for the futures of our children (Schwartz, & Lederman, 2002).

The focus on objective assessment to the detriment of values attainment has caused concern at all levels of education. Examples that attain less public attention abound at all these levels of learning. For instance, Kelleher (2003) has reported: “With the increasing expectations for students, manifested through state-wide standardized tests in nearly every state and the development of curriculum frameworks throughout the country, a heightened interest in both spending for professional development and the effect of adult learning on student learning has emerged. In addition to these shifts in focus, current research is redefining our notion of professional development.” When we teach children the curriculum skills we also endeavour to share the joys of reading, the wonders of mathematics, the discoveries of geography, the options of history and the possible futures of science.

Full enculturation into the subject requires attainment of skills and of values. However, under increasing requirements of accountability formal education has emphasised objective skills assessment because we have few, if any, objective assessments of values that would satisfy formal rigours of accountability; yet universities are reluctant to focus on the matter (Cruess, 2006; Sambell, & Mcdowell, 1998; Thomson, 2001). At the school level, this assessment deficit is a central focus of movements for ‘values education’ (Aspin, & Chapman, 2007; Lovat, & Toomey, 2009; Anderson, 2007). In Higher Education, this assessment deficit is of critical concern in medicine where students can obtain high grades in objective skill assessments yet lack the decorum, the morality and the humanity expected of the medical profession. In his paper questioning .. ‘Are we serious about teaching professionalism in medicine?’ Saultz (2007, p. 574) observes that “Medical professionalism is an increasingly common topic of discussion in the medical education literature. Much of the recent literature on this subject addresses areas of weakness in the educational curricula of medical schools and residency programs.” Similarly, Fryer-Edwards and Baernstein (2004) write “The renewed attention to professionalism is not surprising given the laundry list of challenges that medicine has faced in the past few decades. With each report of medical errors, conflicts of interest, and inhumane training situations, patients are beginning to wonder if physicians are capable of acting in their best interests.” (p. 22).

It is equally true in language education, but having less risk-attachment this has previously been mainly a specialist pedagogic concern. However, growing international cultural pressures to maintain language identities in the confluence of global economic exchanges (Preisler, Fabricius, Haberland, Kjaerbeck, & Risager, 2005) has now led the European Union to formally propose cultural inter-comprehension assessments for language learners that emphasise shared values over traditional language skills (Araújo E Sá, & Melo, 2007; Phillipson, 2002; Slivenskya, 2008).

Accountability needs introduce two problems that stymie objective assessment of subject-values, (i) finding a consensus to define the subject-values, and (ii) developing equitable assessments of those subject-values. The purpose of the research presented here is to contribute to the re-emphasis on values learning by developing accountable objective methods of monitoring students’ affective attainments in their subject areas (Ginsberg, & Stern, 2004; Wear, & Kuczewski, 2004). In particular, consistent with the literature on communities of practice which emphasises the importance of the enculturation of beliefs and identity in learning (Kjaerbeck, 2005; Lemke, 2002; Lin, 2008; Riley, 2007; Wenger, 1998), we consider skills learning plus values learning as a process of enculturation into the culture of the subject, and assess that enculturation by measuring changes in subject-cultural identity of the student. This paper addresses this area of enculturation in Modern Language education.

Why do we prefer language teachers to be native speakers? It is because...“language, culture, and identity are intertwined” (Shiels, 2001, p. 431). As the great Edward Sapir said in his now classic work on ‘Language, Race and Culture’, “Again, language does not exist apart from culture, that is, from the socially inherited assemblage of practices and beliefs that determines the texture of our lives.” (Sapir, 1921, p.221)

As Modern Language teachers, it is incumbent upon us, sometimes by law (Liddicoat, 2005), to enculturate our students into the skills and values of the target language by necessarily addressing both skills attainment and cultural attainment (Byram, & Feng, 2005; Dlaska,2000; Met, & Byram, 1999; Minami, 2004; Paige, Jorstad, Siaya, Klein, & Colby, J. 2003) .

