Contemporary Understanding of the Reading Process and Reading Strategies Used by ESOL Learners While Reading a Written Discourse

Jacek Wasilewski, Poland

Jacek Wasilewski has been an EFL teacher for more than 20 years now. He is currently based at the University of Podlasie in Siedlce - Poland, where he works as an assistant at the English Studies Department. Current interests involve: discourse analysis, SLA, pragmatics, phonetics and phonology of an English Language.

E-mail: jackwas@interia.pl

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

The current view of the reading process

The schema theory

Schemata

The main models of reading processing

The bottom-up versus top-down reading model

The interactive model of reading

The primary reading strategy classification

Towards the broader categorization

Interaction through reading strategies

The perception of reading strategies

References

This paper sets out to shed light on the most important aspects referring to the reading process and strategies utilized by the readers of a foreign language when processing the written text. The first sections will go on to examine how the reading process is perceived in the field of contemporary English language teaching. The later sections concentrate on the existing theories concerning the reading processing and provide the classification of reading strategies. The final part refers to the perception of reading strategies and their role in a reading act.

An important issue in all stages of our education consists in improving the quality of learners’ outcomes. In reality, different factors affect these results. Among them one can find the quality of reading, the material used during lessons and seminars and the learners’ perception of value of the reading skills. Part of this perception may be a reflection of the previous stages of a learning process the students went through and another part is the effect of current training.

Over the last decade an explosion of research in the second language reading process including readers’ strategies has been observed. They have been of interest for what they reveal about the way readers manage their interaction with written discourse and what their relation is with text comprehension. This interest has been seen in the number of textbooks and educational and teacher prepared materials that are being published. The studies included various aspects as regards reading skills and focused e.g. on the reading strategies of successful and unsuccessful learners, individual differences and strategy use, the relationship with general language proficiency, strategy use among young learners and strategy use at tertiary level.

In general, the research suggests that learners whether engaged in secondary or university education have used a variety of strategies to help them with better comprehension, information storage and to simply become more efficient and effective readers. Strategies have been defined as learning techniques, behaviours or problem –solving tactics (Oxford 1990).

There are a number of reasons why the author of this paper has decided to focus on the process of reading and techniques used when working on a written text. The present review tends to heighten reading awareness among Polish learners of English. It is worth mentioning that their knowledge on reading itself and what it frequently involves is undoubtedly scant. This paper will attempt to foster independent learning and pro-active reading in secondary and higher education in Poland and will significantly contribute to better understanding and using strategies by Polish readers of English.

To fully understand the contemporary issues surrounding the reading process, a strong influence of the cognitive orientation, which considerably changed the perception of reading, should be emphasized. The new vision of reading as an important study skill was emphasized and supported by many researchers in the 1970’s. One of them worth mentioning was Kenneth Goodman (1967) who defined reading as receptive language process and used the metaphor of guessing game to describe a reading act. His psycholinguistic model of reading (later called the top-down model) began to have a big impact on views of L2 reading process.

The later studies on reading carried out, for example by Goodman (1988), Carrell (1988), indicates that reading is perceived as:

“an active process of comprehending where students need to be taught strategies to read more efficiently ( e.g. guess from context, define expectation, make inferences about the text, skim ahead to fill the context, etc “ . Furthermore, the same author, namely (Goodman , cited in Carrell and Eisterhold 1983: 554) by comparing reading to a “guessing game “, shows us that a reader becomes a message encoder.

Although one could agree with Goodman’s interpretation, his opponents (Weber 1984, Paran 1996:25) must not be forgotten because it shows that the opinions varied as regards the act of reading. Paran, for instance rejects such a view of reading specifying that all the sentences are never read in the same way. He argues that readers rely on different cue-words to get a gist of what kind of sentence may follow, whereas Weber states that the top-down reading processing can not account for all the needs of learners who are acquiring reading skills.

