Young Learners’ Learning Styles in Magic Book I and Magic Book II: Mission Accomplished?

Marina Mattheoudakis and Thomai Alexiou, Greece

Marina Mattheoudaki is a tenured Associate Professor at the Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, School of English, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. She holds an M.A. in TEFL from the University of Birmingham, U.K. and a Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Her main research interests lie in the areas of second language acquisition and teaching, CLIL, corpora and their applications.

Thomaï Alexiou is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, School of English, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Her expertise is on early foreign language learning, methodology of teaching languages and material development for very young learners. She has also authored and edited textbooks for children learning English as a foreign language.

Menu

Introduction

The English for Young Learners Project

Learning styles and young learners

Magic Book 1 and Magic Book 2: Choices and innovations

Learning styles in the Magic Books

Results and discussion

Conclusion

References

Appendix I: Magic Book 1

Appendix II: Magic Book 2

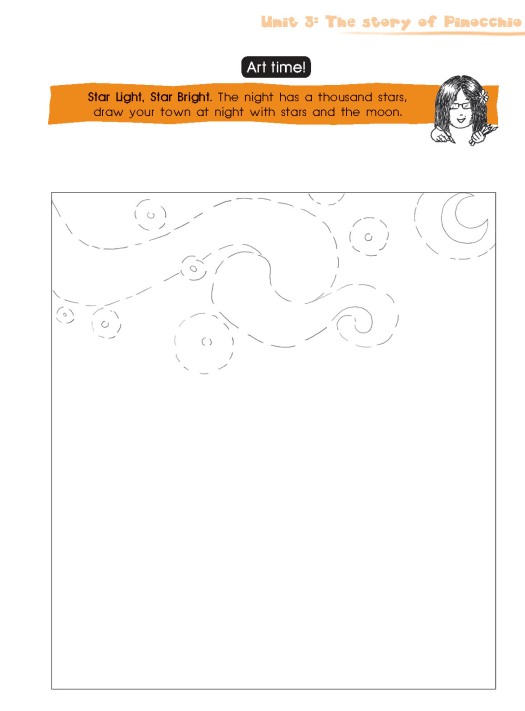

Appendix III: Art Time

The present paper aims to investigate the learning style profile promoted in Magic Book 1 and Magic Book 2 (henceforth MB1 and MB2), the EFL coursebooks developed for 8-9-year-old learners in Greek state schools. This is an innovative study because it focuses on young learners’ learning styles as these are approached and developed through the tasks and activities of the aforementioned EFL course books. The impetus stemmed from the fact that the issue of catering for learners' learning styles in EFL materials has been scarcely researched; yet, it has been claimed that matching learners’ learning styles and teaching approaches can facilitate foreign language acquisition and make the learning procedure enjoyable and stress-free (Felder & Silverman, 1988; Felder & Henriques, 1995; Peacock, 2001). The importance of learning styles in the learning process is similarly reflected in the observations of educationalists for the need to adapt any teaching material in a way that addresses learners’ learning styles (Charalambous, 2011).

In the present study we will investigate whether there is a balance between visual, auditory and kinaesthetic (VAK, as proposed by Stirling, 1987) activities in the two books and discuss the importance of promoting multimodal teaching. Before doing this though, we intend to present the two coursebooks and provide a comprehensive and sound rationale for the choices made in authoring them. As the books break new ground in the area of teaching English to young learners, their most important innovations are discussed; their didactic and pedagogical aims are analysed so as to allow a better understanding of how we tried to target Greek early EFL learners’ interests and needs.

Magic Books 1 and 2 have been designed and created under the English for Young Learners –EYL project (http://rcel.enl.uoa.gr/peap/en) within the framework of the National Strategic Reference Frameworks (NSRF) Programme: co-financed Act “New Policies of Foreign Language Education at Schools: English for Young Learners” (http://rcel.enl.uoa.gr/peap/en). The whole project was under the supervision and coordination of the scientific coordinator, Professor Bessie Dendrinos of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

The EYL project aimed to intensify English language instruction in Greek state primary education and introduce, on a pilot basis, the teaching of English to first and second grade learners in about 1,000 primary schools in Greece. The project also financed the authoring of two coursebooks for 3rd grade learners, Magic Book 1and Magic Book 2, both edited by Alexiou and Mattheoudakis (2012, 2014, respectively). The editors also contributed to the writing of the book together with a team of experienced primary school English language teachers. Magic Book 1 specifically targets the needs of 3rd graders who have never received English language instruction before, while Magic Book 2 addresses learners of the same grade who have already been exposed to EFL in the first and second primary school grades within the EYL project; these are learners attending one of the aforementioned 1,000 primary schools. Although English was previously taught to third-graders, the coursebooks selected and used at schools were commercial ones and sometimes unsuitable for the Greek state educational context.