“Studying a foreign language is more than a simple task of decoding. The teacher must communicate to her students that the study of language is also a study of people and cultures, because language is an integral part of a culture” (Rowan, 2001, p.238)

We teach and objectively assess the.vocabulary, grammar ..and skills of the language. By our choice of cultural content, by our behaviour manner and dress, by organising plays in the language, through international visits and Internet technology, etc. etc. we also teach and model the target culture, but we do not objectively and summatively assess our students’ attainments in the values, attitudes and intentions of the culture that we are so teaching (Boxer, & Cortés-Conde, 2000; Donaldson, & Kotter,1999; Rowan, 2001). Conversely, it is often a cultural identification with our subject that motivates students to enrol and continue in our language programmes (Bruna, 2009). As a large component of student learning is assessment-driven, we might find that rather than promoting enculturation, we are in danger of undermining our students’ cultural identification by focusing only on skills assessment (Genc, & Bada, 2005: MacDonald, Badger, & Dasli, 2006; Stern, 2005). This danger has been recognised by the current EU GALANET platform for developing inter-comprehension under the Socrates Programme which proposes the drastic solution of assessments that emphasise cultural competence at the expense of language proficiency. In this research, we demonstrate a more positive approach to support both skills attainment and cultural attainment in language enculturation (Andrade, Araújo e Sá, Lopéz Alonso, Melo, & Séré, 2005).

In this paper, we demonstrate objective Culturometric (CM) methods of monitoring students’ cultural attainments in language enculturation and use these methods to measure whether our teaching of Spanish and of French is enhancing or undermining the enculturation of our language students.

Research respondents and research design

This is a cross-sectional study. Our respondents were N=231 students enrolled in French and/or Spanish courses in the Department of Liberal Arts. As the Department has a relatively small number of modern language students, these respondents represented an incomplete population census rather than a statistical sampling of language students. The respondents comprised 122 first-year, 46 second-year, 55 third-year students and 2 fourth-year students with 6 students having missing year values. Thirty-two were male, 190 were female and 9 protocols had missing gender values. There were 21 French majors, 55 Spanish majors, 77 taking French and Spanish, 58 reading English, 7 Linguistics and 11 others with 2 respondents having missing major values.

We used the Cultural Index (CI) methodology to assess the French, Spanish and Ethnic components of their cultural identities and, for validity testing we noted their Religions. The study was in four stages, briefly described here and then described in sufficient detail for replication below. The first three stages were quantitative and the last stage was mixed-methods.

Stage 1 (a) Data cleaning using two-tailed exclusion of non-consistent respondents, and (b) identification of optimal public objects for calculations of ethnic and language cultural Indices.

Stage 2 Reliability and Validity: (a) Test-retest correlations were used to assess reliability of responses. (b) Religion and strength of Ethnic Identity were used to assess the construct validity of the cultural identity measurements.

Stage 3 Year-by-year changes in students’ French and Spanish cultural identity components: French and Spanish cultural identity components were compared across the three annual cohorts of respondents in a cross-sectional design.

Stage 4 Meanings of French and Spanish cultural identity components: Students were sorted on the two dimensions of their Spanish and French cultural identity components. Students who had contrasting high Cultural Identity on one language and a low Cultural Identity on the other language were selected for highly focused topical interviewing.

Instruments and administration

The researcher received permission to administer the following questions to intact classes of language students. The quantitative questions were embedded in a larger confidential test battery. All respondents answered the questions at least once. 14 students were selected on the ad hoc basis of their class enrolments to answer the questions twice. The average duration between the test and re-test for these 14 students was 8 days.

| Sex: (circle correct response) Male or Female |

Circle your Religion

Protestant

Catholic

Muslim

Hindu

Jewish

None

Other (please name )

|

| You are a 1st / 2nd / 3 year student (circle correct response)

|

Your judgement ...

Please show your judgment by giving a number from 0 to 10

(0 means not at all and 10 means the maximum)

On a scale from 0 to 10…

|

How Indian do you feel (0 to 10)?

|

|

How African do you feel (0 to 10)?

|

|

How Spanish do you feel (0 to 10)?

|

|

How French do you feel (0 to 10)?

|

|

How Indian is PM Patrick Manning (0 to 10)?

|

|

How African is PM Patrick Manning (0 to 10)?

|

|

How Spanish is PM Patrick Manning (0 to 10)?

|

|

How French is PM Patrick Manning (0 to 10)?

|

|

How Indian is calypso (0 to 10)?

|

|

How African is calypso (0 to 10)?

|

|

How Spanish is calypso (0 to 10)?

|

|

How French is calypso (0 to 10)?

|

A repeated block design was used to elucidate the students’ meanings of French and Spanish Language Identities, each student representing a block. Six students with the most contrasting high and low language identities were selected for oral interview and asked the following four questions in random orders. After the oral interview the students were asked to summarise in writing their answers to the same four questions in the following order.

- In what ways do you think you are French

- In what ways do you think you are Spanish

- In what ways are you not French?

- In what ways are you not Spanish?

