A Study on the Dynamic Peer Orientation of Foreign lLnguage Anxiety: A Classroom Perspective

Masoud Mahmoodzadeh, Iran

Masoud Mahmoodzadeh is a TEFL lecturer and EFL teacher at the Language Department of the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, Mashhad, Iran. He has published many papers in journals. His research interests include complexity theory/dynamic systems theory in SLA studies and psychology of language learning.

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Method

Participants

Procedure

Results and discussion

Pedagogical implications

Notes

References

This paper attempted to reflect on the dynamic peer-oriented nature of Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety (FLCA) in a small-scale classroom context. For this purpose, 32 Iranian language learners along with two EFL teachers participated in this study. To focus on the dynamic peer orientation of FLCA, temporal variations of the in-class anxiety among the students were examined. To do so, all the student participants were equipped with mini-stopwatches to record their FLCA on an ongoing basis over a timescale of one week. To measure the intensity and dynamics of the students’ in-class anxiety, the students were instructed to self-rate their anxiety intensity on a printed grid on the basis of a seven-point Likert scale at short regular intervals. In the meantime, to investigate the teachers’ awareness of the dynamics of their students’ in-class anxiety, the two teachers were similarly requested to rate the overall anxiety intensity of their students. After the analysis of data, the results signified the dynamic peer-orientation of FLCA and suggested that the dynamic nature of FLCA is not only attributed to intra-individual variations but also to inter-individual variations. The study also came up with some important pedagogical implications for language teachers as the results indicated the teachers’ considerable awareness of their students’ dynamic anxiety in the classroom.

There are many affective factors influencing language learning of foreign language learners in the classroom context. At the heart of these factors is a special emotional state called Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety (FLCA), which has long been recognized and researched. In fact, FLCA was the major focus of many scholars during the 1980s and the 1990s, resulting in several important studies on the role of FLCA on language learning process (e.g. Horwitz, Hortwitz, & Cope, 1986; Horwitz & Young, 1991; MacIntyre, 1999; MacIntyre& Gardner, 1989, 1991).

In the 1980s, however, Horwitz et al. (1986) were the first to introduce FLCA; they described FLCA as “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings and behaviors related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process” (p. 128). They argued FLCA is conceptually similar to three performance anxieties: communication apprehension, fear of negative evaluation, and test anxiety. To measure students’ anxiety levels, they introduced the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS), a 33-item Likert-type questionnaire based on a scale from one (“strongly disagree”) to five (“strongly agree”). However, research done in area of FLCA has yielded conflicting and scattered results concerning its effects on language learning (Young, 1991). In this sense, researchers have come up with debilitating (negative), facilitating (positive), and/or even no effects of FLCA on language learning (Dörnyei, 2005).

In research on FLCA, however, researchers have almost failed to take into account the dynamics of FLCA because the previous studies have mostly relied on product-oriented data gathered through retrospective methodological instruments such as self-report surreys, interviews and discussions , diaries, and third party observations (Gregersen et al., 2014; Horwitz, 2010). As rightly discussed by Gregersen et al. (2014), it is clear that the above investigative means are not process-oriented and thus cannot truly capture the dynamics of the moment-by-moment FLCA in the classroom context. To develop an understanding of how FLCA dynamically functions among the students in the classroom, it is thus necessary to consider the development of FLCA as a dynamic process. In other words, we may be able to explore patterns of FLCA changing dynamically over time through the use of tools and instruments developed for the study of dynamic systems1. In simple words, when it comes to the classroom context, the classroom itself is considered a system which obviously consists of many individuals that are, in fact, a group of students along with a teacher working together in the class. And the term dynamic here refers to the interrelationships of the students and the teacher who can dynamically influence each other in many different ways. It is hoped from reading this short description of dynamic system it becomes clear how people in the class are always emotionally interrelated to each other. With this in mind, the study particularly focuses on dynamic nature of anxiety, which is one of the important emotional states occasionally bothering foreign language learners in the classroom.

