A Didactic Activity: Humour as a Problem-solving Strategy in an Intercultural Perspective

Giampaolo Poletto

Giampaolo Poletto, is a Doctoral Candidate, Doctoral School of Linguistics, University of Pécs, Hungary. E-mail: g.poletto@yahoo.it

Menu

Introduction

"What do you do/say if ...?"

"What do you do/say if ... in Italy?"

Conclusion

A theoretical appendix

The role and function of humor in an educational environment

Problem-solving communicative mechanisms

Bibliographical references

Introduction

My paper empirically and concisely draws on the use of humor as a problem-solving strategy, in an intercultural perspective, with the aim to design a didactic activity for foreign/second language learners of Italian. The theoretical background is exposed in the appendix, together with the bibliographical references.

With reference to second/foreign language learning and teaching, the use of humor has benefits and backdraws, in terms of class management, linguistic and interactional skills, communicative competence. Intercultural competence implies cultural diversity and sensitivity, above all when linguistic humor is involved. Problem-solving devices are communicational strategies. I therefore present authentic documents, that is samples from lessons to classes of foreign language learners of Italian, where I show the relation between interculturality and communicational strategies of problem-solving, in the concrete perspective of the routine language teaching practice. Finally, I tie the net and expose a situation- and context-based groupwork activity, in five steps, which specifically and purposedly implies the use of humor as a problem-solving device, in the framework of communication strategies which lay the emphasis on intercultural aspects. Addressees are differently proficient second/foreign language students of Italian. The aim is to show how humor may work in a language classroom as a facilitator, which contributes both to create a positive and collaborative environment and implement intercultural sensitivity and L2 communicative competence.

"What do you do/say if ...?"

The following set of sample lessons display the interrelation between aspects of L2 communicative and intercultural competence in the concrete perspective of the routine language teaching practice. The role and function of humor and of problem-solving devices happen to linger in the background. They are specifically targeted in the next section.

In the light of a task-oriented activity in a language class, a reply to the question in the title is solicited by the teacher. Learners are proposed a document in the target language functional to the envisionment of a clearly recognizable and shared situational context. It works as a stimulus to elicit their participation in terms of L2 production and cross-cultural confrontation. Learners access specific cultural traits in L2 which emerge during a lesson, even unpredictably, in relation to the response and sensitivity of a specific group. In the foreground there are here aspects of L2 communicative and intercultural competence. Humor, as a trigger of solving mechanisms as well as of intercultural sensitivity, can be exploited but it is not directly targeted in the below samples.

Examples are taken from my teaching experience as an Italian native teacher with differently proficient Hungarian foreign learners of Italian of different classes and schools from 14 to 18. The lesson implies: a co-constructed introduction; the accomplishment of the given task by the learners, intertwined with cross-cultural observations. Periods are one to two, of forty-five minutes each. Learners are assumed to have been submitted the didactic proposals in the below standard form. Documents are authentic in that the setting is always the Italian environment.

The question in the title ties the samples. During the lesson, it represents a teacher's communicational starting move and strategy to assess: the comprehensibility of the input; the internalization of the stimulus, in other words the given situational context; learners' interactional skills; the communicational strategies enacted in the L2. In this set of samples, learners are not requested to operate a shift from their own to the Italian environment. For the sake of a more immediate accessibility and response, they are rather requested to embed the given situation in a context which is familiar to them.

The situational content and the cross-cultural observations are calibrated on the specific kind of environment of the learners, in my case a town in Hungary, Pécs. With the aim to foster a cross-cultural confrontation, in the wider framework of promoting the learners' intercultural sensitivity, the teacher is to take into account aspects in both the target and the arrival culture. Thus, he/she can manage to identify some aspects blatantly too distant, some others somehow comparable, some definitely similar, and avoid the first group, if possible. The acknowledgement of which is which may be a product of a lesson, not just a prerequisite, as the final remark of the description of each sample intends to stress.

Also the second set of situations is displayed through an excerpt from an Italian film. Aman gets up from his seat on a bus when he sees the ticket-inspector, who has just got on from the rear door, has immediately spotted and makes after him. An old passenger pokes his nose and acts as a witness of the conversation between the two. The younger passenger has no ticket and enacts a series of communicational strategies to get away with it without being fined, which proves successful in the end. The scene takes place first on a bus, then in the open, on a street in a town, probably Rome. The sequences are finally reviewed and reconstructed, through an informative sheet supplied to the students. The conversational exchanges are not so relevant to the understanding of the content.

Learners can play three roles. The set is familiar because they often use the bus, to go to school, home, for leisure, as passengers, with or without the ticket, and witnesses. As emerged from a first oral exchange with them, it is more difficult for them to personify the conductor, who turns out to be generally unsympathetic, both on an Italian and a Hungarian bus, from the shared perspective of the protagonist of the clip, the teacher, when he/she used to be a student, the actual learners. The question "What do you do/say if ...?" is posed to address the unique situational context of a passenger without the ticket, from three viewpoints: the passenger's; a witness's; the conductor's.

