A Literature-based Approach for Motivating Adult EFL Learners

Mark Mallinder and Hsiang-Ni Lee, Taiwan

Mark Mallinder is an English instructor at National Changhua University of Education. He has been teaching a variety of college-level courses to Taiwanese EFL learners. His research interests include reading instruction and using multimedia in language classrooms. E-mail: markc@cc.ncue.edu.tw

Hsiang-Ni Lee is a professor at National Taitung University. She is interested in children’s literature, family literacy, literature-based reading instruction and material development. In the future, she also wishes to explore the multiple possibilities of utilizing technology in language education. E-mail: hnl@nttu.edu.tw

Menu

Introduction

Literature review

Methodology

Results

Discussion and implications

Limitations

Conclusion

Reference

In Taiwan, EFL writing has been a touchy subject. Due to the examination-driven curriculum, most of the English writing students are involved in middle schools is practically grammar-focused coupled with a great amount of drill practices. As a result of such product approach which disallow any grammatical errors, EFL writing has been long viewed by students as a chore they have to do for exam purposes rather than an enjoyable process of expressing their thoughts or ideas. Therefore, in this paper, we are interested in investigated whether a literature-based approach can be a useful tool for promoting students’ motivation to write.

Specifically, two specific research questions are examined:

- Have students shown any improvements over the three weeks of study in terms of quantity? In other words, have students demonstrated to be more fluent writers who feel more comfortable expressing their thoughts to a given topic?

- Have students shown any improvements over the three weeks of study in terms of quality? That is, have their writing shown to follow the typical English discourse pattern, i.e. start with a specific topic sentence, give well-developed supporting ideas and close with a focused statement tightly connected to the thesis?

As Shen (1989) suggested, learning to write in a second language is not only social but also cultural. However, because teachers mainly focus on correcting grammatical and syntactic errors in most Taiwanese EFL writing classes (González, Chen & Sanchez, 2001), students have not been able to enjoy writing as a fun way to explore issues and seek self-identity. Dong (2004) has proposed two ways of motivating low-level EFL writers. First, according to him (p. 173), journal writing is a useful strategy to reinforce students’ writing routines. Because journal writing often requires students to observe or reflect on a particular event, it can also encourage EFL students to become more creative and critical writers. In addition, Dong argued that a literature-based writing class which encourages free and genuine interpretations of a given text can provoke more responses from student writers (p.174). Since Rosenblatt’s reader response theory suggests that the transaction between the reader and the text is not only personal but also social (Lewis, 2000), L2 writers are free of coming up with one standard interpretation and thus might feel more comfortable expressing their thoughts.

Among various literature genres, picture books have been widely used in primary schools in order to promote children’s emergent literacy proficiency and in family literacy programs for adults with reading difficulties. Many scholars have discussed the effectiveness of using picture books in the classroom in order to promote language skills, raise intercultural awareness, encourage critical thinking as well as provide an incentive for more motivated writers. For example, Bishop (1992) suggested that multicultural books which provide authentic cultural-specific information prevent stereotypes and promote intercultural understanding among people with diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds. If properly guided, Lewison, Leland, Flint and Moler (2002) believed that the proliferation of social issue picture books enables students to critically examine certain social problems and thus encourage further action against injustice. Perhaps most important of all, picture books can be suitable teaching materials for students of all ages if carefully selected and presented in the classroom. (Chen, 2006; Ho, 2000; Kuo & Wang, 2010)

Participants and setting

Participants are 10 freshman English majors who are enrolled at a national teacher’s college in Taiwan. All the students, four males and six females, study English as a foreign language and have been admitted to the department with fairly high English scores on the National College Entrance English Exam. Despite their seemingly proficient language competence among the target age group, the instructor conducting this study (i.e. the first author of this paper) has observed varying degrees of difficulties students had with English writing. Mostly, students report having troubles getting started with English writing. Their written samples are rather short, which sometimes do not even fulfill the minimum length requirement. Also, their written samples often are in poor quality which, to the instructor, is a sign of either lacking the necessary writing skills to describe or reflect on a given event or simply a disinterest in English writing.

Materials

Three books were selected because they all dealt with the theme of war, which we thought that Taiwanese college students might find the subject interesting due to the local political tensions and the crackdown on terrorism worldwide. In addition, the pictures in all the books not only provided visual enjoyment but also gave rich information about the storylines. More specific information about the books are as follows:

- The Faithful Elephants (1997): This is a true story which happened during World War II. The Ueno Zoo in Tokyo decided to kill three elephants by starving them to death in order to ensure that the animals would not be able to escape from their cages and injure people if the city was attacked by enemy bombs. The elephant’s confusion and the zookeeper’s deep sorrow are vividly depicted throughout the entire story.

