The Effects of Attentive, Counselling-style Listening on the Participation of Japanese Students in Conversation: An Action Research Project

Clair Taylor, Japan

Clair Taylor has an MA in TESOL and is an instructor at Toyo Gakuen University, Japan. She is interested in NLP, CALL, and the design of learning environments. E-mail: clair.taylor@tyg.jp

Menu

Introduction

Listening and conversational flow

Setting the scene: the lounge and ‘lounge time’

The action research approach

The study and the intervention

Data collection and analysis

The findings

Conclusions and the way forward

References

Appendix A: The English Lounge at Toyo Gakuen University

Appendix B: Transcription Glossary

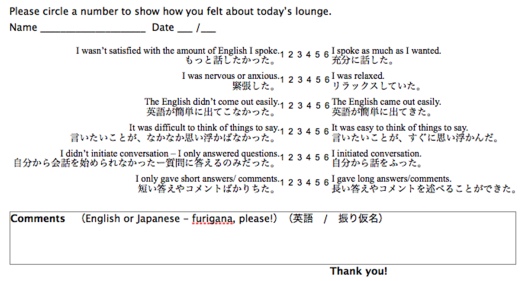

Appendix C: Feedback Form

Institutions offering EFL courses generally have an area in which students can converge to chat, such as a lounge or café. Teaching staff are often encouraged, or even required, to spend some time informally conversing in English with students in these locations. In Japan, conversation lounges are becoming increasingly common, since the Ministry of Education (MEXT) released their ‘Action Plan to Cultivate “Japanese with English Abilities”’(2003) which recommended that such spaces be promoted as a way to offer learners opportunities to use their developing English and experience ‘contact’ with English speakers. These lounges are not places for instruction but for learners to engage in real, ‘free-flowing conversation’ (Reedy, 2010:11). However, in practice, teachers may struggle to achieve this aim.

In my role as a teacher of English at Toyo Gakuen University I have been involved with setting up a conversation lounge. Some students make use of the facility, but teachers feel disappointed with the quality of the interaction. In our experience, conversation in the lounge tends not to flow easily, and feels ‘one-sided.’ Teachers ask students questions and follow-up questions, and the students typically respond with very short replies. Most students ask few questions and make few responses to contributions by other students. Some students appear tense or anxious, and sit with eyes cast down. There is a lack of energy; topics fall flat and the teacher works hard, constantly introducing new topics and attempting to introduce humour to improve the atmosphere.

Staff at other institutions seem to be encountering the same issues. One study found that participants at a public conversation salon in rural Japan rarely initiated talk, with native-speaker ‘Group Leaders’ leading the discussions (Birchley, 2006). At one university-based lounge, instructors reported frustration that students were quiet and took a passive role in the conversation, expecting the instructor to be the centre of attention, which left the teachers feeling like ‘entertainers’ and even ‘zoo animals’ (Rose & Elliot, 2010).

These difficulties may in part be explained by the students’ cultural and educational background. Japanese learners are noted for having problems speaking out in English in learning settings (Dwyer & Heller-Murphy, 1996; Brown, 2004). However, the problem is not confined to Japanese learners. Lindberg (2003) studied talk between conversation lounge volunteers and the immigrants who attend to practice their Swedish. The ‘conversation’ resembled classroom interaction:

the native speaker assuming the role of teacher, controlling and dominating the interaction thus, and doing most of the initiating and closing [leading to responses which are] elliptical and syntactically reduced, with few opportunities for sustained language use. (p.164)

This discourse has the Initiation Response Feedback (IRF) structure which characterizes classroom interaction (Sinclair & Coulthard, 1975). As part of the Initiating move, teachers select who is to answer their question by nominating a student or by cueing students to bid for a turn. Students then respond, and teachers provide feedback on this response. Conversations are also largely organized around three-part exchanges, but it is not always the same speaker who makes the initial move and the third part is not evaluative and is often realised non-verbally (Tsui, 1994). All participants can initiate, and there tends to be a sense of balance in the number of times the participants initiate, as there is in the length of their turns – there is symmetry. Van Lier and Matsuo define symmetry as ‘mutual orientation and dependency, a sharing of conversational rights and duties, and a convergence of perspectives’ (2000:269). In conversation lounges, many students fail to take on their share of the responsibility for continuing the conversation. The talk is typically asymmetrical.

