The Use of Music in English Teaching in the Philippines

Kim F. Rockell and Merissa B. Ocampo, Japan

Kim Rockell is a Ph.D. graduate of University of Canterbury and presently an associate professor at Aizu University, Japan. He is a classical guitarist, ethnomusicologist and ESL educator. E-mail: kimusiknz@gmail.com

Merissa Braza Ocampo is a Ph.D. graduate of Hokkaido University, Japan and TESOL Diploma holder. At present, she teaches EFL at Fukushima Gakuen University, Japan.

E-mail: merissa@yahoo.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

English in the Philippines

Objective

Method

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

References

Appendix

Although the role of musical approaches within language education is becoming firmly established, few studies have considered music and language education in specific regional contexts. Building on a recent study conducted in Japan (Rockell & Ocampo, 2014), the authors present research on the use of music to teach English in the Philippines. Based on the responses of 37 teachers at high schools and tertiary institutions to a self-assessment questionnaire administered at the end of 2014, the study examines teachers’ appraisal of general musical skills and strategies, use of specific musical techniques and specific song repertoire used when teaching English. For readers less familiar with the English language situation in the Philippines, a brief historical summary is provided near the beginning of the paper. In addition to details of music use, the information provided by teachers offers insight into the professional activities of English teachers in the contemporary Philippines. Comparisons with the authors’ recent Japan-based study are also discussed in the text.

As we move into the first decades of the twenty-first century, serious scholarly work continues to examine the music/language nexus and research across a range of disciplines substantiates the importance of this relationship (Arbib, 2013; Mithen, 2005, p. 43; Patel, 2010). In the fields of First Language Acquisition (FLA) and Second Language Acquisition (SLA), music is increasingly viewed as a solid and effective teaching tool, which can genuinely help students towards attaining their language learning goals (Ajibade & Ndububa, 2008; Butto, Holsworth, Morikawa, Wakabayashi, & Edelmen, 2014; Engh, 2013; Guglielmino, 1986; Hashim & Abd Rahman, 2010; Hidayat, 2013; Karsenti, 1996; Kristin, 1996; Lems, 2001; Mashayekh & Hashemi, 2011; Medina, 1990; Mora, 2000; Rockell & Ocampo, 2014; Salcedo, 2010; Setia et al., 2012; Stansell; Wang, 2008). The current literature tends to emphasize the following positive results of music on language learning (Rockell, 2015, pp. 247-248):

- The amelioration of pronunciation and enhanced awareness of prosodic features of language such as rhythm, stress and intonation

- A positive impact on the affective dimension of classroom activity

- Greater sense of enjoyment and increased confidence

- Increased sociability engagement and participation

- Enhanced vocabulary recall

Recognition of the above benefits is prevalent within studies that tend to look at music and language without focusing on a specific location or cultural context. However, as interest in World Englishes and the way English education is nuanced in different parts of the world grows (Crystal, 2012; Graddol, 2003, 2004; Nunan, 2003; Tupas, 2008), and particularly in Asia (Bolton, 2008; McArthur, 2003; Smith, 1998; Tsui & Tollefson, 2007), how music’s place in language teaching varies from country to country also becomes increasingly important.

Following on from an earlier Japan-based study (Rockell & Ocampos, 2014), the current paper examines the way music is used by English language teachers in the Philippines, a country ripe with possibilities for linguistic investigation. The authors also share a particular interest in the Philippines, are both active musically and as English language educators, and have both previously published on Philippine health and arts related topics (Ocampo, 1997; Rockell 2013). These factors provided additional impetus for the current research. For those readers who are less familiar with the Philippines, and the English language situation in the archipelago in particular, the following historical summary may provide a helpful background to the current study.

With a current population of over one hundred million people, the Philippines boasts a significant number of English speakers within its society (Bautista & Bolton, 2008). Although historically multilingual (Gonzalez, 2008), with more than 100 indigenous Austronesian languages spoken throughout the Philippine archipelago (Bautista & Bolton, 2008), the English language now dominates important domains of societal control (Rafael, 2008) and has become particularly entrenched within the realm of education (Bernardo, 2008). Music and entertainment in English such as films from the United States also continue to exert a prominent influence (Rafael, 2008).

English was taught from the earliest days of American presence in the country, by American teachers, now known as Thomasites, who arrived at the end of the Philippine American war from 1901, and were dispersed throughout the islands (Bautista & Bolton, 2008). Local agency was also important in disseminating the language. By 1921, over 90% of English teachers were native-born Filipinos, passing on what they had learned from their American mentors (Bautista & Bolton, 2008). It has been suggested that a favorable disposition towards English that was suitable for learning the language existed in the Philippines at that time (Gonzalez, 2008). Other factors contributing to this propensity may have been due to a form of the Roman alphabet being present already as a result of earlier Spanish presence and to the pre-knowledge of lexical items from another European language by speakers of the major three languages (Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilocano). It also seems significant that radio broadcasting was introduced during this period, which would have helped promote a wider dissemination of the English language (Rosario-Braid & Tuazon, 1999). For some time, a steady stream of rich input in the form of movies, music and advertising etc. has been reaching Filipino ears.

In the wake of globalization and continued demand for English for international engagement and employment at home and abroad (Bautista & Bolton, 2008; Gonzalez, 2008), the role and status of English in relation to other languages in the Philippines is by no means a simple matter. In many, particularly informal contexts, code-switching with local languages is extremely common. Considering English alone, societal inequality, with a privileged elite speaking prestige dialects (Kroch, 1978) that tend to more closely approximate an American model (Tupas, 2008), a number of ‘edulects’ reflecting a speaker’s scholastic background and level of educational attainment (Gonzalez, 2008) and various permutations of what is now recognized as Philippine English, appears reflected and maintained through language.

