Modelling the English Learning Process of Foreign Students in Singapore: Thematic Analyses of Student Focus Groups

Sng Bee Bee, Anil Pathak and Stefan Karl Serwe, Singapore

Dr Sng Bee Bee is an independent researcher and adjunct tutor. She is interested in English for Specific Purposes and Academic Writing Skills. She has written on educational change in Singapore and how international students find learning English in Singapore. E-mail: bbsng777@gmail.com

Dr Anil Pathak is an Assistant Professor at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. His research areas are communication, discourse, and new texts. He has published in several journals including Web-based Communities, Business Communication Quarterly, ESPM, PaCall, PASAA, and Internet TESL. E-mail: ASalpathak@ntu.edu.sg

Stefan Karl Serwe is a lecturer at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. He teaches communication skills and German language. He is interested in conversation analysis and language contact phenomena. E-mail: skserwe@ntu.edu.sg

Menu

Introduction

Multilingualism in Singapore and the role of English

Earlier research

Method

Purpose, focus, and the research question

The research method

Data collection and data analysis

Results: Thematic analysis of data

Use of different languages which are foreign to the international students

Code-switching and code-mixing

Adoption of adapted version of Singlish

Different varieties of spoken English

Coping strategies: Accommodation and assimilation

Conclusion and suggestions for further research

References

For the last ten years or so Singapore has been actively trying to establish itself as a premier destination in Asia for education and research. More and more Asian students prefer Singapore as their study destination over traditional choices in the region such as Australia and New Zealand. Besides cultural similarities, economic considerations and factors such as political stability and security, Singapore is being chosen due to the possibility of pursuing a university degree in English (Han 2007). An expert advisory panel to the Singaporean government (Ministry of Trade and Industry, Singapore 2007) identified the use of English in Singapore as a major asset in the republic's plans to triple its currently 50,000 strong international student community by 2015. Indeed, Singapore is one of the few countries in Asia which has adopted English as the main medium of instruction in its schools and universities.

However, as analyses by Tan (2003) and Kuo and Jernudd (2003) point out, there is more going on under the cloak of the macro-sociolinguistic perspectives often adopted in studies of Singapore's multilingualism, in particular with regard to the status of English. The linguistic reality is a far cry from often-employed simplistic descriptions, such as “[e]ducated Singaporeans speak two kinds of English, Standard English and Singlish. Standard English is what we speak in formal contexts and with non-locals. Singlish is what we speak to each other when we want to show bonding and intimacy.” (Lee 2005:71).

Our aim in this paper is to model the process of language learning when the learners try to pick up a language in complex real-life-situations in Singapore. In an attempt to build an awareness path for the language teaching practitioner with the use of this model, we seek to address the language situation from the perspective of foreign learners of English studying at the tertiary level. By describing the learners’ assessments of their learning environment, as well as the strategies used by them to cope with the linguistic challenges, our study attempts to describe the English language learning environment in a country at the periphery of the English speech community.

Whether due to social necessity, the creation of a national identity (Kuo and Jernudd 2003), pure political pragmatism (Purushotam 2000; Tan 2003) or an interplay between these local factors and the pressures of the global market economy (Stroud 2007), English was awarded its place as national language and language of administration alongside Malay, Mandarin Chinese and Tamil at the dawn of Singapore in 1965. Although English is only “the native tongue of less than 20% of the population” (Pakir 1999:107), it is a code of high social prestige being associated with upward mobility and power (Tan 2003). On the other hand, it has a unifying function. Standard Singapore English and its colloquial variety, Singlish, are used as the linguae francae in interethnic interactions (Kuo and Jernudd 2003).

While these characteristics remain largely valid today, a trend towards domain transcendence and competition has become ever more visible. English has been extending its influence beyond its traditional domains of bureaucracy, work place and academia into the homes of many Singaporeans. The General Household Survey 2005 (Department of Statistics 2005) illustrates that in areas where once the ethnic languages dominated, English is creeping in. Interestingly, however, while English appears to be eroding the functions of the mother tongue for many Malay and Indian Singaporeans, the use of Mandarin among Chinese Singaporeans has increased significantly across all domains, even at the expense of English. The report (Department of Statistics 2005:17) states that “there appears to be a greater tendency to switch from Chinese dialects to Mandarin than to English at home among the Chinese resident population at all educational levels. Between 2000 and 2005, the proportion speaking Mandarin increased more rapidly than English even among university graduates.”