The expectation that teachers can sustain ‘authentic’ conversation with students to a fixed schedule is problematic because there is inherent difficulty in trying to achieve non-institutional discourse in an institutional setting; ‘the institutionalized educational enterprise […] force[s] certain ways of speaking upon us which prevent true dialog or conversation from taking place, or at least discourage it’ (Van Lier, 1996:158). Drew and Heritage (1992) identify three characteristics of institutional interaction; inequality in the relationship, the need for one or both participants to be cautious, and goal-orientation. In language learning settings, there are inequalities in status between teachers (or volunteers) and learners. There are also inequalities in linguistic proficiency (a source of power). Teachers and students may both feel the need to be cautious, and the pedagogical goal will always be present. Research shows that when there is less equality in a relationship (in terms of roles, status, and other sources of power) there is less symmetry in the interaction (Van Lier & Matsuo, 2000; Carrier 1999). It would seem that asymmetry may be unavoidable in talk between teachers and students, even in a lounge setting. Yet, it still seems disappointing and unsatisfactory. Ultimately, IRF ‘strips the work of turn taking and utterance design away from the student’ (Van Lier, 1996:152). Students do not get to practice these important aspects of conversation, and thus are not prepared for the ‘real world’ outside. Van Lier and Matsuo (2000) argue that symmetry is the aim of any conversation, and failure to achieve it is traumatic. This may explain why lounge time feels so draining and tense. My dissatisfaction with the quality of the interaction in the lounge led me to embark on this piece of Action Research, exploring how to achieve greater symmetry in interaction in the lounge at my campus. I began by examining the role of the listener.

Listeners contribute to conversational flow. Takahashi (1989) found the ethnicity and sex of the listener affects the quantity, complexity, and fluency of speaker output. Psychological ease was also an important factor. The participants in this study felt the greatest sense of flow with one particular interlocutor who was rated highly for warmth, kindness, and humour (1989:273). Erickson (1996:290, 291) highlights the importance of the listener and listening style, stressing the ‘mutuality’ of interaction. He argues that fluency is ‘an ecological phenomenon, interactionally produced’ rather than a skill demonstrated by an individual.

For fluency and flow to take place, there needs to be rapport. Rapport can be defined as a state shared by people involving ‘mutual attentiveness, positivity, and co-ordination’ (Tickle-Degnen & Rosenthal, 2000). Rapport is achieved when people sense commonalities between them, and become ‘unified’ through their involvement with each other, as can be seen in their non-verbal co-ordination, such as mirroring postures.

It seems possible to transcend roles and inequalities in relationships with rapport. In Lindberg’s (2003) Swedish conversation lounge, increased symmetry was achieved at moments when the volunteers and learners found they had shared interests or backgrounds. There was a change of footing as the interactants established ‘co-membership.’ Nakahama’s (2005) study of a semi-structured interview between a bilingual Japanese and a Japanese learner of English showed how the institutional interview structure changed into a conversation as the two women ‘bonded.’ This suggests that it may be possible to achieve more conversational flow by focusing on attuning to the learners, by improving the quality of the listening attention that they receive. In order to develop a mode of listening that had potential to transform interaction in the lounge, I turned to the field of counselling, where powerful listening styles have been extensively explored.

Listening in counselling has been strongly influenced by the work of Carl Rogers, which has three main elements. Mearns and Thorne (1999:15) define the first of these as genuineness, or congruence; ‘be yourself without putting up a professional front or personal façade.’ The second is to accept rather than judge the speaker; offer unconditional positive regard. The last is empathic understanding, which they define as accurately sensing the client’s feelings and meanings. McLeod describes how Rogers listened, affirming attention through posture, nodding, checking understanding and restating, and acknowledging the unstated. He also provided reassurance, and at times maintained silence (2003:171).

Counsellors believe that quality listening has the power to draw out speech:

We do not listen to people because they are speaking to us. People speak to us, and speak to us in a particular way about particular things, because they are aware that we are open or not open to listening in a particular way. (Wilberg, 2004:57)

Wilberg argues that it is important that we do more than just give the appearance of listening. The listening goes much deeper than the behaviours that can be observed (nodding, leaning forwards) or recorded (repeating back the clients’ words, summarizing) – it involves changes to the counsellors’ mental, emotional and physical state, the counsellors’ whole being.

Practitioners working in the broad area of HLT have also explored ways to achieve quality listening. Underhill (1999:133) suggests that you can become a better facilitator in your classes by deepening the attention you give to students when they speak. He explains that this change is ‘entirely within’ and that we can listen ‘both to the words and the person behind the words.’ Stevick notes that when he acts as an interested conversation partner, volunteers speak more fluently, say more and the content is ‘richer’ than when he listens as a polite ‘elicitor and evaluator’ (1999:54). Doydon reports success in getting reticent Japanese learners to talk through creating a sense of intimacy, and adjusting non-verbal behaviour (1998:43). This attentive, genuinely interested listening style is clearly applicable to the situation in the lounge.

