Dear HLT Readers,

Welcome to the August issue of HLT. First some Pilgrims news. We are all enjoying the inspirational and fun atmosphere of the courses taking place at the Hilltop at the University of Kent in Canterbury. We hope you will join us one day.

To come to Pilgrims, apart from the Erasmus+ grants you can apply for the Bonnie Tsai Scholarship, the details of which you will find in the Course Outline section.

Also, in the months to come, there will be many opportunities for us to meet such as the ALL IN: Educate and Include Conference in Italy, at the IATEFL Conference in Poland, and many others. Please look up Pilgrims trainers or staff if you attend any of these events. We will be very happy to chat to you, brainstorm and make plans.

The C for Creativity contribution this issue is Does the C Group Have a Future?, byAlan Maley, who with this text steps down from his involvement in the group. Happy 80th birthday and happy retirement Alan! You truly deserve it and thank you for your massive involvement and impact you have made on EFL worldwide.

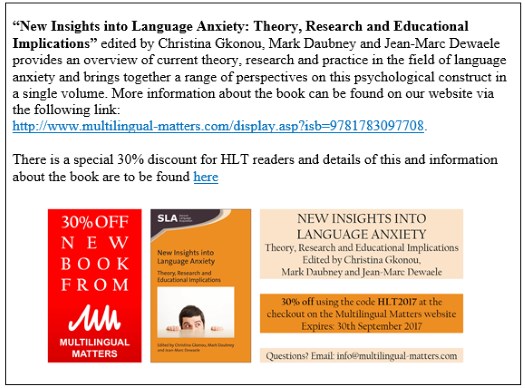

This issue also contains a lot of information from the publishing market in Publications and Book Preview sections. In this editorial you can also find information about a fascinating new book and a special offer for HLT readers.

The main body of the issue is host edited by Jane Spiro whom I would like to thank for harvesting so many interesting contributions and for her hard editorial work. I am immensely impressed by Jane’s expertise and dedication. Working with you has been a real pleasure

Happy reading

Hania Kryszewska

HLT editor

hania.kryszewska@pilgrims.co.uk

Jane Spiro is reader/principal lecturer in education and TESOL at Oxford Brookes University. She runs programmes in ELT materials writing and methodologies, and has run teacher development programmes worldwide, including Poland, Mexico, Sri Lanka, Kenya, Japan and China. Her book ‘Changing Methodologies in TESOL’ with Edinburgh University Press was self-reviewed in HLT and her next book with Palgrave Macmillan is in press for publication in December 2017, ‘Cultural and Linguistic Innovation in Schools: the Languages Challenge’. She is a founding member and co-convenor of the C-group.

Introduction

Welcome to the special issue of HLT, which brings together language teaching and the creative arts: drama, sculpture, visual arts, dance, poetry and story. The special issue sprang out of an idea which began in 2015, to bring together ELT and modern language teachers and to find out what they can learn by working with artists of word, movement and image for a day. The event took place in May 2015 at Oxford Brookes University and many of the contributions in this special issue are inspired by what took place. Our contributors write from Brazil, Malta, Czech Republic, Kazakhstan, France, Germany, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, New Zealand and the UK. Such a breadth of response must reassure teachers inspired by the join between language and creative arts, that they are not alone. As one teacher unravels the language of a vase in a Kazakh museum, in Italy another teacher is using Kandinsky as a springboard for a class project and another public art in the Czech Republic.

Language and three dimensions

Ways of looking at objects, and objects as a pathway to language is one theme in this special issue. Tamar McLellan in the lesson plan section writes as an art educator with a mindfulness of the join between thinking in images and thinking in words. She takes us through the questions that can be asked about everyday objects, encouraging students of art to engage with the objects around them in multiple and deeper ways. By looking at objects as an art educator, Tamar helps us also to see what we can do with objects as language educators. Martina Šindelářová Skupeňová introduces us to language tasks which make sculptures their starting point, from classical statues to post-modern sculptural art. Her lesson encourages learners to ask questions about public art, to think about the process of commissioning, and consider its connection with history, ideology and politics. At the Brookes symposium we looked at the hanging sculpture Resounding with Rachel Payne, art educator, asking questions about colour, light, texture, weight, structure and symbolism. Alan Maley’s poem about the sculpture responds to these questions, leaping out from what was seen to what was felt and imagined. Zaure Kulchikenova in the poetry section tells the story of discovering poetry on the sides of a historic jug in her local museum. Objects can be integrated playfully into learning, as Sabrina Bechler shows us in her travel blog article, where Sally the Australian kangaroo puppet ‘travels’ round the world, photographed (by her) in exciting new settings. Children could imagine themselves there, talking to their puppet friend and learning about different parts of the world. To forge yet further the join between objects and language, I invite you to read the short article by John Daniel. He writes about looking at a pebble on the beach, and then a pebble on the mantelpiece, realizing that things ‘found’ can become art objects if placed into a different setting. In the poetry section are four ‘found’ poems which came from his workshop, as the workshop participants searched the university building and found poems in a flipchart, notices in the corridor and on their iphone (by Charlie Hadfield, Jill Hadfield, Sandra Santarelli and Alan Pulverness).