Learning styles have been extensively discussed in the educational psychology literature (Claxton & Murrell, 1987; Schmeck, 1988) and, especially, in the context of language learning (Oxford, 1990; Oxford & Ehrman, 1993; Wallace & Oxford, 1992).

Several definitions have been provided for the term ‘learning style’. Keefe (1979), for example, defines learning style as “the characteristic cognitive, affective and physiological behaviours that serve as relatively stable indicators of how learners perceive, interact with and respond to the learning environment” (p. 4). Reid (1995) argued that learning style is an individual’s natural, habitual, and preferred way of absorbing, processing, and retaining new information and skills, and more recently, Sternberg, Grigorenko and Zhang (2008) defined styles “as individual differences in approaches to tasks that can make a difference in the way in which and, potentially, in the efficacy with which a person perceives, learns, or thinks” (p. 486).

There are several different approaches to the classification of leaning styles. One approach is based on personality psychology. Myers and Briggs developed a personality inventory (MBTI), which contributes four dimensions to learning style: extraversion vs. introversion, sensing vs. intuition, thinking vs. feeling, and judging vs. perceiving (Myers & McCaulley, 1985). Another approach is represented by Kolb’s Inventory (1976) which focuses on abilities we need to develop in order to learn and is based on a four-stage cycle of learning: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. A further model of learning styles was designed by Rita Dunn and Kenneth Dunn and is based on five major domains (environmental, emotional, sociological, physiological, and psychological) (Oxford, 2003). Another model of learning styles was developed by Fleming (2010) who distinguished four sensory modalities that students prefer to use when learning: Visual, Auditory, Reading/writing preference, and Kinaesthetic or Tactile (known as VARK, VAKT or, more commonly, as VAK). These preferences are usually combined, with one or two of them being the dominant ones. Visual learners learn more effectively through the visual stimuli, auditory learners acquire information more effectively through hearing, while learners with reading and writing preference use the printed word as the most important way to convey and receive information. Finally, kinaesthetic learners learn more effectively through concrete body experience and touch. Kinaesthetic learners use all their five senses in order to learn, i.e., sight, taste, smell, touch and hearing, and are connected to the reality “either through experience, example, practice, or simulation” (Fleming & Mills, 1992, p. 141).

Every person, learner or teacher, has a particular learning style profile but learning styles are not stable and unchanged forms; they can be modified according to the task (Oxford, 2011), and learners, in particular, are advised to “stretch” their learning styles so that they can enrich their learning style profile, adapt and cope in a variety of learning situations. Researchers have claimed that learning styles do affect student learning since they found significant relationships between multiple learning styles and student achievement (Friedel & Rudd, 2006).

Learners’ learning styles may depend on several factors, such as culture (Hofstede, 1986; Reid, 1987), previous learning experiences (Reid, 1987), educational background (Peacock, 2001), language background, gender, age, level of education (Reid, 1987), and even socio-economic status (Mattheoudakis & Alexiou, 2010).

Various research studies in EFL and learning styles have concluded that learning styles are ‘value-neutral’; consequently, no one style is better than others (Arnold, 1999, p. 302). In support of this claim, Rudd, Baker and Hoover (2000) found no relationship between learning styles and critical thinking or intelligence. What has also been found is that although learning styles are described as opposites, they should actually be seen as existing and developing on a continuum (Arnold, 1999).

Although there is no particular teaching or learning method that can suit the needs of all learners simultaneously, it has been argued that appropriate teaching techniques can accommodate different learning styles (see also Evans & Sadler-Smith, 2006). With reference to teaching styles and learners’ achievement, it has been claimed that matching the learning styles of students in a language class with the teaching style of the teacher can have a positive impact on the quality of learners’ learning, and, especially, on their motivation and attitudes toward the class and the subject (Felder & Henriques, 1995; Felder & Silverman, 1988; Oxford, 1999; Peacock, 2001; Wesche, 1981;). In this respect, the use of teaching material and of coursebooks, in particular, should be expected to have an impact on learners’ learning styles. To date, research in this field is lacking and, therefore, very little is known about the potential impact of coursebooks on student’s learning styles. An exception is Šímová’s (2011) recent attempt to chart the learning style profiles of three EFL coursebooks for young learners in the Czech Republic.