In this project I set out to explore how far a deliberate change in the quality of my listening could draw out more student output. This record of the project begins with a description of the setting. I then explain my research approach and describe the intervention. After discussing the findings of the project, I present my conclusions and consider the direction that the next cycle of Action Research could take.

The lounge at Toyo Gakuen University is a large, carpeted room equipped with tables and chairs, a television area with sofas, and a piano. Other musical instruments are available to use, in addition to board games, graded readers, newspapers and magazines (see photograph, appendix A). This four-year co-educational university offers undergraduate courses in Human Sciences, Business Administration and International Communication, and all students are entitled to use the lounge facilities. Each native-speaker teacher is scheduled 90 minutes of ‘lounge time’ per week and students of any year group and level are free to drop in and leave at any time. A typical lounge time might have 10 students attend, some arriving mid-way through and some leaving before the end of the session. This time is supposed to be spent in informal conversation rather than instruction.

I decided to take an Action Research approach, which could test one potential way to improve the problem situation in the lounge. I formulated this intervention-based question: “How far can adopting attentive modes of listening lead to more symmetry in conversations in the lounge?” I drew on accounts of how counsellors go about achieving quality listening with their clients, in addition to the descriptions of listening provided by HLT practitioners, to implement this change. Clearly, adopting the modes of listening which are usually associated with counselling is not a new innovation in EFL teaching, as counselling has influenced teaching for several decades. However, it was new for me to apply this approach systematically to this particular situation. In Action Research we ‘document’ our own learning as part of our personal professional development (McNiff, Lomax & Whitehead, 2003:178-181). By documenting the process I aim to develop my own practice, and validate my findings in order to provide a useable, sharable outcome.

Over six weeks I continued managing my lounge sessions the way I had the previous semester, listening in an ordinary way, and attempting conversation, recording the sessions. Over a period of six weeks I then experimented with listening to students in the way that counsellors listen to their clients, recording the sessions and collecting data. I then compared the data from both stages to examine how far the ‘attentive listening’ approach was successful in generating more student participation. To obtain informed consent, I displayed a bilingual statement outlining the purpose of the research and informing the students that conversations at one table would be recorded. Students could opt out by sitting at a different table.

For the listening intervention, I followed Friedman’s (2005) explicit direction in how to go about experiential listening. Before each session I spent approximately 10 minutes preparing myself, clearing my mind of any thoughts or worries, slowing my breathing, and adopting an open posture. I found it helpful to recall times in the past where I had been in deep rapport with another person, giving them my fullest attention. When I felt I had reached the physical state needed for deep, attentive listening I entered the lounge. In the lounge, I concentrated on maintaining this open state, and on giving each student that spoke my fullest attention, following Friedman’s practice of observing or ‘grokking’ the whole of the student so that I could be aware of their physical presence, postures and motions. Where students were silent, I concentrated on listening to the silence and observing the students, whilst maintaining an open posture directed at the whole group.

I recorded the sessions on a small digital recorder, placed on the table. The recordings were a major source of data, and the audio files were used to measure turn length. The next source was my journal, which included two forms of data. Immediately after each session, I wrote down my impressions (I), including observations and seating arrangements. Then, within two days of each lounge time, I used the technique of simulated recall (SR), playing back the recordings and making detailed notes on critical incidents, transcribing those sections of the session. The transcription conventions used are provided in appendix B. To find out from the learners’ standpoint how the intervention was experienced I constructed a feedback form using a 5-point Likert scale (appendix C). I also interviewed four participants, choosing students from different year groups and both genders to hear a variety of perspectives. These semi-structured interviews were recorded.

I then examined all the data, highlighting factors related to symmetry, rapport and flow. Turn lengths were tabulated and compared. The pre-intervention data provided a yardstick against which I could measure the success of the intervention. In the following section I present the findings and discuss issues which arose. First, I explore issues relating to the first stage of the project. I then examine my experience of preparing for and maintaining this attentive mode of listening, before moving on to discuss the results of the intervention, including some areas of concern.

Factors emerging from the first stage

The purpose of the first stage of the project was to provide data for comparison with the second ‘listening’ stage, yet a number of interesting findings emerged simply from recording and observing my lounge sessions without adapting my listening style. I noticed that the act of researching the lounge issue immediately reduced the severity of the problem, and changed my perspective. Before embarking on the project, I had tended to notice unsuccessful interactions and individuals who failed to participate. Objectively listening to the recordings, I observed that much of the interaction is in fact fairly successful, and that some students do backchannel and ask questions of each other, even when the atmosphere is quite tense. Observation increased my awareness that there was real diversity in the ways that students behave in the lounge - some chat and confer in Japanese (I 12/12b), others opt for silence (SR 12/10c). Some students do appear nervous (I 21/9), yet many others appear relaxed even if they say little, simply eating or watching (12/10a). Some students may have been responding positively to being part of the research project, just as others may have been inhibited by the recording device.