It has to be clarified that the earlier mentioned term the cognitive orientation and its widespread meaning in learning and teaching, compared to the previous theory called Behaviourism, was considered revolutionary in the 70s because it was defined as the activity of knowing: the acquisition, organization and use of knowledge. With reference to learning itself, it must be remembered that that it was seen as highly constructive process. As a contrast to the so called passive reader of the stimulus-response theory introduced by B.F Skinner (1957), a new type of reader was created who actively constructed meaning and became a strategic reader. In practice it meant using various techniques while processing a text which aided learners to better comprehend a written discourse.

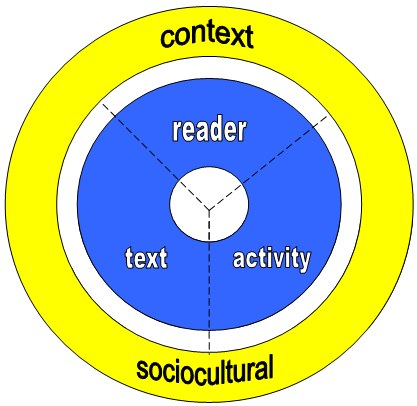

An important aspect of the reading process highlighted by researchers (Rumelhart, 1977; Stanovich, 1980) and worth considering is the occurrence of interaction among the reader, the text and the context.

The drawing below clearly shows that comprehension is a complex process which involves a mixture of elements depending on one another.

Figure 1

Source: Heuristic Thinking of Reading Comprehension by Rand Reading Study Group, (Snow 2002).

These components are as follows:

- the text

- the reader

- the activity-purpose of reading

It can be inferred from the diagram that comprehension in reading occurs as a relationship between the elements mentioned above and the sociocultural context in which the reading act occurred. It leads us to the conclusion that a full comprehension may be achieved if all these parts are interwoven. It may mean that a reader should take an active part in the process by interacting with a text and also reacting and responding to it in a multifarious way. Hence, it seems to be reasonable to agree with that a text interpretation may be varied depending on readers’ processing abilities and personal background knowledge.

Apart from the cognitive model that influenced the current understanding of the reading process, it appears that the concept of schema may also contribute to clarifying a reading action.

Generally speaking, schema theory is concerned with knowledge particularly with the way knowledge is represented in our minds and the importance of prior knowledge to learning something new. This theory is based on the belief that

“every act of comprehension involves one’s knowledge of the world as well “

(Anderson et al. in Carrell and Eisterhold, 1983: 73). Therefore, it can be stated that readers develop an interpretation of text through the interactive process of “combining textual information with the information a reader brings to a text “ (Widdowson in Grabe, 1988: 56 ) , as was shown in the above diagram.

The same reasoning may be supported by Ausubel who in his work entitled Educational Psychology (1968) puts forward the substantive approach:

“If I had to reduce all educational psychology to just one principle, I would say this: The most important single factor influencing learning is what the learner already knows. Ascertain this and teach him accordingly”.

The readers’ previously acquired knowledge emphasized by Ausubel is called schemata and seems to be of paramount importance in the act of reading. Given the fact that such knowledge may be obtained in different situations and various contexts enable us to assume that it is definitely varied. Schemata are components of the Schema Theory which are understood as organized structures where our knowledge is stored. According to Rumelhart (1980: 34), schemata constitute our knowledge about situations e.g. receiving guests, events e.g. going to a football game, actions e.g. doing shopping, and objects e.g. a house , a car, etc. One might also mention the fact that it is frequently called schematic knowledge which refers to scripts that people use to interpret the world. Since schematic knowledge is culture specific it is, therefore, easy to specify that it may play a major role in the right interpretation of a text. The term was precisely defined by Cook (1989: 69) as:

“mental representation of typical situation… used in discourse processing to predict the contents of the particular situation which the discourse describes “ .

Persuasive though the theory may seem, one is entitled to ask oneself whether schema really plays such a significant role in the reading comprehension.

The answer to this query can be found in numerous studies carried out by researchers. Carrell (1988b: 245), as one of them, for instance explains that:

“some students’ apparent reading problems may be the result of insufficient background knowledge “

If this may be the cause of problems during reading, it is necessary to emphasize that background knowledge including one’s previous experience is extremely helpful in the reading activity. Let us focus on the example which clarifies why this concept may be so beneficial during reading:

Suppose someone is reading a story and comes across the sentence,

“Joanna decided to stop at the local pub on her way home “

Immediately the schema for the pub (British) provides the reader with a wealth of information which may be accurate and interpreted adequately if readers are familiar with the background knowledge of the British pubs. Otherwise the comprehension may be distorted.