With respect to young learners, in particular, it is worth noting that although instructed L2 acquisition by children has been the focus of much research interest in the last twenty years (Edelenbos, Johnstone & Kubanek, 2006; Nikolov, 2009, Pinter, 2011), their learning styles have been scarcely researched. Vincent (2001) claimed that a significant number of primary school children are mostly visual, yet Dunn, Dunn and Perrin (1994) suggest that most 5 to 8-year-old learners are tactile and kinaesthetic. A previous case study in Greece (Mattheoudakis & Alexiou, 2010) indicated that the vast majority of Greek young learners are mainly visual and kinaesthetic. A comparison was made between three different age groups of students (10, 11, 12 years old) and results indicated that older learners are mainly kinaesthetic while younger ones prefer mainly visual stimuli. The main conclusion, however, was that learners tend to use different learning styles for different learning purposes. For example, when they learn how to read, they may use mainly the visual and auditory modalities, whereas in vocabulary learning they may resort to the kinaesthetic modality, especially if the word is concrete (e.g., tree).

In the present study we are going to focus on the learning style profile of two EFL coursebooks (Magic Book 1 and Magic Book 2) written for young learners in Greece. For the purposes of our study, we are going to make use of the VAK learning style model as developed by Stirling (1987). In particular, we are going to explore whether the two books promote a balanced proportion of VAK styles; catering for a variety of learning styles at this age and stage of L2 learning is particularly important assuming that young learners’ learning styles tend to be more varied, flexible and adaptable (cf. Oxford, 2011) and that age and schooling are expected to play in important role in shaping their styles. The design of an EFL coursebook with a balanced learning style profile might also safeguard learners by ensuring that teachers will not unduly focus on and teach mostly according to their own modality preferences. A coursebook catering for a variety of learning styles may also prove particularly useful for inexperienced teachers who are commonly expected to prioritize different issues in their teaching practice.

The study

The present study aims to (a) expose the rationale behind the methodological choices made in MB1 and MB2, and (b) investigate whether MB1 and MB2 cater for the VAK styles, as defined by Stirling (1987). In particular, the research questions are:

(a) Do MB1 and MB2 relate to the needs and interests of Greek young learners studying EFL at school?

(b) Is there a balance of VAK styles in the activities used in the pupil and activity books of MB1 and MB2?

In order to answer the first research question, the rationale behind choices made in the two coursebooks will be provided. As for the second research question, we listed all activities in the Student’s and the Activity book of both MB1 and MB2 and categorised them according to the VAK model.

(a) Do MB1 and MB2 relate to the needs and interests of Greek young learners studying EFL at school?

Magic Book 1 and Magic Book 2 address Greek learners of English in the 3rd grade of primary school (8-9 years old). The former is written for learners who have not had any prior exposure to English, whereas the latter addresses learners who have attended English classes in the first and second grades of primary school.

The teaching materials include:

(i) Coursebooks Magic Book 1 and Magic Book 2

(ii) Activity books Magic Book 1 and Magic Book 2

(iii) A Teacher’s book for each coursebook

(iv) 2 CDs with the sound files of the texts and activities

There are also resource materials with karaoke, animated videos, extra activities (memory games, puzzles), and interactive flipbooks. These are supplementary and differentiated materials accessible on line.

Both books share a similar structure: MB 1 consists of 8 units and MB 2 consists of 10. Recall that MB1 addresses beginners whereas MB2 targets 3rd graders who have previously attended English classes for two years in grades 1 and 2; thus the latter are expected to be familiar with at least some vocabulary items and structures and therefore able to deal with more material. Each unit consists of three (3) lessons and introduces a different story. MB1 and MB2 are innovative English language coursebooks whose rationale and content differ significantly from those commonly found in commercially available coursebooks of this level. The books introduce a new ‘mentality’ to the way English should be taught at the early stages of L2 learning.

The most important and innovative elements of the books, both for the Greek context but also beyond this, pertain to the fact that all choices related to the teaching material, the language selected and the teaching methodology supported are research-based; the books combine a strong pedagogical orientation with recent research findings related to foreign language acquisition and to young learners’ cognitive and language development (Alexiou & Mattheoudakis, forthcoming). Both coursebooks are process- rather than product-oriented; this means that they focus on how children learn and not on how much they can achieve. Further innovative features include the contextualized learning of lexical chunks, phonics-based teaching of reading, implicit teaching of grammar, development of cognitive skills, alternative types of assessment, organic integration of arts, use of cross-curricular links, use of yellow background for the reading texts to facilitate reading for dyslexic learners.

Additionally, the teaching framework selected for the writing of both coursebooks is story-based. Narration and storytelling constitute the basic techniques deemed appropriate for this age group, as children are already familiar with the narrative context of stories in their mother tongue. Stories enrich the learning process, cultivate imagination and constitute a shared social and multicultural experience (Ellis & Brewster, 2002). The thematic areas covered in the books have been carefully selected to match the needs and preferences of the target age group. At the same time, relevant research into the themes and topics included in young learners’ coursebooks (Alexiou & Konstantakis, 2009) was taken into consideration when choices regarding the themes of the books had to be made. Most stories (e.g., the fables of Aesop, The animal school) are of moralizing character aiming to serve both linguistic and pedagogical objectives.