I also found that at times it was possible, without any technique or preparation, to slip into a state of high-quality listening. This occurred on two occasions, both times with female students who, at 23 years old, were more mature than other students. N lived in Canada for three years and has advanced level English. We talked naturally and it felt ‘intimate’ (SR 28/9), with high levels of disclosure. In a later session I spoke for 60 minutes with M. M has intermediate language skills and spoke at length, inducing a ‘trance-like’ (SR 10/12b) listening state in me as I became absorbed. The data from these two sessions support the idea that rapport and attentive listening correlate with long turns and high disclosure. They also indicate that the tendency towards symmetry will manifest itself when rapport is achieved. At one stage in the conversation with M there was a switch, initiated by the student, when she: 'turned the conversation around and became “the listener”, asking about my vacation.' (I 10/12b). I became the talker for several minutes and experienced being listened to: ‘It had become a real conversation’ (I 10/12b). Taking this into consideration, I decided that when listening in stage two, I would, if the students attempted to turn the conversation around, answer questions and become the talker, rather than fight this tendency towards symmetry. Wilberg argues that teachers should be prepared to talk about themselves, since authentic communication ‘would mean very little without biographical content’ (1987:25). Teacher disclosure may be part of the rapport-building process, contributing to conversational flow.

Achieving and maintaining quality listening

Examining the second stage of the project, it is necessary to evaluate whether it was in fact possible for me to alter my mental and physiological state, carry this clear state into the lounge and maintain it throughout the session. My journal shows that there was little difficulty in achieving this open, listening state: ‘I felt warm and open walking in’ (I 2/22). I was surprised to find that there was clear evidence of this change of state in the quality of my voice as I greeted the students. This was sensed at the time, and the change in timbre is clearly audible on the recordings. This change in voice quality was noticed by the students in one session:

[the greeting sounded] pure and clear and warm – it didn’t come out in my everyday voice. Everyone reacted. They jumped as if startled and exclaimed in Japanese, then translated, ‘Beautiful greeting!’ (I 9/11).

Achieving an appropriate state proved to be easier than maintaining it. In the recordings, the voice quality that marks out this clear, relaxed state is not maintained throughout the sessions. With anxious newcomers or difficult students the state is quickly diminished. I found myself slipping into habitual techniques, such as ‘pretending non-comprehension’ when students spoke Japanese (I 11/2a). Doing so, I failed to maintain the congruence required in Rogerian counseling. It was also difficult to keep my mind free of ‘internal chatter’, a pre-requisite specified by Friedman (2005:224) for being fully present and maintaining an open channel in counselling sessions. On one occasion, I entered the lounge to find two students watching a video, in addition to the four students who had arrived for lounge time. The room was cold and the students ‘were huddled in outdoor gear’. I describe the students as appearing ‘anxious’ and ‘uncomfortable’ which, combined with the temperature and the background noise, made it difficult to maintain an open, listening state: 'my eyes were darting about […] The blare of the TV was quite intrusive and I found it hard to concentrate.' (I. 16/11). This suggests that the environment also needs to be carefully prepared.

Rapport

Deeper listening seemed to improve rapport between myself and students, resulting in some students becoming much more relaxed. In early sessions (stage one) there was observable tension: ‘The students sat heads down, legs together, stiff. MS said, ‘Kinchou’ (I’m nervous).’ (I 21/9). Yet this same student produced in stage two a long narrative turn, which he initiated, and appeared very comfortable throughout. The journal entry records: ‘His eyes were shining and his face was pink and relaxed’ (I 16/11a). MS checked four on the feedback form for this session, where one indicated anxiety and six feeling relaxed, showing relatively low levels of anxiety.

The feedback forms indicate that anxiety was still an issue for some students. Third and fourth years selected five or six, as did first years who attend the lounge regularly, indicating that they felt relaxed. First years who were attending the lounge for the first time checked a range of scores from one to five, suggesting many felt considerable anxiety, even with the listening focus. Clearly, the listening approach is not an instant solution capable of generating a relaxing atmosphere with every combination of students. Yet, the journal does indicate that there was a high incidence of ‘moments of rapport’ in stage two. There are a number of references to making eye contact with students, and feeling closer to individuals as I listened deeply. The following extract from the journal describes one intense moment of rapport:

We make a real connection. I’d been listening hard, and I felt like the students were also listening deeply to me, so when I spoke I said something ‘real’ – not just something to get the conversation moving […] we had a moment of really shared understanding. There was eye contact, a sharp rise in energy, YM looked animated, with her eyes bright, and we were both nodding. (SR 30/11a)

Maintaining congruence seems to have played a role in this ‘convergence of perspective’, one of the aspects of symmetry of identified by Van Lier and Matsuo (2000).