Philippine English, as characterized by researchers, has a distinct accent, which appears to be more syllable-timed than stress-timed. It also has a reduced vowel inventory and is distinctive in terms of placement of stress on syllables (Gonzalez, 2008). Grammatical features such as tense-aspect and article system are sometimes restructured (Gonzalez, 2008), and the lexicon includes localized vocabulary and direct loan translations from Philippine languages (Bautista & Bolton, 2008). Work on Philippine English phonology (Alberca, 1978; Gonzales & Alberca, 1978; Gonzalez, 1997; Llamzon, 1969; Tayao, 2004), lexicon (Cruz & Bautista, 1993) and grammar restructuring (Bautista, 2000) contribute to our understanding of this vibrant World English variety.

For those preparing for work in Philippine-based Call Centers, which numbered 200,000 in 2006 (Bautista & Bolton, 2008), or the many foreigners who have recently begun choosing the Philippines as a destination in which to study English, or in English, however, the guiding aesthetic would still tend to be provided by Standard American English.

Since the Thomasites began a tradition of teaching English “analytically, via grammar, definitions of parts of speech, exemplification, and numerous exercises of what we would now call testing rather than teaching exercises” at the beginning of the 20th century (Gonzalez, 2008), English has retained a sturdy foothold within the Philippine educational system (Bernardo, 2008). However, there was no deliberate emphasis on American phonology in the early stages of teaching, which contributed to the development of local styles of pronunciation (Gonzalez, 2008). Aural/oral traditions such as epic poetry were important educational vehicles in the pre-European or pre-contact Philippines, and this may have initially influenced the oratorical style in which English is delivered in the country (Gonzalez, 2008).

The Philippine people are frequently characterized as highly musical, “singing” people (Manuel, 1980) so one might expect to find this musicality pervading language teaching and other educational processes. The question arises as to whether Filipinos’ self-identification as music lovers leads to an intensified sense of the value of music as an academic tool, or, in contrast, does the ubiquitous nature of music in the Philippines cause it to be considered external to scholastic/academic contexts and endeavors? Further, it is the case that the bilingual policy implemented in the Philippine education system beginning in the 1970s compartmentalized subjects by separating and equating certain domains of knowledge with certain languages. Math and science, for example, were to be taught in English, while Filipino was to be used when teaching other subjects such as arts (Bernardo, 2004). Such a system would not foster a natural connection between music and educational activity in English.

Outside the world of formal education, musical input in English, external to scholastic contexts, is widespread thanks to media and patterns of musical participation. Recordings of song texts in English, which retain their integrity and, as recordings, are resistant to code switching, continue to provide an aural impression of English to the Philippine public. The following examination of the use of music in English teaching in the Philippines is situated within the more general context of English in the Philippines, which has been briefly outlined above, for the benefit of readers unfamiliar with the circumstances in the country.

In conducting this study, we sought to gain insight into the use of musical skills to foster language learning in the present day Philippines, particularly amongst teachers working at high school and college level. Music is one possible pedagogical tool available to teachers in the Philippines and it invites curiosity as to whether the use of music is seen as core or peripheral, whether it is seen as a teaching strategy per se or if it is merely decorative or aesthetic in character. Following the mode of enquiry applied in the previous Japan-based project (Rockell & Ocampo, 2014), the study examines:

- Teachers’ general profiles

- The transfer of musical skills and qualities to the teaching of English in the Philippines

- A variety of specific musical techniques, and how effective these are considered to be by teachers of English in the Philippines

- How intonation and stress are taught using melodic and rhythmic approaches in the Philippines

- Specific song repertoire used to teach Engish in the Philippines

- Perceived attitudes towards musicians teaching English in the Philippines

Through the examination of the above areas, we intend to gain a broader perspective on the use of musical skills and techniques by teachers of English in the Philippines. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study of its kind, so a general sourcing of information, rather than a singular focus on one specific element seems justified. The study also seeks insight into the professional situation of these teachers, and provides the opportunity to consider variations between the Philippine-based teachers and respondents in the authors’ previous study of teachers in Japan. Increased knowledge about how teachers in different countries use music in their teaching can assist in expanding the base of tools and techniques available to teachers worldwide. As well as their value to music and language educators, the understandings gained from such enquiry are also of potential use to researchers in a variety of fields, such as musicology, ethnomusicology and cultural or area studies.

During 2014, a questionnaire designed by the authors was distributed in English, both manually and electronically, to English teachers working at high school and college level in the Philippines (see appendix one, pages 24-31). Of 100 teachers approached, 37 returned their responses, providing sufficient data for a pilot study. The self-assessment style questionnaire was very similar to one used in the Japan-based study (Rockell & Ocampo, 2014). The questionnaire was divided into three sections. Part One asked for general information including teachers’ age, teaching experience and educational attainment. Part Two asked teachers to appraise the application of a set of musical skills and qualities. They were also asked to rate the use of specific musical techniques when teaching English. Part Three asked for additional information, including teachers’ perception of the hiring process, ways to apply music in the English classroom and specific song repertoire used when teaching English. Also, conscious of the uniquely multilingual situation of the Philippines, additional questions about teachers’ individual language use were added. Most questions were multiple-choice, allowing respondents to select from a given range, but questions asking for specific information, such as song repertoire, and open-ended questions that allowed for more detailed or personal responses were also included.

