The Courage to Be a Language Learner

Peter D. MacIntyre, Canada, Tammy Gregersen, US and Esther Abel, Canada

Peter D. MacIntyre is a professor of psychology at Cape Breton University in Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada. He is co-editor, with Tammy Gregersen and Sarah Mercer, of the forthcoming Positive Psychology in SLA (Multilingual Matters) and the 2015 title Motivational Dynamics in Language Learning (Multilingual Matters) with Zoltán Dörnyei and Alastair Henry. His main research area is in the psychology of second language learning and communication.

Tammy Gregersen is a professor of TESOL and teacher educator at the University of Northern Iowa (USA). She is the author, with Peter MacIntyre, of Capitalizing on Language Learner Individuality (Multilingual Matters) and has published extensively on individual differences, teacher education, language teaching methodology and nonverbal communication in language classrooms.

Esther Abel is a student at Cape Breton University. She is pursuing a Bachelor of Science Honours degree with a major in Psychology and a minor in Biology. Her interests include Positive Psychology, Statistics, and Social Psychology.

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Willingness to communicate: Is there a role for courage?

A lesson from Positive Psychology: The role of strengths

Courage in the classroom and beyond

Developing courage – specific classroom activities

Conclusion

References

This paper examines the potential role of courage in the language learning process. There is a considerable amount of research linking the characteristics of learners to their willingness to communicate in the target language, and research shows the value of authentic communication to language learning. Yet, even well motivated learners can be reluctant to undertake activities that might promote learning but also create high levels of anxiety (authentic interaction with native speakers, for example). To deal with learners’ hesitation, prior work on language anxiety has offered ways of reducing anxiety. An alternative approach, based on positive psychology, suggests that developing character strengths such as courage might produce a different type of learning outcome. Specific classroom activities aimed at developing courage are offered to demonstrate some ways in which teachers might engage with the goal of developing language learner courage.

Perhaps there are those who jump into language learning without hesitation, to whom the notion that language learning requires courage makes no sense at all. Let’s call them the lucky ones. For other learners, and we dare to suggest with no statistical evidence to support us that it is most adult learners, language can be a daunting, at times frustrating, and at least occasionally a frightening challenge. Although the second language acquisition (SLA) literature has discussed the importance of experiences such as language anxiety, lack of motivation, threats to identity, subtractive bilingualism, and many related processes, the recommended response to these issues often tends to be isolated to the identified issue. For example, dealing with language anxiety suggests there be strategies to reduce anxiety, such as using relaxation techniques or modifying the cognition that maintains anxiety (Gregersen & MacIntyre, 2014; Young, 1991).

Drawing upon the relatively recent literature in positive psychology, this article will propose a different tack. We will examine the courage to learn a language, using the literature on dynamic systems theory and positive psychology as two underlying but independent strands of thought. We will apply complex dynamic systems theory to understand how courage can support a willingness to communicate (WTC) in the target language. WTC helps to explain why some learners speak up and others remain quiet; we will relate WTC for first time to the concept of courage. The line of thinking underlying this paper comes from applying positive psychology to SLA (MacIntyre & Mercer, 2014). Although it has not been studied in the SLA area, the concept of courage has been identified as one of the core strengths of character and an important psychological construct that is gaining research momentum due to the emergence of positive psychology (Pury & Lopez, 2009). The final section of this paper provides a series of specific, practical activities that language teachers and learners might employ to develop their understandings of the courage to learn a new language.