Methods of analysis

Stage 1 (a) Data cleaning using two-tailed exclusion of non-consistent respondents

A problem with self-report data is how to identify, for alternative analysis or for possible exclusion, respondents who have not used their values consistently. A technique of Culturometric CI regulators called ‘Value consistency’ is designed for this purpose. CI regulators use a simple and intuitive projective-rescaling technique to elicit and ground privileged information from subjective judgements that can then be more rigoursly analysed. The subjective judgements are ratings evidencing values in context which define identity. Cultural Index (CI) regulators can optionally utilise three questions. Question 1 is a self-rating of the cultural construct in the identity of the respondent. Questions 2a and 2b are ratings of the same cultural construct in the identities of two public objects. All three responses should be consistent applications of the respondent’s same values to these three different contexts. More public objects could have been used for greater rigour but two was considered sufficient for this study. In this research on language identity, the researcher was using the emic consensus of the whole group to operationally define the cultural constructs, and to ground each respondent’s self-ratings. Thus, the mean rating of Q2a defined the ‘true’ degree of the construct in public object ‘a’ and the mean of Q2b defined the ‘true’ degree of the construct in public object b. Therefore, the mean of Q2a divided by the mean of Q2b represented the ‘true’ ratio of the cultural construct in the two public objects. Now, although respondents were likely to over-rate or under-rate the cultural construct according to their idiosyncratic values, if their values were consistent with those of their group and were applied consistently then a respondent’s individual Q2a/Q2b ratio would have been similar to the ‘true’ group ratio, and in that case we could infer that their Q1 self-rating was also likely to have been consistent. As a rule of thumb, considering our respondents’ compliance and data set size, we set the higher bound at 200% consistency and the lower bound symmetrically at 50% consistency – that is, as the choice of numerator and denominator was arbitrary we used the symmetry that the 200% bound for Q2a/Q2b was equivalent to the 50% bound for Q2b/Q2a. In this study the two public objects were the then Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, the Honourable Patrick Manning and Calypso music which is symbolic of Trinidad.

All ratings of the cultural construct for respondents whose value consistency fell outside these bounds were set to ‘missing’. To better maintain our ‘sample size’, missing values were excluded pair-wise from subsequent calculations, rather than list-wise or case-wise,. One was added to each 0 to 10 rating to avoid division by zero, thus re-scaling the rating to be between 1 and 11. This adjustment would have most affected results that used the extreme ratings, which were more likely to have been nominal principled responses rather than the required more discriminating ordinal responses. However, the possibility of such affects was minimised as these extreme principled responses were likely to have been excluded as examples of inconsistent application of the respondent’s values.

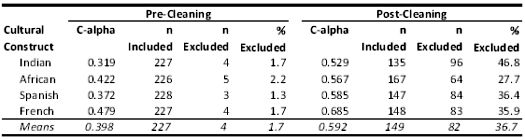

C-alpha is a whole dataset measure of how consistently high or consistently low are the responses of each subject. After data cleaning by removing subjects’ inconsistent responses, we expected an increase in C-alpha for each cultural construct, even though subjects only gave three responses for each construct. For each of the four cultural constructs, Indian-ness, African-ness, Spanish-ness and French-ness, we assessed the cost-benefit of this data cleaning in terms of the benefit in increased C-alpha and the cost in terms of loss of data points due to excluding inconsistent responses.

Stage 1 (b) Identification of optimal public objects for calculations of ethnic and language cultural Indices.

To choose the better public object for calculating each cultural index we used the two-stage rule of thumb and triangulated with the standard k-s decision rule. The first stage minimised ceiling and floor effects by choosing the public object whose mean was closest to the middle adjusted rating of (1+11)/2=6. The second stage was applied only if the means were close together, and in that case the public object whose ratings had the smaller standard deviation was chosen so as to privilege the greater group consensus that the smaller standard deviation signified. However, results of these rules-of-thumb were also checked with the standard k-s decision rule that used the single sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Z statistic to choose the public object that had the more Normal distribution of ratings.

Stage 2 (a)Test-retest correlations were used to assess reliability of responses.

The test self-ratings and public object rating of Indian-ness, African-ness, French-ness and Spanish-ness from the 14 test-retest respondents were correlated with their re-test self-ratings and public object rating of the corresponding cultural constructs on the retest.

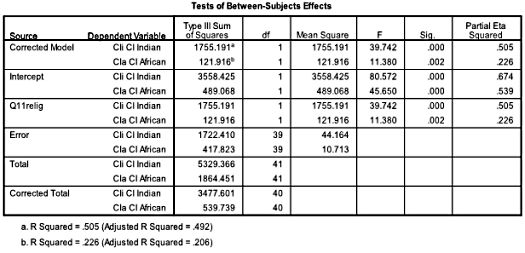

Stage 2 (b) Religion and strength of Ethnic Identity were used to assess the construct validity of the cultural identity measurements.