The focus is on goal-oriented communicational strategies, such as taking time, avoidance, using irony, taking and keeping the floor, mostly deployed by the passenger who is intentionally disrespectful. The passenger may admit or not that he has got no ticket; the conductor may be strict or comprehensive; the witness may be a nose-poker or 'indifferent'. Students have actually declared that they would not give in the transgressor even if they knew about him/her in the above situation.

Italian traits to be emphasized are: the procedure and lexicon connected to the acquisition and use of a ticket; the efficiency of buses, notoriously not on time; the traffic in town, which is a problem in Italy, above all in the peak hours, for cities are mostly historical; the attitude of car drivers, who are nervous and do not hide their tension; the behaviour of passengers on the bus, where the rear seats are for the noisiest ones; the attitude towards ticket-inspectors, who tend to be despised. I have learnt that in Pécs they are two, instead of one, as in Italy: a woman and a man, who get on the bus simultaneously from two different doors, are known to and sort of feared by everybody. I have also learnt that buses are more puctual, car circulation has rapidly increased in town in the late years, drivers are almost as bad tempered, passengers are of all sorts.

A public place as the 'osteria' in Italy is a kind of restaurant which used to serve genuine local food in a rustic environment and was not expensive. A leaflet in Italian with pictures and captions advertises a restaurant whose name opens with the word 'Osteria' in capital letter. The owners have just partly modernized an old country house and offer a menu with local dishes as far as pizza-pie, in a site of interest, by the Lake of Garda. Prices are variable and a wide range of costumers is addressed: employees during the lunch break; managers or agents passing by and in the need for a place where to eat and discuss work issues; youngsters or couples or families with children who want to have a pizza or a dinner out; families, relatives and/or just friends gathering for a celebration.

Learners are given an explanation and are requested to proceed in two steps: to list a set of up to ten questions which arise from the exam of the advertisement, supplied in photocopy, and concern the presentation of the 'Osteria'; to use the same and/or other questions to reply and present an alike Hungarian restaurant, pizzeria, 'csarda' - the Hungarian for 'osteria' - which they have heard of or go to. They must say why it is worth going, too. Questions - in Italian, like the answers, here quite literally translated - are of the kind: What is the name of the place? Where is it located? What kind of food do they serve? Can you make some examples (of how some of them are)?, and so on. Targets are functions such as acquiring and providing information on a given topic, in this case providing a motivated advice on a place where you can eat meals, referred to through the overarching question: 'What do you say if you have to talk about a place where to eat to a friend or somebody else asking for it?'.

Italian cultural traits relate to: traditional local dishes, with some examples; the role, collocation and features of the 'osteria'; the peculiarities of the location, in this case the Lake of Garda; the procedures of booking a seat, paying the services provided and being given a receipt; customers and the organization of work; customers and parties or celebrations, in particular family celebrations connected to sacraments, just like lunches on the occasion of someone's baptism, communion, confirmation, wedding. In Hungary restaurants do not have a closing day, just like in Italy, therefore a question about that is groundless. A word just like 'banchetto' - banquet - has an almost omophone lexical item with a very different use. Finally, occasions for celebrations are slightly different; for instance, there are class meetings, which take place regularly, periodically and traditionally throughout and after the four years of high school.

"What do you do/say if ... in Italy?"

Addressees can be beginners to advanced differently proficient high school second or foreign language learners of Italian. The teacher will evaluate to which extent the goal-oriented proposal is practicable. This groupwork in the below standard form covers the length of two periods of forty-five minutes each. A set of ten routine situational contexts in Italian is given. The setting is assumed to be located in Italy. Therefore, the question in the title of the previous section now reads: "What do you do/say if ... in Italy?"

Each group chooses five and work to produce two solutions in their L2: one non-humorous, one humorous. What is under scrutiny is the effectiveness and correctness of the solutions, presented in the form of a short conversational exchange between a person in need for help and a friend in support. The aim is to elicit and raise the learners' interactional skills, L2 communicative competence and intercultural competence.

The viability of the proposed solutions represents the outcome of the communication strategy enacted by the learner in the L2, with the aim to successfully face a practical and concrete problematic instance, in a contextualized situation, which is recognizable and familiar to the learner, in terms of world knowledge and personal experience, but occurs in a linguistically and culturally different setting. Humor is an integral part of the activity and contributes in two directions.

On the one hand, it fosters the creation of a collaborative environment, which solicits the learners' sensitivity both to linguistic and intercultural aspects emerging during the accomplishment of the activity. On the other hand, it provides a way other than serious discourse to overcome a doublefold problem: how learners can say something in L2, with respect to their proficiency; how they can say something in L2 which is appropriate to the given situational context, that is to help a person in need and to create rapport.

There is a possible communication impairment, which derives from the learners' lack of knowledge in terms of language code, sociocultural constraints and rules, discourse rules. The learner is to take risks, whether she/he chooses to exploit humor or seriousness as a problem-solving device in L2. The learner is to resort to her/his strategic competence in L1 and L2 in order to activate a suitable problem-solving mechanism. The presence of a humorous option emphasizes it and makes it more binding.