Diane Larsen-Freeman (2007) has said “It is not that you learn something and then you use it; neither is it that you use something and then you learn it. Instead, it is in the using that you learn -- they are inseparable” (p. 783). Unfortunately, the idea that learning and communicating happen at different times serves to separate conceptualizing learning from the communication process. It allows classroom teachers to isolate what happens inside the classroom from what is happening outside, as if the real world is ‘out there’ and somehow not also ‘in here.’ This bifurcation of the learner and the learning might lead some teachers and curriculum designers to ignore the principle that languages are learned by people - whole, integrated persons. The whole person has hopes and dreams, experiences and fears, limitations and strengths that impact on the learning and communication process in significant ways. Larsen-Freeman (2015) has outlined her concerns that the language learning and teaching field has spent too much time with separate approaches to the learner versus the learning. “… I have been concerned for many years… about efforts to characterize the learning process removed from context, under the assumption that the process is universal, and that once understood, learner factors can simply be added, making some allowances for slight deviations from the general process for individual differences. This way of thinking is misguided...” (p. 18). Language teaching and learning work best when they consider the whole person, including how and why the person is learning the language and in what contexts.

In their model outlining the underpinnings of willingness to communicate (WTC), MacIntyre Clément, Dörnyei and Noels (1998) suggested that the primary goal of language teaching programs is to engender WTC. They positioned linguistic competence within a collection of interacting factors that make a person more or less willing to use the language they are learning. The WTC model proposes that the intergroup climate (i.e., relationships among language groups and linguistic communities) is one of the long-lasting, foundational elements of WTC, along with the personality of the learner. A variety of cognitive-affective processes that are developed over time, including attitudes, motivation, communicative competence, and self-confidence work together to support or restrict WTC. Interactions among the various processes underlying WTC reflect both approach and avoidance tendencies, that is, learners can experience conflicting emotions at the same time, reflecting a state of ambivalence (MacIntyre, 2007). Tensions within the learner, such as the dynamic interaction of language anxiety and motivation, are continuously being resolved in real time in ways that facilitate or inhibit communication, often with only subtle differences between them (MacIntyre, Burns, & Jessome, 2012).

One of the reasons why anxiety is prevalent in language classrooms is its connection to the fear of negative evaluation, both in terms of other people’s opinions of the learner and also in terms of academic evaluation and testing (see Horwitz, Horwitz, & Cope, 1986). There is a wide variety of ways in which people evaluate each other on a more-or-less continuous basis. Therefore the sources of anxiety are ever-present, numerous and complex – one person’s source of comfort can be another person’s source of anxiety. Even within the same person, a specific experience might engender anxiety at one time and not another. For example, a teacher’s error correction might be well received one day and not the next, depending on the learner’s mood, reaction of classmates, or subtle variations in the intonation of the teacher.

In a webinar for TESOL International, MacIntyre and Gregersen (2013) collected the many contributors to language classroom anxiety:

- fear of being laughed at, embarrassed, and making a fool of oneself

- errors in pronunciation

- a poor quality accent

- misunderstanding communication or using incorrect words

- cultural gaffes

- low self-esteem

- competitiveness

- fear of losing one’s sense of identity

- unrealistic learner beliefs

- instructors who intimidate their students with harsh, embarrassing error correction in front of other students

- methods of testing

- frequency and quality of contact with native speakers

- biased perceptions of proficiency

- personality traits such as shyness

- and many more

The list of items that may contribute to anxiety is quite long, as is the list of potential cognitive, academic, interpersonal/social, and personal consequences (see Horwitz, 2010; MacIntyre, 1999; Price, 1991). Research has shown negative effects of language anxiety on speaking, listening, reading and writing in the L2.

With so much at stake, it is important to ask what can be done to ameliorate the effects of language anxiety. Gregersen and MacIntyre (2014) recommend 15 activities that teachers and students can use to respond to anxiety. The majority of the techniques are designed to reduce anxiety through modification of its physical symptoms (e.g., through relaxation techniques), cognitive supports (e.g., by challenging anxiety-maintaining beliefs), and through developing positive interpersonal relationships (e.g., sharing experiences to reduce the sense of being alone in the experience). These strategies deal with the physical and emotional symptoms, as well as the cognitive deficits caused by anxiety arousal. In many ways this approach to anxiety reduction parallels the approach to anxiety taken by psychology in general – diagnose the specific condition at issue and deal directly with reducing its negative effects.

