The Consolidation of Life Issues and Language Teaching on the Life-Language Model of Emotioncy

Reza Pishghadam and Shaghayegh Shayesteh, Iran

Reza Pishghadam is a professor of language education and a courtesy professor of educational psychology at Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran. In 2007, he was selected to become a member of Iran`s National Foundation of Elites. In 2010, he was classified as the distinguished researcher of humanities in Iran. In 2014, he also received the distinguished professor award from Ferdowsi Academic Foundation, Iran. E-mail: pishghadam@um.ac.ir

Shaghayegh Shayesteh is a PhD candidate studying teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL) at Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran. In 2016, she was selected to become a member of Iran`s National Foundation of Elites. E-mail: shaghayegh.shayesteh@gmail.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Theoretical background

Life-language model of emotioncy

Concluding remarks

References

The rapid changes of globalization affect every aspect of human life including education. Incorporation of life matters in the schools’ curricula has been one of the considerations to enable learners to deal with unforeseen life challenges of this era. Due to the unique nature of English language classes, they have been regarded as sites which boost life skills in learners. As a complementary view, in the current study we suggest the psychological concept of sensory emotioncy (emotion + frequency) as an element which may facilitate the process of language learning by linking learners’ life in general and sensory experiences in particular to language. To this end, we extended the recently proposed model of emotioncy in such a way to elucidate its life dimension. We explained that during the early exposures (exvolvement) learners deal with forms and functions of a language. Later, while fully involved they come to applection and appropriation (involvement) which reflect the manifestations of a real life. In fact, we introduced the term applection (application + reflection) to jointly stress synthesis, analysis, and evaluation as the fundamental necessities of today’s life. In the end, we came up with two practical examples to draw a picture of its application in the field of English language education.

Incorporating life issues into a language learning class has been a matter of high importance to language educators (e.g., Brinton, Snow, & Wesche, 1989; Littlewood, 1984; Schneck, 1978). Language and life are so intertwined that separating them from each other can damage authenticity, especially in a foreign language context. This is why, the newly-written textbooks for teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) are replete with life issues, and especial syllabi have been proposed to underscore the role of life issues in learning English (Crystal, 1997). Recently, emotioncy as a new concept in psychology has been introduced (Pishghadam, Adamson, & Shayesteh, 2013; Pishghadam, Tabatabaeyan, & Navari, 2013), which is supposed to have the potential to bring language and life together.

Emotioncy was developed by Pishghadam, Tabatabaeyan, and Navari (2013) to place emphasis on the roles of senses and emotions in affecting understanding and interpretation. It is believed that the senses from which we receive information can evoke emotions which can relativize cognition (Pishghadam, Jajarmi, & Shayesteh, 2016). According to Pishghadam (2015), emotioncy ranges from avolvement (null) and exvolvement (auditory, visual, & kinesthetic), to involvement (inner & arch). As for exvolvement, form and meaning of a language are dealt with, while as for involvement, applection (application & reflection) and appropriation are taken into consideration (Figure 1). In fact, while the former deals with the linguistic aspects of language learning, the latter is related to life issues.

All in all, due to the significance of relating language to life issues to enhance authenticity and improve learning a second language, it seems that emotioncy can provide us with a new framework based on which we can relate language (form and function) to life (applection and appropriation) systematically. Thus in this study, we attempt first to cover the literature related to life education and emotioncy, second to present a model of emotioncy which displays the interface between language and life, and finally to provide the readers with some practical examples in EFL learning.

Life education

Having its roots in the core principles of humanistic psychology which came to the fore in response to Freudian and behavioristic approaches, humanistic education (formerly known as person-centered education) steered the focus on “free choice” and “emotional integration into the learning process” (Bell & Schniedewind, 1987, p. 56). Humanistic education unifies cognitive and emotional dimensions of learning explaining that learners’ feelings and thoughts are inevitable resources to create personal meanings. From this perspective, learning is, in fact, a matter of personal discovery of meaning or exposure to new experiences. As to its experiential structure, experiences of the world are indicators of effective learning (Combs, 1981).

Indeed, there exists an integral nexus between education and life or experience. “Experience is educative” and “education is the cumulative aspect of experience” (Ross, 1966, p. 98). As a generative assumption of humanistic education, “there is only one subject-matter for education, and that is life in all its manifestations” (Whitehead, 1929, p. 6). That is, educational instructions should not be confined to mathematics, science, or literature, yet should cover emotions, thinking styles, and social relations as well (Pishghadam & Zabihi, 2012). In this light, Dewey (1938, p. 86-87) claims that, any subject “whether arithmetic, history, geography, or one of the natural sciences must be derived from the materials which at the outset fall within the scope of ordinary life experience”. Hence, in order to reach successful education, pedagogical matters should be linked to their implications in life (Ross, 1966).

