Online Discussions as a Way to Support Verbal Skills: Perception and Outcomes

Heather M. Austin, Turkey

Heather is an English language instructor who graduated with a BS in Interdisciplinary Studies and a TEFL certification from the University of Central Florida. She moved to Turkey from the USA in 2012 and completed her Cambridge ICELT. She teaches at Izmir University of Economics and is a member of the Curriculum and Materials Development Unit. Her professional insterests involve technology in the language classroom and curriculum and materials development. She is currently a graduate student of Applied Linguistics at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. E-mail: hmaustin@live.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Literature review

Methodology

Data collection tools

Data analysis

Results

Limitations and implications

Conclusion

References

Appendix

This action research considers whether asynchronous online discussions can help improve students’ speaking skills. It also looks at students’ perceptions of using online interactive components in their language learning as well as the teacher’s experiences in and reflections on implementing the research.

In this day and age, technology has affected nearly every part of our lives. Since the 1980s when electronic communication found its way into the language learning classroom (Warschauer, 1996), the field of ELT has seen many changes influenced by technology, from interactive whiteboards and digibooks to record keeping and assessment methods. Thanks to digital tools, new layers of interaction have been added to the ways in which we communicate with one another, and this applies to the language learning classroom by no exception. Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) and Technology Enhanced Language Learning (TELL) are ever growing fields and many advancements have been made, particularly involving the ways in which teachers and students utilize technology to support second language (L2) learning as well as to create further opportunities for L2 learning to occur. Online components of language learning coursework are becoming more common, especially as more and more institutions feel the pressure to integrate technology into their existing educational frameworks (Walker & White, 2013). Finding ways to help students prepare for and become more comfortable with producing in English has always been a challenge for teachers, and many believe that technology can be a means to achieve this. Such was the case for this action research in which asynchronous online discussions via the Blackboard Learning Management System (LMS) were incorporated into an English preparatory course at a university in Turkey. For clarification purposes, it should be noted that asynchronous online discussions and online discussions are used interchangeably in this report to mean the same thing unless otherwise specified.

With all of this in mind, the aim of this study was to discover if using asynchronous online discussions could help to improve actual verbal skills in face-to-face discussions as well as to learn how students perceive using online interactive components in their L2 learning. The goal was not to see if asynchronous discussions could have the same effects as synchronous discussions (for more on this comparison, see Johnson, 2006), but rather to see if asynchronous online discussions can prepare students for verbal discussions on the premise that such digital interactions can afford learners an interactive foundation from which they can grow to improve their productive skills. Therefore, online discussions were implemented in student coursework as a way of potentially preparing students for oral discussions in class and in speaking assessments as well as to collect feedback from students about the use of such technology in their English studies. Learners were presented with video input and required to respond to it with the aid of guiding questions, and then they were required to respond to at least one of their classmates using functional language appropriate for discussions (giving an opinion, agreeing, disagreeing, asking for an opinion, and asking for clarification). Video topics were linked to the themes in their coursebook. Later, they were asked to complete surveys about using the online discussions, and after all online discussions were completed, a focus group was held in order to collect more feedback. Observations of the students interacting during the lessons, monitoring the online discussions, practicing for speaking exams in class, as well as speaking assessment scores were also used in data collection.

This report will outline the steps taken in conducting this action research, including detailed explanation of the materials used in the online discussions, how the online discussions were implemented, as well as how data was collected and analyzed. It will then summarize student outcomes and conclude with student and teacher perceptions.

Walker and White (2013) mention that the concept of ‘talk’ is not limited to spoken conversations. When applied to online environments, it takes on a broader meaning to include text-based conversations as a type of computer-mediated communication (CMC) (p. 106). In much of the literature, CMC as being supportive of oral language production has been more associated with synchronous technology like online chats or video-conferencing than asynchronous tools, but while asynchronous discussions generally encompass different characteristics, many of the principles that highlight synchronous CMC tools as being a springboard for students’ L2 verbal skills development can also be applied to asynchronous online discussion boards, albeit in a more delayed fashion.

When utilizing text-based CMC, time is on the side of the learner. Fluency often causes great anxiety in learners, and “being placed in a position where they are ‘on the spot’, and where they have to produce spoken language under time pressure is very stressful, especially as they often do not have native-speaker strategies for gaining time to think and plan…” (Walker and White, 2013, p. 38). However, in text-based discussions where time is plentiful, students are able to plan, edit, and correct their output based on their existing knowledge in what Krashen (1982) refers to as monitoring (Arnold, Ducate, and Youngs, 2011). Students can check their work before they submit it and self-repair – something students also do when speaking. By creating more opportunities for students to produce via asynchronous online discussions, students will become more comfortable with the language, thus their production skills can improve. deKeyser (2007) notes that producing output transforms declarative/explicit knowledge into procedural/implicit knowledge, which is an key factor in learning that also enhances fluency (as cited in Arnold, Ducate, and Youngs, 2011). In addition, this ability to “take your time” is beneficial when thinking about how Swain’s Output Hypothesis plays a role in text-based CMC. This hypothesis claims that “the act of producing language (speaking and writing) constitutes, under certain circumstances, part of the process of second language learning,” (Swain, 2005). In other words, learners must produce language in order to better process it – a sort of ‘practice makes perfect’. The more students produce, the better they will become at producing. When students in this study utilized online discussions, they were encouraged to use the functional language that they would also use in spoken discussions, and thus practiced expressing their ideas and interacting in this way. Additionally, with the help of video input and guiding questions, they also practiced thinking critically – a valuable skill that can be transferable to other areas. Johnson (2006) notes that “Asynchronous discussion facilitates student learning and higher-level thinking skills, perhaps due to the cognitive processing required in writing, time to reflect upon posted messages and consider written responses, and the public and permanent nature of online posting,” (p.51). In turn, students may be able to perform all of these skills with more speed as they practice them in online discussions, leading to the possibility of tapping into them during more spontaneous, spoken interactions.

