TESL Instructional Materials and First-Generation Learners: Voices of the Voiceless

J. John Love Joy, India

J. John Love Joy is an Assistant Professor of English at St. Joseph’s College (Autonomous), Tiruchirappalli, India. He has a Post Graduate Diploma in Teaching of English (PGDTE) and an M. Phil. in English Language Teaching from English and Foreign Languages University (formerly CIEFL). He holds a PhD in ELT from the University of Madras. In his eight-year of teaching English, he has co-authored two books on ELT, published research articles and trained in-service teachers. His interests include action research and creative writing. E-mail: johnljoy(at)gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

The context of TESL

The role of learner-investment

Limitations of textbook writers

The voiceless learners

Background of the study

Statement of the problem

The study

The voices of the study

Conclusion

Bibliography

Instructional Materials (IMs) carry with them certain attitudes which are either favourable or biased towards learners and learning contexts. Often these attitudes are hidden either intentionally or unintentionally by the writers of IMs to promote specific perceptions on gender, class, ideology, faith and society. The First-Generation (FG) learners are often silent victims of such promotional attitudes because the textbook writers tend to largely ignore the contexts which represent the culture of FG learners. The fact that the IMs are devoid of relevant cultural contexts is a cause of worry since it impacts the learners’ psychology who may feel excluded from the learning context creating a gap between them and the target language. Gradually, the gap widens with time as these learners climb up the educational ladder. This paper studies the extent of learner-alienation and its impact on FG learners’ learning English as a second language.

The context of language instruction is a complex domain which involves at least eight factors. Apart from the teachers and the learners, a second language teaching-learning context is driven by language theories, acquisition theories, instructional materials, teaching methods, classroom settings and testing practices. We know that these factors exist only to assist learners acquire the target language for their personal, social and career purposes. However, the importance given to these factors have changed from time to time.

We shall trifurcate the history of TESL into linguistic, communicative and contextual eras. The linguistic era, as Brown (1991) observes, is “centrally concerned with issues surrounding the linguistic description of languages and their pedagogical applications.” (p. 255). So, the interests of textbook writer feature nowhere near to that of the learners’ interest other than providing some grammar items followed by rote learning of the same. The materials are produced on top-down process where the learners have the least say in the selection of materials which promote teacher dominance especially through narrative monologues. Freire (1990) comments on this process as follows:

Narration (with the teacher as narrator) leads the learners to memorise mechanically the narrated content. Worse still, it turns them into ‘containers’, into receptacles to be filled by the teacher. The more completely he fills the receptacles, the better a teacher he is. The more meekly the receptacles permit themselves to be filled, the better learners they are. (p. 45)

In this era, the mechanics of the teaching context does not allow the learners to involve and internalise the language input, instead it promotes memorisation of rules through repeated practice. Importantly, the learner is not fully involved in the learning process to internalise and use the language in order to perform communicative functions of the real world.

Contrarily, the communicative era encourages learners to be the co-creators of the learning process with a view to promoting communicative competence through negotiation and autonomy among the learners. Savignon (1991) says, “Today, listeners and readers are no longer regarded as passive partners. They are seen as active participants in the negotiation of meaning." (p. 261). Since learners are not considered a tabula rasa onto which the teachers write their experiences and convictions, they feel, think, create and communicate actively in the classroom. So, the teacher’s role has been modified to that of a counsellor, facilitator and collaborator who position with the learners as “human among humans” (Littlewood 1985: 86). The highlight of this era, therefore, is that the learners are immersed in the learning process, whereby, they personalise the content, complete the task and learn the language by using it.

The contextual era is a period that has moved away from one method to amalgamation of methods. This is a deliberate attempt to stay away from the trap of single method policy to encourage teacher plausibility (Prabhu 1990), so that, the teachers are empowered to adopt relevant and effective method or methods necessitated by the context. Even though, communicative language teaching has advocated learner-friendly classes, it has overlooked the context in which the learning takes place. “CLT has always neglected one key aspect of language teaching – namely the context in which it takes place...” (278) says Bax (2003) because “after all, it is Communicative Language Teaching, not Communicative Language Learning (p. 280: italics as in original). The primary limitation of method-oriented approaches, therefore, lies with the fact that they are preoccupied with attempts of providing teachers with plurality of ideas, whereas, little regard is shown for the context in which the teachers function. When the teachers are faced with a different context, they end up in a conflict because the methodological expectations and the real conditions stay incompatible. Therefore, this method recommends adaptation of theories and techniques belonging to various methods and approaches such as grammar-translation method, the direct method, the oral approach, the audiolingual method, the designer methods, and communicative language teaching.