Turn length

In order to evaluate how far deeper listening could lead to more sustained talk in the lounge, I measured the duration of long turns in each session. Long turns are multiple-unit turns, such as narratives or descriptions, in which the speaker holds the floor for some time, using prosodic, syntactic and other forms of projection, indicating there is ‘more-to-come’ (Selting, 2000). Within the speakers’ long turn there are contributions from the others present, mostly backchannels such as ‘yes’ or ‘mm hm’, but also questions and comments. The speaker uses these interjections along with non-verbal behaviour to monitor listener understanding and involvement (Ford, 2004). Here, I have measured the turns from the moment that the speaker takes the floor, and begins projection, until the last utterance that the speaker makes before the transition relevance place (TRP), the point where the next turn can begin. This TRP may be at the time the speaker makes this last utterance (in cases where the speaker nominates another speaker) or some moments later, perhaps after some laughter has died down, and a brief silence has ensued, and the floor becomes open for anyone to take.

Table 1 shows the longest single speaker turn for each session, and the number of students present at the time that the turn was made. The number in brackets shows that more people were present but not involved in that conversation. On 21/9, for example, eight students were seated in a circle with me, and one of them produced a turn of one minute and 57 seconds. At that time, there was a separate conversation happening on an adjacent table involving an American exchange student, a visitor and a fourth year, whilst on the other side of the room two girls chatted over a magazine. I have recorded here only single speaker turns. There were several examples of collaborative turns, where two or more students produced a narrative together, supporting each other in the telling. However these turns were less discrete, and the turn endings tended to be ambiguous.

| Stage One |

Stage Two |

| Date |

Length |

Number of attendees |

Longest turn |

Date |

Length |

Number of attendees |

Longest turn |

| 21/9 |

90min. |

8 (+3) (+2) |

1:57 |

2/11a |

45min. |

2 |

6:51 |

| 28/9 |

90min. |

1 |

1:37 |

2/11b |

45min. |

7 |

1:58 |

| 5/10 |

90min. |

2 |

34s |

9/11a |

45min. |

16 (+3) |

No data |

| 12/10a |

45min. |

3 (+4)(+6) |

No data |

9/11b |

25min |

4 |

4:16.5 |

| 12/10b |

60min. |

1 |

4:51 |

9/11c |

45min. |

6 |

1.20 |

| 12/10c |

45min. |

2 |

42s |

16/11a |

45min. |

2 (+3) |

14:30 |

| 19/10a |

45min. |

2 |

23s |

16/11b |

45min. |

4 |

4:00 |

| 19/10b |

45min. |

2 |

1:13 |

30/11a |

45min |

2 |

20:29 |

|

|

|

|

30/11b |

45min. |

5 |

1:25 |

|

|

|

|

7/12a |

45min. |

3 |

6:15 |

|

|

|

|

7/12b |

45min. |

4 |

51s |

|

|

|

|

14/12 |

45min. |

4 (+2) (+6) |

1.26 |

Table 1

Acknowledging that this type of study does not control for the many variables that may have affected turn-length (speaker proficiency level, number of people present, competition for turns, personality, etc.), the figures do suggest that deeper listening leads to more sustained student turns. Two turns are particularly long in stage two; YM’s 20:19 description of a seminar (R 30/11a) and AK’s 14:30 narrative about a childhood accident (R 16/11a). M’s 4:51 description of a mistake at work, the longest turn in stage one, is made in a one-to-one setting, yet in stage two the speakers making long turns are managing to hold the floor with several participants.

Students report that they valued these opportunities to tell their stories. In the feedback interviews, students were asked to identify a time when they had spoken fluently in the lounge. S recalled a session where I had been using the listening focus and he had recounted his love story. He felt that occasion was ‘special’ because ‘it was about me’ rather than ‘[social] issues’, suggesting that students feel comfortable talking on this personal level.

Flow

Conversational flow is largely a matter of subjective impression, but is also revealed by the way topics shift. Van Lier and Matsuo describe how, in conversations where symmetry is achieved, topic shifts are very subtle: They ‘just flowed from one into the other and were collaboratively established’ (2000:273). In a conversation with less flow, there may be a silence at the end of a turn, followed by someone bringing a new, unrelated topic to the table. This is an example from stage one, where T has been telling a story about finding his lost wallet:

T: yeah.

Clair: yeah, it’s nice, huh {This is a TRP following T’s long turn}

(5) {a cicada chirps as everyone in the room falls into silence}

Clair: who:::a! I wonder if that cicada is going to be on the recording!