Another key component of using asynchronous discussions is that students are also able to notice gaps in their linguistic knowledge – they realize they do not know how to say what they are intending to say. Swain (2005) claims that “under some circumstances, the activity of producing the target language may prompt second language learners to recognize consciously some of their linguistic problems,” (p. 474). This also relates to Schmidt’s (1990) notion of noticing in which students become aware of a new form or notice a linguistic gap (as cited in Arnold, Ducate, and Youngs, 2011). When students are conscious of these gaps, they can take measures to fix them by referring back to the input, negotiating meaning of the input, or asking for the input they need. This can especially be effective in online discussion forums where learners have access to the all of the posts and can reflect on them at any time. As such, they may notice other students’ mistakes and increase their awareness, which might “promote more syntactic processing and noticing gaps in linguistic knowledge,” (Arnold, Ducate, and Youngs, 2011, p. 27), that they can apply to all other skills, including speaking.

Asynchronous online discussion forums are also an ideal place for students to test their linguistic hypotheses. The Hypothesis Testing function of the Output Hypothesis claims that “output may sometimes be, from the learner’s perspective, a “trial run” reflecting their hypothesis of how to say (or write) their intent,” (Swain, 2005, p. 476). Students using online discussions can express themselves and interact in a way that seems less stressful or ‘high-stakes’ than in face-to-face interactions, which may lead to taking greater risks in their output. After feedback, students can modify their output and potentially improve their expressions and interactions in both a written and verbal way that stemmed from their “test drive” in the digital forums. Essentially, the online discussions may act as a type of ‘rehearsal’ for the real thing.

In addition to all this, knowing what is expected in certain pragmatic situations (discussions in this case) can help students perform better. Communicative Competence (Canale and Swain, 1980) combines “knowledge about the target language with an ability to use it effectively,” (Walker and White, 2013, p. 37). In this action research, the focus on functional language use within students’ posts as they express themselves and interact with other classmates helps them to understand what can be expected of discussions in English. It is impossible to focus on extra linguistic aspects of face-to-face verbal discussions or strategies involving spontaneity that can also be found in synchronous CMC, like using hesitation devices to gain time; however, asynchronous online discussions still give students the opportunity to use functional language common to discussions overall, focus on linguistic forms, as well as practice critical thinking to give more meaningful answers. Moreover, Goh and Burns (2012) proposed three speaking strategies learners can use to keep communication flowing: cognitive (finding ways around unknown vocabulary, like paraphrasing), metacognitive (monitoring language while speaking), and interaction (checking understanding, asking for clarification) strategies (as cited in Walker and White, 2013). I believe an analogy can be drawn here in that students can also take advantage of these strategies when participating in asynchronous online discussions. In practicing and developing these skills via a different outlet, they are further reinforced and feed back into students’ speaking performances and communicative competence. The online written discussions therefore aim to serve as a spring board from which they can improve their performance in spoken discussion tasks.

There are also other benefits of text-based CMC in supporting L2 learning. Not only is there often higher participation in CMC interactions, but participation appears to be equalized across learners, possibly due to lower anxiety levels than when interacting face-to-face (Leloup and Ponterio, 2003; Walker and White, 2013; Warschauer, 1996). It also helps students who are more likely to dominate face-to-face discussions to “learn to listen” to other participants (Warschauer, 1996). Multiple studies have shown that by working with synchronous and asynchronous CMC tools, “students are able to tap into their autonomy and progressively gain more independence and confidence,” (Arnold, Ducate, and Youngs, 2011, p. 35). In addition to all this, perceptions of both students and teachers are also important to consider in CMC-based tasks. In a survey by Branon and Essex (2001), educators found asynchronous discussions useful for “encouraging, in-depth, more thoughtful discussion…and allowing all students to respond to a topic,” while students in a survey by Dede and Kremer (1999) indicated that asynchronous discussions allowed for “richer, more inclusive types of interchange” (as cited in Johnson, 2006). Overall, asynchronous discussions are viewed as being an educational way to enhance learning outcomes (Johnson, 2006) and students generally have a positive attitude toward CMC use in L2 learning tasks (Leloup and Ponterio, 2003).

Context

The study was conducted at the English preparatory school of a university in Izmir, Turkey. The teacher met face-to-face with the students for four hours a week on Tuesdays and Thursdays for Listening and Speaking classes, thus the online discussions were meant to be supplemental to their in-class coursework. The study took place in the third module (out of four) of the academic year.