In this sense, the inevitable aim of education at all levels would be to make humanity achieve the actual purpose of life. The prerequisite of this outlook, generally referred to as life skills education, is to reinforce effective communication in an interactive environment and enable learners to develop abilities to deal adequately with the ever-changing challenges, demands, and hassles of daily life through education. According to Rousseau (1979, p. 41-42), “prior to the calling of his parents is nature’s call to human life. Living is the job I want to teach him. He will, in the first place, be a man. All that a man should be”. When life turns into the chief ingredient of pedagogy, it basically functions as the starting point of every educational activity in such a way that life practices form the instructional concepts and curriculum knowledge (Zhengtao, 2004).

During the course of time, experts such as Dewey (1938), Freire (1998), Krishnamurti (1981), and Walters (1997) purposefully injected life into the realm of education, believing that the system of education is slavish and thoughtless; “leaving us incomplete, stultified, and uncreative” (Krishnamurti, 1981, p. 7). With the emergence of communicative methodologies in the 1980s, a number of language experts (e.g., Brinton et al., 1989; Littlewood, 1984; Schneck, 1978) equally lingered to implicitly take everyday life issues into account. Despite all, the outcome could satisfy neither the educators nor the learners. Wenzhong and Youzhong (2006, p. 243) argue that, “English language education is faced with the danger of trivializing education by reducing it to vocational training”. Addressing similar concerns, in 2011, Pishghadam pioneered to change the status quo of English language education. He reformed theorizers’ and practitioners’ conventional understanding of the field of English language teaching (ELT) and proposed the concept of Applied ELT which grew out of the view that taking advantage of the findings of various fields of study (e.g., psychology, sociology, neurology, etc.) for years, ELT is now ripe enough to contribute to life and other domains of knowledge as a full-fledged autonomous discipline. In this view, “only-language classes” turn into “life-and-language classes” so as to train whole person individuals (Pishghadam, 2011, p. 13). The so-called Life Syllabus (Pishghadam & Zabihi, 2012) is correspondingly devised to direct teachers’, referred to as educational language teachers (Pishghadam, Zabihi, & Kermanshahi, 2012), attention to prioritize critical thinking, creativity, social, and emotional intelligence, etc., holding that “language must be at the service of enhancing life qualities” (Pishghadam, 2011, p. 13). A couple of years later, in 2013, Pishghadam, Adamson et al. came up with a novel psychological concept called emotioncy to breathe a new life into the field of language education.

Emotioncy

Corroborating emotion as the pivotal missing piece in language education and leaning on Greenspan’s (1992) developmental individual-difference relationship-based (DIR) model of first language (L1) acquisition, encompassing affect and supportive relationships as its primary constituents, Pishghadam, Adamson et al. (2013) introduced a fresh approach to the field of second language (L2) education called emotion-based language instruction (EBLI). EBLI lays emphasis on giving prominence to the emotions learners transfer from their L1 experiences and is structurally defined under three leading concepts of emotioncy, emotionalization, and inter-emotionality (Pishghadam, Adamson et al., 2013). Different degrees of emotion evoked by senses while encountering any language entity is referred to as emotioncy. To explicate, certain individuals may benefit from higher levels of emotioncy for some items/concepts which they have heard about, touched, or experienced most often. In this situation, the pace and quality of learning may surpass the opposite state that the learner has little or no emotioncy for the item/concept. This argument is actually underpinned by Pishghadam’s (2015) idea of sensory constructivism which regards senses as a path to individual’s conception of the world.

To develop the concept, Pishghadam (2015) broke emotioncy down into different kinds and types in a hierarchical order (Figure 1): Null emotioncy (0), Auditory emotioncy (1), Visual emotioncy (2), Kinesthetic emotioncy (3), Inner emotioncy (4), and Arch emotioncy (5). Pishghadam (2015, 2016a, 2016c) also featured Avolvement (Null), Exvolvement (indirect involvement initiating with Auditory emotioncy), and Involvement (full internalization of a concept through direct involvement) as its different types which acknowledge a recognition of the world fluctuating from hyper/hypo reality to reality. This sets the theoretical foundation of sensory relativism put forth by Pishghadam, Jajarmi et al. (2016), delineating that sensory emotions are able to relativize cognition.