The emergence of positive psychology in SLA suggests that other approaches are possible (MacIntyre & Mercer, 2014). The focus of positive psychology is on what goes well in life, flourishing people, and engaging one’s character strengths (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Peterson, 2006). Strengths provide a different strategic starting point for dealing with anxiety and other issues with L2 learning and communication. We can pose the question this way: instead of focussing on reducing the deficiencies of the anxious learner, what if language teachers tried to develop learner strengths? In particular, we are proposing that a focus on courage might offer a novel way of examining what an anxious learner might do to facilitate positive language-related experiences.

“Courage has been praised by philosophers as a key virtue, perhaps even the key virtue” (Pury & Lopez, 2009). Interest from psychologists in the subject of character virtues and strengths has been limited, but has been gaining momentum. Over half of all peer-reviewed studies on courage have been published since 2001 (Pury & Lopez, 2009). Studies have been facilitated by the founding of positive psychology around the turn of the century (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) and by development of an inventory of strengths shortly thereafter (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Peterson & Park, 2009). This limited but growing source of research can be especially relevant to studies of character strengths in education, language, and communication.

Seligman (2002) considers strengths to be both acquirable and measureable; they can be taught, developed and refined over time. Strengths are valued ubiquitously across cultures as positive and respected attributes of respected people, and they are sought after. Their value is taken as self-evident in most cultures. Using strengths tends to inspire and elevate other people because strengths tend to be activated in win-win situations by persons who are respected. The diversity among people suggests that (1) patterns of strengths development differs from one individual to another, and (2) each person will have some strengths that are better developed than others.

According to Seligman (2002, p. 160), a person’s most prominent or “signature strengths” share a common set of characteristics:

- A sense of ownership and authenticity (“This is the real me”)

- A feeling of excitement while displaying it, particularly at first

- A rapid learning curve as the strength is first practiced

- Continuous learning of new ways to enact the strength

- A sense of yearning to find ways to use it

- A feeling of inevitability in using the strength (“Try and stop me”)

- Invigoration rather than exhaustion while using the strength

- The creation and pursuit of personal projects that revolve around it

- Joy, zest, enthusiasm, even ecstasy when using it

The above-listed characteristics of signature strengths make them an attractive concept for teachers and learners alike. Strengths connect well to concepts such as autonomy and competence that feature prominently in intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Exercising strengths brings a feeling of authenticity and greater energy to learning. Prior research has suggested that finding new ways to apply signature strengths creates an enduring positive effect on individuals (Mongrain & Anselmo-Matthews, 2012; Seligman et al., 2005).

Although research and theory in positive psychology has focussed on developing signature strengths, recent research suggests that the development of less prominent strengths provides greater consistency and balance among various strengths as well as unique psychological benefits (Young, Kashdan & Macatee, 2015). One criticism of Seligman’s approach to signature strengths has been the tendency to isolate strengths from each other, as if they were discrete parts of a machine (comparable to parts of a computer or automobile). This conceptual approach has led to the well-known exercise in the positive psychology literature that requires a person to isolate signature strengths and apply them in new situations, or what Biswas-Diener et al. (2011) called the “identify-and-use” approach. The rationale is that prevalent, easy-to-use, energizing character strengths are the best ones to be identified and employed. However, it is likely that the application of any one particular character strength in a specific context will affect at least some other strengths. For this reason, development of a strength such as courage likely will marshal resources associated with related strengths whether or not all of them are all signature strengths. Even when a person is focussed on identifying and applying one strength in particular, others will come along for the ride.