There is the concrete situation of a person, supposedly an Italian native, who seeks for help, and urges a way out of his/her factual impairment. The humorous solution is to ease it and create rapport, which directly ties to aspects of personal and intercultural sensitivity, given the use of the learner's L2 in an L2 setting. The learner is again to resort to her/his background knowledge and competence, the more when humor triggers the solving mechanisms.

The presence of a humorous discursive option widens the perspective of the evaluation. The teacher is to take into account unintended and unsuccessful humorous acts, together with the set of communication strategies verbally enacted by the learners. Furthermore, it is worth reminding that the verbalised solution is humorous exclusively in the perspective of the group. What matters is that the message is comprehensible and meets the requirement of providing a suitable answer to the given question.

The way it is humorous in the particular context of the group, it may be in the given situation of the two interactants, at an interpersonal level. The humorous effect may not arise from the utterance as a verbal act in itself, rather can be determined by a series of contextual elements, which provide the utterance with clues for an additional and alternative interpretation. Such clues are accessible to the interactants who, for instance, can relax and express their feeling through a smile or a laughter. If this effect is shared by the group and it is enough for the members to label the utterance as humorous, that utterance represents their humorous solution, or intended humorous act.

Conclusively, in the case of intended humorous acts, the teacher has one further possiblity of laying the stress on linguistic, strategic and cultural implications. Linguistic aspects directly refer to L2 language assessment. Strategic elements relate to L2 communicative competence. Cultural traits tie to intercultural sensitivity. Humor is thus a tool and a resource.

The teacher introduces the activity, focusing on personal mishaps and the way to successfully tackle them, eventually using humor. Examples are from his/her or the pupils' direct experience or from other sources. There are five steps: the recognition of the given instances; the elaboration of two solutions; their exposition by each group; the discussion; a cross-cultural confrontation. The teacher monitors each phase and assists each group, can use different media, and also opt for recording audio or video the learners' performances, to make use of this live material for reinforcement of listening and talking or reflecting on communication strategies.

The concrete model of adolescent student in the following list of ten situations are my Hungarian high school foreign learners of Italian. Teachers are free to monitor and collect information on which are the most suitable ones for their class and adapt, modify or even change some. A genderless 'you' refers to a person in a stall, due to a face-challenging dramatic instance, tiny or more consistent. The supportive friend is assumed to be there and witness the events. Each group is free to give a precuse identity to the protagonists and add some background information, on their feelings, reasonings, etc.

Each group analyses the scenario and exposes the solutions, motivating their assumed effectiveness. They can even stage them. Solutions are verbalized in an oral and written form, in Italian, and basically answers the question: 'What do you do/say to help if your friend is in the given situation in Italy?' The instances to overcome are here reported in English, for the sake of understandability and conciseness - not without a hint at their transferability in other languages, that is at their use in a language classroom where the learners' L2 is not Italian.

1. You lent your mobile to a friend, who has used up almost all of your credit, as you discover

when you get it back.

2. While you walking on the footpath, your dress gets spattered with water by a car passing in a

puddle.

3. You dress up and arrive at your friend's for a party, but on the wrong day.

4. At your party a friend whom you have invited, to everybody's knowledge, has not turned up.

5. You rush to catch the bus and try to get the driver's attention, but when you are close the

doors shut and it leaves.

6. You have misdialed the number and sent your text message to the wrong person, whom you

know.

7. You ask your friend out to go to your favourite restaurant, get there, go in and see that all

tables are booked.

8. While you are walking with your friends along the main street, you stumble and (almost) fall

to the ground.

9. With no fear you get close to and stretch your hand towards your friend's dog, which almost

bites you.

10. Although the waiter has got your order, too, everybody has been served their dish but you.

Now, let me draw on an example, given this situation: 'Back home after an evening out you realize you left the keys inside, where everybody is sleeping'. After selecting it, the group makes a recognition, adding further contextual information to set the frame, such as: the boy or girl often stays out until late; his/her mother has a very sound sleep; the bell is out of order; etc. Solutions are uttered and detailed, during the exposition. This is the phase when the observation of peers' use of problem-solving devices allows to inductively focus on their communication strategies.

'Be my guest tonight!' and 'You wanted to stay out at night, didn't you?', whether humorous or not, in the group's perspective, infer the interactants are close friends and their houses are within a few minutes walk. 'Well, let's ring the bell, shall we?' and 'Wake them up!', whether humorous or not, opt for the return, instead, and reveal two different attitudes towards the people who are sleeping in the house. They imply an evaluation of their impact in terms of face, with respect of the interpersonal relation between helper and helped and between them and the house inhabitants. One interpretation is that the latter may be extremely offensive. Another is that, whether polite or not, the content of both is shared by the interactants, who are supposed to know each other very well. As to the latter, the group is to provide an explanation of the disrespect they appear to show. These are issues to examine during the discussion and when intercultural aspects are pointed out.