Granted that background knowledge and the heavy emphasis in reading lessons on pre-reading activities are widely accepted and popularized by influential methodology academics, (Aebersold, 1997, Alderson and Urquhart , Steffenson and Joag-Dev , cited in Hedge 2000 : 192 ) , we still have to remember that some researchers are of a different opinion. Stott (2001) for example although agreeing that pre-reading activities are beneficial in the act of reading, he also regards them as only partially useful. Janzen (2002) goes even further by accusing much of schema theory of being poorly developed by specifying that it has only a general meaning and is often presented metaphorically. The next section will focus on a more detailed explanation.

While on the subject of schema theory referred to above, it is worth pointing out that comprehending a text is an interactive process. This process can be divided into three models which include bottom-up, top-down and interactive processing.

The first model ( bottom –up ) used by readers while being involved in the act of reading considers the reading process as a text driven decoding process wherein the sole role of a reader is to reconstruct meaning embedded in the smallest units of text ( Gough 1972; Carrell 1988; McKoon and Radcliff 1992 ). Considering the text, it is viewed as a “chain of isolated words, each of which is to be deciphered individually “. Furthermore, Eskey, Carrell and Devine (1988) indicate that meaning is built up for a text from the smallest textual units at the bottom including letters and words to larger units at the top with phrases, clauses and links.

In contrast to the first model, it is necessary to refer to Goodman’s ( 1967) psychological process of reading later named the top-down or also known as inside-out processing. It needs to be stressed that this model began to wield a great impact on views of a second language learning (L2) in the seventies, in particular on conceptions about native and second language reading instruction. While bottom-up placed emphasis on the structure of the text, interestingly enough, the new model takes the opposite position that highlights readers’ interests, world knowledge and reading skills-strategies as the driving force behind reading comprehension. On balance, according to Goodman, readers are perceived as active participants who make predictions and process information

A commonly known and interesting explanation of reading processing which can be understood either as a distinction or a complementary combination is presented by Christine Nuttall (1996). In her book entitled “Teaching reading skills in a foreign language” the author draws our attention to the fact that the above-mentioned models may be treated by readers as a whole. Furthermore, she stresses that sometimes one model predominates over the other, but there are no doubts that both are needed to fully comprehend the text. Devine (1988) , however, argues that it may be of utmost importance to readers to strike a successful balance between bottoms-up and top-down for the interpretation of a written discourse.

The two images of processing presented metaphorically by Nuttall are shown below:

The pictures display an image of a readers’ approach towards reading comprehension. On the one hand they could be compared to an eagle with a good eye’s view that can see everything better from the top like in a top-down model: on the other hand readers should also be seen as meticulous scientists who examine the text carefully from the bottom like in a bottom-up processing.

Figure 2. Top-down processing

Source: Teaching Reading Skills in a Foreign Language (Nuttall.Ch.1996)

Figure 3. Bottom-up processing

Source: Teaching Reading Skills in a Foreign Language (Nuttall. Ch. 1996)

The use of only one model of reading in a first and second language became insufficient in the 1980’s. At that time it transpired that overreliance on one approach over the other might give rise to some problems with reading comprehension.

Numerous reading studies have recently revealed that it is really a disputable issue. In case of the top-down strategy, there seems to be an element of truth in the notion that the reader has an inadequate amount of knowledge for many texts as regards a reading topic and cannot generate predictions, (Stanovich 1980). The author strongly asserts that even a skilled reader can make predictions but unfortunately this takes him much longer than it would to recognise the words, phrases or links between the sentences or paragraphs. The argument against a superior role of the top-down view is also advanced by (Eskey 1988) who emphasizes some limitations of this processing. Namely, he considers this model as perfect for skilled and fluent English as a foreign language EFL/SL reader for whom perception and decoding have already become automatic. Unfortunately the top-down model of reading cannot be recommended for the less proficient or developing reader who might be, as generally accepted, more interested in developing grammatical skills such as cohesive devices and vocabulary recognition.