Courage is defined very broadly by a number of authors and the scope of the concept covers a wide territory, including physical, moral, and social forms of courageous behaviour. In acknowledging the lack of a standard definition for courage, Pury, Kowalski, and Spearman (2007) identify two types: (1) general courage that reflects actions that would be courageous for anyone and (2) personal courage that includes actions considered courageous only for the particular actor. Norton and Weiss (2009) adopt a behavioural approach, defining courage as actions that occur in spite of fear. Consistent with Norton and Weiss’ approach, the Woodard-Pury Courage Scale was developed based on self-reports of willingness to act in a variety of specific circumstances (Woodard, 2004; Woodard & Pury, 2007). For the purpose of the present paper, courage is defined as “acting in opposition to a variety of emotional forces” (Pury & Lopez, 2009). One implication of this definition is that there are emotional forces such as fear, worry, and anxiety that are working to inhibit action toward learning, placing courage squarely in opposition to language anxiety.

The theory and measurement of courage and related concepts has been greatly facilitated by the Values in Action (VIA) inventory of strengths and its web site that offers assessment of strengths for individuals (www.viacharacter.org/www/). The VIA Inventory uses a classification system that categorizes important positive trait-level characteristics into six overarching virtues and 24 character strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Courage is one of the six broad virtue categories, along with wisdom, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. Additionally, Park, Peterson, and Seligman (2004, p. 606) sub-divide courage into the areas of bravery (“Not shrinking from threat, challenge, difficulty, or pain; speaking up for what is right even if there is opposition; acting on convictions even if unpopular.”), perseverance (“Finishing what one starts; persisting in a course of action in spite of obstacles; taking pleasure in completing tasks.”), honesty (“Speaking the truth but more broadly presenting oneself in a genuine way; being without pretense; taking responsibility for one’s feelings and actions.”), and zest (“approaching life with excitement and energy; not doing things halfway or half-heartedly; living life as an adventure; feeling alive and activated.”).

Considered in the VIA taxonomy (see Table 1), courage is not a unitary trait but reflects the interaction of many experiences, both internal and external; it can be described in its specific parts or taken as a whole. It has been suggested that the VIA strengths interact as a complex dynamic system (Biswas-Diener, Kashdan, & Minhas, 2011). When courageous actions are taken, they are being inseparably influenced by, and are influencing, other psychological processes. Pury and Kowalski (2007) found the component traits of courage (persistence, bravery, and honesty) to be applicable to a variety of courageous actions, but in the same study found hope and kindness (which are not classified under courage by the VIA, but are classified under transcendence and humanity, respectively) also to be highly descriptive of courageous actions. In this way, we can see that courage can be at the centre of a network of strengths, interacting with other processes in context.

Table 1: Components of Courage within the VIA survey

| Courage – Emotional strengths that involve the exercise of will to accomplish goals in the face of opposition, external or internal |

- Bravery [valor]: Not shrinking from threat, challenge, difficulty, or pain; speaking up for what is right even if there is opposition; acting on convictions even if unpopular; includes physical bravery but is not limited to it

- Perseverance [persistence, industriousness]: Finishing what one starts; persisting in a course of action in spite of obstacles; “getting it out the door”; taking pleasure in completing tasks

- Honesty [authenticity, integrity]: Speaking the truth but more broadly presenting oneself in a genuine way and acting in a sincere way; being without pretense; taking responsibility for one's feelings and actions

- Zest [vitality, enthusiasm, vigor, energy]: Approaching life with excitement and energy; not doing things halfway or half-heartedly; living life as an adventure; feeling alive and activated

|

The pyramid model of WTC did not include the concept of character strengths in general or courage in particular. However, it is interesting to contemplate a potential role for strengths in generating L2 communication, learning, and WTC. Treating courage as a characteristic of a learner that can be developed and integrated in a network with her/his other characteristics has a number of potential implications for language teaching. Interventions developed based on a model of strengths rather than weaknesses produces a qualitatively different model of growth and education (MacIntyre, 2015). Extrapolating from a recent study of strengths in a working environment (Harzer & Ruch, 2013), we suggest that in an educational context, strengths such as courage likely will be present among the students at a sufficient level to allow them to be deliberately applied in their learning, provided that the educational context offers opportunities to apply the strength. Teachers can provide opportunities to authentically use the strength and facilitate its development. According to Harzer & Ruch (2013), in a sample of German adults, although it is not the most well developed strength, the single most applicable strength to both work and private life is honesty which is part of the courage cluster.