In order to make the context of learning in tune to the practical difficulties faced by the teachers, Kumaravadivelu (1994) lays out a strategic framework of which cultural consciousness and social relevance are important for our discussion. He says that a teacher has to raise the consciousness of both the native and the target culture among the learners. To begin with, the native culture is recommended, for this may motivate the learners to become socially relevant in the classroom. This “enables practitioners to generate location-specific, classroom-oriented innovative practices” (ibid: 29). Hence, we see that the learners’ culture has attracted attention to suit the post-method conditions because they facilitate learner-investment.

Learning cannot take place unless learners are willing to do so. The three qualities viz., affective attitudes, relevance and culture inclusiveness are looked into in order to encourage active learner participation by contributing substantially to the learning environment. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) rightly points out that “There cannot be any learning unless a person is willing to invest attention.” (cited in Worthy et al. 1999: 12). According to Prabhu (1989) “Learning depends not just on what inputs are made available to the learner in the form of materials, but, equally, on what the learner brings to bear on those inputs, …” (p. 66). This is reflected in the growing interest among the textbook writers’ use of meaningful contexts for language activities. So, the act of producing materials extends itself to accommodate learner-investment by activating the schema of the learners.

Research on learner-investment uniformly suggests that materials that promote life experiences of the learners stand a good chance of initiating learner-investment. Valdez (1999) feels that text which “starts from where the learners are and builds on their knowledge and experiences” (p. 31) can have a higher dependency rate of learning output. Topics and tasks designed to engage learners physically, intellectually, emotionally and culturally result in better learning process. Pemangudi (1995) feels that “Learning materials are more relevant, interesting and motivating if they are structured within the experience, culture and environment of the learner” (p.53). The initiative is to make learners reflect upon their own life and cultural practices while learning a second language. In other words, the IMs used in the language classes should correspond to the experiences of the learners.

India is a diverse country and her classrooms are no different. Textbook writers are very much aware of this fact. The popular practice of materials production is to designate it to a committee which after deliberation and research is expected to compile a textbook to be used by a large number of learners cutting across regional, social, religious and cultural divergences. Addressing the needs of every learner through the IMs is practically impossible, especially while producing materials on a large scale basis, thus compromise is an inevitable part of the process. Consequently, the writers consider every learner unique yet write/compile a textbook that considers everyone as just the same. In other words, the experts decide on a common platform where learners with different language ability, cognitive competence, cultural experience and needs converge. As Maley (1998) observes

A major dilemma faced by all writers of materials, even those writing for small groups of learners with well-defined needs, is that all learners, all teachers and all teaching situations are uniquely different, yet published materials have to treat them as if they were, in some senses at least, the same. (p. 279)

As a result, everyone gets the same text, goes through the lessons in the same order, and at almost the same pace. Not only are the learner-needs compromised as observed by Maley, but also are the relevance, interest and culture compromised owing to the fact that creating customised materials for every individual voice of the course is difficult. Hence the teachers and the learners receive textbooks in which not only are the content, order, and the activities predetermined but also the learners.

Generally, FG learners are inhibitive of speaking an alien tongue. While these learners are found tongue-tied, their counterparts belonging to continuing generation use English at will and have very few problems with the language. It is not that the FG learners are genetically engineered not to learn English but that they are unmotivated by their present educational environment. These learners enter college with very little practice of using English as Penrose (2002) suggests that they “enter college less prepared than their continuing generation peers” (p. 442). Shockingly, they exit the same institution with very little development in terms of the language skills practised. It means that the learners do not involve much in the classroom activities. This, Erickson and Schultz (1982) claim as the systematic silencing of the learners’ voices. It is ‘systematic’ because there is a method in it since for over decades these learners do not get to see their own life reflected in the IMs. It is ‘silencing’ since the FG learners have not felt the urge to voice their opinions both productively and receptively.