With regards to the second leading concept, emotionalization revolves around establishing emotions for L2 lexical items. The emotional shift between L1 and L2 lexical items provides the learners with the prepossessed pragmatic aspect of the language (world) to the point that the teachers need to teach the semantic aspect of the language (word) only (Pishghadam, Adamson et al., 2013; Pishghadam, Shayesteh, & Rahmani, 2016). This bidirectional emotional flow between L1 and L2 explains the third leading concept of EBLI known as inter-emotionality.

Hitherto, the newly developed concept of emotioncy has been the major objective of a number of different studies. It has been recognized as an indicator of word saliency (Pishghadam & Shayesteh, 2016) leading to better comprehension and retention (Pishghadam, 2016a), as a potential source of test bias (Pishghadam, Baghaei, & Seyednozadi, in press), and as a complementary source of measuring readability of texts (Pishghadam & Abbasnejad, 2016). It has similarly been associated with learners’ willingness to communicate (WTC) (Pishghadam, 2016b) and employed as a criterion of sorting out culture teaching strategies (Pishghadam, Rahmani, & Shayesteh, in press). Emotioncy has also been marked as a critical means of freeing up working memory and cutting back on cognitive load (Pishghadam, 2016a).

On the whole, it is believed that the multidimensional concept of emotioncy can help individuals reach their full potentials through proper education. Although emotioncy is broached as a psychological term, its contributions could be extended to other domains as well. That is to say, different indicators of life quality such as social relations, physical health, happiness, and so on (Pishghadam & Zabihi, 2012) may be improved by enriching the emotional flow between the languages. Depending on its experiential nature, emotioncy can act as a bond to tighten the knot of life and language. Apart from the unique features of ELT classes which promote life quality, the emotional experiences learners bring into play from their L1 can likewise encourage teachers and educators to relate life issues to language and speed up the process of language learning.

Subsequent to reviewing the literature of life education and emotioncy, we now intend to shed more light on the application of emotioncy in L2 teaching and learning. Employing the emotioncy concept in second language education, we can claim that during exvolvement, individuals hear, see, and experience a concept, which may contribute to acquiring the forms and the functions of the words related to the concept. To highly emotionalize the words and to get the learners involve in the process of learning words, the teacher can use applection and appropriation. Applection which is a blend of application and reflection means that, teachers should apply the newly learned words to real life situations, making the learners synthesize, analyze, and even evaluate (using Bloom, Englehart, Furst, Hill, & Krathwohl’s (1956) terms) what they have already learned. When they practice in this way, after some time the learners can appropriate the words. Appropriation means words become one’s own when they are infused with the real intentions (Bakhtin, 1981). It is our belief that when the learners applect a word, gradually they internalize the word, make it their own property, and display proximal emotions for it. In sum, As Figure 1 shows, exvolvement focuses on the linguistic aspects (Form & meaning) while involvement deals with the life dimensions (applection & appropriation) of learning a language.

Figure 1

Life-Language Model of Emotioncy

The following examples are provided to clarify the above-mentioned points.

Example 1

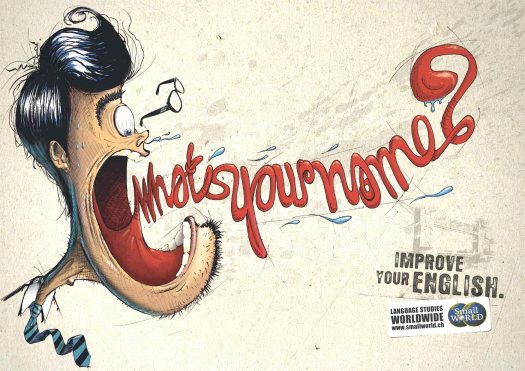

Generally one of the phrases which is taught at the very beginning of learning English is What’s your name?

Source: http://adsoftheworld.com/media/print/small_world_whats_your_name

Teachers using explanation or translation try to convey the meaning of this phrase. Students first hear the phrase, and then they come to know the meaning of it. Teachers ask the question and students are supposed to introduce themselves until they get familiar with both form and meaning of the phrase. Irrespective of any especial teaching method, this seems to be the common way of teaching this phrase in English. In fact, using emotioncy terminologies, students may hear the phrase (auditory emotioncy) see teachers` modeling (visual emotioncy), or even move in class to ask questions or play a game (kinesthetic emotioncy) to master the form and the meaning of the phrase. So far so good. Up until now, students have been exvolved into this phrase, knowing the form and the meaning of what’s your name?