Design

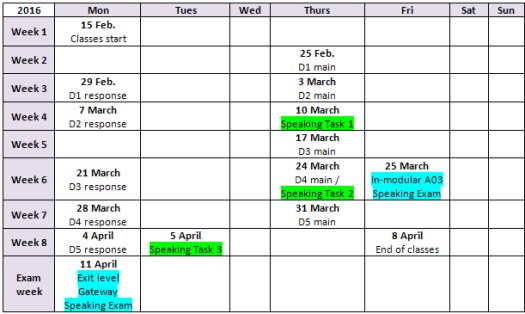

The online discussions were prepared with the unit themes of students’ listening and speaking coursebook in mind. There were a total of 5 discussions that spanned 8 weeks (see Appendix 1). Each unit was started and covered in depth, exposing students to both vocabulary and listening input as well as allowing them to adequately engage with the topic, before the correlating discussion was accessed. I chose to structure and scaffold the discussions very carefully because students are not familiar with this type of tool in their L2 learning. Additionally, structured discussions have been associated with higher levels of complex and critical thinking compared to unstructured discussions (Aviv et al., 2003, as cited in Johnson, 2006), so I kept this in mind when planning as well.

For each discussion, students were instructed to login to the Blackboard LMS, watch a short animated video, and respond to it by posting to the appropriate discussion board using the accompanying guided questions (see Appendix 2) and their own ideas. These questions aimed to promote critical thinking and were developed by the teacher under the influence of Bloom’s Taxonomy. This post was considered to be the students’ main post (75-100 word limit) and was to be posted on Thursdays before midnight. Then students were required to respond to at least one other person’s post. This was considered to be the students’ response post (50-75 word limit) and was to be posted on the following Monday before midnight so as to give students time to read and respond at the weekend. They were required to use functional language in all of their posts and were given a functional language sheet to refer to. Sample student posts for each discussion can be referred to in Appendix 4. Collective feedback was given in class via PowerPoint twice throughout the course.

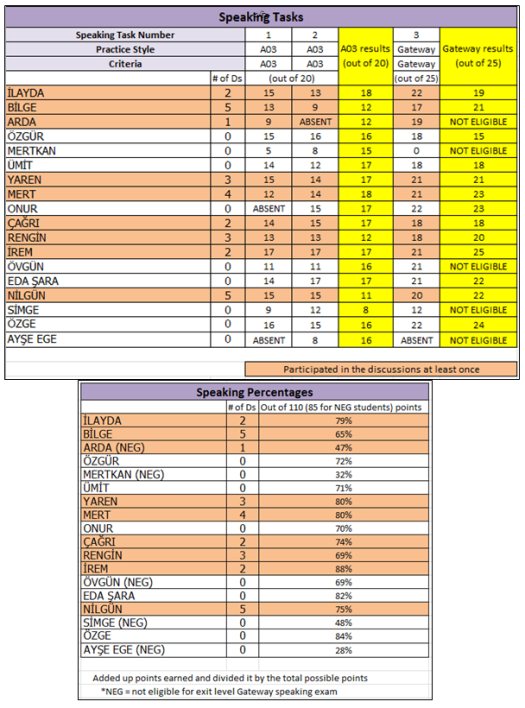

At three times during the course, in-class speaking tasks were given which simulated the ‘discussion’ section of either the students’ in-modular speaking A03 assessment (Speaking Tasks 1 and 2) or the exit level Gateway speaking exam (Speaking task 3) (see Appendix 3). The aim of this was to both monitor student progression and formally prepare them for the A03 and Gateway exams. The speaking task topics were not directly related to the online discussion topics, but the use of functional language requirement was the same.

Participants

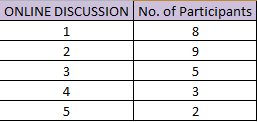

The participants were 18 intermediate (B1 exit level) learners of English at a university preparatory English school in Turkey. Students’ age ranged from 18 to about 23. Only nine students participated in the discussions at least once (see Appendix 10).

Materials

The online discussion tasks were produced to be used as supplemental tasks relating to Unit 1 (Nourishment), Unit 2 (Community), Unit 3 (Space) and Unit 4 (Scale), and Unit 5 (Success) of Bohlke, D., & Lockwood, R. B. (2013). Skillful Level 2: Listening and Speaking; Student's Book with Digibook access. Ismaning: Hueber Verlag. Students were given instructions and shown how to use the discussion board interface in the first week of the course.

Short animated videos relating to the themes mentioned above were used as multimedia input for the students to respond to for each online discussion. The videos included The Lesson of the Long Spoons from the One Human Family, Food for All campaign; a compilation video of three It’s Smarter to Travel in Groups commercials from Di Linj bus company; Skhizein by Jérémy Clapin (with English subtitles); Bridge by Ting Chian Tey; and Sweet Cocoon by a team of five French students of ESMA Montpellier (Ecole supérieure des métiers artistiques). Guiding questions were created for each video (see Appendix 2) for the students to use if they wished. A functional language sheet was also provided so the students could utilize it as they wrote their posts.

Three speaking tasks were also implemented throughout the course. They were created by the teacher in the likeness of the students’ in-modular A03 assessment and exit level Gateway speaking exam (see Appendix 3). The same functional language sheet mentioned above was also given to the students to refer to during the task.

Procedure

Discussion 1 (Nourishment)

The first discussion took place in weeks 2/3 and was related to the first unit in their coursebook, Nourishment. The video they were to watch and respond to was The Lesson of the Long Spoons video from the One Human Family, Food for All campaign, which was about one minute long. To do this, students signed on to their Blackboard accounts and accessed the Unit 1 (Nourishment) content folder. They followed three steps to complete the main post of the discussion assignment: (1) they accessed the instructions, (2) previewed the guiding questions (see Appendix 2) and watched the video, and (3) posted their reactions, ideas, or opinions by midnight on Thursday of week 2. For their response post, students had the weekend to read their classmates’ main posts and respond to at least one of them on the following Monday of week 3 before midnight. Students were encouraged to refer to the functional language sheet when writing their posts. With the exception of the dates and videos, each discussion followed the same procedure, so I will not list it again for the remainder of the procedural outline.