- The Bracelet (1996): This story tells the tale of a little American girl, of Japanese descent, who, along with her family, is sent to an internment camp during World War II. Prior to leaving her home, the girl receives a bracelet from a good friend, which she ultimately loses. While at first the girl is devastated by the loss of the bracelet, she ultimately learns that memories, not particular objects, are the most important things in life.

- Sweet Dried Apples (1996): This book also deals with the topic of war but in a less dramatic fashion than “The Faithful Elephants.” During wartime, two playful Vietnamese children are cared for by their mother and grandfather after their father leaves home to become a soldier. The story ends with the grandfather’s death and the mother and children being forced to move away.

Because it was our intention to show the picture books in their original form and color, all the reading materials were scanned and projected to a big screen so students could see the text and colored pictures with ease. In addition, the students also had individual computer monitors to look at for closer examination of the text and pictures.

Sources of Information

- Students’ writing samples

Each week, students were first read to one picture book and were asked to submit writing samples of minimum 200 words to the instructor via emails. Specifically, students were asked to write their reflections using four prompts: a) One thing to remember b) One question you have for the author or about the book? c) Does anything in the story that surprises you? d) Make one connection with your life.

- Survey data

After each week, students were required to fill out a brief survey stating their reactions to the book, i.e. their general feelings about the material and sorts of activities they had engaged in, if any, in order to find out the meanings of any words after the activity, etc.

Procedure

Due to a national holiday, the study was carried out on the first, second and fourth weeks of the academic semester.

- Pre-writing activity: Read-aloud

On the first day of class, the instructor briefly explained the reading activity students would be engaged in for the following weeks. For each week, the instructor read aloud one picture book to students. While reading, the instructor did not provide any explanation about the text of the story nor were any definitions given for the vocabulary words in any of the stories. The instructor read the story the second time to the same group of students the next day.

- Writing activity

Students were asked to respond to the weekly picture book using four writing prompts which described previously in this paper. Students were not given explicit instructions on how they would be graded except for the minimum length requirement and punctuality. It was the instructor’s effort to motivate students to become more courageous writers who felt comfortable exploring and expressing genuine ideas.

- Data analysis

Students’ writing samples would be analyzed in three different aspects. First, a word-count would be used to determine whether students had written more over time. Additionally, the sentence complexity of their writing samples would also be analyzed with the help of Microsoft Word software. Finally, a discourse analysis method was to help examine if students’ writing samples were able to demonstrate thoughtful arguments that were supported with evidence and critical evaluations. Furthermore, it was also our intention to examine if the arguments would follow the standard English organizational style.

Have students shown any improvements over the three weeks of study in terms of quantity?

Participating students’ writing samples have not seemed to improve steadily over the three weeks. First of all, although there was not distinct difference in students’ length of sentences over the weeks, they indeed made slight progress from writing 253.3 words per journal for the first week to 276.7 words for the second week. However, the quantity of their journals decreased to 261.6 words for the third week.

Similarly, the reading ease and corresponding readability grades of students’ writing samples also seemed to follow the pattern. The data has shown that students started to write more complex sentences over the first two weeks yet took a negative turn on the third week. (readability grade dropped to 6.2, see figure I. )

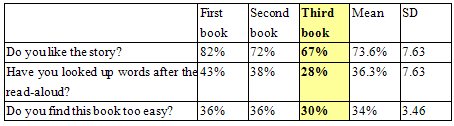

In terms of students’ reactions to the picture books, the survey data has shown that students liked the first picture book “The Faithful Elephants” the most, which resulted in 82% positive comments. Students reported that they liked the third book “Sweet Dried Apples” the least (67 %), referring to the story as either sad or boring. In addition, regarding the difficulty level of the books the students had read, an average of 34 % of participating students reported that they found the books to be too easy, which had slightly decreased when the third book was introduced to them. (Only 30 % of the students agreed “Sweet Dried Apples” was easy.) Knowledge of words was a distinct indicator of how students responded to the question of difficulty.

In general, the data has seemed to suggest that students’ interest level of the reading materials affected their writing. That is, students not only wrote less, they also used simpler sentence structures in the final week of the study.