If the cultural identity measurements have construct validity we would expect that the ethnic identity of respondents who were Hindu to be considerably more Indian than African, whereas the ethnic identity of respondents who were Catholic would tend to be more African than Indian. We calculated a MANOVA to test these two hypotheses.

Stage 3: Year-by-year changes in students’ French and Spanish cultural identity components

To explore any changes in French and Spanish cultural identity components over the four years we used error-bar plots of mean CIs for the four years and ANOVAs with post-hoc contrasts comparing year means pair-wise.

Stage 4: Meanings of French and Spanish cultural identity components:

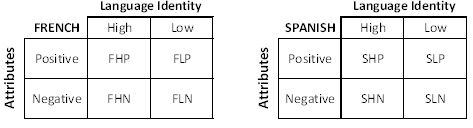

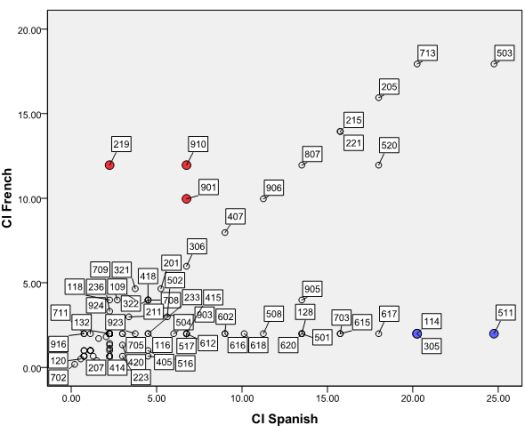

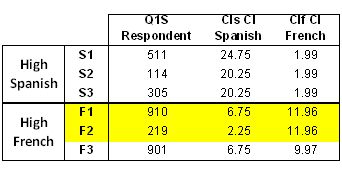

Respondents were ranked on their French and Spanish cultural identity components using a case labelled scatter-plot so that six respondents high on one CI but low on the other CI could be selected for oral interviews utilising the four interview questions above. The recordings were transcribed and together with the written summaries were analysed using NVivo 8 in a 2x2x2 comparative qualitative comparison repeated block design for French and for Spanish shown in figure 1, each respondent being a block.

Figure 1: Mixed methods - Repeated block design for qualitative comparisons

Stage 1 (a) Data cleaning using two-tailed exclusion of non-consistent respondents

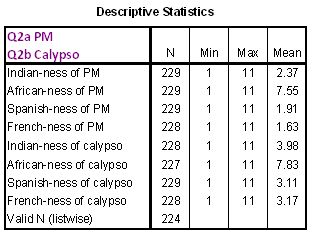

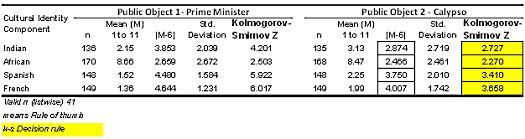

Table 1 shows the mean consensus values for each cultural identity component for public objects Q2a and for Q2b.

Table 1: Consensus values for cultural identities of public objects

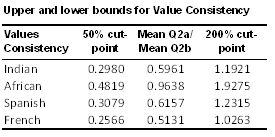

Table 2 shows the ‘true’ proportions of the group means for each identity component. It also shows the lower bounds and upper bounds for Value Consistency as 50% and 200%, respectively, of these ‘true’ proportions.

Table 2: Value Consistency set between 50% and 200%

Table 3 shows the cost-benefit of data cleaning using the CM technique of Value Consistency

Table 3: Cost-benefit of Value Consistency cleaning

It is seen from Table 3 that the cleaning increased the mean C-alpha consistency by an average of 50% for a cost of an average increased exclusion of 35%.

Stage 1 (b) Identification of optimal public objects for calculations of ethnic and language cultural Indices.

Table 4 shows agreements between the rule-of-thumb and k-s decision criteria for the choice of the more appropriate Public Object based on the Normality of only Value Consistent responses. The numbers shown in the ‘n’ columns are considerably reduced from the corresponding ‘N’ in Table 1 due to the two-tailed loss of inconsistent responses. This result shows that the ‘Calypso’ Public Object was the more suitable for the calculation of all four Cultural Indices.

Table 4: Rule-of-thumb and k-s decision criteria for the best choice of a Public Object

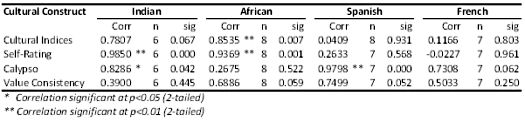

Stage 2 (a)Test-retest correlations were used to assess reliability of responses.