Self-assessment is a very helpful approach to exploring teachers’ perspectives, feelings and perceptions about their professional activity because it unobtrusively encourages candid self-reflection and offers respondents sufficient time and privacy to consider their answers (Spector, 1994; Stone, Bachrach, Jobe, Kurtzman, & Cain, 1999). The possibility of completing the questionnaire electronically also helped to make participation a lot more convenient for teachers in more remote locations.

Bearing in mind that a different sized data sample might result in different relative values, the information our respondents provided offered valuable insight into the world of Philippine English teaching and the salient characteristics of current practitioners. To begin, we present information on aspects such as age, experience, educational attainment and patterns of language use reported by our participants in response to Part One and Part Three of our questionnaire (see appendix one). Two thirds of the respondents were female. Ages ranged from 21 to 45 and above. The most strongly represented age groups were the 21 to 25 years age range or those aged 45 and above. Although a large number of teachers fell into the age range of from 41 to 45, or older, few teachers could claim over a decade teaching experience, suggesting that English teaching was a professional activity that many started later in their careers. Teachers with qualifications specifically related to English or English teaching were most strongly represented. A number of respondents also held postgraduate qualifications such as Masters degrees or Doctorates.

Respondents’ language use showed the breadth typical in the Philippines, although the majority considered Tagalog to be their first language (L1). Two non-Filipino teachers currently active in the Philippines, a Canadian and an American, also took part in this study, and these were the only respondents to self identify as native speakers of English. In addition to English and Tagalog, numerous respondents reported fluency in Ilocano and Cebuano. Speakers of Bikol, Chavakano, Ilongo, Waray, Pampangeno and Pangasinense were also represented within the study. In terms of teachers’ reported patterns of private language use in their homes, the majority of teachers reported that they communicated in Taglish (a combination of Tagalog and English), or a combination of their own regional language and English. Two respondents reported an English-only home environment, and only three respondents reported a Tagalog-only environment. A small group of teachers also reported using a combination of English and foreign languages such as French and Japanese for communication in the home.

Respondents also provided information about characteristics of their student population and working conditions. The majority of teachers reported working with students who had a Philippine language as a mother tongue, but students from other language backgrounds, particularly Japanese speakers, were also reported within the student population. In terms of contact hours, most teachers were active below 15 hours per week, but schedules of 40 and more contact hours were also reported.

Musical profiles of Philippine-based English teachers

In response to questionnaire Part Three, question 10 (see appendix one), half of the Philippine-based teachers of English stated that they had no formal musical training or background. 15% self identified as musicians and reported having received musical training while 17% had not studied music as a major but had received additional musical training or some kind. In addition to musical training, one indicator of musical engagement and interest is informal participation in karaoke singing, a common pastime amongst Filipinos (Askins, 2007; Ong, 2009; Rockell, 2009). Many respondents in this study, however, reported little or no interest in karaoke in answer to questionnaire Part Three, question 14.

Despite the reported lack of strong musical ability or interest amongst the Philippine-based respondents in this study, some, particularly those with a musical background, held a favorable view of the perceived value of musicality in the language classroom. 35% of musicians reported that their employers knew about their musical background at the time of hiring, and 31% considered musicality to be a big factor in why they were hired (questionnaire Part Three, question 1). Only 20% of respondents disagreed with the idea that there is a perception of musicians as capable English teachers in the Philippines (questionnaire Part Three, question 3).

Teacher’ self-assessment of six musical skills or qualities

In approaching the concept of musicality, the authors employed a heuristically based list of six skills and qualities that aims to offer a sensitively nuanced and sufficiently broad measure, taking into account recent scholarly perspectives from musicology and music education (Rockell & Ocampo, 2014). These six areas examined were:

- A well-developed sense of rhythm: Musical activity, such as singing and playing a musical instrument, promotes the development of a strong rhythmic sense (Drake, Jones, & Baruch, 2000). This sense positively affects the ability to both perceive stress and accent in spoken language and to lead rhythm drills effectively.

- Sensitivity to pitch and intonation: Sensitivity to pitch and intonation patterns is promoted by musical activity (Bolduc, 2008), and musicians are able to “consider utterances purely melodically, keenly sensitive to the pitch fluctuation in spoken language” (Rockell & Ocampo, 2014). This sensitivity helps to enhance awareness of prosodic features of language such as, stress and intonation and contributes to the amelioration of pronunciation.

- Demonstrative in speech and gesture: Both instrumental and vocal musical performance requires demonstrative speech and gestures and clear enunciation (O'Dea, 2000; Vines, Wanderley, Krumhansl, Nuzzo, & Levitin, 2004). This behavior influences the way a teacher presents examples and gives classroom instruction when teaching English.

- Skillful in facilitating interaction: Particularly relevant when conducting group work, experience of the communication that takes place in various kinds of musical ensembles influences a teachers’ ability to play a directive role in a variety of active language activities (Boespflug, 1999; Seddon & Biasutti, 2009). This skill helps teachers to be more effective when coordinating communicative group activities.

- Pre-disposed to comprehend grammatical analysis: A strong analogy can be drawn between the performance and musical analysis of chord sequences, and the grammatical analysis of linguistic systems (Besson & Schön, 2001). This disposition may give musicians “a cognitive advantage when approaching grammatical analysis and a freshness of approach towards grammatical problems” (Rockell & Ocampo, 2014).

- Self-disciplined and independent: Musical training can engender self-discipline and independence as a result of regular individual practice and the commitment to participation in musical ensemble activity (Dai & Schader, 2001; Sloboda, Davidson, Howe, & Moore, 1996). This component of musicality impacts on language teachers’ ability to carry out preparation, assessment and evaluation.