I had to break the uncomfortable silence. (SR 21/9)

There are numerous references in my journal to the lack of momentum in the talk in the first stage. One entry notes: ‘I felt a sense of having to keep the ball rolling and wanted to get as much mileage as possible from each piece of stimulus’(SR 21/9). The comments point to the conversation having ‘little energy’ (I 12/10/), and a lot of silences which are ‘awkward’ and ‘distancing’ (SR12/10). Since the students did not attempt to fill the silences, I as teacher felt the pressure to do so, which made the sessions draining. The word ‘relief’ appears frequently in the journal.

In stage two, by contrast, there were few references to lack of flow. Some sessions were invigorating rather than draining; after the first session using the listening focus I wrote: ‘I felt sorry the time was up and stayed late to chat’ (I 2/11a). The afternoon session ‘ran over by 20 minutes’ (I 2/11b). Where I was able to maintain the listening focus, topics shifted smoothly. On 11/30b the recording shows that the topic moved from pet quarantine to hair salons to mercury in fish without a break. When silences occurred in the second stage, the listening focus allowed me to experience them as ‘pulling’ some output from the students: ‘I felt comfortable, they looked comfortable - the silences felt close rather than painful’ (SR 2/11b). These silences were broken by students:

(4)

{Everyone laughs}

H: mm

(2)

{Soft laughter}

(1)

{Loud laughter}

(1)

YK: I’m sleepy!

By focusing on listening I seem to have moved out of the ‘teacher’ role, and instead of feeling responsible for the silences I relax, leaving some space for the students to take responsibility for moving the conversation on.

Symmetry

One theme that occurred frequently in the data was that of ‘hostess’ duties. In stage one, the journal shows that I was taking full responsibility for making students feel welcome. When involved in conversation I was conscious of students in other areas of the room, ‘listening to their conversation to see if they were speaking English’ and making eye contact ‘to indicate they could engage with me and come over if they wished’ (I12/10). Like a hostess, I wondered how to ‘get the students to mingle’ (I 21/9). In every case of students meeting for the first time, I introduced the students. This extract from the journal details a typical response to a newcomer in the lounge:

AK does not stop his monologue to greet a student (NK) who arrives, or even signal a greeting non-verbally.

Clair: hello, come and join us {whisper, smiling voice}

[…]

The two students in the lounge do not know NK but make no attempts to introduce themselves or each other:

1 Clair: so I’ve never seen you in the lounge before? {to NK}

2 NK: fi fi first time. {eating}

3 Clair: really? ah. welcome. (1) do you know everybody?

4 NK: {shakes head}

5 Clair: we should introduce ourselves. this is YM, she is a (1) kokusai $international$ communication?

6 YM: yeah

7 Clair: kokusai communication student so the same as you, yeah.

8 NK: yes

9 Clair: NK is a first year, so K10.

10 NK: K9

11 Clair: K9. (SR 19/10a)

The students do not take responsibility for welcoming the newcomer, nor do they introduce themselves. At lines 4, 6 and 8 we might expect students to give their own names, yet they do not. Nor do they use any appropriate greeting language, such as ‘nice to meet you’.

In stage two, however, there is evidence of a shift in these responsibilities, with students taking on this role. Students ask each other their names and introduce themselves:

M: could you tell me your name?

MK: ah. MK. (SR 2/11b)

By moving into a listening role, I appear to have created a vacuum which pulls students into this host/hostess role. In the following extract from SR 30/11a, AK introduces me to another student, in a reversal of the roles we had taken in the stage one session:

{A student walks nearby. She had entered the lounge with AK.}

Clair: <I don’t know her name {nodding in the direction of the student}>

AK: she’s name is YS

Clair: YS. {to YS} hello YS

AK: {to YS} you can come our lounge time in this lounge or in Tuesday or {laughs} Tues- or Thursday

[...]

Clair: nice [to meet you]

YS: [nice to meet you]

{Clair and YS shake hands}

AK: she’s Clair

YS: Clair

Clair: nice to meet you. hi YS.

AK’s use of the term ‘our lounge time’ (underlined) implies that he has a sense of ownership of the lounge, another indicator of responsibility.

In addition to welcoming newcomers, the students also take more responsibility for initiating conversation, and feel the pressure of maintaining the conversation. There are several references in the journal to the conversation being run by students: ‘M is carrying the conversation’ (SR10/12), ‘H is driving the conversation’ (SR 2/11) and ‘YK is taking an active lead’ (SR 16/11b). In one incident, the dynamic is so controlled by one student that I have to bid for a turn:

H: and that’s it.

Clair: ok. I have a question {raises hand}

H: ok yep

Clair: if all these people… (R 2/11)

By focusing on listening I have moved away from the power position that is part of the teacher role. I did not have a greater right to speak, or a greater responsibility to speak, than any of the students. This, in fact, was the only aspect of my altered approach to lounge time that was detected by any of the students. When interviewed, YM felt there was little difference between the stage one and stage two sessions, but observed that in the second stage: ‘Sometimes we could ask student to student.’