In an intercultural perspective, various elements emerge. A solution such as 'Go in from the window!' is problematic. As a matter of fact, in Hungary a double window system is widespread, thus such a hypothesis is unlikely to be formulated. That may lead to a reflection on the kind of house where the friend lives and its collocation, for instance. It can be in a block of flats in the center or the outskirts of a big or a small city, which is not the same; or a detached house in a row in a smalltown or in the country, where it is isolated. The garden is usually also cultivated in Hungary, whereas in Italy there are two types, one for fruits and vegetables, another for trees and flowers. It is also interesting to discuss a topic such as staying out until late, with reference to the lifestyle of Italian youngsters, who are assumed to be peers to the learners; the relevance of the setting, as living in a smalltown is different from living in a city; the role and attitudes of parents, to stress on differences and affinities.

The teacher leads the discussion and as a native Italian provides the learners with a way to access their L2 culture. Thus, he/she can resort to humor in relation to his/her knowledge, both to keep a collaborative environment and, above all, to vehiculate culturally relevant information in a humorous form. A joke, a proverb, a way of saying, an anecdote can offer the opportunity of sheding light on stereotypical behaviours, for instance. The aim is not to arise laughter, which can be impeded to the learners for lack of linguistic and cultural knowledge, rather to effectively and briefly communicate a content of cultural relevance which is to be explained. Humor is again a tool and a resource.

With relation to L2 communicative competence, it can be emphasized, for instance, the preferred use of the imperative, of a direct or indirect mode of communication, of an invitation or an order, of polite questions, of longer or shorter utterances. In terms of language assessment, the aspects of fluency and errors are to focus on. Problem-solving devices are enacted as communication strategies, of adjustment, achievement, or time gaining. They consist in a literal translation, code-switching, foreignizing, if related to the learner's existing linguistic knowledge; paraphrasing, use of semantically related terms or word coinage, if tied to his/her L2 knowledge.

Conclusion

I have attempted to work out a practical approach towards the didactic use of humor in a language class as a problem-solving strategy, in an intercultural perspective. The focus has gradually shifted to the role and function of humor in an educational environment, with reference to second/foreign language learning and teaching, in relation to problem-solving devices as communication strategies and intercultural competence.

The perspective is the routine language teaching practice. First, I have described a set of lessons to Hungarian foreign language learners of Italian. Then, I have outlined a sample didactic activity, which particularly aims to reinforce the learners' interactional skills, L2 communicative competence and intercultural sensitivity.

The task-based and goal-oriented groupwork activity unfolds around the elaboration of solutions to a set of situated problematic instances. One solution implies the strategic use of humor, which contributes in two directions. It helps create a collaborative environment in the language classroom; it provides a way alternative to serious discourse to solve a doublefold problematic instance: how to say something in L2, in relation to the learners' degree of proficiency; how to say something in L2 which is appropriate to the given situational context, that is to concretely assist a person in need and to create rapport.

Humor turns out to have the role and function of a tool and a resource, which supports the management of the language classroom, during the accomplishment of a didactic activity; triggers problem-solving mechanisms in the context of L2 communication, which is the task of a context-based activity; sheds light on cultural aspects in L2, which implies the use of L2 intercultural competence and fosters intercultural sensitivity.

A theoretical appendix

The role and function of humor in an educational environment

Research on humor and its functioning in language has recently given proper attention to aspects of language such as humorous communication, cognitive processes and communicative strategies involved in humorous communication, which are relevant to human interaction (Attardo & Raskin 1991; Norrick 2003), given the pervasiveness of humor. It is a tool for achieving various communicational goals and fulfilling relational functions, which aims to convey relevant meanings communicated in a non-humorous mode (Dynel-Buczkowska, 2006).

The speaker invariably have underlying goals other than amusing the hearer. In relation to Brown and Levinson's classification (1987), verbalisations of conversational humour can be either face-threatening acts aimed at social control (denigration or exclusion from a social group) or face-saving acts (bonding, rapport-enhancement and mitigation). In an educational context, such as the language classroom, the former are to be prevented, the latter enhanced, to which both the teacher and the learner are committed.

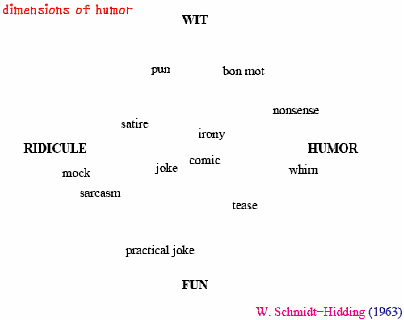

The more on considering its multidimensionality, which can be displayed as follows:

Valeri & Genovesi (1973) acknowledge its multidimensionality and set a frame where the social, cognitive and educational aspects of humor are tightly intertwined. Its main elements are: contrast, immediacy, splitting, oddness, disintegration, detached and not projective participation. In the dynamics of socialization, humor implies taking or leaving the floor; protecting or attacking a member of a group or a group; conforming or disrupting; presenting a self for ratification or frustrating semebody else's. In a cognitive perspective, humor is tightly connected to creativity and the human development: it involves the use of the divergent thinking (Bruner, 1969) and of both emispheres (Gardner, 1983; Danesi, 2003); it is produced and received in a diverse way according to the age; it triggers processes of association and dissociation, it requires immediacy in analysis, synthesis and judgement; it is tied to playfulness.