Table 5 shows the test-retest correlations for the raw self-ratings and ratings of the Calypso Public Object as well as the calculated Cultural Indices and Value Consistencies. An obvious limitation is the further reduction in the number of data values, from an already low original n=14, due to the exclusion of inconsistent responses.

Table 5: Test-retest reliabilities

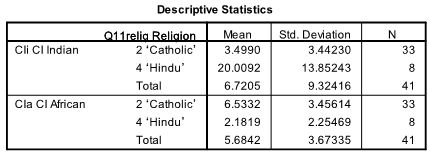

Stage 2 (b) Religion and strength of Ethnic Identity were used to assess the construct validity of the cultural identity measurements.

The mean ethnic cultural identities of Hindus and Catholics are given in Table 6.

Table 6: Ethnic cultural identities of Hindus and Catholics

Table 7 gives the MANOVA testing the differences in these mean levels of Indian-ness and African-ness of Hindu and Catholic respondents. It shows both differences are highly significant.

Table 7: Construct validity evidenced by significant differences between Indian-ness and African-ness of Hindu and Catholic respondents

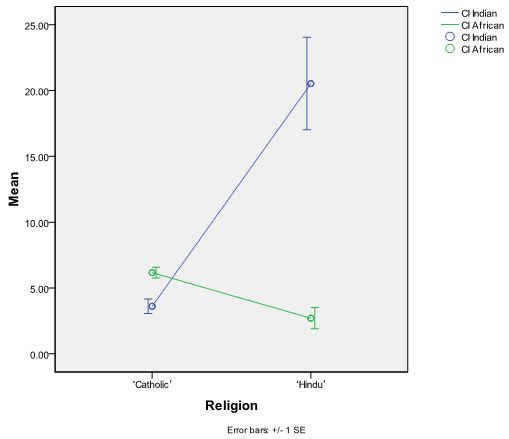

Figure 2 is based on Table 6 and shows the mean African-ness and Indian-ness of Hindus and Catholics with one standard deviation error bars to illustrate their separations. The effect sizes of these F values are large and medium respectively (Cohen, 1988).

Figure 2: Effect sizes of differences between Indian-ness and African-ness of Hindu and Catholic respondents

These expected results strongly support the construct validity of our Cultural Index measures.

Stage 3: Year-by-year changes in students’ French and Spanish cultural identity components

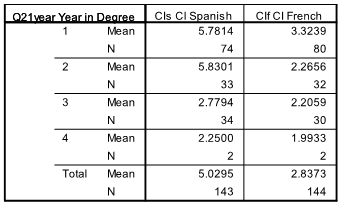

Table 8 shows student numbers and students’ mean Spanish-ness and French-ness cross-sectionally at each year of the language programmes.

Table 8: Mean French and Spanish Language Identities at each year of the programme

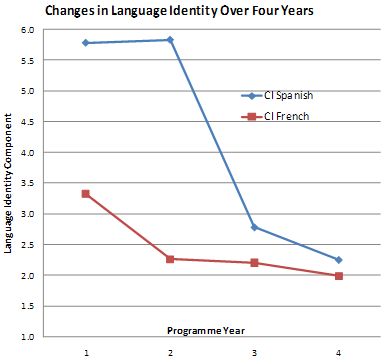

The means from table 8 are plotted in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Changes in students’ French and Spanish Language Identities over four years of teaching

Figure 3 shows that the Language Identity of students decreases over the four years of the language programmes. For French, there is a marked decrease by the end of year two. However, The Spanish Cultural Index is still high at the end of year 2 and then plummets by the end of year 3. Both components of language identity reach their lowest level at the end of year 4.

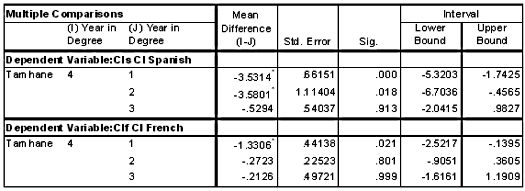

Post-hoc Tamhane T2 multiple comparison tests, for unequal n and variances, between the means for each year, as given in Table 9, show that for Spanish the drop of from year 1 to year 4 was highly significant (p<0.001, actually p=0.000006) and was significant for French at p<0.05, actually p= 0.021)

Table 9: Significant decreases in students’ Language Identities by the end of the programme

Stage 4: Meanings of French and Spanish cultural identity components

Figure 4 shows the two-dimensional ranking of respondents on their Language Identities and the High-Low extreme respondents. Three ‘high Spanish low French’ and 3 ‘high French low Spanish’ have been marked.