Thus patterns of language use in Singapore are complex, with English and Mandarin Chinese being used as the ‘prestigious’ codes and linguae francae, while other Chinese dialects, Malay, Tamil and Hindi, as well as Singlish being restricted to informal and private domains. Singlish is specifically targeted and being ‘deregistered’ in the formal circles of linguistic prestige.

There are very few studies that have looked at learning English as an L2 in Singapore. Mackey and Silver (2005) studied primary school children from immigrant families. In the university context, Lee et al. (2003)’s collection of study does stand out. A primary concern of these studies is with the experiences of EFL practitioners teaching English to Chinese nationals. Although some studies primarily deal with the evaluation of instructional tools used in the EFL classroom, a few of them offer an insight into the foreign students’ perceptions of Singapore as an EL learning environment and how these students deal with the multilingual environment.

Young (2003) studied Chinese students’ attitudes towards varieties of Singapore English. The results indicate that subjects’ understanding and appreciation of Singapore English improved over a period of six months. The study shows how the students managed to adapt to the local variety after initial feelings of rejection. As the author rightly concludes, students from countries other than the People’s Republic of China might have a different set of attitudes. Goh and Tan’s (2003) analysis of reflective emails by Singaporean ESL and Chinese graduate EFL learners reveals more specific information on their learning experience. The study focuses on comprehension and production of spoken Singapore English as the main problems for the Chinese students. Interestingly, two of the four problem sources are the lack of need to use English with peers and the many different accents of English used in Singapore. With regard to Singaporean ESL students the study identifies the widespread use of the colloquial variety of English and language alternation as causes for their low proficiency in English.

Much of the EFL research focuses on traditional EFL contexts where learners study English in one of the five English speaking countries: US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. It has been (sometimes incorrectly) assumed that these insights are directly applicable to Singapore's situation due to its English-centric policies. This assumption seems to have led to a divorce between the linguistic reality and the EFL position adopted by institutions. Taking this as the starting point, our modest study tries to focus on the linguistic reality by taking into account learner reflections on their learning and coping strategies.

The study seeks to address the following question:

What learning and coping strategies are used by university students when they migrate to an English-speaking environment such as Singapore?

The answers to this question should help us attain the following research purpose:

To model the English learning process and experiences of international students who have migrated to an English speaking environment (such as Singapore) in order to create data that can be used by ELT curriculum designers.

Focus group discussions were carried out with international students enrolled in a technological university in Singapore. We consider focus group discussion as another kind of interview research method. Following Morgan (1997) we designed the discussions such that the focus is provided by the researcher.

One of the strengths of focus group research is that it generates a vast amount of data on views of a particular topic. In addition, it is able to produce quantity and breadth of feedback on an issue (Krueger 1994). It is also able to produce a large amount of data on a topic of interest (Morgan 1997). Furthermore, it allows the researcher to observe the group’s interaction on the research topic. The advantage that focus groups research has over interviews is that it provides the opportunity to observe interaction (Morgan 1997). In addition, it allows the researcher some amount of control in the discussion (and, by implication, on data collection) since s/he is the one to set the focus and agenda. This makes focus group research a suitable method for the objectives, conduct and analysis of this study.

Participants were first year students of the Engineering degree program. Convenience sampling was used and the researchers informed their students of the aims, research questions and dissemination of the research results and asked if they would like to participate in the research. Students were given some time to consider and then met to conduct the discussions. The researchers encouraged the students to respond freely and comment on the issues. Each focus group contained 10-12 participants and the discussion was video-recorded. Initially the students were rather hesitant in their responses but as they became involved in the discussions, they became more animated. Since this was an issue close to their hearts, they were very keen to express opinions of their experiences and difficulties in learning English in Singapore.