Dicsussion 2 (Community)

The second discussion occured in weeks 3/4 and correlated with the second unit of their coursebook, Community. The video they were required to respond to was a one and a half minute compilation video of three It’s Smarter to Travel in Groups commercials from Di Linj bus company. They wrote their main posts by midnight on Thursday of week 3 and wrote their response post on the following Monday of week 4 before midnight. The remainder of the procedure was the same as that of Discussion 1.

Speaking task 1

Speaking Task 1 was given in class on Thursday of week 4, with the students having had two full rounds of online discussions beforehand. The task was developed by the instructor in the likeness of the in-modular A03 speaking assessment (see Appendix 3), thus the in-modular A03 speaking assessment speaking criteria was referenced for this task. Students completed the task in pairs with only one pair speaking at a time. Students who were not speaking were instructed to listen to their classmates and give them a score based on a criteria provided by the teacher (1=needs improvement – 5=great) as a while-listening task. I gave feedback and tips during the task as needed if they struggled because this task was also their formal assessment practice, but I took note of this in the marks I gave. There was no discussion post due on the Thursday of this week so as to allow students to focus on the speaking task as well as for the sake of timing among the remaining units.

Discussion 3 (Space)

Discussion 3 took place in weeks 5/6 and corresponded with the unit on Space, the third unit of their coursebook. The video for this theme was Skhizein by Jérémy Clapin (with English subtitles), which was a bit different from the other videos used for the discussions. It was 13 minutes long and was very artsy in nature, leaving much open to interpretation. I took a risk in choosing this video despite its length in the hopes that it would lend itself to greater critical thinking practice and expose students to a different style of short film that they might never have considered otherwise. They wrote their main posts by midnight on Thursday of week 5 and wrote their response post on the following Monday of week 6 before midnight. The remainder of the procedure was the same as that of Discussions 1 and 2.

Speaking task 2

The second speaking task was the same as Speaking Task 1 and took place in class on Thursday of week 6. The same task and procedures were used in order to give students further practice for their in-modular A03 speaking assessment the next day. The topics were shuffled and students were given a different prompt from the one they had in Speaking Task 1.

Discussion 4 (Scale)

Discussion 4 was done is weeks 6/7 and was related to the theme of the fourth unit in the coursebook, Scale. Bridge by Ting Chian Tey was the video used for this task, which has a run time of about two and a half minutes. They wrote their main posts by midnight on Thursday of week 6 and wrote their response post on the following Monday of week 7 before midnight. The remainder of the procedure was the same as that of Discussions 1, 2, and 3.

Discussion 5 (Success)

The last discussion was held in weeks 7/8. The theme of the discussion was Success, which was the topic of the fifth unit of the students’ coursebook. The video for this discussion was six minute long was called Sweet Cocoon by a team of five French students of ESMA Montpellier (Ecole supérieure des métiers artistiques). They wrote their main posts by midnight on Thursday of week 7 and wrote their response post on the following Monday of week 8 before midnight. The remainder of the procedure was the same as that of all the other discussions.

Speaking task 3

Speaking Task 3 was on Tuesday of week 8, with the students having completed all of the online discussions beforehand. The task was developed by the instructor in the likeness of the exit level Gateway speaking exam (see Appendix 3), thus the exit level Gateway speaking exam speaking criteria was referenced for this task. There were two parts to this task and students discussed each of them in pairs with only one pair speaking at a time. Similar to Speaking Tasks 1 and 2, students who were not speaking were instructed to listen to their classmates and give them a score based on a criteria provided by the teacher (1=needs improvement – 5=great) as a while-listening task. Since this task was also being used as formal exam practice, I gave feedback and tips to the students as necessary if they struggled. However, this was again reflected in the grade they received as per the criteria.

Feedback

Feedback regarding the discussions was given twice during the course. The first feedback session consisted of a whole-class error correction activity via PowerPoint using collected errors from Discussions 1 and 2. It was implemented in week 4 after Discussion 2 was completed. The second feedback session was identical in nature but used errors from Discussions 3 and 4. It was done in week 7 after Discussion 4 finished. Unfortunately, there was no in-class feedback given for Discussion 5 due to time constraints.

Data was collected through the use of three instructor-created surveys that students completed immediately after the completion of Speaking Tasks 1 (Survey 1) and 2 (Survey 2) (see Appendix 6 and Appendix 7). Students were allowed to answer in either English or Turkish for all of the surveys. A focus group was also conducted in Turkish after Speaking Task 3 with the help of a Turkish-speaking Teacher Development Unit (TDU) member. In addition to these, I gathered data by means of monitoring the online discussions (sample student responses can be referred to in Appendix 4 and Appendix 8), observing classroom interactions and other exam practices, as well as using the scores from both the in-class Speaking Tasks and the students’ exam scores and percentages (in-modular A03 speaking assessment and the exit level Gateway speaking exam) (see Appendix 5). The number of participants in each of the online discussions was also kept in mind throughout the data collection and analysis processes (see Appendix 10).