The next step is to make the students get involved in learning this phrase. To do so, teachers are supposed to applect it in a way that it is applied to a real life situation and students reflect on that. For instance, one of the debates in Iran is whether parents name their kids after the Islamic or Iranian figures. This can reveal the parents’ identity to see whether it is religious or national. Getting back to the example of what’s your name?, we believe that after mastering the form and the function of this phrase, this time teachers can ask students to tell their names and write them on the board. Then, teachers can ask students to think for a moment to determine which name is Islamic or Iranian. The students also can be asked to measure the percentage of Islamic and Iranian names to sensitize them to the probable differences. This example shows how language and life can be tied together, making students think and appropriate the language in a course of time.

Example 2

Imagine as a teacher you like to teach more/less expensive.

Source: www.targetcomponents.co.uk/shoptalk/competing_credibly/thats_too_expensive

Generally, in non-English countries, the commercial books written by the English native speakers are taught. These books may use life issues to enhance the authenticity of the materials. However, there is a big problem. Life issues are not necessarily universal. For instance, Iranians have a problem with the foreign products sold in the country. To involve the learners, the teachers can emotionalize more/less expensive by using sentences such as:

The Chinese products are less expensive than the Iranian ones.

The local clothes are more expensive than the foreign ones.

These sentences make the students think about their own lives, trying to use English to analyze the issue once more in another language. This can help the process of critical thinking and give a pragmatic and utilitarian mode to leaning English. Fully practiced in this way, the learners feel closer to the language, trying to project their own identity through it.

As already mentioned, the major objective of this study was to use the newly proposed concept of emotioncy as a new perspective to relate language and life issues so as to enhance authenticity and expedite the process of learning English. To do so, we claimed that forms and meanings are learned during exvolvement and applection and appropriation occur during involvement. We coined the word applection to give more prominence to application, synthesis, analysis, and evaluation (starting from the simplest to the most complicated one) as the top levels of Bloom et al.’s (1956) taxonomy in leaning a new language. According to Bloom et al. (1956), these cognitive categories stand against memorization or so-called rote learning.

We also used the word appropriation to show that learners can have their own identity, feel words deeply, and create new concepts and words. This image is an amalgamation of the revised edition of Bloom’s taxonomy which replaces creation with synthesis (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001) and Bakhtin’s (1981) appropriation which gives rise to apprehension, internalization, and recreation. The common focus of the two views on creation is an inevitable prerequisite of the unpredictable challenges of living in the globalization era.

As the literature of emotioncy reveals, emotionalization fully occurs when we move from exvolvement to involvement. This process of emotionalization should not take a long time to happen in order to use the language more effectively. During exvolvement, auditory, visual, and kinesthetic inputs are provided to familiarize the learners with the forms and meanings of the English concepts and words. In this regard, great care should be exercised to improve the quality of emotioncy by positivising the language learning experience. In fact, EFL emotions generated by different language exercises, and tasks are supposed to be positive and activating, encouraging the learners to move up to the next level of emotioncy which deals with inner and arch emotioncies. Quite similar to Bloom’s taxonomy, in order to reach higher-order thinking and creation learners should start building the necessary skills from the lower levels (Bloom et al., 1965). While Bloom’s hierarchy varies on the basis of increased complexity, emotioncy ranges according to the degree and depth of involvement.

As for involvement, teachers try to relate the newly learned materials to the local real life situations in a way that the learners synthesize, analyze, and evaluate their experiences in another language. Going beyond the four walls of the language learning classroom can be an exhilarating experience, especially when it leads to more understanding. When language and life are fully connected, the learners may have inner emotioncy and feel the components of language more deeply and differently. Appropriation occurs when the teachers have attended to both the quality (positive emotions) and quantity (practice and exposure) of emotioncy for all components of learning another language. Here is the time when the learners use language to their own benefit and project their own identities through the new language.

On the whole, despite miscellaneous studies conducted in the field, concluding that educational systems need to prepare learners to overcome everyday life challenges, after almost half a century, we are still of the same mind with Ross (1966) that, the school subjects that students learn, have little or no contribution to their quality of life. Be that as it may, the idea of emotioncy seems to have the potential to be applied to learning a new language. As emotioncy integrates sense, emotion, and cognition, it is our understanding that it can be utilized as a further life-enhancer criterion in learning another language by merging life into language. The newly-proposed term of applection in this study may provide a new challenge for language educators in order to design the materials to move the learners from exvolvement to involvement. Teachers, perhaps more than others, are in close contact with the students and, therefore, need to be trained in a way to be able to fully implement the practice-based mode of emotionalization flavored with life matter considerations. To this end, the teachers have to use the local and glocal issues which are more thought-provoking, and as Freire (1998) has already put it: critical, empowering, and emancipatory. In the end, it is our hope that the proposed model of language learning can open up new horizons for the language educators to seek for more systematic approaches of learning a new language which are more pragmatic and authentic.