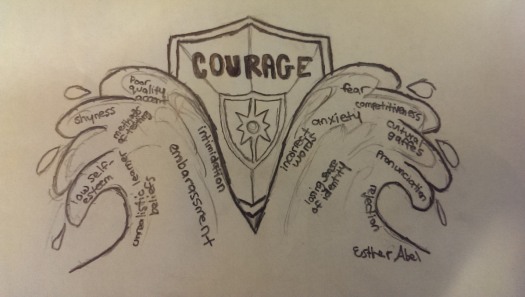

The goal underlying the present discussion of courage is to offer a novel approach to supporting learning and communication based on strengths development. It must be emphasized, however, that this approach is not in opposition to, or in place of, an approach to dealing with specific issues such as reducing language anxiety. Generally speaking, the two approaches are independent and complementary in nature. Using exercises to develop courage essentially sets aside anxiety (along with other negative emotions and prior experiences) as a part of the learning process. One might choose to deal with anxiety directly, reduce its intensity, alleviate its symptoms, and facilitate learning/ communicating. Anxiety reduction strategies can be successful. A strength-based approach to enhancing courage leaves anxiety to one side and encourages learners to acknowledge anxiety but take action in spite of it. In a metaphorical sense, courage provides a shield against waves of anxiety (see below).

Figure 1. Courage shielding the learner from anxiety

On one hand, a learner might say “I want to reduce anxiety and become more willing to communicate.” On the other hand, the learner might say “I feel anxiety but I still want to become more willing to communicate.” Luckily, learners almost always have two hands and can choose to use one or both of these approaches.

We wish to note that developing learner courage has not been the subject of prior research. However, it is possible to propose some ideas to get the ball rolling. The courage-related exercises in the following section are modelled after instructional activities proposed in Capitalizing on Language Learning Individuality: From Premise to Practice (Gregersen & MacIntyre, 2014). The literature review above supplies two key premises that can be summarized as follows:

- Language learning can be facilitated when learners show courage in overcoming obstacles in their learning.

- Courage can be taught by teachers and developed by learners through specific acttivities.

The section to follow draws on the definition of courage and its sub-component traits. Specific activities are suggested that address each of the aspects of the definition of courage as a character strength. Teachers can use their best judgement to adapt the specific ideas presented below to different circumstances, such as teaching younger versus older learners, and make modifications that use technology available to the local context, including using computer mediated forum (e.g., a wiki document or Twitter) to collect student reactions. It must be noted that the activities below have not been evaluated, they are offered as examples of what creative teachers might do in their classrooms. Reporting on the results of formal evaluation of these activities is strongly encouraged. There is a need for classroom-oriented research that considers the impact on learning of the dynamics of positive and negative affect, cognition, and character traits.

ACTIVITY 1: PUTTING ON MY BRAVE FACE

| Bravery [valor]: Not shrinking from challenge, difficulty; speaking up for what is right even if there is opposition; acting on convictions even if unpopular. |

Preface this activity by explaining to learners that in order to live with valor, there are pre-conditions: a philosophy of living on which to base convictions, a challenge to overcome, or an issue to speak up for.

- Provide a blank outline of a “coat of arms” that is divided into four quadrants and instruct learners to place their answers to each of the following questions in one of the areas:

- When you wake up in the morning and you think about your language learning, what is it that you would most like to accomplish?

- What guides your actions (particularly your impulsive ones) during class and when you are using the target language?

- What provides a feeling of contentment at the end of every class?

- What is the adjective that you would be most proud to have people apply to you that reflects how you approach language learning?

- Have learners sketch an emblem or motto about their shields that symbolizes the four answers above, reflecting important things in learning for them.

- With their metaphoric language shield in hand, tell learners that they will now practice their valor by overcoming a challenge or speaking up about their personal challenges in language learning.