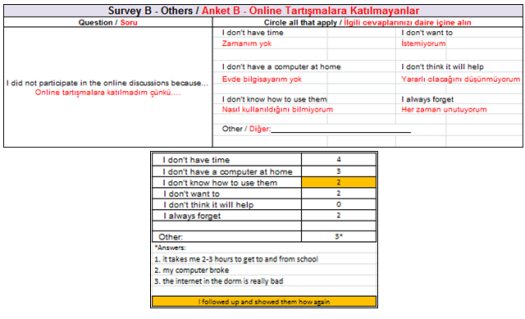

a. Survey 1

After the first speaking task in week 4, two different surveys were given. Survey A was given to nine students who had participated in the online discussions at least once, and Survey B was given to the seven students who had never participated. Two students were absent on the day the survey was administered, but they would have taken Survey B. Data has been analyzed and illustrated in Appendix 6.

b. Survey 2

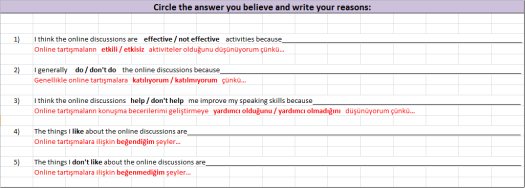

After Speaking Task 2 in week 6, 17 students were given an open-ended survey in which to write their own thoughts and opinions. One student was absent on the day the survey was given. Sample answers have been collated and included in Appendix 7.

c. Focus group

After Speaking Task 3 in week 8, a focus group was conducted in Turkish with six students (two students who participated in all of the discussions, two students who participated in some, and two students who never participated). A TDU member joined the focus group to take note of and translate their comments. Questions and sample student answers have been collated and included in Appendix 9.

d. In-class Speaking Tasks 1, 2, and 3 and Speaking Assessment and Exam Scores and Percentages

For each of the three in-class speaking tasks (see Appendix 3), the students were given a score according to the respective criteria (A03 or Gateway-related). The scores have been totaled and collated, and they are shown in Appendix 5. The students’ formal in-modular A03 speaking assessment and exit level Gateway speaking exam scores were also collected for analysis. It should be noted that these official test scores were given by a different instructor. They have been included in the chart in Appendix 5 as well. In addition to students’ scores, a percentage of these was taken to reflect students’ performance by adding up the total points earned and dividing it by the total points possible (110 points/85 points for the non-eligible Gateway students). This is also included in Appendix 5.

e. Monitoring discussions

The discussion forums, which consisted of student responses and interactions, were monitored by the teacher. Some of the language used by students in the discussions was also analyzed by the teacher (see Appendix 8).

a. Survey 1

The results in this survey show that the majority of the students who participated in the discussions up until that point felt positively about their experiences with it in terms of both their interactions with the other students and the effects the discussions may be having on their speaking skills. It is interesting to note that some students felt less positively about interacting with their classmates online as well as in integrating online coursework into their learning. This could be because of the class dynamics as well as generally being unfamiliar with using this type of technology for educational purposes.

Students who did not participate in the online discussions were instructed to circle all answers that applied as well as add any other reasons that were not listed. As shown in Appendix 6, students mainly claimed they did not have enough time or didn’t have access to a computer at home. Access to technology is an important aspect of digital coursework, so I was sure to remind students that they can use the computers on campus in the library to solve this issue. Two students felt they did not understand how to use the online discussions, and I followed up with them after the survey to show them how to do so again. Despite this, they never joined the discussions, perhaps for the other reasons they listed on their survey. Other reasons students listed for not participating included internet problems, long commuting times eating into their free time, as well as a broken computer at home. It’s interesting to note that none of the students circled the “I don’t think it will help” reason.

b. Survey 2

Survey 2 was more open-ended in nature, and most of the comments students gave were positive. In particular, students enjoyed the video selections and believed they were helpful in improving their productive, thinking, and interaction skills. They also believed the online discussions were good practice in general and for their exams. Areas of critique again included lack of time, feelings of worry about classmates reading their posts as well as negative feelings about being required to comment on others’ posts and the tasks being incorporated into their homework. There were very few negative comments overall, and it’s interesting to note that none of them were entirely specific to the online discussion tasks compared to other unrelated tasks done in the course. In other words, the negative feedback was similar to other negative feedback students sometimes give regarding other components of the course outside of this study.

c. Focus group

The focus group was also mostly positive, and I was happy that students felt comfortable with giving their honest answers, opinions, and criticisms during the meeting. The main things they liked about the online discussion tasks were again the videos as well as appreciating the in-class feedback and the help the online discussions gave towards preparing them for exams. The main things they disliked again included some of the procedural requirements, the fact that there was only one video for each discussion (no options), as well as potentially copying other students’ mistakes in the posts. One point that was also made during the focus group was that there were too many online platforms for the students to manage, which became confusing and resulted in the student ceasing participation in the online discussions. Overall, the students felt the tasks were helpful in improving various skills, including critical thinking and writing.