Even though having a quick scan through the literature implies the increasing awareness of the significance of dynamic systems in recent second language studies, it is unfortunate that there is only one study conducted recently by Gregersen, et al. (2014), which shows how FLCA changes dynamically in the real classroom context. Using an innovative method called the idiodynamic method, they developed a process-oriented approach to examining the dynamic nature of FLCA. With this in mind, it was thought worthwhile to devote another process-oriented study to focusing on the dynamics of FLCA. Therefore, the aim of this study is neither to focus on the effects of FLCA on language learning nor the sources of FLCA. Instead, the purpose is to explore the dynamic nature of FLCA from a classroom perspective. While the dynamics of FLCA is aimed for in this study, it is also believed that this type of in-class anxiety is importantly peer-oriented. That is, the fluctuation of FLCA should be considered and examined not only at an individual level but also at an inter-individual level. Therefore, this study tried to find the answer to the following questions:

Q1: What are the temporal patterns of the students’ in-class anxiety? Are the students dynamically influenced by their peers’ anxiety?

Q2: Are language teachers aware of their students’ in-class anxiety on an ongoing basis? If so, to what extent?

The study consisted of a two-fold group of participants: (1) thirty-three language learners (18 males and 15 females); (2) two EFL teachers. The student participants were older teenagers and young adults ranging in age from 15 to 21, who enrolled in a foreign language institute in Iran. The students were sitting in on two matched-gender EFL classrooms; 18 males in one classroom and 15 females in another classroom. It should be noted that the majority of language institutes in Iran do not offer coed education; therefore, it was decided not to focus on mixed-gender classrooms and examine the typical EFL learners in Iran. The proficiency level of the students was lower intermediate defined according to a locally-developed replacement test and an oral interview. The instructors were two regular EFL teachers; a 24-year old female with nearly one year of teaching experience and a 36-year old male with nearly 10 years of experience.

To observe the dynamic peer orientation of FLCA closely, the student participants were examined in the classrooms over a timescale of one week. This one-week time span met the aim of the study because this period was long enough to cover some materials in the course of lessons while keeping the participants sufficiently interested in the project. To focus on the temporal patterns of anxiety variations, all the student participants were equipped with handheld mini-stopwatches to record their perceived FLCA on an ongoing basis2. Using the split-time recording function of the stopwatch’s memory, however, the students in the two classrooms took turn using the stopwatches to indicate the temporal fluctuations of FLCA over three consecutive sessions. The students, in fact, were told to report the occurrence of their anxiety by simply pushing a button on the stopwatch as soon as it happens.

In addition, this study aimed to measure the intensity of the students’ in-class anxiety. To do so, the students were instructed to self-rate their level of anxiety on a printed grid containing 18 blank items (each item per interval) on the basis of a Likert scale of 1 (the lowest anxiety) to 7 (the highest anxiety) at regular intervals. On another level, attempts were also made to investigate the language teachers’ real-time awareness of their student’s anxiety in the classroom. Therefore, the two teachers were requested to rate the overall intensity of their students’ anxiety on the same easy to mark grid at the same time intervals. In doing so, in each classroom both the students and the teacher were prompted to report the level of FLCA respectively after a low pre-recorded beep sound heard from a laptop at 15-min regular intervals. It was believed that the report of ongoing FLCA among the participants at shorter and/or more intervals could seriously hinder the natural process of learning and teaching in the classroom and therefore could cause a lot of problems for both the teacher and the students.

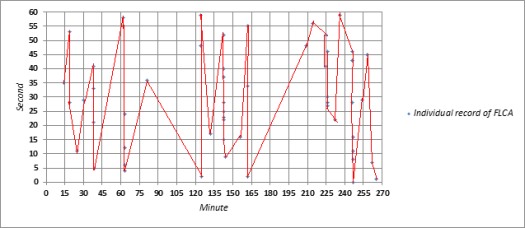

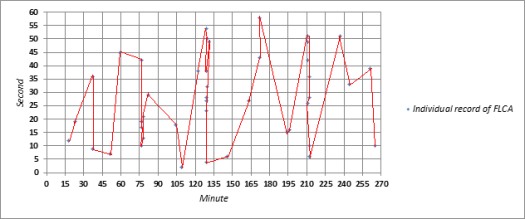

After keeping a record of the necessary data, the results indicated that there is indeed inter-individual variability in the students’ in-class anxiety intensity within the interval points over the timescale. In this regard, Figures 1 and 2 show the temporal variations of the individual records of the students’ in-class anxiety dispersed over a 270 min. timescale (three sessions). Overall, the results showed that the female students perceived more FLCA than the male ones because more females registered the occurrence of anxiety than males, whereas the females reported a higher intensity of anxiety over the timescale as well (see Figures 3 & 4). In addition, the females’ recordings of anxiety manifested more temporal fluctuations and naturally less stability as the females’ anxiety was subject to more temporal variations and changed more over time (see Figure 1).