The above areas were examined in this study by means of questions 1 – 6 of Part Two A of the questionnaire. Based on their responses, the musical profiles of teachers in this study showed a generally even distribution. It can be noted, however, that amongst this group of teachers, confidence was greatest with regard to social aspects of musicality, and least so when dealing directly with pitch and rhythm.

Philippine-based teachers’ responses to additional questions in questionnaire Part Three, questions 5 – 9, tended to emphasize the positive influence of musical experience and ability on their awareness of pronunciation and the underlying stress and rhythm in spoken language. In teaching, this awareness was most frequently applied to using chants. Some teachers stated that they did solfeggios (singing do, re, mi) in every class, which was considered to be a highly pleasurable activity. In addition, nearly half the participants considered that musical ability enhanced their general non-verbal communication skills

The direct and indirect use of musical skills and strategies to teach English in the Philippines

When asked whether they had used melody as a tool to improve students’ spoken intonation contours (questionnaire Part Three, question 8), most teachers reported that that had done so. In terms of improving syllable stress through rhythm drills (questionnaire Part Three, question 9), however, almost half the participants replied that they had not used such drills. Of those that employed rhythm drills, one standard technique reported was to mark syllable stress as musical notes above the stressed syllables in a written sentence pattern, and emphasize these by clapping hands. This practice indicates that the emphasis of this group of teachers in teaching English pronunciation tends to prioritize intonation contour to some degree over syllable stress.

The use of music in the classroom can be viewed as direct and indirect depending on how explicitly they are applied or how central they are to a particular language learning activity. In terms of direct use of musical skills, Philippine-based teachers emphasized listening to music with the goal of enhancing students’ receptive and productive capacity (questionnaire Part Three, question 7). Improving students’ memory was the most frequently cited indirect use of music in the Philippine English language classroom (questionnaire Part Three, question 6). Stress reduction and encouraging students to relax were also prominent.

Use of specific musical techniques in the classroom

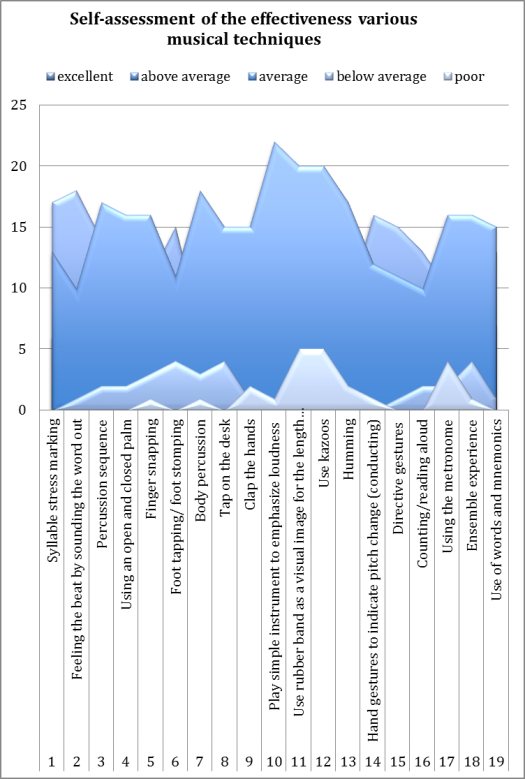

To learn how teachers in the Philippines applied specific musical techniques, a list of simple melodic and rhythmic devices was presented to participants. This list was the same as that given to teachers in the authors’ Japan-based study (Rockell & Ocampo, 2014). These questions are found in Part Two B, questions 1–19 of the questionnaire used in the current study. Results are shown in figure 1, which indicates graphically the relative degree to which teachers appraised their efficacy in the use of the various techniques. The diagram indicates that overall, the most positively appraised techniques, based on a positive rating of excellent or above average were:

- Feeling the beat by sounding the word out (syllable stress/accent)

- Hand gestures to indicate pitch change (intonation/melody)

- Syllable stress marking (syllable stress/accent)

- Directive gestures (ensemble)

The confident appraisal given here to techniques relating to syllable stress balances the earlier finding that English teachers in the Philippines are using rhythm drills less. Based on a poor or below average rating, the least positively appraised techniques by the teachers in this study were the use of idiophones and musical devices such as the metronome, kazoos and rubber bands. Given that, in general, this group of respondents did not claim strong musical interest or ability, it is understandable that they would not have idiophones or other musical devices readily at hand while teaching.

Figure 1. Self-assessment of the effectiveness various musical techniques in teaching English in the Philippines

Song repertoire

An extra aspect incorporated into the current study, which had not been part of the authors’ earlier examination of the music and English teaching in Japan, was the question of specific song repertoire (questionnaire Part Three, question 13). The titles of these songs are listed in figures 2 and 3. Amongst these, most popular were “Head shoulders knees and toes” and the “The alphabet song”, emphasizing physically mediated musicality (Rockell, 2009) and a focus on literacy, respectively. Based on the authors’ individual experiences teaching English in Japan to young learners in a variety of situations for more than a decade, it can be said that the majority of these songs are used in both the Philippines and Japan. Exceptions are songs such as “Noah’s ark” and “Seven things to praise about the Lord”, which seem specific to the Philippines, reflecting the generally more prevalent religiosity within Philippine society.

Respondents also listed a number of songs in English that originate in the Philippines. It is often difficult to clearly identify the composers and lyricists of popular Filipino songs, which tend to be identified more strongly with their performers.

Of those reported, the most frequently mentioned was Gary Valenciano’s ballad “Take me out of the dark”. This is listed below with other songs, all of which can be classified as romantic ballads more appropriate for older learners, including those seen in figure 2.