Interestingly, some students mentioned that they thought the online discussion tasks were more logical than the speaking homework they had every week which involved them recording themselves talking about a topic and uploading it onto Blackboard for teacher feedback. This was especially intriguing for me because it showed they saw how the asynchronous online discussions and in-class speaking tasks helped to support their speaking more than the video recording homework did. However, some students had trouble seeing the link between the online discussions and speaking skills while others felt face-to-face speaking practice would have been better, but this didn’t surprise me considering integrating technology into language practice in this way is still new to them. I was also not surprised to learn they felt they would have participated in the online discussions more if the tasks would have been worth more points. Nevertheless, I walked away from the focus group feeling like students had generally good experiences, but I also see where adjustments can be made in order to better accommodate the circumstances that are unique to this learning context.

d. In-class Speaking Tasks 1, 2, and 3 and Speaking Assessment and Exam Scores and Percentages

The in-class speaking scores showed varying results, with many of the scores either remaining constant or decreasing from Speaking Task 1 to Speaking Task 2 for those who had participated in the discussions. From Speaking Task 2 to the in-modular A03 speaking assessment, scores mostly increased for these students with a few decreasing. The same also holds true for those who did not participate in the online discussions. I believe this may be because the nature of in-class practice is different from that of exam conditions and students tend to not take the practices as seriously. Speaking Task 3 went well for the majority of students, and many of their scores were higher. For the exit level Gateway speaking exam, nearly all of the students who participated in the online discussions improved their scores in comparison to Speaking Task 3. All of the students were given a percentage to show their overall performance by adding up their total points earned and dividing it by the total points possible (110 points). Five students were not eligible to take the exit level Gateway exam, so they do not have a score to consider. For this reason, their percentages were taken out of 85 possible points. Overall, there was an increase in all of the students’ scores from the beginning to the end of the course, but the scores and percentages belonging to the students who participated in the online discussions appear steadier, as seen in Appendix 5.

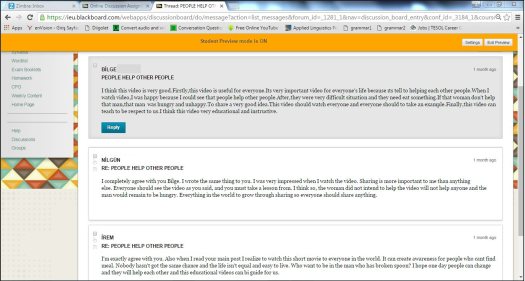

e. Monitoring Discussions – Student Interaction Sample

As illustrated in Appendix 8, a student interaction sample has been analyzed in regards to Goh and Burns’s (2012) speaking strategies. When looking at the squared sections, it can be seen that Rengin used paraphrasing and interactional language (confirming and agreeing) in her response to Yaren (cognitive and interaction strategies). It can also been seen when looking at the straight-underlined sections that she used deduction (Yaren never explicitly states that she was affected by the video but her last sentence helps Rengin to understand this) and paraphrasing to agree as interactional language (cognitive and interaction strategies). Lastly, looking at the squiggly-underlined section of Yaren’s post shows her use of circumlocution to deal with unknown vocabulary, as she was most likely looking for the words/phrases “fought (over)” or “changed (their ways)” (cognitive strategy). The metacognitive strategy is difficult to identify in text-based discussions since the student wrote the response out of class and thus unwitnessed by the teacher. Overall, this sample shows that, at least to some extent, students used Goh and Burn’s (2012) speaking strategies in their text-based discussion.

This study has shown that digital components are generally welcomed in the classroom by both the teacher and students and that they believe using asynchronous online discussions can be supportive of speaking skills in different ways. I think creating online discussion tasks that were well-structured and purposeful were of key importance in this study. However, given the points-oriented nature of students in this context, I also believe these tasks need to hold a greater weight in students’ overall score for the course if the tasks are to be effective to their full potential. I attribute this as being one of the main reasons for low student participation in the online discussion tasks of this study (see Appendix 10). It’s also important to remember that students may not be used to using technology like this for educational purposes, let alone in a language different from their native tongue, so it may take time for them to adapt. With all of this in mind, it might be a good idea to involve students more in deciding the procedural details, such as posting date requirements or word limits, so as to allow them to feel they have more ownership of the task and their own language learning. Encouraging students to do the online discussions by making the rationale explicit and reminding them of this throughout the course was essential, especially when students already felt overloaded by other coursework requirements. In the future and with the above adjustments, it may be worthwhile to repeat this study with multiple classes for comparison and further data collection. I also believe this study could be adapted to faculty English courses and would be very suitable for freshman English learning students, especially since they generally have fewer contact hours.

As my interests in CALL and TELL grow, conducting this action research has proved to be an incredibly intriguing and refreshing experience for me personally. I enjoyed exploring tasks and topics that are important to me and my students as well as the extent to which these can impact both my students’ learning and my own teaching practices. The investigative aspect of this research was the most enjoyable for me, as I liked interacting with my students on a more personal level to figure out how they feel about using technology as well as how they perceive the benefits of doing so. While every class is different, I see the allure of action research not only as being as a way to better understand my classroom, but also as a means of professional development in learning what works (or doesn’t work) in the classroom, why, and what role I should play in all of that as the instructor. In becoming more familiar with the ins and outs of action research, I am learning how to view the dynamics of my classroom from a different perspective, one that may work to suit the needs of my students in a more efficient way. I now have more questions, especially regarding the use of technology in language learning, and I see these as open doors that may lead to other research opportunities in the future.