The use of stories facilitates the acquisition of vocabulary and, in particular, of lexical chunks. Both books place particular emphasis on the teaching and learning of lexical chunks. Psycholinguistic research evidence suggests that lexical phrases are processed more fluently than openly constructed language (Ellis, Simpson-Vlach, & Manyard, 2008). Similarly, Lewis (2002) argues that lexical phrases and chunks are easier to learn because it is easier to deconstruct a chunk than to construct it. Thus, by prioritizing the learning of lexical phrases and chunks, we actually enable young learners to become efficient listeners and fluent speakers.

Ellis (2005) has pointed out that formulaic expressions (lexical phrases and lexical chunks) may serve as a basis for the later development of a rule-based competence. Taking Ellis’ point into consideration, we employed the use of formulaic language, e.g., this is our classroom, plant a tree, friends don’t fight, etc. in order to implicitly teach several grammatical structures appropriate for the learners’ current stage of language proficiency. Of course, the teaching aim in the cases above is not the explicit teaching of the corresponding structures (e.g., the possessive adjectives, the imperative form, or negation), but learners’ ability to comprehend their semantic content and use them in discourse. In fact, nowhere in the book can one find explicit presentation of grammatical structures and this choice was dictated by (a) learners’ age and ensuing lack of metalanguage and analytic skills, and (b) our firm belief that lexical phrases and formulaic expressions can be used to introduce grammatical phenomena and structures that are conventionally treated as part of grammar (cf. Lewis, 1993, 2002).

As drilling, rote learning and decontextualized memorization are not encouraged anywhere in the book, other techniques had to be promoted so as to allow learners practise and eventually acquire the formulaic language. To this aim, a variety of activities were designed, inspired by the plot of each story. These activities recycle the formulaic language and structures presented through it in playful and meaningful ways, not only within the same unit but also, and more importantly, from one unit to the next or even after several units.

With respect to vocabulary selection, several criteria were taken into consideration when selecting vocabulary to include in MB1 and MB2. One criterion was the appropriacy of words and thematic areas; these were related to young learners’ interests and daily life activities. Another criterion was the imageability of the lexical items selected; thus, concrete rather than abstract lexical items were included as these are considered to be appropriate for young learners’ cognitive level, they are easier to visualize, and consequently internalise and recall. Finally, frequency issues were taken into account: priority was given to highly frequent words as these are expected to enable learners to comprehend and start producing vocabulary that is commonly encountered in everyday situations and thus to communicate effectively. To this aim, the English Vocabulary Profile (EVP) was taken into consideration as well as Nation’s frequency word lists.

Although there is a homogeneous structure throughout the books, there is a variety of activities from one lesson to another (e.g., mazes, decoding games, problem-solving activities, puzzles, etc). The focus is first on receptive and then on productive skills: there is actually a gradual transition of emphasis from receptive to productive skills and, more particularly, from oracy to literacy. Thus, first children listen, then they speak, later they read and finally they write. The learning outcomes focus on fluency in oral communication at a basic level as well as on the ability to understand and respond to aural input which concerns simple everyday language: for socializing, talking about school, children’s activities, food and healthy habits, seasons, weather and clothes, helping people and caring for the environment. Children are also expected to develop basic literacy skills and the ability to recognize and read items and lexical chunks they have been orally taught. The goal is to increase language input and output in the classroom and the ultimate aim of the book is to provide opportunities for holistic development of young learners within a stimulating and enjoyable context.

Naturally, the above decisions led us to the choice of particular tasks and activities: some of them aimed to facilitate word comprehension and retention through visual stimuli or physical movement, others promoted the development of listening comprehension, and still others the development of reading and writing skills.

(b) Is there a balance of VAK styles in the activities used in the pupil and activity books?

In order to address this research question, we counted all activities in all four books, namely Magic Book 1 Student’s book, Magic Book 1 Activity book, Magic Book 2 Student’s Book and Magic Book 2 Activity Book.