Figure 2. Filipino songs in English used to teach English in the Philippines

Figure 3. English songs used by English teachers in the Philippines

This study revealed a great variety in the profiles and practice of Philippine-based English teachers. Respondents’ feedback affirmed the idea of a multi-lingual breadth in the everyday language use of these Philippine-based English teachers. This situation contrasts interestingly with Japan. In the Philippines, where English shares an official language status with Filipino, local instructors have been disseminating a version of standard American English for over a century, although they do not self-identify as native speakers. In Japan, however, where English is a foreign language and is used for international communication but is not considered to be a national language, a climate of ‘native speakerism’, privileges non-Japanese native speakers (NS) working with texts from either British or American sources. Students of English in Japan tend to be Japanese speakers in the main, whereas the Philippines has also become a destination for non-Filipinos from outside the Philippine to come to learn English, so there is more variety within the student base being served by these teachers and consequently a more varied intercultural dynamic at play.

The majority Philippine-based teachers in this study, as well as NS and non-native speakers (NNS) in Japan, believed that music and musical ability were useful and valued on the part of educational employers. However, despite the use of music in English teaching being substantiated in the academic literature, skill transfer from music and its actual use on an individual level did not appear to be as strong amongst Philippine teachers in this study, certainly when compared to the NS group in Japan. Japan-based respondents also claimed to have met many more musicians teaching English than those respondents in the Philippines study. This more peripheral status contradicted the expectation that Filipinos, frequently characterized as highly musical (Manuel, 1980), would use music a great deal in education. The compartmentalization of subjects according to language under bilingual education was suggested earlier as a possible explanation for this finding but this was not confirmed in the current research. Certainly, the value of the kind of creative thinking associated with music and arts in enhancing educational processes was noted by participants in the earlier Japan study, but did not appear as a significant idea within the Philippine group.

As mentioned earlier, English teachers in the Philippines appraised their musical skill and qualities evenly across each category, but appeared less confident working with pitch and rhythm directly, aspects appraised strongly by the NS group in the earlier Japan-based study. However, as mentioned earlier, listening to music was considered to have a positive impact on both students receptive and productive ability in English. This view was also widespread amongst the Japan based teachers.

The Philippine teachers’ affirmation of a meaningful relationship between musical pitch and intonation and rhythm with stress in spoken language, while not applying these ideas personally, may point to a disjuncture between their stated attitude/position and appraisal of their individual personal practice or the limits placed on them by their workplace. Half of the respondents in the Japan-based study used melody to improve intonation contours in spoken English, but NNS teachers to a much lesser extent.

Unlike respondents in the earlier Japan-based study, of whom very few claimed to use music directly as a motivational tool, some Philippine-based teachers did use music in this way. Also, while more than half of teachers in the Japan study used music as a way to “switch on the English brain before class”, the regular presence of English songs on radio and television in the Philippines, as well as singing as part of the celebration of Christmas and other holidays from the Christian calendar may make this deliberate use of music less necessary in the Philippine context. Differences in societal expectations and environmental ambience between the Philippines and Japan impacted directly on the application of musical techniques in the classroom. For example, the tendency towards reticence and passive observation on the part of Japanese students, the idea or “shyness” (Doyon, 2000; Hinenoya & Gatbonton, 2000; Matsumoto, 1994), which might influence students to be less willing to clap their hands (Rockell & Ocampo, 2014) contrasts with ethnographic observations of the lively Philippine interactive character (Rockell, 2009). However, during more than a decade’s residence in Japan, the authors have frequently observed Japanese audience members clapping rhythmically, albeit in synchronized or regularly choreographed manner, at a variety of musical and sporting events, so it may be the case that clapping is a situation specific behavior thought inappropriate, or at least unfamiliar in a language learning context, especially for adult learners.

The power of music to induce relaxation was also highlighted by Philippine-based teachers. Both Philippine-based teachers and NS teacher in the Japan studied were less confident about using simple idiophones or gadgets in the classroom than were NSS teachers in Japan, although perhaps for different reasons. NSS teachers’ contrasting acumen in using such gadgets may be result of the increasing prevalence of mobile communication devices, and automatized services such as vending machines in contemporary Japanese society.

In terms of song repertoire used to teach English it was interesting to note that, with the exception of certain religious songs, the same songs were being used to teach English to young learners in the Philippines as in Japan. However, in Japan a body of creative work aimed at young language learners, such as the jazz chants of Graham are available (Graham, 1978, 1996, 2002). The Philippines, in contrast, has a repertoire of authentic Filipino songs in English, which are available to be used as materials for language learners. Given that the majority of respondents in the current study were active at a High School and tertiary level, it is curious that songs generally aimed at young learners were most strongly represented. This warrants further investigation, as does the question of how teachers at kindergarten and primary level are using music and song to support language learning. Also, while compiling repertoire list is an important first step, it would be helpful to know in detail how this material is being used. In what ways, if at all, are the lyrics manipulating for educational purposes? What is the role of instrumental accompaniment when songs are used to teach language in the Philippines? A more detailed focus on the use of music in language teaching in the Philippines needs to consider these questions.

This study identified general trends and tendencies and revealed great variety in the profiles and practice of Philippine-based English teachers at high schools and tertiary institutions. It also provided an insight into song repertoire, demonstrating that original, Filipino songs in English are being used as vehicles for language teaching in the contemporary Philippines. At the same time, the use of music to teach English amongst the respondents of this study was not as extensive as anticipated, suggesting that the ubiquitous nature of music in the Philippines causes it to be considered external to scholastic/academic contexts and endeavors. These teachers recognized the potential value of music, and considered that musical ability may be attractive to employers of English language teachers, but they did not individually claim a strong musical orientation. English teachers in the Philippines, like their counterparts in Japan, could also benefit from becoming “more aware to the educational potential of music” (Rockell & Ocampo, 2014).