Anderson, L.W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays (C. Emerson, Trans., M. Holquist, Ed.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Bell, L., & Schniedewind, N. (1987). Reflective minds, intentional hearts: Joining humanistic education and critical theory. Journal of Education, 169(2), 55-72.

Bloom, B., Englehart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. New York, Toronto: Longmans, Green.

Brinton, D. M., Snow, M. A., & Wesche, M. B. (1989). Content-based second language instruction. New York: Newbury House.

Combs, A. W. (1981). Humanistic education: Too tender for a tough world? Phi Delta Kappan, 62, 446–449.

Crystal, D. (1997). English as a global language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. USA: Kappa Delta Pi.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Greenspan, S. I. (1992). Infancy and early childhood: The practice of clinical assessment and intervention with emotional and developmental challenges. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

Krishnamurti, J. (1981). Education and the significance of life. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Littlewood, W. (1984). Foreign and second language learning: Language-acquisition research and its implications for the classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pishghadam, R. (2011). Introducing applied ELT as a new approach in second/foreign language studies. Iranian EFL Journal, 7(2), 9-20.

Pishghadam, R. (2015, October). Emotioncy in language education: From exvolvement to involvement. Paper presented at the 2nd Conference on Interdisciplinary Approaches on Language Teaching, Literature, and Translation Studies. Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran.

Pishghadam, R. (2016a, May). Giving a boost to the working memory: Emotioncy and cognitive load theory. Paper presented at the 1st National Conference on English Language Teaching, Literature, and Translation. Ghoochan, Iran.

Pishghadam, R. (2016b). Emotioncy, extraversion, and anxiety in willingness to communicate in English. In W. A. Lokman, F. M. Fazidah, I. Salahuddin, & I. A. W. Mohd, (eds.), Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Language, Education, and Innovation (pp. 1-5). UK: Infobase Creation Sdn Bhd.

Pishghadam, R. (2016c, September). Introducing emotioncy tension as a potential source of identity crisis. Paper presented at the 16th Interdisciplinary Conference on Cultural Identity and Philosophy of the Self. Turkey, Istanbul.

Pishghadam, R., & Abbasnejad, H. (2016). Emotioncy: A potential measure of readability. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 9 (1), 109-123.

Pishghadam, R., Adamson, B., & Shayesteh, Sh. (2013). Emotion-based language instruction (EBLI) as a new perspective in bilingual education. Multilingual Education, 3(9), 1-16.

Pishghadam, R., Baghaei, P., & Seyednozadi, Z. (in press). Introducing emotioncy as a potential source of test bias: A mixed Rasch modeling study. International Journal of Testing.

Pishghadam, R., Jajarmi, H., & Shayesteh, Sh. (2016). Conceptualizing sensory relativism in light of emotioncy: A movement beyond linguistic relativism. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 4 (2), 11-21.

Pishghadam, R., Rahmani, S., & Shayesteh, Sh. (in press). Compartmentalizing culture teaching strategies under an emotioncy-based model. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences.

Pishghadam, R., & Shayesteh, Sh (2016). Emotioncy: A post-linguistic approach toward vocabulary learning and retention. Sri Lanka Journal of Social Sciences, 39 (1), 27-36.

Pishghadam, R., Shayesteh, Sh., & Rahmani, S. (2016). Contextualization-emotionalization interface: A case of teacher effectiveness. Effectiveness. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 5(2), 97-127.

Pishghadam, R, Tabatabaeyan, M. S., & Navari, S. (2013). A critical and practical analysis of first language acquisition theories: The origin and development. Iran, Mashhad: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad Publications.

Pishghadam, R., & Zabihi, R. (2012). Life syllabus: A new research agenda in English language teaching. Perspectives, 19(1), 23–27.

Pishghadam, R., Zabihi, R., & Kermanshahi, P. (2012). Educational language teaching: A new movement beyond reflective/critical teaching. Life Science Journal, 9(1), 892-899.

Ross, S. (1966). The meaning of education. Netherlands: Springer.

Rousseau, J. J. (1979). Emile or on education (A. Bloom, Trans.). New York: Basic Books.

Schneck, E. A. (1978). A guide to identifying high school graduation competencies. Portland: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory.

Walters, J. D. (1997). Education for life: Preparing children to meet the challenges. Nevada, CA: Crystal Clarity Publishers.

Wenzhong, H., & Youzhong, S. (2006). On strengthening humanistic education in the English language curriculum. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 5, 243-247.

Whitehead, A. N. (1929). The aims of education and other essays. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Zhengtao, L. (2004). On the life dimensions of pedagogy. Educational Research, 4, 1-9.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Improvement course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|