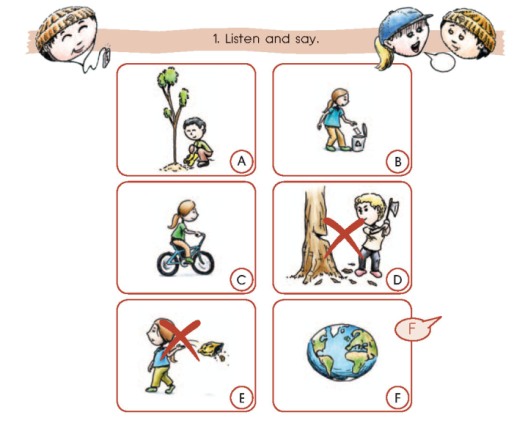

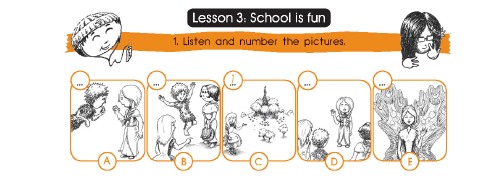

In order to explain how we identified each learning style, we provide an example of each. Figure 1 shows what we perceive as a visual style activity, Figure 2 is a sample of an auditory style activity and Figure 3 represents a kinaesthetic one. However, in some cases, like the activity shown in Figure 4, a combination of styles was catered for; the particular activity was thus categorized under the respective styles (in this case, auditory and visual).

Figure 1: Visual activity

This activity requires learners to identify the characters of the story hiding behind the trees; this is clearly a visual activity requiring perception and observation skills.

Figure 2: Auditory activity

The activity in Figure 2 is an auditory activity that requires learners to listen to lexical phrases – already introduced in the lessons – and match them with the corresponding pictures. The particular activity aims to promote their listening comprehension skills.

Figure 3: Kinaesthetic activity

In this activity (Figure 3) learners are asked to use their body in order to follow particular commands by performing an action; this is clearly a kinaesthetic activity commonly known as ‘Simon says...’.

Figure 4: An auditory and visual activity

In several cases, like the one above, we addressed a combination of learning styles within one activity. In this activity learners need to listen to and at the same time look at the pictures to decide which the correct picture is, according to what they hear.

The coursebooks also include activities that do not belong to the VAK learning style model, e.g., ‘Talk to your partner about your food preference’. Similar activities promote interaction and communication among learners while other activities (e.g., projects) aim to foster communication and peer cooperation.

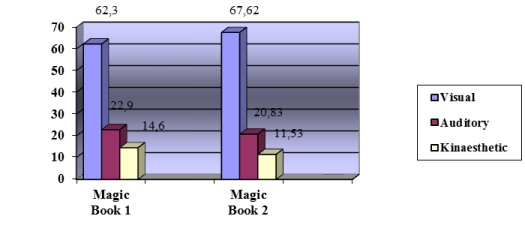

On the basis of the categorisation of the activities, as this has been exemplified above, the following table illustrates the learning style profile of Magic Books 1 and 2 – student and activity books.

| Visual | Auditory | Kinaesthetic | Total |

| Magic Book 1 | 175 | 62,3% | 64 | 22,9% | 41 | 14,6% | 280 |

| Magic Book 2 | 211 | 67,62% | 65 | 20,83% | 36 | 11,53% | 312 |

Table 1. Categorisation of activities in MB1 and MB2 according to the VAK model

Figure 5. Categorisation of activities in MB1 and MB2 according to the VAK model

The first finding concerns the total sum of the activities included in the two books. Overall, MB2 includes a larger number of activities compared to MB1 but this is to be expected as MB2 includes two more units than MB1. Interestingly enough, visual activities are prominent in both books, while auditory and, especially, kinaesthetic activities are considerably fewer. In MB2 the predominance of visual activities is even more obvious, while auditory and kinaesthetic activities are even fewer than those in MB1. If we take into account previous research findings which indicate that the majority of learners (40%) prefer learning visually (Reid, 1987), then the choice to include so many visual activities is quite plausible. Our emphasis on the use of visual activities is also related to our choice to provide opportunities to young learners to relate newly taught words or lexical phrases to the corresponding visual input; as already mentioned, most vocabulary items chosen for this level are concrete words and thus imageable; the use of visual activities exploits this imageability.

Findings similar to ours were noted by Šímová (2011) in her research into three EFL coursebooks for 3rd graders in the Czech Republic as well as by Palmberg (2002). In Šímová’s study there was a greater balance between visual and auditory activities but kinaesthetic style was similarly under-represented. Šímová points out that visual and auditory activities are much more frequent than kinaesthetic ones and stresses the need for more activities to accommodate kinaesthetic learners. She attributes this finding to the fact that the authors of the particular coursebooks tried to cater for the development of language skills - viz., listening and reading - that need to be practised in the English class and that is why they provided more auditory and visual activities. Palmberg’s findings concern a particular coursebook used in Finland in which kinaesthetic activities represent only 5% of the total sum of the book activities (his categorisation followed Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences model (1983, cited in Palmberg, 2002)). Palmberg claimed that this may also be related to the intelligence profiles of the writers of the coursebook, whether intentionally done or not.