Emphasizing Kinginger's view of the classroom as an interactive setting (2000), Sullivan (2000) parallels the role of humor in the social practice of everyday conversation and of the classroom interaction. She refers to storytelling and wordplay, in particular, and points out how they are strategies which create rapport, help bring about a relaxing atmosphere (Mahovec, 1988), allow the speaker to present a self for ratification by other participants (Goffman, 1981). In the same line of thought, Davies (2003) shows how humor fosters the 'conversational involvement' (Tannen, 1989) and reinforces collaborative skills. As interactants, learners establish a common ground and strategically orient toward solidarity and affiliation the activity of joke telling and understanding, as any form of humor deeply embedded in cultural context (Apte, 1985).

Humour help establish a positive learning environment (Sever & Ungar, 1997) and benefits the relationship between teacher and students (Pollak & Freda, 1997). As a teaching strategy, alleged benefits include the promotion of understanding, increased attention and interest, motivation towards learning, improved attitudes, productivity, creativity and divergent thinking (Parrott, 1994). It is useful as a device for gaining and maintaining attention and interest, in that it contributes to decrease academic stress and anxiety, boredom and disruptive behaviour. Ziv (1979) reports results which indicate that if the introduction of a concept is followed by a humorous example, and then an explanation of the concept is provided, test performance is improved. Along with that, humor has been proved to serve to illustrate, reinforce and make more comprehensible the material being taught (Powell & Andresen, 1985).

When a teacher uses humour and is able to stimulate the students to laugh or smile, then at least to that extent the teacher knows that the students have been engaged with their response and has provided one form of feedback (Ziegler, 1998). The use of humor has been acknowledged to raise students' motivation in the language classroom (Medgyes, 2002) and to be an important tool with reference to a foreign culture, in order to reach higher social competence (Zajdman, 1995). As a self-effacing-behavior (Provine, 2000), humor is signalled for the importance in the affective environment of second language teaching (Kristmanson, 2000), where it has been shown to have positive effects (Berk, 2000).

Its overuse in teaching, particularly of verbal humor, has an element of risk. By its very nature, humour may seem antithetical to the seriousness that usually characterises teaching (Powell & Andresen, 1985). Experience of verbal humour suggests that delivery is a real skill. Not all students will be attentive and understand, while there is the risk of offending through misunderstanding with any joke being perceived as a source of ridicule, sarcasm or as being racist or sexist. Chiasson suggests how, in the second language classroom, the use of humor by the teacher should be spontaneous, fit his/her personality, not be private or exclusive of other learners, be an integral part of the class (2002).

In a collaborative language classroom environment, learners can take risks and express themselves in their foreign/second language in class, without facing ridicule or criticism; on the contrary, they are praised for their effort. Also the production and appreciation of the intended or unintended humor involved in the learner's expression actually ties to the learner's L2 communicative competence (see Canale & Swain, 1980; Canale, 1983 and references therein).

Their eventual errors, which may arise laughter, as unintended verbal humor, provide the teacher with a very important piece of information. Errors factually contribute to focus on a specific linguistic item, in the perspective of language assessment, with regard to transfer errors, overgeneralization, avoidance, idiomatic, idiosyncratic errors, for instance (Fillmore, 1979; Kerper Mora, 2003). As Norris points out (1992), the recognition and elimination of common errors can foster the processing of language stimulus to a deep level of memory, where the possibility of long-term or permanent retention is increased (Stevick, 1982).

The more if humor is used and has the effect of lowering the learner's affective filters (Krashen, 1982), that is, if the teacher is able to immediately, appropriately and constructively work to correct the error, by addressing the whole class. The above effect and the involvement of the entire group may be obtained through an intended and successful act of verbal humor by the learner. In terms of language assessment, what is emphasized is the learner's fluency in talking, use of vocabulary and syntax, knowing the rules, creativity with language (Fillmore, 1979; Kerper Mora, 2003). The classroom environment is benefited, provided that the humorous utterance is supportive of the ongoing didactic activity. There are actually risks.

The reaction of the class to an act of unintended humor may turn out to be embarrasing for the learner, who was seriously committed to his/her production in L2. It is extremely important that the teacher acts as a mediator and is able to exert control and properly manage the situation, which is not to be to the detriment of the learner's possibility of interaction. On the other hand, it has a disruptive effect when a student intentionally breaks in during the period with a humorous remark, exclusively for face recognition in front of the group; or else, when learners' humorous turns are between themselves and disengage from what the teacher is doing.

In conclusion, given its multidimensionality and pervasiveness in communication, where it turns out to be a tool for achieving purposes other than arising laughter, humor can be profitably exploited in an educational context and in second/foreign language learning and teaching, in the framework of active, joint and participated schooling and class management. Benefits for the learner are emphasized, in terms of linguistic and collaborative skills and L2 communicative competence.

Boundaries are to be set: its pedagogical value goes hand in hand with the teacher's educational values; satire and irony are dispreferred; mere entertainement is not to be the target; to create rapport is not to take and keep the floor either in a frustrating and authoritarian way, by the teacher, or aggressively and disruptively, by the learner.