The video-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. In the first stage of data analysis, data reduction was carried out. This involves summarizing the data, coding, memoing and finding themes, clusters as well as patterns (Punch 1998). At the next stage common themes that occurred and recurred in the transcripts were identified. These themes were then classified in five broad categories:

- Use of different languages which are foreign to the international students

- Code-switching and code-mixing

- Adoption of Adapted Version of Singlish

- Different Varieties of English Spoken

- Coping Strategies: Accommodation and Assimilation

This thematic analysis is presented in the next section.

As identifies at the level of thematic analysis, the issues raised by the international students with regards to how they find learning and using English in Singapore have to do with the use of different languages; varieties of English; code-switching and code-mixing among Singaporean speakers. We present our data analysis below. The utterances have been labelled for the convenience of the reader. FG stands for Focus Group, S stands for Student. Thus, (for example) the label FG1S3 means the utterance is attributed to third student in the first Focus Group.

The data suggests that how foreign students perceive the use of different languages in their environment greatly depends on two variables: ethnicity and language proficiency. Thus, the experiences of students from China and an Indonesian student of Chinese origin differ significantly from each other and from those of a Cambodian student.

In Singapore, it is safe to assume that the overwhelming majority of Chinese Singaporeans is able to understand Mandarin. Therefore, Chinese nationals find themselves in familiar linguistic and socio-cultural territory when coming to Singapore. As a student (FG1S3) puts it, “Singapore is more like a Chinese-speaking country so I can get used to this country very easily.”

Nevertheless, while the possibility of using Mandarin for most communicative situations in Singapore facilitates their integration, most Chinese regard it as a hindrance to their learning process. This opinion is mirrored in several examples in the data. Opinions such as these challenge the ambition of the Singapore educators to make Singapore a significant education hub. The reason cited is the dominance of Mandarin inside and outside the classroom.

| FG2S9: |

I think for me -all of them are Chinese- So we didn’t use English very often When I come to lecture or tutorial- sometimes I just cannot understand what they say-I think it is very difficult for me. |

This particular student comments on the language use during the bridging course. If this student’s opinion (supported by other students) is anything to go by, it seems that at least outside the classroom the use of English is not necessarily required. The students blame this lack of practice (and exposure) for their present communication problems in English.

However, as the following statement by an Indonesian student suggests Singaporeans are able and willing to adjust their language use to English, the neutral and official code, in goal-oriented mixed group contexts, such as a meeting, to facilitate interaction.

| FG1S7: |

I think the best way uh I have experience … when we had meeting my first meeting uh -- my leader said to me “Can you speak Chinese?” and I said “cannot” I cannot speak Chinese so for the whole meeting he and other member used English or maybe sometimes Singlish, it’s okay. |

Contrary to their Chinese peers, Indonesian students seem to prefer the use of English with Malay Singaporeans, despite the similarities between Bahasa Indonesia and Bahasa Melayu. The communication problems are resolved by using English:

| FG2S3: |

We combine – sometimes we speak English sometimes we use Bahasa. The case is the Bahasa the Malayu one- the Malay one we can understand them but sometimes they cannot understand us … |

Nevertheless, for non-Mandarin speaking students, language use in Singapore poses a very different set of problems. For example the use of Mandarin by Chinese Singaporeans may not only lead to misunderstandings, but to feelings of exclusion in non-Mandarin speaking foreign students, like the following statement by a Cambodian student illustrates:

| FG2S2: |

but sometimes it’s a bit hard with them. Because I have a lot of friends- They tend to speak Chinese with each other. So sometimes I feel a bit left out. …So my close friends in Singapore are all from- Indians- Malays- not Chinese. |

As this student indicates in the last part of her utterance, this mismatch of codes has had significant social consequences in her case, because it directly influenced the composition of her circle of friends.

The data suggests the complexity of the linguistic situation in Singapore. The data demonstrates the lack of target language (English) exposure. It shows the struggle of students who indicate that, contrary to the popular opinion and belief, Singapore does not emerge as an immersion-type setting for learning English.