The authors urge other researchers to build on their work by conducting further studies on music in language teaching in the Philippines and other neighboring countries. While the authors’ current work is a helpful exploratory first step, issues arising from this paper can springboard more finely focused, ongoing investigation. As suggested, it is important to discover what teachers who work with younger learners exclusively are doing.

In terms of expanding our understanding of music and language learning in general, a comparative perspective, which takes in to consideration how students engage musically in other part of the world, would be a very fruitful avenue for future research (Rockell & Ocampo, 2014). The way these processes are nuanced from country to country offers valuable insights into the music/language nexus. Further, in some parts of the world, music is suppressed and yet it appears that members of those societies still want to learn English. It may be helpful to discover whether a lack of musical input impacts on their English learning outcomes.

In the near future the authors intend to extend their investigation of music in English teaching in the Philippines to Taiwan. In addition to the kind of emic perspectives shared by teachers through questionnaires in this study, it is hoped that future work will incorporate an expanded research design including case studies and direct classroom observations of music applied to language learning. In this way, a more solid contribution can be made to our understanding of how music is applied to the teaching of language indifferent parts of the world and in specific regional contexts.

Ajibade, Y., & Ndububa, K. (2008). Effects of word games, culturally relevant songs, and stories on students' motivation in a Nigerian English language class. TESL Canada Journal, 26(1), 27-48.

Alberca, W. L. (1978). The distinctive features of Philippine English in the mass media. (PhD), University of Santo Tomas, Manila.

Arbib, M. A. (2013). Language, Music, and the Brain: A Mysterious Relationship: MIT Press.

Askins, M. (2007). Zhou Xun and Francesca Tarocco: Karaoke: The Global Phenomenon [Review of the book Karaoke: The Global Phenomenon, by X. Zhou and F. Tarocco]. International Journal of Communication, 1(1), 3.

Bautista, M. L. S. (2000). Defining Standard Philippine English: Its Status and Grammatical Features. Philippine journal of linguistics.

Bautista, M. L. S., & Bolton, K. (Eds.). (2008). Philippine English Linguistic and Literary Perspectives: Hong Kong University Press.

Bernardo, A. B. I. (2004). McKinley's questionable bequest: Over 100 years of English in Philippine education. World Englishes, 23(1), 17-31.

Bernardo, A. B. I. (2008). English in Philippine education: Solution or problem? In M. L. S. Bautista & K. Bolton (Eds.), Philippine English Linguistic and Literary Perspectives. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Besson, M., & Schön, D. (2001). Comparison between language and music. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 930(1), 232-258.

Boespflug, G. (1999). Popular music and the instrumental ensemble. Music Educators Journal, 33-37.

Bolduc, J. (2008). The Effects of Music Instruction on Emergent Literacy Capacities among Preschool Children: A Literature Review. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 10(1), n1.

Bolton, K. (2008). English in Asia, Asian Englishes, and the issue of proficiency. English Today, 24(02), 3-12.

Butto, L. I., Holsworth, M., Morikawa, F., Wakabayashi, S., & Edelmen, C. (2014). Music: A motivator for underachieving EFL students? A Preliminary Study Using Karaoke. The Journal of the College of Foreign Languages Himeji Dokkyo University, 27, 49-54.

Cruz, I. R., & Bautista, M. L. S. (1993). A Dictionary of Philippine English. Pasig City: Anvil.

Crystal, D. (2012). English as a global language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dai, D. Y., & Schader, R. (2001). Parents' reasons and motivations for supporting their child's music training. Roeper Review, 24(1), 23-26.

Doyon, P. (2000). Shyness in the Japanese EFL class. LANGUAGE TEACHER-KYOTO-JALT-, 24(1), 11-16.

Drake, C., Jones, M. R., & Baruch, C. (2000). The development of rhythmic attending in auditory sequences: attunement, referent period, focal attending. Cognition, 77(3), 251-288.

Engh, D. (2013). Why Use Music in English Language Learning? A Survery of the Literature. English Language Teaching, 6(2).

Gonzales, A., & Alberca, W. L. (1978). Philippine English of the Mass Media, preliminary edition. Manila: De La Salle University Research Council.

Gonzalez, A. (1997). Philippine English: A variety in search of legitimation. In E. W. Schneider (Ed.), Englishes around the World, vol. 2: Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Australasia. Studies in Honour of Manfred Gorlach (Vol. 2, pp. 205-212). Amsterdam/Phiadelphia: John Benjamins.

Gonzalez, A. (2008). A favorable climate and soil: A transplanted language and literature. In M. L. S. Bautista & K. Bolton (Eds.), Philippine English Linguistic and Literary Perspectives (pp. 13-27). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Graddol, D. (2003). The decline of the native speaker. Translation today: trends and perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 152-167.

Graddol, D. (2004). The future of language. Science, 303(5662), 1329-1331.

Graham, C. (1978). Jazz chants. New York: Oxford University Press.

Graham, C. (1996). Singing, Chanting, Telling Tales: Arts in the Language Classroom. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Graham, C. (2002). Children's Jazz Chants: Old and New. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Guglielmino, L. M. (1986). The Affective Edge: Using Songs and Music in ESL Instruction. Adult literacy and basic education, 10(1), 19-26.

Hashim, A., & Abd Rahman, S. (2010). Using Songs To Reinforce The Learning Of Subject-Verb Agreement. Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia.

Hidayat, A. (2013). The Use of Songs in Teaching Students' Listening Ability. Journal of English and Education, 1(1), 21-29.