There are strong indications that the listening approach was successful in bringing about a greater degree of symmetry in the conversation, reducing inequalities between teacher and students, and moving the teacher away from the central role. However, even as listener, I was at times inadvertently ‘leading’ the conversation, since students were interpreting my eye gaze as a form of speaker nomination. During a lull in conversation, if I looked at a student, the rest of the students would follow the direction of my eyes and look at the same student. With all eyes upon them, this student would feel under pressure to speak. Here, H, seated opposite me, is in my line of vision:

H: (8) what? (1) why so quiet?

{everyone laughs}

(2) talk! talk, talk!

I am aware that where I look is being taken as a sign of turn allocation. (SR2/11b)

Whilst this was not intentional, it meant that students within my sight spoke more than those hidden from view, and suggests that the power disparity was not entirely subverted, rather that it operated at a more subtle level. Conversationally, students did take on more of the work, yet this load fell to some students more than others. These conversational rights and responsibilities were not shared equally amongst the students.

The problem of unfair distribution of talk was raised by three of the four students interviewed. The younger students felt their seniors talked too much. Certainly, the longest turns in most sessions (in both stages) were taken by one of the oldest students in the group, and these seniors took more responsibility for keeping the conversation flowing. G’s comments show she was intimidated by older students because of their seniority and higher English level: ‘Second, third, fourth graders there were, so maybe I felt a little stress.’ S expressed concern that younger students cannot translate into English the keigo (polite forms) that they need to speak to higher grade students. The interviewees also revealed that some fourth year students had told lower grade students not to use honorifics when addressing them in the lounge, because they felt it was inappropriate for the English space. This confirms that seniority issues are significant.

The student interviews raised the issue that the listening approach may exacerbate the seniority problem, as ‘junior’ students feel unwilling to speak when there are senior students present, whereas seniors, when listened to attentively, take very long turns. YK felt that seniors should ‘show restraint’ and that, when listening deeply, the ‘teacher concentrates on one student only’ causing other students to feel left out. This suggests that the approach may need to be adapted to ensure that the junior students participate more. It should be noted, however, that the confident, fluent senior students provided role models for the younger students. YM reported that she wished to ‘become like them’ and S explained that these students were a significant influence on his development:

[to be like] T or H is my future goal. Thanks to meet [ing] them [I] was motivated to study English and my character changed a little. I used to be kind of shy and I didn’t talk anything but in lounge I can speak more, thanks to them.

Murphey and Arao (2001) have shown the value of ‘near peer role models’ to language learners, and it seems desirable that junior students have opportunities to see their seniors conversing well, as they did in the second stage of this project. The next cycle of research should aim to modify the listening approach in a way that still provides the senior students with the space to initiate and to take extended turns, whilst encouraging the junior students to speak.

This Action Research project set out to tackle the problem of awkward, asymmetrical interaction in the lounge at Toyo Gakuen University, where students were felt to be failing to initiate, to take long turns or to contribute much to the conversation. The primary aim was to establish how far adopting an attentive mode of listening, based on the way that counsellors listen to their clients, could alleviate the problem. Overall, the results showed that the listening focus did improve the situation. The listening focus appears to have led to increased student turn-length, rapport and conversational flow. These results are consistent with Doydon’s (1998) findings in classroom situations with Japanese learners and reflect the experiences of HLT practitioners (Stevick, 1999; Underhill, 1999), who report that improving the listening attention that they pay to learners can positively affect the quality and quantity of their spoken output.

Concentrating on listening led to greater conversational symmetry. The students took a greater share of the conversational rights and responsibilities, reducing the imbalance that had characterised much of the interaction in the lounge. The key factor was the problematic nature of the teachers’ role in the lounge. The listening approach involves listening with full attention, which releases the teacher from thinking about the social responsibilities of the lounge, such as welcoming students, and generating conversation. Consequently, the students began to take on these duties, introducing themselves and friends, breaking silences, and telling stories. This is consistent with Lindberg’s (2003) findings that learners will participate more actively in conversation lounges and take a greater share in the construction of the interaction when there is a move away from the ‘social identities’ that are associated with the roles of teacher and language learner.

Although attentive listening was at times possible, I was not able to maintain a high quality, congruent, listening state throughout each session. However, Mearns and Thorne point out that even for counsellors, learning to listen in this way is an ongoing process, ‘a lifetime’s work’ (1999:16), and not a skill that can be instantly mastered. Underhill (1999) also stresses that developing and deepening the way we listen is a gradual process. The findings of this project suggest that it would be worth pursuing this approach.