What is of paramount importance is the widespread belief accepted from native reading used by educators and English teachers that text content and word meaning can be derived from prediction, inference and guessing from the text. One is tempted to suggest that such reasoning should be avoided because it often relegates linguistic and lexical knowledge to a minor role. Chodkiewicz (2001) remarks that we cannot rely entirely on guessing meanings of words from context because our suppositions may be repeatedly incorrect. Taking one step further, Cobb (1999) seems to agree with this argument by adding that word knowledge appears to be a key ingredient and an important contributor to second language academic reading success. This belief is also supported by Hirsh and Nation (1992) who shows that to comprehend an academic text, a reader needs to know 95% of the words. This implies that a text is comprehensible only when there is no more that one unknown words every two lines.

Although it is true that the bottom-up model is regarded frequently as a substitute for high level processing; however, the fact remains that an important shortcoming of this model lies in its inadequacy which underestimates the contribution of the reader being responsible for prediction and processing information.

Considering the following sentence, (Wray & Medwell 1991; 98)

“If you aer a fluet reodur you wll hve no prblme reodng ths sntnce “

it could be clearly argued that comprehension of this line cannot be guaranteed by only a code cracking activity because there is something more to it than meets the eye: top-down strategies must be activated in order that the reader may find meaning in these codes. On the other hand, it is worth adding that the bottom-up model is satisfactory when we are taught vocabulary and an organization of a text but this gives us no assurance that the reader will be able to process the codes-words both rapidly and accurately when reading. It should also be emphasized that L2 readers are frequently panicked by unknown words in the text, so they stop reading to look new words up, thereby interrupting the normal speed and act of the reading process.

To overcome the problems the readers may encounter while reading in L2 and to properly achieve fluency and accuracy in reading , an effective solution would be created if foreign language readers relied on a symbiosis of top-down and bottom –up strategies. Hence, the interactive process assumes that skills acquired at different levels of language competence are best interactively available to process and interpret the written discourse. As Eskey (1988) claims, fluent reading entails both skillful decoding and relating information to prior knowledge. It seems therefore reasonable to add that readers become good decoders and interpreters of texts gradually but surely only when they are familiar with both lower- level processes , to name just a few, translation of written code or morphological processing and higher –level processes including activation of schemata or influence of attitude, motivation and reader interest

When talking about reading strategies, it is considered necessary to introduce the basic reading strategies (RS) classification. Much research has been done to identify and classify reading strategies in English language teaching (ELT) and it should be added that the study of successful learners in the learning process considerably contributed to gathering data regarding the most frequent actions taken by foreign language learners.

According to numerous studies that have been carried out on reading strategies and their influence on success in reading comprehension, there is a general consensus that the two contrastive groups identified by O’Malley and Chamot (1990) are the most basic orientation in the division of RS. The authors based mainly on cognitive psychology and used expert opinions and theoretical analysis of language tasks like reading comprehension. Their classification included the following types of strategies:

- COGNITIVE STRATEGIES, which deal with actual information, how to obtain it, inferring or deducing meaning from context, using dictionaries and grammar books, retaining information through memorization, repetition or mnemotechnic tricks.

- METACOGNITIVE STRATEGIES, which refer to self management, setting objectives, monitoring and self-evaluation are regarded by O’Malley as more significant to learners as they involve thinking about the learning process and planning for learning.

The same author, namely O’ Malley (1985: 561) tries to attach more importance to the second group by adding that:

“learners devoid of metacognitive approaches are learners without direction or opportunity to review their progress, accomplishments and future direction “ .

Such a primary role for the metacognitive strategies over the cognitive ones in the reading process has been shown in many studies on academic reading in L2. They indicate that metacognitive strategies play an important role in helping students plan and monitor their comprehension while reading (Li and Munby study (1996: 199-216), while other studies have demonstrated significant improvements in reading for rather poor learners who were trained in the use of these strategies (Block, 1992).