Hinenoya, K., & Gatbonton, E. (2000). Ethnocentrism, cultural traits, beliefs, and English proficiency: A Japanese sample. The Modern Language Journal, 84(2), 225-240.

Karsenti, T. P. (1996). Bringing songs to the second-language classroom. American Speech, 67, 339-366.

Kristin, L. (1996). For a Song: Music across the ESL Curriculum.

Kroch, A. S. (1978). Toward a theory of social dialect variation. Language in society, 7(01), 17-36.

Lems, K. (2001). Using music in the adult ESL classroom: National Clearinghouse for ESL Literacy Education.

Llamzon, T. A. (1969). Standard Filipino English. Manila: Ateneo University Press.

Manuel, E. A. (1980). The Epic in Philippine Litrature. Philippine Social Sciences and Humanities Review, 44(1-4), 328.

Mashayekh, M., & Hashemi, M. (2011). The Impact/s of Music on Language Learners’ Performance. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 2186-2190.

Matsumoto, K. (1994). English instruction problems in Japanese schools and higher education. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 5(4), 209-214.

McArthur, T. (2003). English as an Asian language. English Today, 19(2), 19-22.

Medina, S. L. (1990). The Effects of Music upon Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition.

Mithen, S. J. (2005). The singing Neanderthals: The origins of music, language, mind, and body. Cambridge, Masachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Mora, C. F. (2000). Foreign language acquisition and melody singing. ELT journal, 54(2), 146-152.

Nunan, D. (2003). The Impact of English as a Global Language on Educational Policies and Practices in the Asia‐Pacific Region. Tesol Quarterly, 37(4), 589-613.

O'Dea, J. (2000). Virtue or virtuosity?: explorations in the ethics of musical performance.

Ong, J. C. (2009). Watching the Nation, Singing the Nation: London‐Based Filipino Migrants' Identity Constructions in News and Karaoke Practices. Communication, Culture & Critique, 2(2), 160-181.

Patel, A. D. (2010). Music, language, and the brain. New York: Oxford university press.

Rafael, V. L. (2008). Taglish, or the phantom power of the lingua franca. In M. L. S. Bautista & K. Bolton (Eds.), Philippine English Linguistic and Literary Perspectives (pp. 101-127). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Rockell, K. (2009). 'Fiesta', Affirming Cultural Identity in a Changing Society: A Study of Filipino Music in Christchurch, 2008.

Rockell, K. (2013). The Philippine Rondalla: A Gift of Musical Heritage in a Migrant Context. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, 9(1), 97-120.

Rockell, K. (2015). Musical looping of lexical chunks: An exploratory study. JALT CALL Journal, 11(3).

Rockell, K., & Ocampo, M. (2014). Musicians in the language classroom: The Transference of Musical Skills to Teach "Speech Mode of Communication". ELTED, 16(Spring), 34-37.

Rosario-Braid, F., & Tuazon, R. R. (1999). Communication Media in the Philippines: 1521-1986 Philippine Studies (Vol. 47, pp. 291-318). Ateneo de Manila.

Salcedo, C. S. (2010). The effects of songs in the foreign language classroom on text recall, delayed text recall and involuntary mental rehearsal. Journal of College Teaching & Learning (TLC), 7(6).

Seddon, F., & Biasutti, M. (2009). A comparison of modes of communication between members of a string quartet and a jazz sextet. Psychology of Music, 37(4), 395-415.

Setia, R., Rahim, R. A., Nair, G. K. S., Husin, N., Sabapathy, E., Mohamad, R., . . . Jalil, N. A. A. (2012). English Songs as Means of Aiding Students’ Proficiency Development. Asian Social Science, 8(7), p270.

Sloboda, J. A., Davidson, J. W., Howe, M. J. A., & Moore, D. G. (1996). The role of practice in the development of performing musicians. British journal of psychology, 87(2), 287-310.

Smith, L. E. (1998). English is an Asian language. Asian Englishes, 1(1), 172-174.

Spector, P. E. (1994). Using self-report questionnaires in OB research: A comment on the use of a controversial method. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(5), 385-392.

Stansell, J. W. The Use of Music for Learning Languages: A Review of the Literature Jon Weatherford Stansell University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Updated September 14, 2005.

Stone, A. A., Bachrach, C. A., Jobe, J. B., Kurtzman, H. S., & Cain, V. S. (1999). The science of self-report: Implications for research and practice. New York: Psychology Press.

Tayao, M. L. G. (2004). The evolving study of Philippine English phonology. Special issue on 'Philippine English: Tensions and transitions'. World Englishes, 23(1), 77-90.

Tsui, A. B. M., & Tollefson, J. W. (2007). Language policy, culture, and identity in Asian contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Tupas, F. R. F. (2008). World Englishes of worlds of English? Pitfalls of a postcolonial discourse in Philippine English. In M. L. S. Bautista & K. Bolton (Eds.), Philippine English Linguistic and Literary Perspectives. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Vines, B. W., Wanderley, M. M., Krumhansl, C. L., Nuzzo, R. L., & Levitin, D. J. (2004). Performance gestures of musicians: What structural and emotional information do they convey? Gesture-based communication in human-computer interaction (pp. 468-478): Springer.

Wang, B. (2008). Application of popular English songs in EFL classroom teaching. Humanising Language Teaching, (3).

Language teaching in the Philippines: Probing the use of music in the language classroom

This questionnaire was created to evaluate and explore the use of music in the teaching of language. Please thoughtfully consider your responses to the following questions, and answer as honestly as possible. All efforts will be taken to ensure your anonymity. If you have any questions, please feel free to contact the researchers.