Humor and intercultural competence

In an educational framework, Ziesing (on line) emphasizes the importance of cultural literacy for achieving fluency in the target language, at the monolingual, basic, advanced, professional, fluent stage. Literacy is a social skill, where cultural and cross-linguistic concepts add to the traditional skills involved in reading and writing but also including (Snow, 1992; Barfield et al., 1998). Competences related to cultural concepts are part of literacy development. As a tool, communicative competence in a foreign language: serves students in the target language; is consistent with their general world knowledge; sheds light on the acquisition of cultural sensitivity. The understanding of humor certainly plays a role in this process.

Culture and language are deeply interwoven with humor. Humor is context and culture-bound, thus the most difficult feature of another culture (Solomon, 1997). In that perspective, it reflects and is a marker of cultural diversity. As Rappoport emphasizes (2002), depending on its contexts, humor can be offensive - that is aimed at ridicule of an ethnic group - or it can be defensive - that is aimed at protecting a group from ridicule - or it can be both at the same time. Veatch (1998) acknowledges how language is implicated in humor, from lexical ambiguity to linguistic ill-formedness or stigmatized forms, from dialect features to linguistic arguments. What sounds unusual or incongruous to the hearer arises its laughter, including grammatical errors and differences.

As a component of culture, humor is a resource which can be exploited among the techniques providing an access to another culture to the learner, in that it sheds light on cross-cultural differences (Omaggio, 1986; Seelye, 1993). According to Paksoy (on line), then, understanding humor corresponds to the highest level of language competence, or native fluency. Understanding humor is an integral part of fluency, in that what requires is a number of cultural reference points, including history, customs, games, religions, current events, taboos, kinship structures, traditions and more, in other words cultural literacy.

As to its relation with interculture, Fantini (2000), along with Kealey (1990) and Kohls (1979), remarks the presence of the sense of humor among the most commonly mentioned descriptors of intercultural traits. Different levels of intercultural competence can be achieved, from the educational traveler to the sojourner, from the professional to the intercultural/multicultural specialist. Awareness, attitude, skills, knowledge and proficiency in the L2 are the dimensions which are acquired in a developmental process, often lifelong and becoming, rather than complete.

In this perspective, various models of intercultural sensitivity have been elaborated, each with a sequence of stages of development. According to Bennett's model (1993), for instance, the experience of difference basically characterizes its dynamics, in a scalar transition from ethnocentric to ethnorelative stages, from denial, defense, minimization, to acceptance, adaptation, integration. Humor is involved in the last two. On the one hand, with reference to the content, through which the educator supports the learner, appreciation of humor is among the advanced cultural topics which require intercultural empathy. On the other hand, a culturally sensitive sense of humor is among the stage-appropriate intercultural skills of the learner which are to be reinforced and promoted.

In conclusion, given its ties with language and culture, the role and function of humor, when interlanguage and interculture are targeted, are double. On the one hand, humor may work as a marker of diversity, distance, inaccessibility. Ethnic jokes based on stereotypes and recounted by outsiders of the targeted community are an example. On the other, it may foster and strengthen an intercommunication between linguistically and culturally autonomous and different identities, because humor appreciation, both in the construction and in the production phase, implies sensitivity, that is a positive attitude towards cultural otherness.

Problem-solving communicative mechanisms

In the language classroom, learners perceive and access new information through conversation (Cazden, 2001). Through collaborative discussion, the learner is more involved to participate, discover and negotiate meaning, and reduces fear to lose face (Varonis & Gass, 1985). Teacher-student and peer interactions provide what has been labelled as a scaffolded help, using Donato's metaphor (1994), which refers to the ability of learners to perform beyond their own current capabilities, towards the creation of the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978). Through groupwork, differently proficient learners and their interactional skills benefit from participation (Antón, 1999; Shea 1994), provided that grouping is done appropriately (Cameron & Epling, 1989).

Learners are thus assumed to be in the conditions to attempt to produce in their L2, and make use of problem-solving devices. As Manchón underlines (2000), they are communication strategies, which counteract the imbalance between ends and means typical of L2 learners' productive use of language. Due to missing or inaccessible knowledge in the L2, there may be a communication impairment for the learner, who resorts to existing linguistic knowledge, for a literal translation, code-switching, foreignizing; or to L2 knowledge, paraphrasing, use of semantically related terms or word coinage; or else, to non-verbal codes. This results in an implementation of communication strategies.

There are message avoidance or reduction strategies, achievement or compensatory strategies, stalling or time gaining strategies (Dörnyei, 1995). They imply problem-orientedness and consciousness, and appeal to the learners' strategic competence, which, according to Canale & Swain's framework (Canale & Swain, 1980; Canale, 1983), is one the four sub-competencies of communicative competence. The first three involve knowledge of the language code, of the sociocultural constraints and rules guiding its use, of the rules of discourse. The fourth implies the ability to use problem-solving devices to overcome impairment in communication in the other three. The study of communication strategies would thus benefit L2 communicative competence (Dörnyei & Thurrell, 1991).