This belief is also shared by another educator named Flavell (1976: 232). According to him, metacognition refers to “one’s knowledge concerning one’s own cognitive processes and products “ while Block (1992 ) adds that metacognition is the ability to stand back and observe oneself .He further states that it is an ability often related to effective learning and to competent performance in any area of problem solving.

The wealth of studies conducted in the 1990s and in the early years of the twenty first century by researchers as regards strategies and vocabulary skills in reading (e.g. Carrell 1989, Grabe 1991, Block , Sarig and Olshavsky , quoted in McDonough 1995 , Urquart &Weir 1998) caused a great commotion over definitions of strategies per se. It may be sufficient to state that there has been the lack of consensus with respect to a clear categorization of reading strategies among methodologists.

It is partly due to the way the phrase “strategy “has been used and studied in different contexts both in the L1 and L2 language learning (Cohen 1998). In addition to that, it seems important to add that the words SKILL and STRATEGY frequently overlap and are used by researchers as the same notion. But in reality, it might be said that they are two different concepts.

The former refers to information processing techniques that are automatic. Skills are applied unconsciously and include expertise and repeated practice. In contrast, the latter are regarded as deliberately selected sensible moves learners may use in order to achieve goals e.g. during reading. It must be emphasized that strategies may become more efficient if they become automatised and are applied automatically as skills but this process may take a while before a strategy changes into a skill.

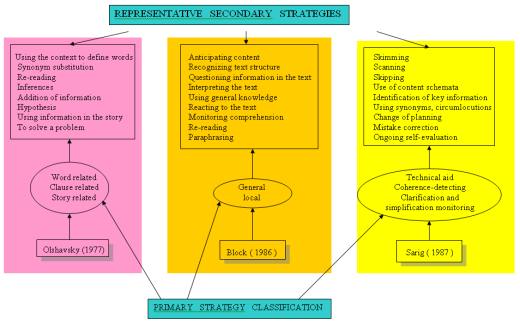

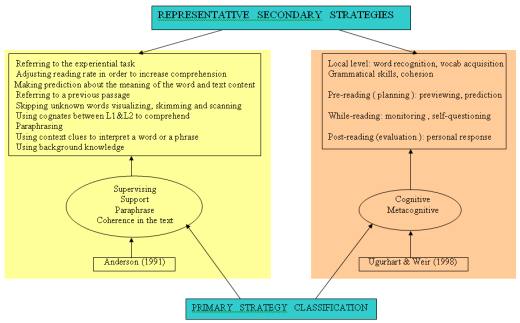

Let us focus on the broad classification drawn up by above cited researchers who carried out numerous studies on reading strategies.

Source: Strategy and skill in learning a foreign language (McDonough 1995)

As can be easily noticed from the diagrams, reading strategies have been going through a constant and term-making process. The strategies indicate that there is no consistency as regards similar-sounding strategies. It has to be stressed that what metacognitive scheme means to Weir does not have to signify the same to Block or Sarig.

Another important feature of reading strategies taxonomy is that they have always mentioned some category referring to words and their meanings such as identifying word meaning or simply words in context. Other researchers who also became deeply involved in identifying specialist skills in reading were Harmer (1991), Grabe (1991), McDonough (1995) and Chodkiewicz (2001).

One may simply notice that the classification is not free of its weaknesses. By looking at the Ugurhart and Weir’s scheme, there is no difficulty noting that this arrangement provides excellent goals for L2 teaching and testing and it could make a good and suitable plan for a typical reading comprehension activity lesson. But it appears that it might be criticized for such a reason that it tends to overemphasize psychomotor behaviour and ignore the type of processing used by novice readers.

There have been many attempts to identify the readers’ mental activities that are used in order to construct meaning from the text (Anderson et al.1991; Devine 1988a; Hosenfeld et al.1981). These activities are generally accepted as reading strategies or sometimes are referred to as skills. Garner (1987) defines them as an action or series of actions utilized by readers to formulate meaning. A similar interpretation of a strategy is presented by Phinney (1988:130) who compares strategies to a general plan of actions used by learners in the reading process.