Figure I. Analysis of students’ writing samples

Figure II. Survey summary

Have students shown any improvements over the three weeks of study in terms of quality?

Personal evaluation and connections

The data has shown that in response to the four prompts, the ten participating students were all able to give decent evaluation of the reading materials. That is, they were able to recall some specific and detailed facts from the picture books and had also demonstrated a fairly high degree of comprehension regarding the war issue. For instance, one student expressed regret toward the emotional and financial loss at a result of wars:

“I wanted to keep in mind that war is cruel. We should avoid making war. I thought people and animal is the most innocent when the war happened.” (Week1, student #3)

Another student had a similar opinion that war is unnecessary and thus should be avoided in the first place:

“War is one of the most dreadful things in the world. It will make our most dearing and loving things to leave us...” (Week1, student #10)

The students were also able to make personal connections with the stories by recalling stories or movies they had previously heard and watched. Due to the local cultural context, students frequently expressed concerns regarding the political tension between Mainland China and Taiwan as well as the difficult time during the Japanese occupation of the island decades ago. For example:

“ I am used to thinking if one day the POC declare war to we country, I will escape to a safe place to lead my rest of life. I know it is very selfish, but I don’t really want to stand up for someone to create this war… “(Week2, student #1)

“…My grandmother and grandfather encountered lots of difficulties during the time of Japanese governed. They also faced with coercion, instability, hard famine, bad economy, and death.”(Week3, student #6)

Somewhat surprisingly, only one student had related the war issue to the 9-11 terrorism attack happened in the U.S. although some did attempt to discuss the perceived rampant racism in the States and the anti-Semitism during World War II.

In general, when being assigned to write about a somewhat challenging topic of war, participating students were able to form personal opinions by recalling facts from the books or making personal connections. However, their writing sometimes lacked coherence, i.e. missing transitional words between ideas and specific elaborations on how their prior experiences or recalled anecdotes related to the thesis. The latter major flaw, namely missing supporting ideas, is discussed in more details below.

Some supporting ideas

After taking a stance on the war issue, students were generally able to support their arguments by providing some evidence. That is, after pointing out the negative outcome of wars, they managed to give further details or such statements. Take one student’s writing for example:

“After I read the article, what kept in my mind is the grandfather was really a kind and responsible man. He not only protected his family from harm but also volunteer to take care of the injured by providing his medicine to the dangerous region… We all know it is difficult to sacrifice oneself to serve the others especially our own precious lives.” (Week3, student #7)

In this passage, the student gave explicit examples provided by the book to support her statement that the character was an honorable man. Two other examples of students’ efforts to support their argument are as follows:

“ In my viewpoint, I would like to keep in mind that war is cruel and terrible absolutely. Such stupid and meaningless action may force lots of families to apart from their relatives or even never see each other again.” (Week 2, student 2)

“I want to keep in my mind that war is nothing but cruel. It contributes many people doing what they do not want to do, such the men are forced to take part in army, and the wives and children should bear that their husbands and fathers left away. For men are the main supporters of economics, if the men are forced to leave away their house, and their families’ economic became worse and worse.” (Week 3, student #5)

Even though this last student’s final statement was a repeat of the same argument he was trying to make in the previous sentence and thus was redundant, it was clear that she was able to go beyond making a general statement to providing readers with more specific evidence.

However, in response to the fourth writing prompt, which was “making one connection”, some students managed to write touching stories that they either personally experienced or learned from TV and movies but had not specify how the stories were related to the topic. A linear description of a story was only sensible to the instructor and I yet unsatisfactory to the general public due to its loose tide to the intended arguments they stated earlier. Take student # nine’s reflective journal for example:

“This story reminds me of a popular issue that has been discussed recently. That is, merchants kill raccoons only to get their furs to make clothing. The fur clothing sellers think about their profits instead of the wailings of little raccoons. They kill the raccoons alive. No matter how the raccoons struggle to escape from the atrocious butchers, the butchers stripe the raccoons’ covering furs off without any sympathy. Furthermore, I saw the film about the process of killing raccoons on TV. It’s terrible! I can even hear the crying of the raccoons! Therefore, I hope that the kind of thing won’t happen again and people.”(from week 1)

This student learned about the brutal process of killing animals to make fur coats from TV news and immediately made connections with the “Faithful Elephants” story. Despite the fact that she was able to give details about the news, she had not provided specific reasons as to why she made the association between the picture book and the news. Nor did she make a more persuasive conclusion based on the connection she specified. Such lacking elaboration could be that the students were asked to write four individual passages and thus were not taking into account the cohesion between paragraphs. Another plausible explanation was that students were writing the reflective journals to the course instructor instead of the general public and thus did not feel the need to make careful connections between ideas. That is, since the instructor was familiar with the materials, students felt they did not have to put forth efforts establishing the causal relationship between the story and their arguments.