Their implementation directly relates to the transfer of L1 skills, in that L2 users face more time processing problems with respect to L1 speakers (Dechert, 1984), when they have to plan and execute their utterances, given their lack of knowledge or of automatization of resources. The compensation is their additional problem-solving devices (Faerch & Kasper, 1986), in that they can draw for attempts from two sources, their L1 and their L2 (Cook, 1991). That does not mean that communication strategies are not to be implemented in the language teaching practice, on the contrary, as there are individual differences between the strategies in command of the student and their effective average use (Willems, 1987).

Therefore, learners should be instructed in the (language) classroom (Dörnyei & Scott, 1997), to be made aware of the existence of communication strategies, of their role in communication as problem-solving devices, of the communicative efficay of different communication strategies. Awareness can be raised deductively, through direct explanations or modelling, or inductively, through direct observation of interactants performing or the performance of communication tasks which involve problem-solving. The latter infers the identification of the problems experienced by the interactants and of the problem-solving mechanisms enacted, in a first phase; the assessment of the effectiveness of the solutions adopted, in a second phase (Tarone, 1984).

My study focuses on problem-solving devices, by proposing a didactic activity which at large attempts to contribute to inductively raise L2 learners' awareness of communication strategies. It cannot be collocated in the wider framework of a training scheme, which is without the domain of my design, but it intends to drawing on the relevance of implementing L2 learners' communication strategies as part of the teaching practice.

Bibliographical references

Antón, M. 1999. The discourse of a learner-centered classroom: Sociocultural perspectives on teacher-learner interaction in the second-language classroom. Modern Language Journal. 83: 303-318.

Apte, M.L. 1985. Humor and Laughter. An Anthropological Approach. Ithaca-London.

Attardo, S., and Raskin, V. 1991. Script theory revis(it)ed: Joke similarity and joke representation model. Humor 4,4-4: 293- 348.

Barfield, A., Dycus, D., Mateer, B., Melchior, E. 1998. FL Literacy: Meeting needs and realities in Japan. Literacy Across Cultures, September 1998 2/2. http://www2.aasa.ac.jp/~dcdycus/LAC98/SEP98/fll98rt.htm

Bennett, M.J. 1993. Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity. In Paige, M. (Ed.) 21-71. Education for the Intercultural Experience. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Berk, R.A. 2000. Does Humor in Course Tests Reduce Anxiety and Improve Performance?, College Teaching, 48(4): 151-158.

Brown, P., Levinson, S. 1987. Politeness. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bruner, J.S. 1969. Il pensiero. Strategie e categorie. Roma: Armando.

Cameron, J., Epling, W.F. 1989. Successful Problem Solving as a Function of Interaction Style for Non-native Students of English. Applied Linguistics. 10(4): 392-406.

Canale, M. 1983. From Communicative Competence to Language Pedagogy. In Richards, J. and Schmidt, R. (eds.) Language and Communication. London: Longman. 2-27.

Canale, M., Swain, M. 1980. Theoretical Bases of Communicational Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Testing. Applied Linguistics. 1: 1-47.

Cazden, C.B. 2001. Classroom Discourse: The Language of Teaching and Learning. Porsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Chiasson, P.E. 2002. Using Humor in the Second Language Classroom. The Internet TESL Journal, VIII (3), March 2002. http://iteslj.org/

Cook, V. 1991. Second language learning and teaching. London: Edward Arnold.

Danesi, M. 2003. Second Language Teaching. A View from the Right Side of the Brain. Springer.

Davies, C.E. 2003. How English-learners joke with native speakers : an interactional sociolinguistic perspective on humor as collaborative discourse across cultures. Journal of Pragmatics. 35: 1361-1385.

Dechert, H.W. 1984. Second language production: six hypotheses. In Dechert, H.W., Möle, D., Raupach, M. (Eds.), Second language productions, 211-230. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.

Donato, R. 1994. Collecting scaffolding in second language learning. In Lantolf, J.P. and Appel, G. (Eds.) Vygotskyan approaches to second language research. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 33-56.

Dörnyei, Z. 1995. On the teachability of communication strategies. TESOL Quarterly. 29: 55-85.

Dörnyei, Z., Scott, M.L. 1997. Communication Strategies in a Second Language: Definitions and Taxonomies. Language Learning, 47(1): 173-210.

Dörnyei, Z., Thurrell, S. 1991. Strategic competence and how to teach it. ELT Journal 45(1): 16-23.

Dynel-Buczkowska, M. 2006. Joking aside - sociopragmatics functions of conversational humor in interpersonal communication. Paper presented at the 3rd Lodz Symposium. New Developments in Linguistic Pragmatics, Lodz, Poland.

Faerch, C., Kasper, G. 1986. Strategic competence in foreign language teaching. In Kasper, G. (Ed.), Learning, teaching and communication in the foreign language classsroom. 179-193. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Fantini, A.E. 2000. A Central Concern: Developing Intercultural Competence. World Learning. Brattleboro, VT 1995. Revised 2000. www.sit.edu/publications: 25-42.

Fillmore, C.J. 1979. On fluency. In C.J. Fillmore, D. Kempler, & W. S-Y Wang, (Eds.) Individual Differences in Language Ability and Language Behavior, New York: Academic Press: 85-101.

Gardner, H. 1983. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligence. New York: Basic Books.

Genovesi, G., Valeri, M. 1973. Comico, creativitŕ, educazione. Rimini: Guaraldi.