Meanwhile, focusing on the emerging temporal patterns of the students’ FLCA interestingly makes it clear that there are some specific interval points in which both female and male students perceived relatively high degree of anxiety. Therefore, it can be implied that language learners can, indeed, influence one another in the classroom context.

Figure 1 Temporal scattegram of the female students’ FLCA

Figure 2 Temporal scattegram of the male students’ FLCA

In another sense, the findings of the study seem to emphasize what Dewaele, Petrides, and Furnham (2008) have explained as one of the underlying features of FLCA, namely the spreading flow of the learner’s anxiety. In this sense, Dewaele, et al. used the term “highly contagious” to describe the true nature of FLCA (ibid., p. 914). It is perhaps meaningful to say that the dynamic nature of FLCA is not only attributed to intra-individual variations but also to inter-individual variations. Therefore, when it comes to the emotional side of language learning, peer orientation of FLCA seems to play a key role and should become the focus of teachers’ attention because occasionally it can convey an air of negativity in the classroom in a short time. As a real-life example in the class, consider how an (over)anxious language learner can negatively influence other peers and change the emotional climate of the class as result. On the other hand, imagine how the decline in one language learner’s anxiety can positively affect other peers’ anxiety in the classroom.

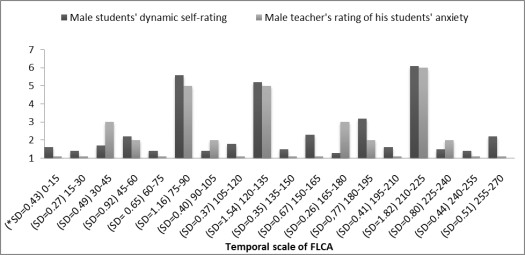

* Standard deviations of the students’ dynamic self-ratings

Figure 3 A comparison of overall dynamic mean of FLCA over a timescale of 270 min.

* Standard deviations of the students’ dynamic self-ratings

Figure 4 A comparison of overall dynamic mean of FLCA over a timescale of 270 min.

At this point, the question that naturally comes to mind is what roles language teachers can play here. To find the answer to this question, having a look at the dynamic self-ratings of the students and the teachers is necessary. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, both teachers were surprisingly aware of the overall intensity of their students’ anxiety on an ongoing basis to a relatively large extent. Interestingly enough, even the more inexperienced teacher was a bit more conscious of her students’ dynamic level of anxiety.

In short, the findings of the study suggest that language teachers consider the dynamic peer orientation influence of FLCA on all students. For this purpose, language teachers should pay a lot more attention to anxious or more importantly, overanxious learners in the class because they can unconsciously spread their anxiety throughout the classroom atmosphere, which can consequently impact on other peers’ learning. In a more practical sense, it is suggested that language teachers first try to make the class a less threatening place by being friendlier and less authoritative. Of course, as we have heard a relaxed teacher makes for a relaxed classroom; therefore, language teachers should also try to keep themselves relaxed most of the time in the class. While teaching in the class, they should also never ignore anxiety-stricken students and leave them alone after spotting them. Instead, they need to keep an eye on them and support them with continual positive and encouraging feedback to help them alleviate their anxiety intensity.

On the other hand, as the results of the study showed, the language teachers were interestingly aware of their students’ dynamic anxiety in the class. So it can be concluded that there are still plenty of rooms for the role of language teachers when it comes to helping to overcome FLCA and enhance learning; however, it is hoped that future large-scale research into the nature of FLCA will help increase our current understandings. To highlight more particularly the instructor’s practical role in the remediation of FLCA, there are two general guidelines proposed to language teachers below:

- Explore versus ignore. To make sure language learning is really happing in the class, try to be always aware of your students’ emotional states. And if you notice that a single student in your class is suffering anxiety in particular, try to get involved immediately to help him/her out. This kind of immediacy is necessary because the feeling of anxiety can grow and seriously influence other peers within a short time. To avoid this, first look for the cause of anxiety and then manage to find ways to overcome the anxious feeling on the spot. So good caring language teachers are never passive about the ever-changing emotional climate of the classroom; they constantly sense and observe the dynamic anxiety felt among individual students to facilitate language learning. Also good language teachers do not also expect too much from stressed-out learners when it comes to tackling FLCA in the class because it is, in fact, a matter of ‘fight’ or ‘flight’; only some students ‘fight’ against FLCA while many more simply prefer a ‘flight’. Language teachers should therefore dynamically check their students’ emotional states to make sure that English knowledge is imparted well in the class.