Auer (1998) suggests that instances of language alternation are either alternational, between whole stretches of talk, or insertional, on the constituent level. If the code changes have a contextualizing function, then we deal with codeswitching (CS), otherwise with codemixing (CM). Our data suggests that language alternation is not necessarily an impediment to communication for the foreign students. The data shows that CM is generally understood and accepted, whereas certain forms of CS pose problems for the overwhelmingly monolingual foreigners.

Instances of insertional CM are often cited by our informants and this is usually done with great amusement. Almost all of them were able to cite an example or recognized the authenticity of those given by their peers. Many also admitted using them actively in their own speech with locals and among other foreign students. This indicates that they have acquired them alongside English vocabulary items. The two examples below show a Hokkien adjective and a Malay adverb embedded in otherwise English utterances. Important to note is that subject FG1S8 recognizes that the users of his CM example are otherwise not proficient in Malay

| FG1S8: |

I hear “you are quite a /dao/”. /dao/ is of course not English and not Mandarin.

/dao/ I think is Hokkien or Cantonese. You are quite /dao/.

[/dao/ Hokkien ‘arrogant’] |

| FG1S8: |

I don’t think all the Singaporean can speak Mandarin, but they, sometimes they

often use one quite a popular words like agak-agak I don’t think they can speak Malay, but they use it agak-agak means, I think, it’s ‘ roughly’. |

This conventionalized pattern of code change, which is devoid of functional or direct contextual meaning, might be counted as what is colloquially referred to as Singlish. Interestingly, the students seem to approve of this type of language alternation.

On the other hand, alternational CS is reported to be used by local Singaporeans due to the phenotype of their interlocutor or the topic of conversation. The data shows that this phenomenon poses a dilemma for the foreign student. Even if English is his or her preferred communicative code in interactions with a local, the Singaporean’s ability to codeswitch inhibits the use of English and can thus act as an obstacle in the foreign student’s learning process.

One of the varieties of English spoken by locals in Singapore, known as Singlish, poses some problems for the international students’ use and learning of English. Since the vernacular is arguably more frequently used among Singaporeans in informal settings than Standard Singapore English, foreign students may not even see the need to apply the skills that they have acquired in the classroom setting.

Alsagoff (1995) cautions that the notion of Singlish as a ‘bad’ form of English comprises a sociolinguistic judgment as well as a statement about its grammar. In terms of grammar, Singlish does not follow all the rules of Standard English grammar. In terms of sociolinguistics, it implies that Singlish is a lower prestige variety. Students’ attitudes, however, vary. One of the students observed that different students respond to Singlish in different ways. There were students who were adverse to its accent. Other student indicated that, when communicating with Singaporean students, they accommodated to the locals’ variety of English.

| FG1S7: |

Depends on the students. |

| FG1S4: |

Some student don’t like the accent. Prefer the standard English, they don't like to speak Singlish. |

| FG1S3: |

For me, I’ll not try to speak Singlish, but I can understand it (nods his head). |

| FG1S4: |

If you communicate with the local students, most times you will follow them to speak their language. |

The foreign students seem to be well aware of the problems, but also the benefits of the local vernacular. One student commented that as a variety of English, there is ambiguity about whether it should be considered an acceptable standard of English. He gave the example of how a professor corrected them on the use of Singlish in a formal event in the University and advised them to use standard English. The professor who corrected them is a Singaporean.

One of the important issues that arise in this discussion of the use of Singlish in Singapore is how it affects students’ learning of English. One of the students admitted that his English suffered from the use of Singlish, adding jokingly that his Singlish had improved. The key issue that needs to be addressed is the comprehensibility of Singlish beyond Singapore. The student explained that when he used Singlish while talking to a friend in his home country, his friend commented that his grammar was incorrect and he thus doubted his ability to communicate with such poor grammar.

Many students confessed that their English did not improve much as they became accustomed to using Singlish. One of the students deemed the communication of intended message to be more important than the use of standard grammar. He felt that as long as the listener understood the intended message, it is adequate. He thought it pointless if one spoke in perfect grammar all the time.