Critical analyses are mostly missing

Lack of solutions

In general, the participating students had not shown to be able to give critical examination of the assigned topic in their reflective journals. In response to the second and the third writing prompts, namely whether they had any questions or surprises for the stories, most students expressed confusion with respect to the development of the story plots. For example, for week 2’s reading, they wondered how Emmi, the little girl, could have lost the bracelet. Similarly, they also asked where the family had eventually moved to and wondered how the father would ever find out where they were for “Sweet Dried Apples”:

“I want to ask that why their grandfather persist in going out for sailing. In fact, it does not matter whether he earns the money or not, but should put great emphasis on the lost of his life. So why he insist on going out, leaving his daughter and his grandchildren away?”(Week 3, Student #3)

It should be noted that students had expressed most confusion regarding week 2’s reading due to a lack of understanding of the story while for week 1 and 3, their questions were more a request for further elaborations.

Additionally, after proposing questions, very few students were able to come up with specific solutions with respect to how the unfortunate situation could be fixed or avoided. Two students made attempted to offer solutions as to how the tragic starvation could be prevented,

“I do not understand why the army must put the fierce or big animals to death, instead, trying to find some the other ways to preserve the animals’ lives. There must be some solutions, such as injecting medicine making they sleep and then finding other safe places to let the animals stay there for a period of time.”(Week1, student #5)

“… There was still another way that can solve the problem. For example, they could take those animals to the deep mountains or broad fields where common people would get there easily. Moreover, those places are the original places and their hometown.”(Week 1, student #7)

Unlike other students’ responses which mainly focused on the cruelty of those zookeepers to let the animals die, these two students tried to think of solutions that it could, in effect, could have been avoided.

Barely gaining new insights

Several interesting discussions had arisen from students’ reflective journals, namely animal rights, precious memories and one’s devotion to his/her work. Again, even though all participating students were able to touch on the themes presented in the reading, very few of them were able to critically synthesize and evaluate the provided topic. One student wrote an insightful reflection on never giving up hope during difficult time:

“Recently I had read the Little Prince, for it was an assigned reading book. The little prince said, “ What makes the desert beautiful is somewhere it hides a well.” No matter how hard the life is, we will find the well of hopes in the desert if we continue trying. In my opinion, life is combinations of challenges and joy, and we should prepare for the challenge when we are joyful. “(Week2, student #1)

This student gave a thoughtful argument with an example from “Little Prince”. Right away, the student’s use of a metaphor between a well in the desert and remaining optimism during a difficult time of his life was vivid and his point was easy to understand.

Another student also attempted to use a metaphor when commenting on the value of one’s memories:

“I am deeply surprised that the little girl, in the long run, came to the realization that memory won’t be lost only because the losing of the bracelet or other thing. As people, neither by photograph nor by relics of the deceased could you remind an old friend; in fact, it’s the box of the memory that enable you to remind the bygones.” (Week 2, student #2)

These two writing examples differ from others because students were able to provide clear images as examples rather than mere straightforward statements such as “memories cannot be taken away”. In general, at this stage of their writing development, students seem to not use metaphors very frequently.

A final example comes from a student who gave a thoughtful reflection on the distinctions between so-called civilized human beings and primitive villagers during ancient times:

“The war brought away not only human beings lives but wild animal lives. In fact, for the barbarism they merely killed the animals for a enough amount so as to live for their own lives, or they would die in starvation. On the contrary, for the civilized they killed anything that they think that he or she or it is a barrier, they neglect the value that the wild animals brought forth for we mankind…” (Week 1, student #2)

Even though the sentences were occasionally confusing and awkwardly written, the student made an interesting observation about how ancient villagers took animals’ lives in order to survive but modern people have a tendency to kill for greed. Therefore, he raised an intriguing issue that could be developed into a promising essay on why wars were sometimes started.

Based on the study results, there is no doubt that with the assistance of literature as writing prompts, adult EFL students are able to take positions, generate evidence for their arguments as well as sometimes give critical reflections even on controversial issues such as wars. Thus, we will focus our discussion on two issues that have arisen from the study; that is, which factor, time or selected materials, triggers more writing? In addition, for EFL student writers, how much attention should be directed to format and style of writing without the expense of rich and creative ideas?