It seems clear that L2 readers may find it difficult to comprehend various texts. To make things worse, if the texts become more professional like business or academic, the comprehension of reading may turn out to be a complete failure. Bearing these problems in mind, it has to be stressed that readers’ work could be facilitated by acquainting them with a variety of reading strategies. The question may arise:

Why are the strategies so helpful?

It is important to stress that a number of empirical studies have established a positive relationship between strategies and reading comprehension. It is essential to highlight at this point the action research conducted by Grover, Kullberg and Strawser (1999) who have found that the utilization of reading strategies and skills had a beneficial impact on students’ reading comprehension.

Their study entitled “Improving student achievement through organization of student learning “investigated various reading strategies to increase comprehension and vocabulary skills. The study focused on 3 elementary and one junior high school in the USA. The authors came to conclusion that poor reading comprehension and poor vocabulary skills contributed to lower student achievement. Such a poor performance was caused by several reasons that included limited English proficiency, low intellectual ability of students, disregard for learners’ individual learning styles or inability to make connections and insufficient reading skills. In addition to the above mentioned factors, the authors claim that a student’s failure to master general reading skills appears to be responsible for looking upon a reader as less skilled. Moreover, they are credited with the use of graphic organizers for the benefit of students’ achievement in literacy which referred to the development of reading comprehension and vocabulary knowledge. Their research finally determined that the technique used by Strawser (called graphic organizers, which means using a visual representation of knowledge such as knowledge maps, concept maps or story maps prior to reading longer passages), contributed to mastering critical vocabulary skills by 80 % at all levels of learners.

Apart from what has been said above regarding their study, it appears important to mention two significant assertions made by Phinney (op.cit. p.130) and Schwartz (1985: 199). The former claims that students frequently struggle without strategies to assist in the progression of reading while the latter places emphasis on vocabulary skills by saying:

“We need to teach students strategies they can use to expand their own vocab and to master unfamiliar concepts “.

Basically, reading strategies are believed to act as good signals of how learners approach reading tasks or solve problems encountered during the reading process. It could be said that they serve as pointers giving learners valuable clues about how to plan their work, tackle reading problems, assess the situation in reading or choose appropriate skills , techniques or behaviours in order to comprehend the text and learn something from it. In addition to that, metacognition, which is closely linked to the term of strategies, combines various thinking and reflective processes. For example, preparing and planning skills aid to improve students’ learning and thinking about their needs and accomplishments, which eventually enable them to become reflective readers. Also, the ability to be selective as regards the type of strategy in a given context allows learners to make conscious decisions about their learning process.

Another positive advantage coming from the use of strategies is monitoring one’s utilization of reading strategies.

A good argument for a valuable role the strategies play is an ability to orchestrate the use of more than one strategy during processing the text. This technique seems vital while reading academic or professional texts.

It is also worth mentioning that by evaluating the strategies and having an ability to ask the following questions:

- What am I trying to accomplish?

- What strategies am I using?

- How well am I using them?

- What else could I do?

learners have a chance to become independent and reflective readers.

However, our attention should be drawn to the fact that several studies indicate some limitations of reading strategies by stressing individual differences in learning styles.

Reid (1987), for instance suggests that some reading techniques may suit particular learning styles better than others and there is not a “one size fits all” bank of effective strategies. It happens that there are still a number of readers who like to be dependent on teachers and they never realize that they may hold responsibility for their reading tasks.

Another reasonable feature worth highlighting is that learning strategies including reading techniques and behaviours may be culturally specific. Such evidence has been provided by Mc Devit (2004) who specifies in her article that there are some countries where learning styles including reading strategies are well known and may be accepted with enthusiasm as an up to date way of teaching and learning. It usually refers to the western countries but on the other hand, in other areas in particular, Arab and Asian countries the implementation of reading techniques like (global ones) e.g. inferencing meaning from context, may turn out to be unfamiliar.