While Singlish can be regarded as a dialect of English, there are also other varieties of English spoken by Singaporeans which are closer to internationally accepted standards of English. This is also the variety spoken by Singaporeans who studied abroad like in Britain for example.

| FG1S8: |

… I think they study abroad. Their English is quite good, everyone can understand. I think it’s best for us to be like that, if we speak Singlish, then when we go out of Singapore, other people cannot understand. |

Linguists explain that there are many ways of approaching the English of Singapore. The three prevalent ways are to view Singapore English as imperfectly learnt Standard English; deficient; or as a dialect of English best analysed in its own terms. Although such a view is valid among linguists, the students struggling to learn English would suffer more if such a view is propagated or even accepted in an educational setting.

Some of the international students in the focus groups consciously rejected Singlish and refused to speak it. They were also influenced by the different varieties of English used around them. Through this exposure, some have adopted a kind of American English accent only to find that others around them do not subscribe to this variety. As a result of their rejection of Singlish and their imitation of the American English in the media, their communication with other students suffers.

| FG1S8: |

.., uh.. I think they don’t have the atmosphere to speak, so when they speak American English, others don’t understand them, and they don’t want to speak Singlish, then they, their communication with others is quite bad.

|

Apart from these accents, foreign students are exposed to a great variety of international accents and standards of English on behalf of the teaching staff at the University. Asked about this students frequently commented on the variety of English used by some of the University’s Chinese faculty (Chinglish), which the students found less problematic to understand than the locals. This shows the complexity of communication in the multilingual community of the campus.

Accommodation and assimilation have been well-researched as factors that affect positively (and sometimes negatively) language learning of foreign learners. We accommodate others by adjusting our communicational behaviour to the requisite roles that participants are assigned in a given context. As one student puts it, it is more of a ‘following’ than learning standard grammar.

| FG1S4: |

If you communicate with the local students, most times you will follow them to speak their language. |

Giles and Coupland (1991) consider language as "socially diagnostic" since it gives a basis to many users to make informed guesses on the speaker’s status, education, class, or even intelligence. FG1S6 narrates an experience:

Student 6: …..And I have ever held an event, formal event, in which we invite the professors, and unfortunately, we used the Singlish, so some of the committees used Singlish, and the professors thought it was quite, not, meaning ‘acceptable’ (used fingers to gesture parenthesis) so he suggested that for the next time event, please use the standard English, instead of Singlish.

Accommodating to others' speech may prove either beneficial or damaging depending on the context of the situation. Immigrants whose command of ‘standard’ (or ‘local’) English is not "up to the mark" are bound to lose some of the educational and career prospects. Some students are well aware of this and work hard to learn the local variety of English.

A very common modification of speech is convergence, that is, the processes whereby two or more individuals alter or shift their speech to resemble that of those they are interacting with. By the same token, divergence refers to the ways in which speakers accentuate their verbal and non-verbal differences in order to distinguish themselves from others. This is reflected in a student’s (FG1S8) comment mentioned in section 3.3.

Proponents of segmented assimilation (Portes and Zhou 1993) or accommodation without assimilation (Gibson 1989) argue that these groups prosper by deliberately preserving their cultural values and promoting ethnic solidarity.

In this paper our intention was to focus on the coping strategies used by the foreign students studying in Singapore. Using the data obtained from focus groups we were aiming to model the process of informal (on-the-street) learning of these students. The issues raised by the international students’ with regards to how they find learning and using English in Singapore have to do with the use of different languages; varieties of English; code-switching and code-mixing among Singaporean speakers. With reference to our data, we focused on the linguistic challenges that EFL students face while learning English at a university in Singapore.

Singapore is one of the few countries in Asia where English is used as a medium of instruction in all levels of the education system. Students from all over Asia and the Middle East come to Singapore to study, from as young as secondary school level. This is why Singapore is likely to be a major education hub in the South East Asia. In this project we tried to study how foreign students who come to Singapore cope with their learning and use of English.

