Language for Art in a CLIL Curriculum: Some Case Examples from Italian School Projects

Letizia Cinganotto, Italy

Letizia Cinganotto holds a PhD in linguistics and is a researcher at INDIRE, the Italian Research Institute for Innovation, Documentation and Educational Research. She is a former teacher of English at upper secondary school level, trainer and author of digital content. She worked at the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research, Directorate General for Schooling, dealing with issues relating to foreign languages and CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning). In that position she coordinated projects involving school networks all over Italy. She took part in a wide range of Working Groups and Steering Committees at national and international level. In fact she also took part in different meetings with the European Commission. She has presented papers at national and international conferences and published articles in peer-reviewed journals. Her main research areas involve e-Learning, blended learning, CLIL, TELL, CALL, EFL, MALL, teacher training.

E-mail: l.cinganotto@indire.it

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Background

Examples: Techno-CLIL

Examples: E-CLIL

Conclusions

References

The paper will be focused on the link between languages and Art in a CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) curriculum, analyzing some case examples of projects carried out in Italian schools. In fact CLIL has become compulsory in the Italian upper secondary school curricula and a high number of schools opted for Art as the subject content delivered in the foreign language using CLIL methodology. The description of some lesson plans and examples of products produced by the students also with the use of learning technologies will be provided to show the added value language for art can bring to CLIL in terms of students’ creativity, motivation, enthusiasm, transversal competences and learning outcomes.

CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) (Marsh, 1994) is an innovative methodology focusing on the learning of language whilst simultaneously teaching content from a subject area such as humanistic or scientific area (Coyle et al., 2010). Therefore CLIL means using a foreign or second language as a medium of instruction and learning for primary, secondary and/or vocational-level subjects such as maths, science, art or business (Mehisto et al., 2008). According to Mehisto et al., some key features are crucial to create an effective, CLIL oriented learning environment, such as:

- grade-appropriate levels of academic achievement in subjects taught through the CLIL language;

- grade-appropriate functional proficiency in listening, speaking, reading and writing in the CLIL language;

- age-appropriate levels of first language competence in listening, speaking, reading and writing;

- an understanding and appreciation of the cultures associated with the CLIL language and the student’s first language;

- the cognitive and social skills and habits required for success in an ever-changing world (Mehisto et al. 2008:12).

It is easy to understand that CLIL methodology is flexible and adjustable to the learners’ needs, levels of language competence and levels of academic achievement.

One of the target subjects for CLIL may be art, which can help develop the students’ aesthetic sense, guiding them to appreciate fine art masterpieces and to enhance their creativity. Describing, analyzing, reproducing a work of art using a foreign or second language may activate the learners’ higher order thinking skills, improving both language competence and artistic sensitiveness.

Moreover as Geddes and White (1978) stated, teachers should aim for authenticity in order to bring the real world into the classroom. Art works can help teachers and learners discuss, compare ideas, feelings and emotions with strong links to the real world.

As for language proficiency, an interesting issue to reflect on is whether students should be competent enough to discuss the work of fine art or whether they should wait until their level of competence is so good as to allow them to express feelings, emotions and aesthetic concepts in an appropriate way. According to Grundy et al. (2011:10) “one of the most significant methodological issues in language teaching is the issue whether we learn language in order to use it or whether we learn a language through using it.” This recalls what Coyle (Coyle et al., 2010) defines as the language triptych: language of learning, language for learning, language through learning, exploiting all the different opportunities the language can provide to enhance the learning process.

As far as the language dimension is concerned, seven principles for language practice in CLIL can be identified (Ball et al., 2015):

- “Mediate” language between the learner and new knowledge

- Develop subject language awareness

- Plan with language in mind

- Carry out a curriculum language audit

- Make general academic language explicit

- Create initial talk time

- Sequence activities from “private” through to “public”.

Therefore the role of the teacher is essential as “language mediators in order to ‘build bridges’ between the learners and the new subject knowledge” (Ball et al., 2015: 71).