Role of reading materials in facilitating writing

In this study, students started to produce more writing over the first two weeks but the amount of words they used and the sentence complexity with which they wrote had both decreased for the third week. Although such decrease could have resulted from the exhaustion of those participating in the study, it was also likely that students were simply unable to write about a story that they had reported to like the least as well as had expressed most difficulties comprehending. In fact, for the first two picture books, students on the average were able to describe more details along with sometimes giving insightful observation whereas for the last story, they were mostly able to recalled facts and anecdotes. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that in order to involve students in the pre-writing activities and ultimately help them produce better final products, the reading materials which serve as writing prompts must be stimulating and challenging to the students.

Balance between content and format/style training

González, Chen and Sanchez’s 2001 study has suggested that Chinese EFL learners tended to write in an “indirect and inductive” fashion which did not conform to the rhetoric discourse organization as expected in English writing. For instance, they might start or close a topic with a general statement. In addition, despite transitional words used between sentences, the variety of ideas was often loosely connected without a linear reasoning sequencing. Furthermore, due to a negative L1 transfer, Chinese EFL writers sometimes focus on the style at the expense of clarity in the writing resulting in repetitive descriptions about one single idea. Because the main focus of this paper was to examine whether a literature-based approach could help motivate students to write more in English, the organizational styles and formats are neither the main concern nor the criteria for assessment. However, it is indeed a constant dilemma for EFL writing teachers and thus requires professional decisions: That is, after teachers have managed to achieve the goal of making students feel comfortable with English composition, how do they keep a balance between the a focus on ideas and details versus the correct form and style so that the final products will be culturally comprehensible to native speakers of English? More specifically, after students’ fluency of writing has improved, when and how can teachers do to help increase the accuracy, i.e. grammar and choice of words, as well as the direct and specific-to-general organizational style? Will such switch of focus cause a decrease in students’ motivation to write and if so, how can it be prevented or mitigated?

Three limitations of this study should be explained before any generalization is made. First, this study did not use a control group. Because the data was collected as part of the regular class assignments, a pre and post comparison of students’ writing samples is unavailable, either. Secondly, it used a relatively small sample size. Finally, three weeks might not be sufficient to expect significant improvements as writing skills often require a greater length of time in addition to extensive practices.

This study has shown that, when provided with multicultural picture books, EFL students are able to generate decent discussions on issues which normally might be difficult to write about. Even though students’ discussions are not all supported by evidence nor followed up with further elaboration, the initial drafts they produced have indeed shown potentials for turning into thoughtful essays. It is our intention to conduct a longitude study to investigate if student are able to become more motivated writers in such literature-based classes and how, if any, their writing products differ in any way than those who receive more deductive, grammar-oriented writing training.

Bishop, R., & Hickman, J. (1992). Four or fourteen or forty: Picture books are for everyone. In Benedict, S. & Carlisle, L. (Eds), Beyond words: Picture books for older readers and writers (pp. 1-10). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Chen, Y. M. (2006). Using children’s literature for reading and writing stories. Asian EFL Journal, 8(4), 210–232.

Dong, Y. R. (2004). Preparing secondary subject area teachers to teach linguistically and culturally diverse students. Clearing House, 77(5), 202.

González, V., Chen, C. Y., & Sanchez, C. (2001). Cultural thinking and discourse organizational patterns influencing writing skills in a Chinese English-as-a-foreign-language (EFL) learner. Bilingual Research Journal, 25(4), 627-652.

Ho, L. (2000). Children’s Literature in adult education. Children’s Literature in Education, 31(4), 259-270.

Kuo, J. M., & Wang, T. F. (2010). Incorporating Children's Literature and Multimodal Pedagogy in EFL Instruction. Hwa Kang English Journal, 16, 61-89.

Lewis, C. (2000). Critical issues: limits of identifications: the personal, pleasurable, and critical in reader response. Journal of Literacy research, 32(2): 253-266.

Lewison, M., Leland, C., Flint, A. S., & Moler, K. (2002). Dangerous discourses: Using controversial books to support engagement, diversity, and democracy. New Advocate, 15(3), 215-226.

Shen, F. (1989). The classroom and the wider culture: Identity as a key to learning English composition. College composition and communication, 40(4), 459-466.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching English Across the Curriculum course at Pilgrims website.

|