- On another piece of paper, instruct learners to write a paragraph about a challenge in their language learning that they would like to overcome. Have learners attach their coat of arms with their motto, collect, shuffle and re-distribute them so that everyone has someone else’s but they do not know whose.

- Instruct learners to read the paragraph(s) and coat of arms they receive and write on the page some constructive feedback or encouragement to the learner who wrote it. When one person finishes, have him/her exchange papers with someone else who has finished providing feedback. Continue reading, writing and exchanging until everyone has read and provided encouragement to five classmates.

- De-brief this activity by asking learners to read the feedback they received. Remind them that bravery in learning means overcoming challenges. Ask each learner to choose his/her favorite feedback and to think about ways in which they can implement it.

ACTIVITY: DRAWING ON COMMUNITY TO PERSEVERE

| Perseverance [persistence, industriousness]: Finishing what one starts; persisting in a course of action in spite of obstacles; “getting it out the door”; taking pleasure in completing tasks. |

In preparation for this activity:

- Hang a long piece of paper horizontally across the wall and draw a “lifeline” along it.

- Hang several large pieces of paper or poster board with a line down the middle to create two columns in different places around the room. The exact number of posters will be defined in Step #4 below.

Preface this activity by explaining to learners that to persevere means more than just finishing something that was started (with or without obstacles), but also taking pleasure in its completion. Explain that sometimes perseverance needs a “spark”—an inspired moment which engages us to move in a renewed direction with energy and a heightened sense of fulfillment.

- Ask each learner to mark a date on the line of a time when they had persisted in a course of action in their language learning in spite of obstacles—to highlight an instance when they felt proud of an accomplishment that required perseverance.

- When everyone has had a chance to write their success story, ask learners to share and celebrate what they had written and what the obstacles were that they had to overcome to achieve it.

- Hand out five post-it notes to each learner and ask them to work silently to write one thing on each note that they would like to accomplish in their language learning journey. Have them post their individual ideas to a large surface.

- Upon completion of the notes, remind learners to remain silent and ask the whole class to organize the ideas by natural categories—that they define. Ask volunteers to write one category title on each large piece of paper that is hung around the room.

- Instruct learners to walk around the room, look at the different headings and sign their name in the first column on any of the sheets that represent goals which they have an interest in accomplishing. Next to their names (and still in the first column), tell learners to write down one obstacle they feel might impede their success.

- When all learners have had a chance to write down potential obstacles, ask learners to walk around to all the posters again and this time suggest a “spark” that might inspire a peer to move energetically in a renewed direction away from one of the obstacles.

- De-brief this activity on a high note by reading aloud the “sparks” that were written in the second column. Discuss the goals that learners have. Which goals had the greatest interest? What does that say about the group as a whole?

ACTIVITY 3: IMAGINING INTEGRITY

| Honesty [authenticity, integrity]: Speaking the truth but more broadly presenting oneself in a genuine way and acting in a sincere way; being without pretense; taking responsibility for one's feelings and actions. |

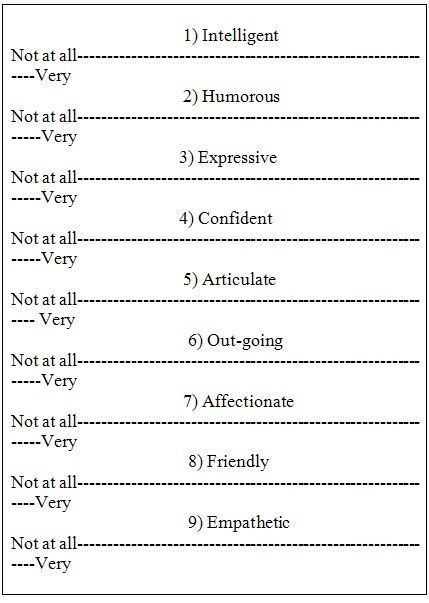

Preface this activity by explaining to learners that honesty means presenting oneself in a genuine way, without pretense, and taking responsibility for one’s feelings and actions. Explain that anxiety is often generated by learners’ awareness that they cannot present themselves as authentically in the target language as they do in their first language. To be genuine and without pretense, learners must first know who they authentically are.