One aspect that I had underestimated in designing the intervention was the anxiety caused by hierarchical relationships between students. These institutional relationships made it difficult for the younger students to participate as fully as they wished in the sessions. To address this issue, the next research cycle could explore seating arrangements. Moving seats several times in a session would prevent my eye gaze from settling on the same student(s). Since the recipient of my eye gaze tends to feel the pressure to fill the silence and keep the conversation moving, it may shift this sense of responsibility onto different students, creating more overall symmetry.

As Action Research, this study was interested in the specific situation of the lounge at my workplace and, as such, the findings may not be generalisable to other settings. Yet the findings of the study may have implications for teachers working in similar conversation lounge environments, who could experiment with attentive listening styles to increase symmetry and conversational flow.

Birchley, S. L. (2006). Talking or teaching? An English conversation salon: Gunma prefecture, Japan. Bulletin of Gunma Prefectural Women’s University No. 2:117-130.

Brown, R. A. (2004). Learning consequences of fear of negative evaluation and modesty for Japanese EFL students. The Language Teacher, 28/1:15-17.

Carrier, K. (1999). The social environment of second language listening: Does status play a role in comprehension? The Modern Language Journal, 83:65-79.

Doydon, P. (2000). Shyness in the Japanese EFL class. The Language Teacher, 24/1:11-17.

Drew, P. & Heritage, J. (1992). Talk at work: Interaction in institutional settings. Cambridge: CUP.

Dwyer, E. & Heller-Murphey, A. (1996). Japanese Learners in Speaking Classes. Edinburgh Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 7:46-55.

Erickson, F. (1996). Ethnographic microanalysis. In McKay, S. L. & Hornberger, N. H. (eds.) Sociolinguistics and language teaching. Cambridge: CUP.

Friedman, N. (2005). Experiential Listening. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 46/2:217-238.

Ford, C. E. (2004). Contingency and units in interaction. Discourse Studies, 6/1: 27-52.

Lindberg, I. (2003). Second Language Awareness: What for and for whom? Language Awareness 12/3&4:57-171.

McNiff, J., Lomax, P. & Whitehead, J. (2003). You and Your Action Research Project (2nd Edn.) London & New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

MEXT (2003). Action Plan to Cultivate “Japanese with English Abilities.” Retrieved from: http://www.mext.go.jp/english/topics/03072801.htm

Mearns, D. & Thorne, B. (1999). Person-centred counseling in action (2nd edn.). London: Sage.

Murphey, T. & Arao, H. (2001). Reported belief changes through near peer role modeling. TESL –EJ 53:1-15.

Nakahama, Y. (2005). Emergence of conversation in a semi-structured L2 English interview. Studies in Language and Culture 27/1:133-147.

Reedy, D. (2010). Aoyama Gakuin Chat Room. TYOchap’zine. 1:11.

Rose, H., & Elliott, R. (2010). An investigation of student use of a self-access English-only speaking area. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1/1:32-46.

Selting, M. (2000). The construction of units in conversational talk. Language in Society, 29:477-517.

Sinclair, J. & Coulthard, M. (1975). Towards an analysis of discourse. Oxford: OUP.

Stevick, E. W. (1999). In Arnold, J. (ed.) Affect in learning and memory: From alchemy to chemistry. Affect in language learning. Cambridge: CUP.

Takahashi, T. (1989). The influence of the listener on L2 speech. In Gass, S., Madden, C., Preston, D. & Selinker, L. (eds.) Variation in Second Language Acquisition: Discourse and Pragmatics. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Tickle-Degnen, L. & Rosenthal, R. (1990) The nature of rapport and its nonverbal correlates. Psychological Inquiry 1/4:285-293.

Tsui, A. (1994). English conversation. Oxford: OUP.

Underhill, A. (1999). Facilitation in language teaching. In Arnold, J. (ed.) Affect in Language Learning. Cambridge: CUP.

Van Lier, L. (1996). Interaction in the language curriculum. London & New York: Longman.

Van Lier, L. & N. Matsuo (2000). Varieties of conversational experience: Looking for learning opportunities. Applied Language Learning, 11/2:265-287.

Wilberg, P. (1987). One to one: A teachers’ handbook. Hove: LTP.

Wilberg, P. (2004). The therapist as listener. Eastbourne: New Gnosis Publications

False start wo-word

Overlapping text word [word]

[word] word

Micropause (.)

Longer pause (.5) (pause time in tenths of a second)

Whispered < >

Lengthened segment wo:rd (more colons = more stretching)

Additional information {comment} (includes non-verbal information; coughs, laughs, etc.)

English translation $English$

Please check the Skilled Helping & Feedback course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Coaching Skills for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|