Research on reading strategies has pointed to an important aspect of this issue. It is widely supposed that reading comprehension is a sine qua non in academic learning areas. Besides, it is vital to professional success and to life long learning. Reviewing the developments in second language reading research, one has to mention Grabe (1991) who stresses the major importance of reading skills in academic reading contexts. Furthermore, Levine, Ferenz and Reves (2000) open up interesting areas when they state that:

The ability to read academic texts is considered one of the most important skills that university students of English as a second and foreign language ESL/EFL need to acquire.

Moreover, Shuyun and Munby (1996) share the belief and note that an academic reading is a very deliberate, demanding and complex process. In the light of this statement it may be accurate to specify that L2 students should be actively involved in the development of a wide repertoire of reading strategies which help them overcome difficulties when encountering comprehension problems.

Today there is a tendency to believe that expert readers use rapid decoding, large vocabularies, phonemic awareness, knowledge about text features and a variety of reading strategies to aid comprehension and memory. These skills usually refer to previously mentioned cognitive and metacognitive strategies which give a reader a chance to be successful and independent in the act of reading. However, it is necessary to point to differences in strategy use while reading. This question was investigated by (Anderson 1991 & Sarig 1987) who explain that “no two readers approach or process a written text in exactly the same way” If this is the case, then reading in L1 and other languages is of a highly individual nature. To take the argument further, one could claim that each reader uses different strategies if they are familiar with them. In addition to that, Harmer (1991) stresses the significance of individual factors influencing readers’ deduction of meaning from context. He refers to learning outside, learner needs and even the emotional attitude to some words in the text.

To sum it up, one must stress that the reading process does not seem to be easy to any L2 reader. The difficulty with understanding readers may have while processing the text largely depends on how they are prepared to tackle a written discourse. Reading simple texts ,for example with a short content and easy vocabulary does not require of readers to become experts but university level students must show their professional preparation and expertise in terms of their knowledge of problem solving techniques, reading strategies, wealth of lexis and their general approach towards the reading activity i.e. strategies.

Aebersold, J.A. & Field, ML (1997): From reader to reading teacher. Issues and strategies for second language classrooms. Cambridge : CUP.

Alderson, J.C. and Urquhart, A.H ( eds .), ( 1984) and Steffenson, M.S. and C. Joag-Dev (1984) cited by Hedge, T. ( 2000 ): Teaching and learning in the language classroom. Oxford: OUP.

Anderson, N.J. (1991): Individual differences in strategy use in second language reading and testing. Modern Language Journal, 75, ( p. 72-460).

Ausubel, D. (1968): Educational psychology: A cognitive view. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Block, E.L. (1992): See how they read: comprehensive monitoring of L1 and l2 readers. TESOL Quarterly, 26/2: (p. 43-319).

Block, Sarig & Olshavsky quoted in McDonough, S.H.(1995): Strategy and skill in learning a foreign language. London: Edward Arnold.

Carrell, P.L., Devine, J., Eskey, D.E., (eds.), (1988): Interactive approaches to second language reading. Cambridge: CUP.

Carrell, P.L. (1988b): “ Interactive text processing” Implications for ESL/second language reading classrooms. Cambridge:CUP.

Carrell, P.J. , & Eisterhold, J. (1988): Schema theory and ESL writing. Interactive approaches to second language reading, (p.73-92). Cambridge,UK: CUP.

Chodkiewicz, H. (2001): Vocabulary acquisition from the written context, Wydawnictwo UMCS, Lublin, (p. 299).

Cobb, P., & Bowers, J. (1999): Cognitive and situated learning. Perspectives in theory and practice. Educational Researcher 28 (2), (p.4-15).

Cohen, A. (1998): Strategies in learning and using a second language. London: Longman.

Cook, G. (1989): Discourse. Oxford: OUP.

Eskey, D. (1988): “Holding in the bottom”. An interactive approach to the language problem of second language readers in Carrell et. al (1988).

Flavell, J.H. (1976): Metacognitive aspects of problem solving. In L.B. Resnick (Ed), The nature of intelligence (p.231-235). Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Garner, R. (1987): Metacognition and reading comprehension. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex.