- Interact versus act. If you have concerns that students in your class are anxious, try to promote the teacher-student relationships in the class. This means that the act of teaching language materials is not basically enough to get the lessons across in the class. To make sure that language learning is occurring in the class, talk to the anxious students to become aware of what is emotionally happening and see how serious the problems are. Where necessary, even spend some time standing or sitting near them to help them feel like you are on their side, which can build safety for other peers as well. So always keep communication open in the class and create open channels for your stressed-out students to come to you for support and help when suffering or struggling with language anxiety. To understand and deal with FLCA, you, in fact, need to interact with your students instead of acting for them in the class. You cannot always understand how to help anxious students on your own, simply because you are familiar with the ups and downs of learning English in a way or because you used to learn English as a foreign language not long time ago. To tackle the problematic situations caused by FLCA, it is perhaps a good idea to work on promoting your student-student relationships in the class, too. One thing to decrease FLCA is to pair students for activities rather than allowing them to choose their pairs. It is thought that pairing (over)anxious students with nearly non-anxious students (student helpers) helps to prevent the (over)anxious from being left out, which can empower them to resist the negative peer orientation influence of FLCA at the same time. In simple words, language learning does not happen if every man is for himself in the class when it comes to the emotional factors of language learning such as language anxiety.

1 It is noted that the major property of Dynamic System (DS) is basically its dynamic change over time (de Bot, Lowie, and Verspoor, 2007). For a full understanding of the applications of Dynamic System Theory (DST) in the field of applied linguistics, interested readers are advised to study de Bot (2008), de Bot, Lowie, Verspoor (2005), de Bot, Lowie, and Verspoor (2007), and van Geert (2008). In this paper, the author avoids using the DST nomenclature for the sake of non-specialist readers.

2 Of course prior to the study, the use of the tools was piloted with a similar group of students.

de Bot, K. (2008). Second language acquisition as a dynamic process. The Modern Language Journal, 92(2), 166–178.

de Bot, K., Lowie, W. & Verspoor, M. (2005). Dynamic systems theory and applied linguistics: The ultimate “so what”? International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 15 (1), 116–118.

de Bot, K., Lowie, W., & Verspoor, M. (2007). A dynamic systems theory approach to second language acquisition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 10(1), 7-21.

Dewaele, J. M., Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2008). The effects of trait emotional intelligence and sociobiographical variables on communicative anxiety and foreign language anxiety among adult multilinguals: A review and empirical investigation. Language Learning, 58(4) 911-960.

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gregersen, T., MacIntyre, P. D., & Meza, M. D. (2014). The motion of emotion: Idiodynamic case studies of learners' foreign language anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 98(2), 574-588.

Horwitz, E. K. (2010). Research timeline: Foreign and second language anxiety. Language Teaching, 43(2), 154-167.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132.

Horwitz, E. K., & Young, D. J. (1991). Language anxiety: From theory and research to classroom implications. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

MacIntyre, P. D. (1999). Language anxiety: A review of the research for language teachers. In D. J. Young (Ed.), Affect in foreign language and second language learning: A practical guide to creating a low-anxiety classroom atmosphere (pp. 24-45). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

MacIntyre, P. D., & Gardner, R. C. (1989). Anxiety and second-language learning: Toward a theoretical clarification. Language learning, 39(2), 251-275.

Maclntyre, P. D., & Gardner, R. C. (1991). Methods and results in the study of anxiety in language learning: A review of the literature. Language Learning, 41(1), 85-117.

van Geert (2008). The dynamic systems approach in the study of L1 and L2 acquisition: An introduction. The Modern Language Journal, 92 (2), 179-199.

Young, D. J. (1991). Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does the language anxiety research suggest? Modern Language Journal, 75, 425-439.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

|