- Either prepare the following information in a handout or instruct learners to copy it into their notebooks. Ask learners to place an “X” for their self-perception of each characteristic in their first language, and an “•” for their feelings about themselves in their target language.

- Ask learners to compare where their “Xs” and “•s” are on their continuums. Ask them whether they are surprised by how far apart or close together their “Xs” and “•s” are.

- Place learners in small groups and using the above categories, invite them to brainstorm a list of “visions”—including nonverbal behavior—that include projections of themselves as they present themselves honestly and sincerely in the target language. What do they look like? What do they say? In what circumstances might learners exercise their authenticity?

- Explain that the next step involves guided imagery, a strategy that capitalizes on students’ active imaginations and triggers visualization. Explain that the purpose of this activity is to bring to life learners’ visions of presenting their most honest, authentic selves in their target language. Instruct groups to collaboratively compose their own “Guided Imagery Scripts” using their brainstormed “visions for authenticity.” Here are a few guidelines (from: Gregersen & MacIntyre, 2014, p. 139):

- Begin your script with some basic instructions about getting comfortable, relaxing and looking inward.

- Include messages about being open to new input, suggestions, and ideas and to prepare to discard old patterns, behaviors and ideas.

- When groups begin to address their visions, try to incorporate all of the senses: What and how will learners see, hear, and feel as they experience the positive outcomes found in their authenticity? Keep the message positive and refrain from words, phrases, or images that might trigger a downbeat reaction.

- Give each group the opportunity to lead the class through their Guided Imagery Script, allowing learners to get comfortable on the floor, close their eyes, and visualize.

- De-brief this activity by asking learners whether envisioning their authenticity was helpful. Ask learners to discuss the importance they place on being “genuine”.

ACTIVITY 4: ZESTFUL ZEAL

| Zest [vitality, enthusiasm, vigor, energy]: Approaching life with excitement and energy; not doing things halfway or half-heartedly; living life as an adventure; feeling alive and activated. |

Preface this activity by explaining to learners that intensifying their courage to learn also includes approaching their target language with excitement and energy, throwing themselves into it with vigor. Tell them that by the game-like nature of this exercise, they will encounter their inner zeal!

- Tell each learner to use a small piece of paper to answer the question: “What words would be on your bumper sticker to let the world know the most exciting and invigorating adventure you have had in your language learning journey?” Let them know that it can be humorous and/or insightful—the idea is to have fun with this!

- Have learners create a large circle around the room. Ask each learner to take a turn going into the middle of the circle and reading aloud his/her bumper sticker. If anyone else in the room has felt a similar positive “vibe” or experienced that same adventure, have them run into the middle and do a group “high five”.

- Using the same idea of stirring up zest and zeal about language learning, invite learners to bring an artifact from home that best represents something symbolizing their activated excitement about their target language/culture or about their learning journey.

- Create the large circle again, but this time, go around it and allow each learner to share his/her artifact and explaining what it means to them. Provide a few moments to let learners respond with questions or encouragement.

- De-brief this activity by reiterating that approaching learning with zest is part of the courageous classroom you are intending to create. Encourage learners to continue helping others to live energetically!

It takes courage to sustain the language learning process and to express one’s self using the tongue of another person; there is a considerable amount of vulnerability inherent in the complexity of the learning process. Teachers and learners might use exercises such as those described here to consider ways in which to develop the courage to act in spite of anxiety. The notion of character strengths working with other learner attributes in a complex dynamic system offers an integrated, novel account of how the motivation to learn, anxieties, and willingness to communicate might be related to courage. The willingness of learners to expose themselves to the vulnerabilities of the learning process stems, in part, from a remarkable set of human strengths that positive psychology indicates can be both taught and learned.