CLIL methodology seems to be aimed at building bridges: between language and content; between the learner and the new subject knowledge; between the language teacher and the subject teacher, etc. Art and imagery can help build bridges among verbal language (general academic language/subject specific language), iconic language, emotional language, subject content. More and more universities, colleges and training institutions are offering courses for teachers and trainers on CLIL in art: an example is the course delivered at St Giles International in London, which has been included on the School Education Gateway portal.

As Genesee and Hamayan point out, “more and more parents in communities around the world want their children not just to acquire minimal proficiency in an additional language (often English), but to reach high levels of bilingual proficiency and they are looking for innovative educational approaches to achieve this” (Genesee and Hamayan, 2016:3). Among the different features, the CLIL approach is action-oriented, task-based and student-centered. It aims at combining language practice and specific content delivery and fosters foreign language and intercultural competence acquisition.

CLIL methodology takes advantage of a wide range of teaching strategies, which, according to Hattie (2009), can have a huge impact on learning; in particular, Hattie’s top ten teaching strategies are the following:

- Direct Instruction

- Note Taking & Other Study Skills

- Spaced Practice

- Feedback

- Teaching Metacognitive Skills

- Teaching Problem Solving Skills

- Reciprocal Teaching

- Mastery Learning

- Concept Mapping

- Worked Examples.

These teaching strategies can be effective in terms of students’ learning outcomes and teachers’ innovative practices and can all be included in a CLIL approach. In fact, CLIL is considered by the European Commission as a driver to innovation and as an effective methodology, which can contribute to improve the quality of education all over the member states. The recent report from Eurydice (2017) Key data on teaching languages at school in Europe highlights CLIL provision all over Europe, pointing out that it has expanded considerably in all member states, but only a few of them have adopted it as a national education policy, introducing it at a certain level of education and Italy is among them.

In fact in Italy CLIL has been mandatory in the final year of upper secondary schools since the Reform Law 53/2003, in particular according to DPR 88/89 dated 2010 (Cinganotto, 2016). The recent “Good School” (Law 107/2015) encourages CLIL application to primary and lower secondary schools, considering it successful at enhancing foreign language learning and subject content acquisition at the same time. Upper secondary schools are supposed to deliver a subject in a foreign language (mainly English) in the fifth year. While “licei” (“grammar schools”) can choose among different subjects to deliver in CLIL, in technical schools the CLIL subject must be chosen from the specialist areas. A wide range of “licei” have opted for Art as the CLIL subject in recent years: figures have rapidly increased, as the latest monitoring reports carried out by the Italian Ministry of Education show (Fig. 1).

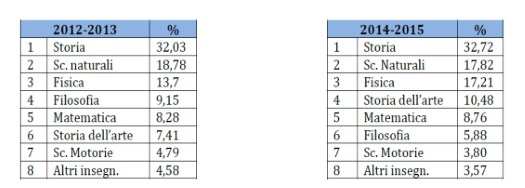

Fig. 1 – CLIL subjects in “licei linguistici” in school year 2012-13 and 2014-15

In school year 2012-13 Art and History of Art were in sixth position (7.41%) as the CLIL subject in “licei linguistici” (upper secondary schools with a particular vocation to languages); in school year 2014-15, figures were even higher (10,48%), replacing philosophy in fourth position.

The other subjects were: history; natural sciences; physics; math; P.E.; other subjects.

Another monitoring report has been carried out by the author of this paper and INDIRE research team on behalf of the Ministry of Education, with the aim to collect and analyze the outcomes of the CLIL projects funded by the DG for Schooling of the Ministry, according to DM 435/2015.

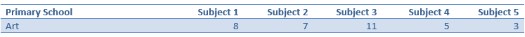

A wide range of projects realized by the schools chose Art, for their CLIL project, especially at primary level (Fig. 2), where Art was chosen by 8 schools out of 143 as the first subject and by 11 schools as the third option.

Fig. 2 – Art as CLIL subject for the E-CLIL projects in the primary schools

The following paragraphs mention some examples of CLIL projects in Art with the use of learning technologies, taking into account some different training initiatives and learning pathways.

In January and February 2017 the author of this paper co-moderated, together with a very skillful expert, Daniela Cuccurullo, a free online training session, named “Techno-CLIL” (Cinganotto, 2016), within EVO (Electronic Village Online), Tesol International, registering 5000 participants from all over the world, mainly Italy, engaged in learning experiences on CLIL and technologies.