Goffman, E. 1981. Forms of Talk. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kealey, D.J. 1990. Cross-Cultural Effectiveness: A Study of Canadian Technical Advisors Overseas. Hull, Quebec: Canadian International Developmental Agency.

Kerper Mora, J. 2003. Language Assessment. What It Measures and How.

http://coe.sdsu.edu/people/jmora/LangAssessmtMMdl .

Kinginger, C. 2000. Learning the Pragmatics of Solidarity in the Networked Foreign Language Classroom. In Hall, J.K., Stoops Verplaetse, L. (Eds.) Second and Foreign Language Learning Through Classroom Interaction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. 23-46.

Kohls, L.R. 1979. Survival Kit for Overseas Living. Chicago: Intercultural Network/SYSTRAN Publications.

Krashen, S. 1982. Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon.

Kristmanson, P. 2000. Affect: in the Second Language Classroom: How to create an emotional climate. Reflexions, 19(2): 1-5.

Mahovec, F. 1988. Humor. Springfield, IL: Thomas.

Manchón, R.M. 2000. Fostering the autonomous use of communication strategies in the foreign language classroom. Link & Letters, 7: 13-27.

Medgyes, P. 2002. Laughing Matters: Humour in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Norrick, N. 1993. Conversational Joking: Humor in everyday talk. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Norris, R.W. 1992. Errors, Humor, Depth, and Correction in the "Eisakubun" Class. Cross Currents. 19(2): 192-195.

Omaggio, A. 1986. Teaching language in context: Proficiency- oriented instruction. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Paksoy, H.B. (on line) Element of Humor in Central Asia: The Example of the Journal Molla Nasreddin in Azabaijan. Essays on Central Asia. www.ukans.edu/~ibetext/texts/paksoy-6/cae19.html (Jan. 27, 2001).

Parrott, T. 1994. Humour as a teaching strategy. Nurse Educator. 19(3): 36-38.

Pollak, J. P., Freda, P. 1997. Humor, Learning, and Socialization in Middle Level Classrooms. Clearing House. 70 (4): 176-78.

Powell, J., Andresen, L. 1985. Humour and teaching in higher education. Studies in Higher Education. 10(1) 79-90.

Provine, R. 2000. The Science of laughter. Psychology Today. November/December 2002, 33(6): 58-62.

Rappoport, L. 2002. Punchlines: The Case for Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Humor. Westport, Ct: Prager.

Schmidt-Hidding, W., Shütz, O., 1963. Humor und Witz. München: M.Hueber.

Seelye, H. 1993. Teaching culture: Strategies for inter- cultural communication. Third Edition. Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook Company.

Sever, A., Ungar, S. 1997. No laughing matter: Boundaries of gender-based humour in the classroom. Journal of Higher Education. 68(1): 87-105.

Shea, D.P. 1994. Perspective and production: Structuring conversational participation across cultural borders. Pragmatics. 4: 357-389.

Snow, C. 1992. Perspectives on second-language development: Implications for bilingual education. Educational Researcher, 21 (2): 16-19.

Solomon, R.C. 1997 (on line). Racist Humor: Notes Toward a Cross-Cultural Understanding.

www.arts-usyd.edu.au/Arts/departs/philos/ssla/papers/solomon.html (January 2001).

Stevick, E. 1982. Teaching and learning languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sullivan, P.N. 2000. Spoken Artistry: Performance in a Foreign Language Classroom. In Hall, J.K., Stoops Verplaetse, L. Second and Foreign Language Learning Through Classroom Interaction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. 73-89.

Tannen, D. 1989. Talking Voices: Repetition, Dialogue, and Imagery in Conversational Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tarone, E. 1984. Teaching strategic competence in the foreign-language classroom. In Savignon, S.J., Berns, M.S. (Eds.), Initiatives in communicative language teaching. 127-137. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Valeri, M., Genovesi, G. 1973. Comico, creativitŕ, educazione. Rimini: Guaraldi.

Varonis, E., Gass S. 1985. Non-native/non-native conversations: As model for negotiation. Applied Linguistics, 6: 71-90.

Veatch, T.C. 1998 (on line). Theory of Humor. The Internet Journal of Humor Research.

www.sprex.com/else/humor/paper/index.html (January, 2001)

Volpi, D. 1983. Didattica dell'umorismo. Brescia: La Scuola.

Vygotsky, L.S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Willems, G.M. 1987. Communication strategies and their significance in foreign language teaching. System, 15(3): 351-364.

Zadjman, A. 1995. Humorous face-threatening acts: Humor as a strategy. Journal of Pragmatics. 23: 325-339.

Ziegler, J. 1998. Use of humour in medical teaching. Medical Teacher. 20(4) 341-348.

Ziesing, M. (on line) Cultural literacy and language fluency.

http://www.utcc.ac.th/article_research/PDF/chapter2.pdf (January 2005)

Ziv, A. 1979. The teacher's sense of humour and the atmosphere in the classroom. School Psychology International. 1(2): 21-23. 5

Please check the Fun, Laughter and Learning course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Drama For The Language Classroo course at Pilgrims website.

|