On the basis of our findings, one might claim that auditory and especially kinaesthetic learners who are taught English with MB1 or MB2 are at a disadvantage as they do not have as many opportunities as visual learners to practise English through their preferred modality. With respect to the auditory activities, in particular, their importance should not be underestimated as they provide learners with practice in listening comprehension and exposure to native speaker input. However, when writing a coursebook, writers need to take into consideration space and time constraints related to the book but also to actual teaching time. In order to cater for the auditory 3rd graders, we designed alternative materials, such as flipbooks with audio material as well as songs. This material – which is accessible on line – may be used in class but also at home by learners themselves should they wish to practise or play. Similarly, for kinaesthetic learners we included in each unit a separate section called ‘Art time’ (see Appendix III) as well as Projects (see Figure 6). These supplementary activities aim to cater for kinaesthetic learners by providing opportunities for drawing, cutting, painting, preparing posters and generally working with arts and crafts. Taking into account the importance of a multi-sensory approach to learning, especially at this age, we tried to balance the proportion of the three types of activities (visual, auditory, kinaesthetic) by providing such supplementary material electronically. However, we did not include these activities in the categorisation of the activities above, as they are not part of the compulsory teaching material and, therefore, may not always be used by the EFL teachers. In fact, they may never be used if the teacher chooses not to use them or if the school does not provide access to computers.

Figure 6: Sample of Project

Our choice to include activities like the ‘Art time’ in the MBs was also based on findings of a previous study of ours (Mattheoudakis & Alexiou, 2010) into young learners’ learning styles. In particular, one of these findings related to the limited kinaesthetic approaches adopted in the Greek school context, as Greek teachers focus on linguistic and mathematic skills and thus encourage practice of visual and auditory styles while neglecting learners’ kinaesthetic preferences. Such teaching choices may be attributed to Greek teachers’ preferences for conventional and traditional teaching techniques but they often create a mismatch between learner preferences and the teaching methodologies adopted, especially in the case of young learners (cf. Oxford, 1999).

Even though we were aware of the need to boost the kinaesthetic profile of the coursebooks and provided several opportunities to young learners to develop their kinaesthetic and tactile preferences, the outcome achieved was not balanced. The major reason for this imbalance, which favours mainly visual learners and which is similarly found in other coursebooks, may be the predominance of visual input as a quick and effective technique for teaching vocabulary. Also, it may be related to coursebook writers’ concerns about the feasibility of certain kinaesthetic activities within the limited space of a classroom. Lastly, we should also consider the possibility of the learning style profile of the book reflecting, to a certain extent, the personal learning style(s) of the cousebook writers (cf. Palmberg, 2002). This is relevant to the observation that teachers’ teaching choices are often influenced by their own learning styles.

The present paper focused on MB1 and MB2, the two EFL coursebooks developed for 3rd graders in Greek state primary schools. In particular, we elaborated on the rationale behind the teaching material, techniques and language choices in MBs and argued that the development of both coursebooks is based on findings of relevant research in young learners and second language acquisition. In the present paper we also aimed to chart the learning style profile of MBs; the results of this study indicated that there is a notable imbalance in the activities of the books with respect to the learning styles addressed. In particular, both coursebooks seem to accommodate mostly visual learners and to a much smaller extent auditory and kinaesthetic ones. We argued that this predominance of visual modality activities may be attributed to the effectiveness of visual stimuli within the foreign language teaching context but also to constraints imposed both by coursebooks and actual teaching time. The inclusion of arts and crafts materials in the activity books (e.g., the ‘Art time’, the Projects) as well as the rich array of kinaesthetic, auditory and mixed-modality activities electronically available aim to compensate for this imbalance. We are aware of course that the very nature of this material – being supplementary – means that teachers may easily ignore it and skip it. At the same time, the use of electronic material requires access to computers, which may not be possible in some geographically remote schools. However, as young learners are considered ‘digital natives’, access to computers and use of online materials are a sine qua non in classroom teaching and should be amply provided for.

The development of balanced EFL teaching materials which address learners with different learning modalities should be an achievable target. However, such materials should be developed both in print and electronically. The systematic use of different modes of teaching is probably necessary in order to address different channels of perception.

Alexiou, T., & Konstantakis, N. (2009). Lexis for young learners: Are we heading for frequency or just common sense?’ In A. Tsangalidis (Ed.), Selection of papers for the 18th symposium of theoretical and applied linguistics (pp. 59-66). Thessaloniki: Monochromia Publishing.

Alexiou, T. & M. Mattheoudakis, M. (2012). Magic Book 2. Athens: Ministry of Education,

Religious Affairs, Culture and Sport.