In this study, I found that students generally felt positively about using asynchronous online discussions in their L2 learning and that they felt the use of such tech-based tasks helped them to develop their skills in English. While any type of correlation between the use of the asynchronous online discussions and students’ speaking performances cannot be clearly drawn, I do feel that the online discussion tasks helped the students develop this skill as well as the strategies students use when speaking. All elements of this study must be considered in light of the fact that there was a small study population and the participation rate among this population was low for various reasons, resulting in a relatively small data set. However, in my experience in conducting this research, I believe incorporating asynchronous online discussions into the coursework was beneficial for the students overall in supporting their speaking, writing, critical thinking, and technology-related skills and strategies. I would also consider doing so again in future classes with a few adjustments as mentioned in the Limitations and Implications section above. Regardless, it is clear that more research in this area is warranted in order to better understand the effects asynchronous online discussions can have on English preparatory students’ verbal skills development.

Arnold, N., Ducate, L., & Youngs, B. L. (2011). Linking language acquisition, CALL, and language

pedagogy. In N. Arnold & L. Ducate (Eds.), Present and future promises of CALL: From theory

and research to new directions in language teaching. San Marcos, TX: Computer Assisted

Language Instruction Consortium.

Johnson, G. (2006). Synchronous and asynchronous text-based CMC in educational contexts: A review

of the research. Techtrends, 50(4), 46-53.

Leloup, J.W., Ponterio, R. (2003). Second language education and technology: A review of the

research. In Eric Digest, EDO-FL, 03-11.

Swain, M. (2005) The output hypothesis: theory and research. In E.Hinkel (ed.), Handbook of research

in second language teaching and learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. 471–84.

Walker, A., & White, G. (2013). Technology enhanced language learning: Connecting theory and

practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Warschauer, M. (1996). Comparing face-to-face and electronic discussion in the second language

classroom. CALICO Journal, 13, 7-26.

APPENDIX 1

Discussion Dates, Speaking Task Dates, and Exam Dates

APPENDIX 2

Guiding Questions for the Discussions

D1

- What happens in the video?

- Is there a theme?

- What happens after the people start helping each other?

- What would happen if the people in the video didn't help each other?

- What is the main idea/message of the video?

- What life lesson does the video try to teach? Is it an effective video?

- Does the video relate to Unit 1 in Skillful (Nourishment)?

- Give an example of mental, physical, or emotional nourishment from the video.

- Does the video make you think about world problems? Give examples.

- How can people help each other in everyday life?

D2

- What happens in the video?

- What is the theme of the video?

- Are groups and communities the same? Why or why not?

- Why do the characters in the video travel in groups?

- What would happen if the characters in the video didn't travel in groups?

- Which group from the video did you like best? Why?

- What didn't you like about the video? Why?

- Are communities important? Why or why not?

- Give an example of how groups are beneficial in real life.

- Give an example of how groups can be bad in real life.

- What life lesson does the video try to teach? Is it an effective video?

- Does the video relate to Unit 2 in Skillful (Community)? Give an example.

D3

- What happens in the video?

- What is the theme of the video?

- How did Henry feel in the video? How do you know?

- What happens at the end of the video?

- Create a different ending to the story.

- What would you do if this happened to you?

- What did you like best about the video? Why?

- What didn't you like about the video? Why?

- What advice would you give to Henry if you could speak to him?

- What lesson has Henry learned about life?

- What do you think will happen next in the story?

- Does the video relate to Unit 3 in Skillful (Space)? Give an example.

D4

- What happens in the video?

- What is the theme of the video?

- How is the beginning of the video different from the end of the video? (think about scale)

- Did the larger animals' size help them cross the bridge? Why or why not?

- Did the smaller animals' size help them cross the bridge? Why or why not?

- Which animal would you prefer to be? Why?

- Why were the larger animals mean to the smaller animals?

- Why did the smaller animals untie part of the bridge?

- Do you think the smaller animals did the right thing? Why or why not?

- What lesson did the animals learn?

- How would you change the story?

- What did you like/not like about the video? Why?

- Does the video relate to Unit 4 in Skillful (Scale)? Give an example.

D5

- What happens in the video? - try to answer the other questions first

- What is the theme of the video? - try to answer the other questions first

- What adjectives describe the caterpillar? The other bugs? The bird?

- What did the other bugs do when they saw the caterpillar?

- How did the caterpillar feel in the video? How did the other bugs feel? How did the butterfly feel? Why?

- Compare the caterpillar at the beginning of the video to the butterfly at the end of the video.

- If you were one of the other bugs, would you stop to help the butterfly? Why or why not?

- How did the other bugs react at the end of the video? Why?

- How would you change the video? Would you change the ending?

- What did you like/not like about the video? Why?

- Was the butterfly's situation fair? Why or why not?

- Does the video relate to Unit 5 in Skillful (Success)? Give examples from the video.

Questions that were the same for each video:

- What is your first thought about the video?

- Is the video shocking, interesting, educational, etc.?

- How does the video make you feel?

- What kind of video is it (advertisement, movie clip, video blog, lecture, etc.)?

APPENDIX 3

Speaking Task Samples

Speaking Tasks 1 and 2

B

Student A: You think VIDEO GAMES ARE GOOD FOR CHILDREN. Discuss the topic using the ideas below or your own ideas.

• Educational

• Creativity

•

|

Student B: You think VIDEO GAMES ARE BAD FOR CHILDREN. Discuss the topic using the ideas below or your own ideas.

• Social skills

• Health problems

•

|

Speaking Task 3

A

Part 2: Prompted Talk– two minutes

The pictures show some different types of transportation that have changed our lives. Talk about the reasons people might choose each type of transportation.