Language and art

We see the impact the language-art join can have on learners, in the article of Letizia Cinganotto. She analyses art projects across the curriculum carried out in Italian schools, and gives us rich examples of their benefits to learners “in terms of students’ creativity, motivation, enthusiasm, transversal competences and learning outcomes.” Malu Sciamarelli’s lesson starts with learner drawings, and to be congruent with this herself, shares in the poetry section her own drawing of a tree and the poem that sprang from it.

Language and dance

Amongst the several ‘intelligences’ we develop when combining language with the creative arts, is the physical/kinaesthetic intelligence of movement. Jane Spiro describes in the lesson plan section, the session given by dance educator Jean Clarke, where we developed a vocabulary of movement, building up from words/individual movements, to whole linguistic and dance sequences. She argues that there are few examples in ELT as a profession, of learning activities which bring dance into the frame, and that dance is the ‘missing link’ in the join between language and the creative arts.

Building emotional intelligence: poem, story, drama

Many of the contributions in this issue show how the language arts, poetry, story and drama, build not only language but emotional intelligence and empathy. Several of the contributors have been explicit that they see this as integral to their role as language teachers. Margaret Issitt shares with us the voices of students with special needs, whose words in conversation with her emerged as a kind of pure and natural poetry. Nergis Curtis elicits from her learner a heartfelt poem of the experience of being an asylum-seeker in the UK. We can find these examples in the section on Student Voices, along with the poem of a young Saudi Arabian learner recounted by Norah AlJahyah. Inna Batorina-Bougoin shows us how two students resolved a conflict that made it difficult for them to work together, by acting out a drama sketch between a quarrelling husband and wife. Angeliki Voreopoulou’s lesson, like that of Inna’s, began with conflict between two learners, and shows how story can be used to turn conflict into a source of learning. Hugo Dart, Adriana Nogueira and Accioly Nóbrega use a different approach to the building of empathy through poetry. They start with the written words of two iconic First World War poets, Rupert Brookes and Wilfred Owen and show us how close linguistic reading can ‘open doors to dealing with otherness in a more empathetic manner’. Their article also suggests that surface levels of analysis can lead to ever deeper meanings – from pronoun or modality to appreciation of ‘the pity of war’.

Language and kinds of writing

Alan Maley’s major article gives us a rare insight into the processes of a multi-tasker whose writing includes teaching resources, stories, poems, novels and textbooks. Even so prolific a writer admits to the blocks and pitfalls of being human, and shares with us ways through the myths that hold us back.

Lest we take ourselves too seriously, I commend you to Michael Swan’s ‘spoofs’ in the Joke section. By reading his joke abstracts for an Applied Linguistics conference, his ‘five best reads’, or his impenetrable corpus analysis, we might recognize our most pompous and self-defeating selves. These are great examples of what we try not to be, but sometimes look as if we are!

A creative smorgasbord

Daniel Xerri’s article reminds us of the core theme that connects all the contributions to this special issue: creativity. He reminds us of how contentious this word continues to be, in spite of significant recent research and publications. His article is a helpful ‘state of the art’ snapshot of where we stand in 2017 with regard to creativity myths, polarities and patterns. He starts with a quotation from Ken Robinson (2012): “We’re all born with deep natural capacities for creativity and systems of mass education tend to suppress them.” The contributors to this issue have defied this tendency, and shown that these capacities are indeed valued and empowered by good teachers. We have shown that classrooms which foster creativity also foster well-being, compassion, criticality and self-esteem.

As a way of both opening and closing this issue, I would like to offer you a ‘smorgasbord’ of quotations about creativity to think about. These quotations were chosen by three participants at the Oxford Brookes Creativity symposium, Netta Gorman, Eiko Kato and Alicia Otero, and placed around the walls of the workshop rooms. They are here placed around the virtual walls of this special issue as gentle reminders of others who have travelled the same journey.

- If you want creative workers, give them enough time to play. (John Cleese)

- Anxiety is the handmaiden of creativity. (T.S. Eliot)

- Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once the child grows up. (Pablo Picasso)

- Odd how the creative power at once brings the whole universe to order. (Virginia Woolf)

- Creativity is that marvellous capacity to grasp mutually distinct realities and draw a spark from their juxtaposition. (Max Ernst)

- Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go. (T. S. Eliot)

- Others have seen what is and asked why. I have seen what could be and asked why not. (Pablo Picasso)

- We have to continually be jumping off cliffs and developing our wings on the way down. (Kurt Vonnegut)

- Imagination is everything. It is the preview of life’s coming attractions. (Albert Einstein)

- The unlike is joined together, and from differences results the most beautiful harmony. (Heroclitus)

- If you hear a voice within you say You cannot paint, then by all means paint, and that voice will be silenced. (Van Gogh)

- Creativity is intelligence having fun (Albert Einstein)

- Don’t think. Thinking is the enemy of creativity. It’s self-conscious, and anything self-conscious is lousy. You can’t try to do things. You simply must do things. (Ray Bradbury).

- You imagine what you desire, you will what you imagine, and at last, you create what you will. (George Bernard Shaw).

- Curiosity about life in all of its aspects, I think, is still the secret of great creative people. (Leo Burnett)

- There is no doubt that creativity is the most important human resource of all. Without creativity, there would be no progress, and we would be forever repeating the same patterns. (Edward de Bono).

Enjoy the August issue of HLT,

Jane Spiro

Jane Spiro

|