In fact, as also recommended by the European Commission (2014), there is a strong link between CLIL and CALL (Computer Assisted Language Learning), so the use of learning technologies should be fostered to enhance language learning and CLIL.

Learning technologies can actually represent an added value in a language or CLIL learning environment (Stanley, 2013). With the term “learning technologies” we generally refer not only to computers and related hardware, but also to programs and tools, i.e the software (Hockly, 2016). Moreover it is essential to take into account how teachers and learners, the so-called “liveware” (Hockly, Clandfield, 2010) interact with these technologies and each other and their impact on language learning.

During “Techno-CLIL” the participants were asked to work on CLIL and technologies choosing the subject they preferred, considering their personal and professional background.

A large number of teachers opted for art, as their CLIL subject for Techno-CLIL tasks.

Below is an example of a lesson plan where the history of the Great Wall of China is mentioned: it is addressed to lower secondary school students with an intermediate level of language competence (A2/B1). The historical, geographical and artistic perspectives are interwoven throughout the lesson plan, which is a good example of an interdisciplinary learning unit.

| Topic | THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA |

| Subject/s | History/Geography/Art |

| Target | The lesson was meant for middle school students but it can be applied to higher level students just changing the tasks required. |

| Target competence level (A1,A2,B1,B2, C1, C2) | A2/B1 |

| Number of hours (approx) | 2 hours and a half |

| Objectives | Language: Describing a historical monument, using past tenses and the passive form.

Content: History of the Great Wall

Technology: Use of the internet for the webquest. |

| Outcomes (links, resources etc.) | www.historyforkids.org

www.britishmuseum.org

library.thinkquest.org/20443/greatwall.html

www.activityvillage.co.uk/introduction_to_china.pdf

www.china.mrdonn.org/greatwall

www.chinahighlights.com/greatwall/fact

library.thinkquest.org/20443/greatwall.html

www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/greatwall

www.activityvillage.co.uk/the_great_wall_of_china.htm | |

| Assessment | Students in groups of 5 will be evaluated by the rest of the class, after their performance. Self-evaluation within the class. |

| Webtools and/or devices used | Google; Wikipedia; PPP presentations. |

| FOCUS ON THE LANGUAGE | |

| Subject-specific language of the lesson | The students will learn how to use the following expressions:

It is built/constructed; It is made of; It is situated in;

Vocabulary connected to Architecture, History and Geography. |

| Technology-specific language of the lesson | Google search; Wikipedia. |

| General academic language of the lesson | Being able to describe a monument pretending to be a tourist guide. |

Table 1: Example of CLIL lesson plan in Art

The following paragraph includes the comments and the description of the lesson plan by the author (Luciana Ingrosso), with reference to the aims of this activity in the framework of a CLIL approach.

“I have never tried this activity with a class, but its structure and content can be used for any type of lesson.

According to the CLIL methodology, the actors of the lesson are students throughout the entire activity, while the teacher is just an observer and a guide, showing them the path to follow.

Content is not given by the teacher, but found out by students through their web-quests. This means that their learning is not taught, but supported by technology and their own doing. At the same time, the lesson plan is aimed at guiding students when surfing the net in order to teach them how to select information and distinguish ‘good’ websites from ‘bad’ ones.

Students will also learn to work in teams and to share duties and responsibility, because all the activities proposed are based on collaboration from the very beginning and will end with the production of the team’s common document, to be presented to the rest of the class.

Evaluation within the class after their performance is peer-centered, to help critical awareness. Evaluation won't be just a mark, but the result of a positive discussion on strengths and weaknesses and suggestions on how to improve their mutual work.

Thanks to this plan, students will learn to give a speech, as if they were tourist guides, while the others will learn how to intervene with questions and personal comments, thus making the learning of a subject more practical and real”.

Some interesting aspects of the lesson plan are worth commenting on: the authentic task, making the students the real protagonists of their learning paths, acting as tourist guides; the peer-assessment, developing critical thinking skills and the attitude towards self-evaluation and peer-evaluation; the use of ICT for CLIL activities, in particular the web-quest, which is an effective way to promote a critical use of the internet (Cinganotto, Cuccurullo, 2015).