We began with the premise that the conventional EFL research presents rather simplistic solutions which may not be suitable to the unique multilingual situation in Singapore. Some of the peculiar aspects of this situation were described in our discussion of the focus group interactions. A number of student comments bring out the peculiar features of language use. It proves that outside the classroom the use of English is not necessarily required. However, the students admit that this lack of practice is the source of their present communication problems in English. Several instances in the data corroborate this lack of opportunities to communicate in English. However, at the same time, some students from China encounter communication problems within the Singaporean Chinese community, because of the frequent use of Chinese dialects, like Hokkien, Teochew or Haka. For non-Mandarin speaking students, such as Indonesians' and Cambodians the use of Mandarin by Chinese Singaporeans may not only lead to misunderstandings, but unconsciously or deliberately to feelings of exclusion in non-Mandarin speaking foreign students. In the discussion section we also focused on issues such as language alternation. Some instances in the data seem to indicate several aspects: instances of language alternation appear frequently in the speech of groups dominated by Singaporeans, but they may not always prove to be problematic to the foreign students.

It is quite clear that these peculiar aspects of the multilingual situation in Singapore lead towards a model that represents a much more complex learning activity. It is quite clear from the focus group interactions that the learning experience students depict is quite different from the traditional EFL contexts.

In any model of language learning activity we handle the challenge of linking cultural beliefs with attitudes, motivation, situational anxiety, and prior achievement to proficiency in a second language. Such challenges become more precarious in unique multilingual situations. The research data shows the large range of coping strategies that adult learners use to survive and succeed when they are immersed in a new language environment. For a curriculum designer and a language teaching practitioner, it would be useful to investigate and to incorporate some of these strategies in a formal curriculum. This research is a small attempt to discover some of these strategies and to attempt to model the process of language learning in an immersion-type setting.

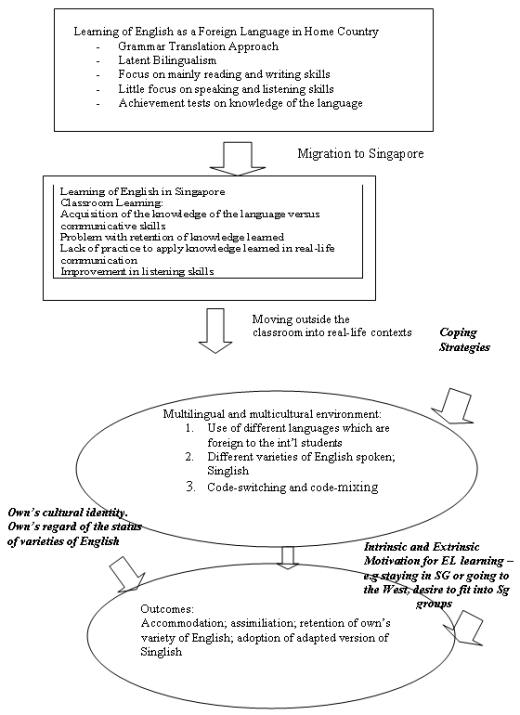

Combining the theoretical perspectives we outlined in the Background section and the perspectives we obtained from the focus group interactions, we were able to build a model of the learning process of the international students. The model is presented in the figure below.

We are aware that the framework and the model emerging from our research does need further elaboration. At this stage the model provides a rough and ready guide for any EFL practitioner in South East Asia for designing courses, materials, and teaching practices. What the model essentially points out is the nature of the intricacies in the EFL contexts that are deeply rooted in the multilingual situation in Singapore. As we have pointed out earlier, dichotomies such as Singlish and Standard English appear rather simplistic in this context and provide little help or direction to the practitioner who wishes to develop strategies and practices specifically for these EFL contexts.

Further research is required in several areas in this direction. First, it is necessary to validate the model framework we have created. Large data from various universities and other teaching institutions would be required for this purpose. From our experience, the focus groups seem to be the best resource for obtaining such data. Interviews of and focus group sessions with teachers and educators can further help validate this model.