This is a transitional period in India with increasing number of FG learners showing more interest in education. The desire to improve their status in the society has had them attend schools in large numbers and work hard to cope with the challenges. Their hard work, to some extent, fruitions in subject-based papers, whereas, with English it is not a satisfactory harvest since language is a skill-based course which demands practice in and out of the classroom. Consequently, these learners fail to impress the employers as their poor English stands between them and the employment opportunities. As we know, most of the employers expect their recruits to have a good command over English. Most of these learners have had their education in regional medium schools and the Study Group (1967) reported the condition of teaching English in such schools as follows:

We have succeeded to some extent in accelerating the enrolment of the learners at school level. But failed to check the deterioration of the standards of teaching English. In the country of Panini, the country that gave the science of linguistics to the world, there are hardly any pupils in our regional medium schools who can write a correct sentence in English. (p. 8)

This observation, though made four decades ago, is relevant in all ways in today’s context as well. Learner enrolment at school level has gone up manifold for the past ten years due to the soaring employment opportunities. Attempts have been made to improve the quality of teaching and learning by introducing activity based learning but the ground realities remain unaltered. Sharma (1989) attributes the deterioration of standards to the “defective textbooks” (p. 22) and this is corroborated by the report given in Development in practice (1997), which confirms that “the reliability of many textbooks is low” (p. 16).

Giving input to the learners who cannot identify with it will definitely have adverse effects on learning since the very context is unreal. This leads to poor language intake by the learners. As Sturtridge (1981) observes, “the more remote the situation and the roles are from the experience of the learners, the more ‘unreal’ the language they use becomes” (p. 127). Subsequently, their output will also suffer as these learners remain silent throughout the learning process. So the whole process of learning, that is, input, interaction, intake and output suffers. This needs to be seriously investigated as learner investment is lacking among the FG learners.

We have discussed that the learners are alienated and silenced because of the generic nature of IMs, and systematic/unintentional neglect of the culture of FG learners. The resulting divergence of learner expectations and IMs is a cause of worry since the gap widens and ends up in the learners’ feeling of being left out of the teaching-learning process. So, the study aims at finding out whether the culture exclusive textbooks contribute to the dismal performance by the FG learners in using English.

In order to verify the claim that the FG learners are silenced, we studied the responses of 122 first-generation college-goers aging between 19 and 21. They were third year under graduates belonging to various disciplines of four colleges in Tamil Nadu, South India. These FG learners had their schooling in regional medium and at the time of our study they were into the fifth semester of their programme. Their exposure to English had been limited to 40 to 60 minutes of daily input by the teacher who might depend solely on the prescribed textbook both at the school and the college level.

A questionnaire comprising four statements was given to the respondents and they were asked to tick the appropriate response from among five choices viz., agree, strongly agree, disagree, strongly disagree and not sure based on their experience with IMs since schooling. The four statements were also given in their mother tongue, Tamil. Furthermore, for better comprehension each statement was explained to them in an objective manner bearing in mind that any evaluative comments would change learners’ response. The four statements are (1) My textbooks dealt with contexts which were closer to me; (2) I was able to identify myself with the characters given in the lessons; (3) I was attached to the language classes on socio, cultural and academic grounds during the language activities; and (4) My textbooks made me feel at ease throughout their use.

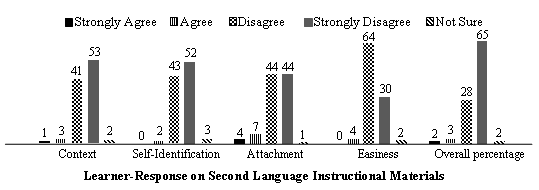

The feedback shows alarming divergence on the relationship between IMs and the FG learners because majority of the learners have disagreed on all the four statements. That is to say that the IMs have had a negative impact on these learners. The responses of the learners are graphed below:

All the leading projections on the graph represent the disagreements of the learners on the usefulness of the General English textbook. The response to the first statement, the strong disagreement and disagreement put together, clearly shows that a mounting 94% do not endorse the idea that the contexts of their IMs are relevant. The same trend is seen for the other three responses: 95% disagree on self-identification, 88% disagree on attachment and 94% disagree on the IMs having made them comfortable. Thus, the overall percentage of learners who are not happy with the IMs is 93%, whereas, only a paltry 5% learners are positive about their opinion on the usefulness of the IMs and 2% of the learners are not sure about the issues mentioned in the questionnaire. It can be construed from the given responses that the disagreements of the learners are high in number and intense in nature that the IMs may gradually lead to negative attitude towards learning English.