Part One. General Information

Please circle, underline or highlight your answer.

1. Age

- -25

- 26-30

- 31-35

- 36-40

- 41-45

- 45 and above

2. Gender

- Male

- Female

3. Educational attainment

- B.S. graduate with English Major, TESOL Diploma

- B.S. Graduate with other field except English related field

- M.A./M.S.

- Ph.D.

4. Length of teaching experience as an English teacher

- Less than one year

- 1-4 years

- 5-8 years

- 9-12 years

- 13-16 years

- 17-20 years

- More than 20 years

5. How many hours do you teach English in a week?

- 15 hours and below

- 16-20 hours

- 21-25 hours

- 26-30 hours

- 31-40 hours

- 41-45 hours

- More than 46 hours

6. When teaching English, which do you consider yourself to be?

- Native English teacher

- Non-native English teacher

- Other (please explain)

Part Two. Self-assessment about your general musical skills and qualities

Think about your musical ability and your effectiveness in using music to teach. Please check your answer according to the degree of effectiveness.

A. SELF ASSESSMENT OF YOUR GENERAL MUSICAL SKILLS AND QUALITIES

- A well-developed sense of rhythm

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Sensitive to pitch and intonation

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Demonstrative in speech and gesture

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Skillful in facilitating interaction

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Pre-disposed to comprehend grammatical analysis

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Self-disciplined and independent

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

B. SELF ASSESSMENT OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF YOU OWN APPLICATION OF TRANSFERENCE OF MUSICAL SKILLS AND TECHNIQUES IN TEACHING ENGLISH

- Syllable stress marking

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Feeling the beat by sounding the word out

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Percussion sequence

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Using open and closed palms

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Finger snapping

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Foot tapping/foot stomping

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Body percussion

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Tap on the desk

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Clap the hands

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Play simple instrument to emphasize loudness

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Use rubber band as a visual image for the length variation in syllables

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Use kazoos, etc. (an instrument that you play by holding it to your lips making sound into it)

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Humming

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Hand gestures to indicate pitch change (conducting)

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Directive gestures

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Counting/reading alound

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Using the metronome

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Ensemble experience

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

- Use of words and Mnemonics (Something, such as poem to remember a rule)

Excellent Above average Average Below average Poor

Part Three. Additional Information

Please encircle, underline or highlight your answer red. If there is a follow up question such as why and how, please answer.

- Did your employer know about your musical background when you were hired?

a. Yes b. No

If yes, do you think it is a big factor in why you were hired?

a. Yes b. No

- Do you view your musical background as strength when you apply for English teaching positions?

a. Yes b. No

- Do you think that there is a perception of musicians as capable ESL/EFL teachers in the Philippines?

a. Yes b. No

If yes, what do you base this view on? (Please write) ____________________________________________

- How many other musicians teaching ESL/EFL have you met?

a. 2-3 b. 3-4 c. 5-6 d. 7-8 e. 9 and above

- How does your musical ability and experience help you in the English language classroom?

- Chant a lot

- Aware of the proper pronunciation

- Aware of the stress and rhythm

- Improve my non-verbal communication

- Other (Please write) ____________________________________________

- What are some of the ways you use your musical skills indirectly in the classroom?

- Use them to improve student’s memory.

- Use them to lessen their stress when they are going to have an exam.

- Use them to relax.

- Others (Please write) ____________________________________________

- What are some of the ways you use your musical skills directly in the classroom?

- Use them to wake them up before the class starts

- Use them to motivate the students to study harder

- To improve their listening and speaking by let them listen to the music

- Others. Please write. ____________________________________________

- Have you used melody as a tool to improve students’ spoken intonation contours?

a. Yes b. No

If yes, how? (Please write) ____________________________________________

- Have you used rhythm drills to improve syllable stress? How?

a. Yes b. No

If yes, how? (Please write) __________________________________________

- Which category do you belong?

- Musicians (music major or well trained in music)

- Non-musical major but with certified music training (Please indicate your field of study)____________________________________________________________

- Non-musical major with no certified music training (Please indicate your field of study)____________________________________________________________

- Which languages/dialects do you speak in addition to Tagalog and English?

- Ilocano

- Pampangeno

- Pangasinese

- Cebuano

- Waray

- Ilongo

- Chavakano

- Bicol

- Other (please write) ____________________

- Which languages/dialects do you prefer to use at home in your daily life?

- English only

- Tagalog only

- Taglish

- A combination of your own regional dialect and English

- Other (please specify) ________________________

- What specific songs do you use in teaching your students?

A. Childrens songs (such as Incy Wincy Spider, Bingo, etc.) Please write some of the songs you use when teaching your students. Please indicate up to five of the songs you consider best for teaching.

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

B. English Pop songs (such as “Born this Way”, “Rolling in the Deep” etc.) Please

indicate the titles of the best five songs you are using when teaching English.

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

C. Popular Filipino English songs. If you use these songs, please indicate the titles of up to five songs you are using when teaching English.

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

D. Ilocano, Cebuano, Waray or any other songs from your own regions. If you use these songs, please indicate the titles of up to five songs you are using when teaching English.

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- ____________________________________________

- How often do you sing Karaoke? Please circle or highlight your answer

a. Never b. Seldom c. Sometimes d. Often e. Always

- What language do you consider your L1? (First language or mother tongue)

a. Tagalog b. Ilocano c. Ilongo d. Cebuano

e. Waray f. English g. please specify

- Which first language group do most of your students belong?

a. Filipino b. English c. Korean d. Japanese

e. Other (please specify)

Please check the English Improvement course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Multiple Intelligences course at Pilgrims website.

|