Alexiou, T. & Mattheoudakis, M. (2014). Magic Book 1. Athens: Computer Technology Institute and Press ‘Diophantus’.

Alexiou, T., & Mattheoudakis, M. (forthcoming). A paradigm shift in EFL material development for young learners: Instilling pedagogy in teaching practice. In C. N. Giannikas, L. McLaughlin, N. Deutch, & G. Fanning (Eds), IATEFL Young Learners

and Teenagers SIG. Garnet Publishing.

Arnold, J. (Ed.). (1999). Affect in language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Charalambous, A. C. (2011). The role and use of coursebooks in EFL. Unpublished MA dissertation.

Claxton, C. S., & Murrell, P. H. (Eds.). (1987). Learning styles : Implications for improving education practices. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 4. Washington, DC: Association for the study of Higher Education.

Dunn, R., Dunn, K., & Perrin, J. (1994). Teaching young children through their individual learning styles: Practical approaches for grades K-2. Boston, MA: Pearson Allyn Bacon Prentice Hall.

Edelenbos P., Johnstone R. & Kubanek A. (2006) The main pedagogical principles underlying the teaching of languages to very young learners: Languages for the children of Europe. Published Research, Good Practice & Main Principles, SUMMARY (Final Report of the EAC 89/04, Lot 1 study). www.poliglotti4.eu/docs/Main_Pedagogical_Principles_ELL.pdf

Ellis, R. (2005). Principles of instructed language learning. Asian EFL Journal, 7(3), 9-24.

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (2002). Tell it again! The new storytelling handbook for primary teachers. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

Ellis, N. C., Simpson-Vlach, R., & Manyard, C. (2008). Formulaic language in native and second-language speakers: Psycholinguistics, corpus linguistics, and TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 41(3), 375-396.

Evans, C., & Sadler-Smith, E. (2006). Learning styles. Education and Training (Special Issue), 48(2 & 3), 77-83.

Felder, R. M., & Silverman, L. K. (1988). Learning and teaching styles. Engineering Education, 78(7), 674-681.

Felder, R. M., & Henriques E. R. (1995). Learning and teaching styles in foreign and second language education. Foreign Language Annals, 28(1), 21–31.

Fleming, N. D., & Mills, C. (1992). Not another inventory rather a catalyst for reflection. To Improve the Academy, 11(246), 137-155. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1245&context=podimproveacad

Fleming, N. (2010). The VARK questionnaire (2001-1010). Retrieved from

www.vark-learn.com/english/page.asp?p=questionnaire

Friedel, C., & Rudd, R. (2006). Creative thinking and learning in undergraduate agriculture students. Journal of Agricultural Education, 47(4), 102-111.

Hofstede, G. (1986). Cultural differences in teaching and learning. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, (11), 301-320.

Keefe, J. W. (1979). Learning style: An overview. In J. W. Keefe (Ed.), Student learning styles: diagnosing and prescribing programs (pp. 1-17). Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Kolb, D. A. (1976). Learning Style Inventory. Boston, MA: Hay Group, Hay Resources Direct.

Lewis, M. (1993). The lexical approach: The state of ELT and a way forward. Hove, UK: Language Teaching Publications.

Lewis, M. (2002). Implementing the lexical approach. Boston, MA: Thomson Heinle.

Μattheoudakis, M., & Alexiou, T. (2010). Identifying young learners’ learning styles in Greece. In M. C. Varela, F. J. F. Polo, L. G. García, & I. M. P. Martínez (Eds.), Current issues in English language teaching and learning: An international perspective (pp. 37-51). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Myers, L. B., & McCaulley, M. H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers Briggs Type Indicator. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Nikolov, M. (2009) (ed). Early Learning of Modern Foreign Languages: Processes and Outcomes. Bristol: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. New York, NY: Newbury House/ Harper & Row.

Oxford, R. L. (1999). “Style wars” as a source of anxiety in language classrooms. In D. J. Young (Ed.), Affect in foreign language and second language learning: A practical guide to creating a low-anxiety classroom atmosphere (pp. 216-237). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Oxford, R. L. (2003). Language learning styles and strategies: Concepts and relationships. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching (IRAL), 41, 271-277.

Oxford, R. L. (2011). Teaching and researching language learning strategies. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Oxford, R. L., & Ehrman, M. E. (1993). Second language research on individual differences. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 13, 188-205.

Palmberg, R. (2002). Catering for multiple intelligences in EFL coursebooks. Humanising Language Teaching (1). Retrieved from old.hltmag.co.uk/jan02/sart6.htm

Peacock, M. (2001). Match or mismatch? Learning styles and teaching styles in EFL. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11(1), 1-20.