Figure 4: Selection of students who have maximally contrasting Language Identities for explorative interviews

Table 10 lists the high and low French and Spanish language identities of these six students selected for interview

Table 10: High and low French and Spanish language identities of six students selected for interview

As this is a work-in-progress only students F1 and F2 have so far been interviewed. From these interviews it seems that language Identity is composed of two characters: (i) a perceived self-competence, e.g. resulting from relative skill level and (ii) a cultural component, e.g. resulting from family background. The students are aware of differences in the French and Spanish values that are directly and indirectly taught but they do not seem to have imbued them.

Future interviews will need to explore the meanings of the 2nd and 3rd year decreases in Language Identity by interviewing students identified as having a large year-on-year language Identity decrease.

Student enculturation comprises two attainments; skills and values. Formal teaching and objective assessment methods for the detailed articulated skills content of our courses are designed to raise the skill attainments of our students. In contrast, the informal teaching and non-assessment of subjectively defined values content often fails to ensure our students attain the commensurate values for enculturation. We are thus in danger of passing students with skills honed for no-purpose, or worse, skills attuned to unknown or unethical intent. This is of high public concern in high profile, high outcome-risk vocations such as medical sciences, engendering attempts at assessing professionalism to avoid producing more Menglers of medicine (Grodin & Annas, 2007; Knopp, 2006). It is of high educational concern in other subject areas, and with the EU Galanet project interventions is now becoming both an educational and public concern in the teaching of foreign languages where imbuing the target language culture is both major motivation for foreign language study and a valued outcome of foreign language study.

We have proposed that in prevalent assessment-driven learning environments the availability and use of objective skills assessments favour skills attainment, whereas the lack of objective values assessments, and the consequential non-assessment of values, undermines values attainment. With the aim of countering values deficiency while maintaining traditional levels of skills attainment, this paper has presented an objective method of monitoring attainment of subject cultural identity during the enculturation process of learning. In particular it has demonstrated an objective method of monitoring attainments of language identity over the course of foreign language learning; a simple method that teachers of languages can use to ensure their own efforts of enculturating their students into the culture of their target language are being successful.

Students (N=231) of French and/or Spanish in years 1 to 4 of their university programme were respondents in this research. The Culturometric objective monitoring of French and Spanish language identity, as demonstrated in this paper, used the Cultural Index (CI) Regulator in order that these respondents’ subjective self-ratings of their language identities could be objectively compared by grounding in their consensus of meaning of these language identities. The agreement of rules-of-thumb with formal decision criteria was demonstrated for choosing the most appropriate public objects to use for consensus grounding. The Value Consistency method of identifying inconsistent responders was also demonstrated and validated by showing before/after gains of 50% in C-alpha reliabilities against losses of only 35% in data exclusions. The CI Regulator methodology was also validated by two expected findings of significant differences between the Indian and African identities of Hindus and of Catholics; vis. that Hindus were significantly more Indian and Catholics are significant more African, as expected in Trinidad and other Africian/Indian Diaspora (Mackintosh, 2005).

Cross-sectional comparisons of French and Spanish Language Identities over the four years of the language programmes showed the unexpected result of significant reductions in both French and Spanish language identities between the first year and last years of the programme, with the largest drops for French after year one and for Spanish after year two. This result was surprising as lecturers had many informal procedures in place aimed at increasing language identity with successive years of the programme.

As this is an on-going programme, students with contrasting high vs. low language identities have been identified for exploratory interviewing to help specify the consensus meanings of French and of Spanish Language identities. Other students have been identified for interviews to discover and counteract causes of the decreases in language identities observed over the years of the programme. Preliminary results point to two aspects of language identity (i) a skills-based perceived relative self-competence and (ii) a family based cultural modelling. It is tentatively hypothesised from the interviews so far conducted that an initially high perceived competence of year 1 students is inherited from students’ previous in-school performances and confirmed by acceptance on their University programmes. However, highly demanding competence assessments in first-year French and in Second-year Spanish demolish this component of language identity and the less common cultural component is maintained only in students with continuing external support in the cultures of the target languages.

The fact that students can pass courses on skills attainment alone is a lesson of the ‘hidden curriculum’ that students learn increasingly well over the length of their programmes. The Culturometric method of monitoring subject identity, as demonstrated in this paper, offers a simple on-going assessment of values attainment. These measurements can be used (i) for on-going course planning, e.g. to identify high vs. low attainers for interviews to delineate students’ meanings of subject identity for corrective teaching of values, and (ii) for alerting educators to the relative successes of their methods of enculturating students into the values of their subjects.