Biswas-Diener, R., Kashdan, T.B., & Minhas, G. (2011) A dynamic approach to psychological strength development and intervention. Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(2), 106-118.

Gregersen, T. & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). Capitalizing on language learners’ individuality: From Premise to Practice. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Harzer, C., & Ruch, W. (2013). The application of signature character strengths and positive experiences at work. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(3), 965-983

Horwitz, E. K. (2010). Foreign and second language anxiety. Language Teaching, 43(2), 154-167.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2007) Reflecting on the cognitive–social debate in second language acquisition. Modern Language Journal, 91(1), 773–787.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2015). Ten ‘Lessons’ from Complex Dynamic Systems Theory: What is on Offer. In Z. Dörnyei, P.D. MacIntyre & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational Dynamics in Language Learning (pp. 11-19). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

MacIntyre, P. D., & Gregersen, T. (2013). Talking in order to learn: Insights and Practical Strategies on Learner Anxiety and Motivation. TESOL International, Live December 2013, archived at:

http://eventcenter.commpartners.com/se/Meetings/Playback.aspx?meeting.id=667479

MacIntyre, P. D., & Mercer, S. (2014). Introducing positive psychology to SLA. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 153-172.

MacIntyre, P. D. (2007). Willingness to communicate in the second language: Understanding the decision to speak as a volitional process. Modern Language Journal, 91(4), 564-576.

MacIntyre, P. D. (2015). Positive psychology in second language acquisition: Principles, practice and promise. Plenary talk at the 27th International Conference on Foreign / Second Language Acquisition, Szczyrk, Poland, May 2015.

MacIntyre, P. D. (1999). Language anxiety: A review of the literature for language teachers. In D. J. Young (Ed.), Affect in Foreign Language and Second Language Learning: A Practical Guide to Creating a Low-Anxiety Classroom Atmosphere (pp. 24-45). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

MacIntyre, P. D., Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. Modern Language Journal, 82(4), 545-562.

MacIntyre, P. D., Burns, C., & Jessome, A. (2011). Ambivalence about communicating in a second language: A qualitative study of French immersion students’ willingness to communicate. Modern Language Journal, 95(1), 81-96.

Mongrain, M., & Anselmo-Matthews, T. (2012). Positive psychology exercises work? A replication of Seligman. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 382 – 389.

Norton, P. J., & Wiess, B. J. (2009). The role of courage on behavioural approach in a fear-eliciting situation: A proof-of-concept pilot study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(2), 212-217.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603-619.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

Peterson, C. (2006). A primer in positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Peterson, C., & Park, N. (2009). Classifying and measuring strengths of character. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed.) (pp. 25-33). New York: Oxford University Press.

Price, M. L. (1991). The subjective experience of foreign language anxiety: Interviews with highly anxious students. In E. K. Horwitz & D. J. Young (Eds.), Language anxiety: From theory and research to classroom implications (pp. 101-108). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Pury, C. L. S., & Kowalski, R. M. (2007). Human strengths, courageous actions, and general and personal courage. Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(2), 120-128.

Pury, C. L. S., & Lopez, S. J. (2009). Courage. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (2nd ed). New York: Oxford University Press.

Pury, C. L. S., Kowalski, R. M., & Spearman, M. J. (2007). Distinctions between general and personal courage. Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(2), 99-114.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14.

Woodard, C., & Pury, C. L. S. (2007). The construct of courage: Categorization and measurement. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 59(2), 135-147.

Woodard, C. (2004). Hardiness and the concept of courage. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 56(3), 173-185.

Young, D. J. (1991). Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does the anxiety research suggest? Modern Language Journal, 75 (4), 426-39.

Young, K. C., Kashdan, T. B., & Macatee, R. (2015). Strength balance and implicit strength measurement: New considerations for research on strengths of character. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10 (1), 17-24.

Please check the Dealing with Difficult Learners course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

|