Goodman, K. (1967): Reading: A psychological guessing game. Journal of the Reading Specialist, 6, (p. 35-126 ).

Gough, P.B. (1972): One second of reading. In Kawanagh, J.F. & Mattingley, I.G.( Eds.),Language by ear and by eye, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Grabe, W. (1991): Current developments in second language reading research. TESOL Quarterly, 25, 3, (p. 375-406).

Grabe, W. (1988): “Reassessing the term interactive” in Carrell, P.L.. , Devine, J. and Eskey, D.E. (eds.). (1988). Interactive approaches to second language reading: CUP.

Grover, S., Kullberg, K., Strawser, C. (1999): Improving student achievement through Organisation of student learning. International Educational Journal, vol.5,No. 4, (2004).

Harmer, J. , & Rossner, R. (1991): More than words. Vols. 1, 2. Harlow: Longman.

Hirsh, D. and Nation, P. (1992): What vocabulary size is needed to read unsimplified texts for pleasure? Reading in a foreign language. (8), 2: (p.689-696).

Hosenfeld, C., et. al (1981): Second language reading. A curricular sequence for teaching reading strategies. Foreign Language Annals, 14, 5, (p.22-415).

Janzen, J. (2002): Teaching strategic reading. In Richards&Renandya (2002): (p.287-294).

McDevitt, B. (2004): ELT Journal, vol 58/1.OUP.

McDonough, S.H. (1995): Strategy and skill in learning a foreign language. London: Edward Arnold.

Mckoon, G.&Radcliff, R. (1992): Interference during reading. Psychological Review, 99,(p.440-460).

Nuttall, Ch. (1996): Teaching reading skills in a foreign language. Macmillan-Heineman.

O’Malley, J.M., Chamot, A.U., Stewner-manzanares, G., Russo, R.P., Kupper, L. (1985): “ Learner strategy application with students of English as a second language” TESOL Quarterly 19/3 (p.557-584).

O’Malley, J.M., & Chamot, A.U. (1990): Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge, UK: CUP.

Oxford, R. (1990): Language learning strategies. Heinle&Heinle Publishers.

Paran, A. (1996): Reading in EFL: Facts and Fictions. ELT Journal, 5(1), (p.25-34).

Phinney, M. (1988): Reading with the troubled reader (ch.2). Portsmouth, NH: Heineman.

Reid, J. (1987): “The learning style preferences of ESL students”. TESOL Quarterly 21/1 (p.179-185).

Rumelhart, D. (1980): “Schemata: the building blocks of cognition “. Theoretical issues in reading comprehension. Hillsdale,NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Sarig,G. (1987): High level reading in the first and in the foreign language. Some comparative process data. In Devine, J. et. al (eds.). (p.20-105).

Schwartz, R.M. & Raphael, T.E. (1985): Concept of definition: A key to improving students’ vocabulary. The Reading Teacher, 39 (2), (p.198-205).

Skinner, B.F. (1957): Verbal Behaviour. New York:Appleton-Century Crofts.

Shuyun, L. & Munby, H. (1996): Metacognitive strategies in second language academic reading: A qualitative investigation. English for Specific Purposes, 15 (3), (p.199-216).

Snow, C. (2002): Reading for understanding: Toward a R&D programme in reading comprehension. Rand Research Brief: www.rand.org/multi/achievement ( Retrieved

on January 15,2007).

Stanovich, K.E. (1980): “Towards an interactive-compensatory model of individual differences in the development of reading fluency “ In Reading Research Quarterly 16, (p.32-71).

Stott, N. (2001): Helping ESL students become better readers: Schema theory applications and limitations. The internet TESL Journal, vol. VII,No.11,http://iteslj.org./Articles/Stott-Schema.html (accessed on December 29, 2006).

Urqurhart, S. and Weir, C. (1998): Reading in a second language: Process, product and practice. Longman.

Weber. R.M. (1984): Reading: United States. Annual review of applied linguistics 4, (p.111-123).

Wray, D., & Medwell, J. (1991): Literacy and language in the primary years. London: Routledge.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the From Teaching to Training course at Pilgrims website.

|