Anderson, M.W. (2007). Assessment matters - Should improving student thinking include altering student values? The role of general education. About Campus, 12(3),23-25

Andrade, A., Araújo e Sá, M.H., Lopéz Alonso, C., Melo, S. & Séré, A. (2005) Galanet: Manual do Utilizador. Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro.

www.galanet.eu/publication/fichiers/manuel.pdf (accessed 16th May 2009).

Araújo E Sá, M.H. & Melo, S. (2007). Online Romance Languages Cross-comprehension in the Development of Educational Competence: A study of future teachers’ perceptions. E–Learning,, 4(1), 52-63.

Aspin, D.N. & Chapman, J.D. (2007). Values Education and Lifelong Learning: Principles, Policies, Programmes. Dordrecht: Springer.

Beauchamp, G. (2004).The challenge of teaching professionalism. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 33(6), 697-705.

Boxer, D. & Cortés-Conde, F. (2000). Identity and ideology: Culture and pragmatics in content-based ESL. In J.K. Hall and V.L. Stoops (Eds.) Second and Foreign Language Learning through Classroom Interaction (pp. 203-219). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers,.

Brown, S., Birch, D., Thyagaraj, S., Teufel, J., & Phillips, C. (2007). Effects of a single-lesson tobacco prevention curriculum on knowledge, skill identification and smoking intention. Journal of Drug Education, 37(1), 55-69.

Bruna, K. R. (2009). Materializing multiculturalism: deconstruction and cumulation in teaching language, culture, and (non) Identity reflections on Roth and Kellogg. Mind, Culture and Activity, 16(2), 183-190.

Byram, M. & Feng, A. (2005). Culture and language learning: teaching, research and scholarship. Language Teaching; 37(3), 149-168.

Clark, J.K., Sauter, M., & Kotecki, J.E. (2000). Adolescent girls' knowledge of and attitudes toward breast self-examination: Evaluating an outreach program. Journal of Cancer Education, 15(4), 228-231.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Crossley,J., Davies, H., Humphris, G. & Jolly, B. (2002). Generalisability: A key to unlock professional assessment. Medical Education, 36(10), 972-978.

Cruess, R.L. & Sylvia R Cruess, S.R. (2006). Teaching professionalism: General principles. Medical Teacher, 28(3), 205-208.

Cruess, R.L. (2006). Teaching professionalism: Theory, principles, and practices. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 449, 177-185.

Dlaska, A.(2000). Integrating culture and language learning in institution-wide language programmes. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 13(3),247-263.

Donaldson, R.P., & Kotter, M. (1999). Language learning in cyberspace: teleporting the classroom into the target culture. CALICO Journal,16(4), 531-557.

Fayolle, A., & Degeorge, J.M. (2006). Attitudes, intentions and behaviour: New approaches to evaluating entrepreneurship education. In A. Fayolle and H. Klandt (Eds.) International Entrepreneurship Education (pp. 74-89). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Fryer-Edwards, K., & Baernstein, A. (2004). Where the rubber meets the road: A Cyclist's guide to teaching professionalism. The American Journal of Bioethics, 4(2), 22-24.

Genc, B., & Bada, E. (2005). Culture in language learning and teaching. Reading Matrix: An International Online Journal, 5(1), 73-84.

Ginsberg, S., & Stern, D. (2004). The professionalism movement: Behaviors are the key to progress. The American Journal of Bioethics, 4(2), 14-15.

Grodin, M., & Annas, G. (2007). Physicians and torture: lessons from the Nazi doctors. International Review of the Red Cross, 89, 635-654.

Kane, M.T. (1992). The Assessment of professional competence. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 15(2), 163-182.

Ke, L.S. (2008). Effects of educational intervention on nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions toward supplying artificial nutrition and hydration to terminal cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 16(11), 1265-1272,

Kelleher, J. (2003). Professional development that works: A Model for assessment-driven professional development. Phi Delta Kappan, 84, 751-757.

Kjaerbeck, S. (2005). Narratives in talk-in-interaction: Organization and construction of cultural identities. Construction of sociocultural identities in face-to-face interaction. In B. Preisler, A. Fabricius, H. Haberland, S. Kjaerbeck, K. Risager (Eds), The Consequences of Mobility: Linguistic and Sociocultural Contact Zones (pp. 45-57). Roskilde: Department of Language & Identity, Roskilde University.

Knopp, R. (2006). The challenges of teaching professionalism. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 48(5), 538-539.

Lemke, J. (2002). Becoming the village: Education across lives. In G. Wells, & G. Claxton (Eds) Learning for Life in the 21st Century (pp 34-45). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Liddicoat, A. (2005). Culture for language learning in Australian language in education policy. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 28-43.