Web-quest for CLIL, named CLILQuest (Fontecha, 2010), refers to a learner-centered activity based on inquiry-oriented learning tasks, entailing searching for resources on the web, in a CLIL environment.

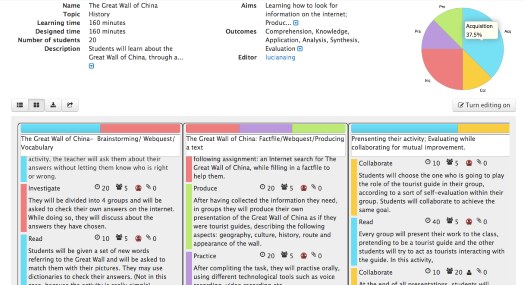

Another example of learning technologies for CLIL is the Learning Designer, a webapp which can be used for lesson planning and allows the teacher to plan in detail every single step of the lesson, specifying the kind of activities to carry out with the students (investigate, produce, read, collaborate etc.), also defining the time to devote to those activities. The visual rendering is particularly impressive (Fig. 3), as it allows the teacher to visualize the impact of the lesson in terms of types of activities and time devoted to them, so that it is easy to change something for the next lesson plan, if relevant. In particular, the graph shows how the students are actively engaged in the learning path, realizing their own presentation of the Great Wall, after collecting information and acting as tourist guides. (Luciana Ingrosso’s Learning Designer, shown in Fig. 3, can be consulted at the following link: https://v.gd/aSXDF2).

Fig. 3 – Example of Learning Designer in CLIL for Art

Another example of a CLIL project for art has been taken from the projects funded by the Ministry as specified by DM 435/2015. School networks were asked to plan and implement CLIL modules with the use of technologies (“E-CLIL”), according to some measures and projects promoted by the DG for Schooling in recent years (Langé, Cinganotto, 2014).

One of the school networks decided to create an e-book (Fig. 4) about the city of Lucca, in Tuscany, presenting some buildings and monuments in English through visual inputs, videos, texts and final quizzes to check learning. It is a digital content planned and produced to highlight the city of Lucca by exploring some of the most important places and describing them in English. It is a very good use of learning technologies for CLIL, allowing students to know their city better and discover artistic features they probably do not know, using the foreign language to express artistic and historic content. It is also a valid way to get them aware of their national and European citizenship.

(The ebook has been developed within the framework of the “CLIL4ALL” E-CLIL project which can be consulted here: http://www.piaggia.it/eclil. In particular the ebook “Unusual Sights of Lucca” by L. Nicolai is available here: www.epubeditor.it/ebook/?static=44008).

Fig. 4 – E-book about the city of Lucca

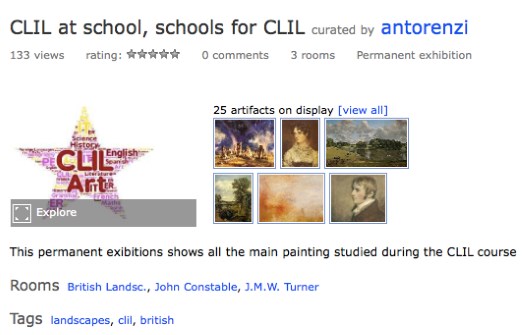

The following example is a project in CLIL and art: a real art exhibition has been organized within a virtual gallery: a 3D environment has been created, where participants get the impression that they are having an immersive world experience.

The project was carried out by a comprehensive school (primary and lower secondary) named “ISA 12 Santo Stefano di Magra” (La Spezia) (it can be consulted here: www.comprensivosantostefanoisa12.it; the exhibition by A. Renzi is available here: http://antorenzi.artsteps.com/exhibitions/23568/CLIL_at_school_schools_for_CLIL).

Fig. 5 – The homepage of the gallery

Once having entered the virtual gallery you can visit it and walk through it. In order to appreciate the paintings and learn more about them, you can click on them and read the explanations provided by the students (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 - The virtual gallery

Fig. 7 - Details about the paintings

Another example of a CLIL project in Art was carried out by some primary school classes engaged in analyzing Kandinsky’s works, singling out their main components: shapes, lines, colours. The students were guided to understand the message Kandinsky wanted to convey about his personal way of conceiving the world. Therefore, they were led to appreciate the connections between art and music, especially to express one’s own feelings and emotions.