Part 3: Discussion – two minutes

You are going to discuss some questions. Talk about each question together.

- What is the safest way to travel? Explain.

- Do you think the public transportation in Turkey is good? Explain.

APPENDIX 4

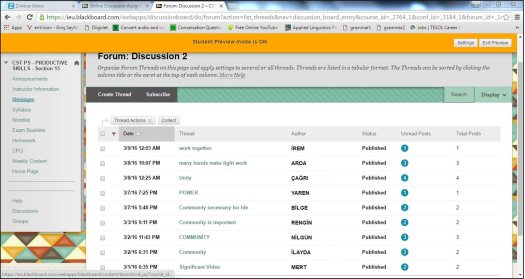

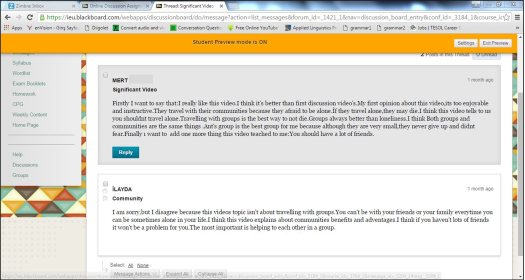

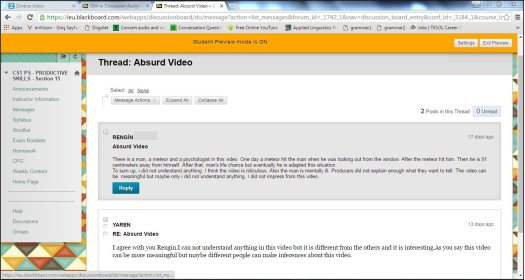

Discussion Screen Shots

*Students’ last names have been removed

Discussion Forum Sample – Discussion 2

Discussion 1 Students’ Response Sample

Discussion 2 Students’ Response Sample

Discussion 3 Students’ Response Sample

Discussion 4 Students’ Response Sample

Discussion 5 Students’ Response Sample

APPENDIX 5

Students’ Speaking Scores and Percentages for In-class Speaking Tasks, In-modular A03 Speaking Assessment, and Exit Level Gateway Speaking Exam

*Students’ last names have been removed

APPENDIX 6

Survey 1 (A and B) and Results

- Nine Students took Survey A

- The highlighted questions are about the online discussions and speaking skills while the unhighlighted questions are about student perceptions of online discussions overall.

1. Seven students took Survey B. Two students were absent, but they would have taken Survey B.

APPENDIX 7

Survey 2 and Sample Student Responses

Sample responses*:

Regarding question 1:

- The videos are attention grabbing.

- They encourage us to do research, which helps us improve ourselves.

- We learn how to give a response in daily life and unexpected situations.

- It could help our speaking skills.

- I can learn to speak English or writing.

- I think it improves my communication skills.

- We can improve writing.

Regarding question 2:

- We cannot speak English everywhere so I try to speak as much as possible.

- I don’t have enough time and when I go home I feel very tired.

Regarding question 3:

- They help to my think.

- I feel it has improved my speaking and writing skills when doing homework.

- Good way to study exams.

Regarding question 4:

- The selection of videos was really good.

- It improved my discussion skills.

- It is a good practice for exams.

Regarding question 5:

- We have to make comments.

- I feel ashamed of speaking in front of the class.

- It is given as homework.

*The Turkish responses have been translated and the English responses have been included directly.

APPENDIX 8

Student Interaction Sample

*Students’ last names have been removed

1. Each discussion board was turned into a .pdf for data collection purposes, and it is for this reason that the above sample has a different appearance from other samples in this paper.

APPENDIX 9

Discussion Group Questions Outline and Sample Student Responses

- What did you like most about the discussions?

- What did you like the least about the discussions?

- Why did you stop using the discussions?

- Why didn't you use the discussions at all?

- Would you have used the discussions more if they had been worth more points?

- Do you think the discussions helped develop any of your skills? Which ones?

- What would you change about the discussions to make them better?

Sample responses*:

Regarding question 1:

- It’s helpful for the exams.

- The videos are good and attention grabbing.

- Receiving feedback in another good point.

Regarding question 2:

- We copy our friends’ mistakes which doesn’t help our English.

- There is only one video, not many options.

- Setting word limits is not a good idea.

Regarding question 3:

- There is no specific reason.

- There are too many online platforms (Oasis, Blackboard, MyEnglishLab) and it’s confusing.

- I got bored because it was homework. I have exams to worry about, not this.

Regarding question 4:

- I didn’t use the discussions as all because speaking face-to-face is better.

- It is assigned as homework which is why I don’t want to do it.

Regarding question 5:

- We would definitely join the online discussions more if we got more points for them.

- The online discussions are more logical than the weekly video recording homework [the video recording homework was a homework assignment that is standard across the curriculum and done in every class in every level]

Regarding question 6:

- They encouraged us to think critically.

- I think it generally improved my writing.

- I don’t see the link between the online discussions and my speaking skills.

Regarding question 7:

- There shouldn’t be a time limit.

- It shouldn’t be every week.

- The time span between videos and response should be longer

*All responses were given in Turkish and have been translated here.

APPENDIX 10

Discussion Participation Summary

Please check the Practical Uses of Technology in the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical Uses of Mobile Technology in the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|