Lin, A.M.Y. (Ed).(2008). Problematizing Identity : Everyday Struggles in Language, Culture, and Education. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Lindemann, J., & Soule, D. (2006). Teaching professionalism to medical students: A faculty guide. Journal of the South Dakota State Medical Association , 59(5), 203-205.

Lovat, T., & Toomey, R. (Eds.) (2009). Values Education and Quality Teaching: The Double Helix Effect. New York: Springer

MacDonald, M.N.,Badger, R., & Dasli, M. (2006). Authenticity, culture and language learning. Language and Intercultural Communication, 6(3&4), 250-261.

Mackintosh, M. (February 2005). DMAG Briefing 2005/6. London - the world in a city: An analysis of 2001 Census results. London: Data Management and Analysis Group, Greater London Authority.

Maine, S., Shute, R., & Martin, G. (2001). Educating parents about youth suicide: Knowledge, response to suicidal statements, attitudes and intention to help. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 31(3), 320-332.

Met, M. & Byram, M. (1999). Standards for foreign language learning and the teaching of culture. Language Learning Journal, 19(1), 61-68.

Minami, M. (2004). Culture as the core: Perspectives on culture in second language learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26(4), 629-630.

Ogletree, R.J., Hammig, B., Drolet, J.C., & Birch, D.A. (2004). Knowledge and intentions of ninth-grade girls after a breast self-examination program. Journal of School Health, 74(9), 365-369.

Paige, R. M., Jorstad, J., Siaya, L., Klein, F., & Colby, J. (2003). Culture learning in language education: A review of the literature. In D. Lange, & R. M. Paige (Eds.), Culture as the Core: Integrating Culture into the Language Education (pp. 173-236). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Phillipson, R. (2002). English-only Europe? Language Policy Challenges. London: Routledge.

Preisler, B., Fabricius, A., Haberland, H., Kjaerbeck, S., & Risager, K. (Eds) (2005). The Consequences of Mobility: Linguistic and Sociocultural Contact Zones. Roskilde: Department of Language & Identity, Roskilde University.

Riley, P. (2007). Language, Culture and Identity: An Ethnolinguistic Perspective. London: Continuum.

Rowan, S. (2001). Delving deeper: Teaching culture as an integral element of second-language learning. Clearing House, 74(5), 238-241.

Roxas, B.G., Cayoca-Panizales, R., & de Jesus, R.M. (2008). Entrepreneurial knowledge and its effects on entrepreneurial intentions: Development of a conceptual framework. Asia-Pacific Social Science Review, 8(2), 61-77.

Royal College of Physicians of London (2005). Doctors in Society: Medical Professionalism in a Changing World. London, Royal College of Physicians of London.

Sambell, K., & Mcdowell, L. (1998). The construction of the hidden curriculum: Messages and meanings in the assessment of student learning. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 23(4), 391-401.

Sapir, E. (1921, 2005). Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech. Kessinger Publishing. (Chapter 10. Language, Race and Culture, also www.bartleby.com/186/10.html retrieved 16th May 2009.

Saultz, J.W. (2007). Are we serious about teaching professionalism in medicine? Academic Medicine, 82(6), 574-577.

Schwartz, R., & Lederman, N.G. (2002). It's the nature of the beast: The influence of knowledge and intentions on learning and teaching nature of science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching; 39(3), 205-236.

Shah, N., Anderson, J., & Humphrey, H.J. (2008). Teaching professionalism: a tale of three schools. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 51(4), 535-46.

Shiels, K. (2001). A qualitative analysis of the factors influencing enculturation stress and second language acquisition in immigrant students. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 62(2-A), 431.

Slivenskya, S. (2008). The European centre for modern languages: Recent projects. Language Teaching, 41, 435-443.

Souitaris, V, Zerbinati, S, & Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of leaming, inspiration and resources. Journal of Business Venturing, 22, 566-591.

Stern, D.T. (Ed.) (2005) Measuring Medical Professionalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thomson, R.A. (2001). On teaching professionalism. Journal of Family & Consumer Sciences, 93(2), 18-18.

Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M. (1996). The assessment of professional competence: Developments, research and practical implications. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 1(1), 41-67.

Vez, J.M. (2002). Entroducing a European dimensión into EFL teacher education. CAUCE, Revista de Filología y su Didáctica, n'25, 2002 /págs. 147-162.

Wear, D., & Kuczewski, M. (2004). The professionalism movement: Can we pause? The American Journal of Bioethics, 4(2), 1-10.

Wenger. E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ytterberg, S.R., Plotnikoff, G.A., & Harris, I.B. (1998). Teaching professionalism through tutorial discussions of literature-stories, poems, and essays. Academic Medicine, 73(5), 575-6.

Please check the British Life, Language and Culture course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Train the Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|