As a final project work, the kids realized a poster imitating Kandinsky’s painting, as in Fig. 7. The students are actively engaged in a project, which enhances their enthusiasm, creativity and their aesthetic sense, leading them towards a progressive appreciation of works of art.

(The project was carried out by the Comprehensive School “I.C. Compagni-Carducci” in Florence and is available here: https://epic2016.wordpress.com/emozioni-colori-e-ritmo-nellarte-e-nella-musica/).

Fig. 8 - Making a poster on Kandinsky’s work

The paper was meant to highlight examples of CLIL projects in Art and English, referring to some initiatives carried out by Italian schools and teachers within CLIL projects.

In particular an example of a lesson plan designed by a teacher attending an online CLIL training session co-moderated by the author has been mentioned, stressing the cross-curricular dimension of this kind of project.

Other examples of CLIL projects in Art have been described, considering E-CLIL school networks, engaged in projects on CLIL with the use of learning technologies, as per directions and guidelines provided by the Italian Ministry of Education.

As pointed out in describing these projects, Art can be an ideal subject for CLIL, helping develop students’ creativity and soft skills, together with their language competences and their art sensitiveness.

In the background to the paper some CLIL conceptual frameworks are mentioned, with particular attention to the state of the art of CLIL implementation in Italy.

Ball, P., Kelly, K., Clegg, J., (2015), Putting CLIL into Practice, Oxford University Press.

Cinganotto, L. (2016), CLIL in Italy: A general overview, Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 9(2), 374-400.

Cinganotto, L. (2016) Content and Language Integrated Learning with Technologies: a global online training experience. A report on Techno-CLIL for EVO 2016, THE EUROCALL REVIEW, Volume 24, Number 2, September 2016, pp.56-64.

Cinganotto L., Cuccurullo D. (2015), The role of videos in teaching and learning content in a foreign language, Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, v.11, n.2, 49-62.

Coyle D., Hood P., Marsh D., (2010), CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Eurydice, (2017), Keydata on teaching languages at school in Europe:

http://eurydice.indire.it/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Key-Data-on-Teaching-Languages-2017-Full-report_EN.pdf

European Commission, (2014), Improving the effectiveness of language learning: CLIL and computer assisted language learning:

http://ec.europa.eu/languages/library/studies/clil-call_en.pdf.

Fontecha, Almudena, F. (2010), The CLILQuest: A Type of Language WebQuest for Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). CORELL: Computer Resources for Language Learning 3, 45-64.

Geddes, M., White, R. (1978), The use of semi-scripted simulated authentic speech and listening comprehension, Audio-Visual Language Journal, XVI, pp.137-145.

Genesee F., Hamayan E., (2016) CLIL in context, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Grundy, P., Bociek, H., Parker, K. (2011) English through Art, Helbling Languages.

Hattie, J.A.C., Visible Learning, Routledge.

Hockly, N. (2016), Focus on learning technologies, Oxford University Press.

Hockly, N., Clandfield, L., (2010), Teaching Online: Tools and techniques, options and opportunities, Guildford, Delta Publishing.

Langé, G., Cinganotto, L., (2014), E-CLIL per una didattica innovativa, I Quaderni della Ricerca n.18, Loescher: www.laricerca.loescher.it/quaderno_18/#/4/

Marsh D., (1994), Bilingual Education & Content and Language Integrated Learning. International Association for Cross-cultural Communication, in Language Teaching in the Member States of the European Union, University of Sorbonne, Paris.

Mehisto, P., Frigols, M.J., Marsh, D., (2008), Uncovering CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning and Multilingual Education, Macmillan, Oxford.

Stanley, G., (2013), Language Learning With Technology: Ideas for Integrating Technology in the Language Classroom, Cambridge University Press.

Please check the CLIL for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical Uses of Technology in the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical Uses of Mobile Technology in the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Multiple Intelligences course at Pilgrims website.

|