Pinter, A. (2011). Children Learning Second Languages (Research and Practice in Applied Linguistics). New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Reid, J. M. (1987). The learning style preferences of ESL students. TESOL Quarterly, 21(1), 87–111.

Reid, J. M. (Ed.). (1995). Learning styles in the ESL/EFL classroom. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Rudd, R., Baker, M., & Hoover, T. (2000). Undergraduate agriculture student learning styles and critical thinking abilities: Is there a relationship? Journal of Agricultural Education, 41(3), 2-12.

Schmeck, R. R. (Ed.). (1988). Learning strategies and learning styles. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Šímová, K. (2011). Accommodating learning styles in EFL coursebooks for young

Learners (Unpublished dissertation). Masaryk University of Brno, Czech Republic.

Sternberg, R. J., Grigorenko, E. L., & Zhang, L. F. (2008). Styles of learning and thinking matter in instruction and assessment. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(6), 486–506.

Stirling, P. (1987). Power lines. NZ Listener, pp.13-15.

Vincent, J. (2001). The role of visually rich technology in facilitating children’s writing. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning,17(3), 242-250.

Wallace, W., & Oxford, R. (1992). Disparity in learning Styles and teaching styles in the ESL classroom: Does this Mean war? AMTESOL Journal, 1, 45-68.

Wesche, M. B. (1981). Language aptitude measures in streaming, matching students with methods, and diagnosis of learning problems. In K. C. Diller (Ed.), Individual differences and universals in language learning aptitude (pp. 119-154). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

| Visual | Auditory | Kinaesthetic |

| Unit 1 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 10 | 8 | 0 |

| Activity Book | 15 | 3 | 4 |

| Total: | 25 | 11 | 4 |

| | | | |

| Unit 2 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 8 | 8 | 3 |

| Activity Book | 13 | 2 | 5 |

| Total: | 21 | 10 | 8 |

| | | | |

| Unit 3 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| Activity Book | 12 | 2 | 1 |

| Total: | 20 | 7 | 4 |

| | | | |

| Unit 4 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 9 | 7 | 2 |

| Activity Book | 13 | 1 | 3 |

| Total: | 22 | 8 | 5 |

| | | | |

| Unit 5 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 9 | 6 | 4 |

| Activity Book | 12 | 3 | 2 |

| Total: | 21 | 9 | 6 |

| | | | |

| Unit 6 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| Activity Book | 12 | 3 | 2 |

| Total: | 22 | 10 | 5 |

| | | | |

| Unit 7 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 11 | 4 | 2 |

| Activity Book | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| Total: | 20 | 5 | 3 |

| | | | |

| Unit 8 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 12 | 4 | 2 |

| Activity Book | 12 | 0 | 4 |

| Total: | 24 | 4 | 6 |

| Total Sum: | 175 | 64 | 41 |

| Visual | Auditory | Kinaesthetic |

| Unit 1 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 7 | 7 | 3 |

| Activity Book | 13 | 1 | 3 |

| Total: | 20 | 8 | 6 |

| | | | |

| Unit 2 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| Activity Book | 15 | 1 | 1 |

| Total: | 25 | 8 | 4 |

| | | | |

| Unit 3 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 8 | 4 | 2 |

| Activity Book | 12 | 1 | 3 |

| Total: | 20 | 5 | 5 |

| | | | |

| Unit 4 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 12 | 6 | 1 |

| Activity Book | 14 | 3 | 2 |

| Total: | 26 | 9 | 3 |

| | | | |

| Unit 5 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 9 | 5 | 1 |

| Activity Book | 11 | 2 | 2 |

| Total: | 20 | 7 | 3 |

| | | | |

| Unit 6 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 10 | 5 | 1 |

| Activity Book | 11 | 1 | 2 |

| Total: | 21 | 6 | 3 |

| | | | |

| Unit 7 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 8 | 5 | 0 |

| Activity Book | 11 | 1 | 2 |

| Total: | 19 | 6 | 2 |

| | | | |

| Unit 8 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 8 | 6 | 1 |

| Activity Book | 12 | 0 | 2 |

| Total: | 20 | 6 | 3 |

| | | | |

| Unit 9 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 11 | 2 | 2 |

| Activity Book | 9 | 3 | 1 |

| Total: | 20 | 5 | 3 |

| | | | |

| Unit 10 | | | |

| Student’s Book | 11 | 4 | 0 |

| Activity Book | 9 | 1 | 4 |

| Total: | 20 | 5 | 4 |

| | | | |

| Total Sum: | 211 | 65 | 36 |

Please check the Methodology & Language for Kindergarten Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching English Through Multiple Intelligences course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|