Secondly, it would be important to draw more direct linkages from the model framework to the classroom implications. It would be good to understand how various features of the model directly or indirectly feed into various classroom implications. This is indeed a creative and multi-dimensional exercise that has tremendous practical value. This area has tremendous scope for applied research. We look forward to any such manifestations of the direction we have demonstrated in this paper.

Alsagoff, Lubna, (1995) Colloquial Singapore English: The Relative Clause Construction. The English Language in Singapore – Implications for Teaching, ed. by Teng, Su Ching and Ho Mian Lian, 77-87. Singapore: Singapore Association for Applied Linguistics.

Auer, Peter, (1998) The pragmatics of code-switching: A sequential approach. One speaker, two languages: Cross-disciplinary perspectives on code-switching, ed. by Lesley Milroy; and Pieter Muysken, 115 - 135. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Department of Statistics, (2005) General Household Survey 2005: Statistical release 1. Socio-demographic and economic characteristics. www.singstat.gov.sg (13/8/2008)

Gibson, Margaret, (1989) Accommodation without Assimilation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Giles, H. and N Coupland, (1991) Language: Contexts and Consequences. Keynes: Open University Press.

Goh, Happy; and Tan Kim Luan, (2003) Reflections of ESL and EFL students through email: An exploratory study. Teaching English to students from China, ed. by Lee Gek Ling; Laina Ho, J.E. Lisa Meyer, Chitra Varaprasad and Carissa Young, 54-72. Singapore: Singapore University Press.

Han, Bernice, (2007) World's leading schools set up campuses in Singapore. The Straits Times, Monday Dec 10 2007. www.asiaone.com (12/8/2008)

Krueger, R.A. (1994), Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. California: Sage Publications.

Kuo, Eddie; and Björn Jernudd, (2003) Balancing Macro- and Micro-Sociolinguistics Perspectives in Language Management: The Case of Singapore. Babel or Behemoth: Language Trends in Asia, ed. by Lindsay, Jennifer; and Tan Ying Ying, 103-124. Singapore: Asia Research Institute.

Lee, Gek Ling, (2005) Fasten your seat belts: Welcome to Singapore! Singapore: McGraw Hill Education.

Lee Gek Ling; Laina Ho, J.E. Lisa Meyer, Chitra Varaprasad and Carissa Young, (2003) Teaching English to students from China. Singapore: Singapore University Press.

Mackey, Alison; and Rita Elaine Silver, (2005) Interactional tasks and English L2 learning by immigrant children in Singapore. System 33, 239-260.

Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore, (2007) Economic Review Committee Reports. Executive Summary - Developing Singapore's Education Industry. http://app.mti.gov.sg (03/07/2008)

Morgan, D.L. (1997), Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. California: Sage Publications.

Pakir, Anne, (1999) Connecting with English in the context of internationalisation. TESOL Quarterly 33 (1), 103-114.

Portes, Alejandro and Min Zhou, (1993) The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530, 74-96.

Punch, K.F. (1998), Introduction to Social Research – Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. London: Sage Publications.

Purushotam, Nirmala, (2000) Negotiating multiculturalism: Disciplining difference in Singapore. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Stroud, Christopher, (2007) Multilingualism in ex-colonial countries. Handbook of multilingualism and multilingual communication, ed. by Peter Auer and Li Wei, 509-538. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Tan, Su Hwi, (2003) Theoretical ideals and ideologized reality in language planning. Language, society and education in Singapore: Issues and Trends. 2nd edition, ed. by S. Gopinathan, Anne Pakir, Ho Wah Kam and Vanithamani Saravanan, 45-64. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press.

Young, Carissa, (2003) “You dig tree tree to NUS”: Understanding Singapore English from the perspectives of international students. Teaching English to students from China, ed. by Lee Gek Ling; Laina Ho, J.E. Lisa Meyer, Chitra Varaprasad and Carissa Young, 94-106. Singapore: Singapore University Press.

Please check the Methodology for Teaching Spoken Grammar and English course at Pilgrims website.

|