Learners are social beings who are influenced by their surroundings. As we know that encouraging environment results in better learning output. Unfortunately, this is not the case with both the social and academic environments of the FG learners. When they see a textbook, its content is strange in many aspects, vis-a-vis, irrelevant themes, remote settings and complex dictions. As a result, the very context of learning disappoints and alienates them. This to a large extent heightens their affective filter and gradually makes them silent spectators.

Learners are not empty vessels devoid of cultural experiences. Textbook writers cannot forever provide inputs that the FG learners cannot identify themselves with. The responses of the study are also suggestive of the expectations of the FG learners who yearn to discuss their own domain and people. It is, however, difficult to accommodate every concern of the learners when IMs are produced on a large scale. In such case, the cultures, experiences and interests of the learners belonging to various sectors of the society can be used judiciously. Moreover, teachers can also create activities by localising the context to suit the schema of the learners. However, they may still need required expressions to convey their feelings. In this regard, the teachers can design appropriate pre-tasks to provide them with necessary language input. This may create what Davies (2006) states “opportunities for self-expression”. If this be the case, learners could involve in the language activities inside the classroom. Thus the unwarranted silence of the learners can be rectified and their voices be heard in the classrooms.

IMs need not be considered as something planned for and done to the learners. It must be perceived as an effort planned and done with the learners, so that, they feel important and worthy. IMs are not always an objective presentation of texts but an opportunity for social practice. We need to understand that the FG learners are low only on the proficiency level of the target language, whereas, they are very high on their societal experiences. It is, therefore, imperative on the part of the textbook writers to incorporate the experiences which are closer to hearts of these learners, so that, they communicate the alien tongue through their hearts much more meaningfully.

Bax, S. 2003. The end of CLT: A context approach to language teaching. ELT Journal, 57/3: 278-287.

Brown, H.D. 1991. TESOL at Twenty-Five: What are the issues? TESOL Quarterly, 25/2: 245-260.

Davies, A. 2006. What do learners really want from their EFL course? ELT Journal, 60/1: 3-12

Development in Practice. 1997. Primary education in India. Delhi: A World Bank Publication and Allied Publishers Ltd.

Erickson, F. and J. Schultz 1982. Learners’ experience of the curriculum. in P.W. Jackson (ed.) Handbook of Research on Curriculum. New York, Macmillan: 465-485.

Freire, P. 1990. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. (4th ed.) Translated by M.B. Ramos. London: Penguin Books.

Kumaravadivelu, B. 1994. The Post-method Condition: (E)merging Strategies for Second/Foreign Language Teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 28/1: 27-48.

Littlewood, W. 1985. Communicative Language Teaching: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maley, A. 1998. Squaring the circle – reconciling materials as constraint with materials as empowerment. in B. Tomlinson (ed.) Materials Development in Language Teaching. Cambridge, CUP: 279-294.

Pemangudi, J. 1995. Using newspapers and radio in English language teaching. Forum, 33/3, p. 53.

Penrose, A.M. 2002. Academic literacy perception and performance: Comparing first-generation and continuing-generation college learners. Research in the Teaching of English, 36: 437-461.

Prabhu, N.S. 1989. Materials as support: Materials as constraint. Guidelines, 11/1: 66-70.

Prabhu, N.S. 1990. There is no best method – Why? TESOL Quarterly, 24/2: 161-176.

Savignon, S.J. 1991. Communicative language teaching: State of the art. TESOL Quarterly, 25/2: 261-278.

Sharma, R.K. 1989. Problems and solutions of teaching English. New Delhi: Commonwealth Publishers.

Sturtridge, J. 1981. Role play and simulation. In K. Johnson and K. Morrow (eds.) Communication in the classroom. London: Longman.

Teaching of English. 1971. The Report of the Second Study Group. New Delhi: Ministry of Education, Government of India.

Valdez, M.G. 1999. How learners’ needs affect syllabus design. English Teaching Forum, Jan-Mar: 30-31.

Worthy, J, M. Moorman, M. Turnes. 1999. What Johnny likes to read is hard to find in school. Reading Research Quarterly, 34/1: 12-27.

The Building Positive Group Dynamics course can be viewed here

|