Using Pictures and Picture Books to Create Readers and Thoughtful Readings

Janice Bland, Germany

Janice Bland’s specialization as a teacher educator is primary and lower secondary. Janice co-ordinates the school-internship, a central part of the M.Ed at Hildesheim University, Germany. Her other commitments in the English Department include Children’s and Young Adult Literature for on-going English teachers, Creative Writing, Drama in Education and Introduction to Literary Studies. E-mail: janice.bland@uni-hildesheim.de

Menu

Developing language and aesthetic awareness

The contribution of picture books to children’s personal growth

Sophisticated content but often very few words

Irony and visual literacy

Friends in children’s books

Fairy tales and larger-than-life characters

Intercultural literacy

Using the full potential of a picture book

Conclusion

References

Children’s earliest experience with literary texts is of the utmost importance. Literary picture books can provide a stress-free beginning. Practising the skill of visual literacy means searching for meanings in pictures, and interpreting what the pictures tell us. Children are good at finding meanings in pictures, and teachers can help children discover their abilities – whereby giving them confidence and pleasure in books.

Of the several approaches to using picture books, one well-established approach focuses on their usefulness as a scaffolding context for language learning. The verbal text is seen as central, the pictures as motivating and supportive. A verbal text that is pattern-driven (e.g. with repetition and rhyme) and therefore predictable will effectively aid children’s language acquisition (Linse 2006, 75-77). A second approach focuses specifically on the pictures and the development of the child’s aesthetic awareness. Fine arts picture books, such as those by the current Children’s Laureate, Anthony Browne, are recommended for cross-curricular teaching in the primary school, and in the secondary school for subject-based bilingual teaching: art through the medium of English (Rymarczyk 2006, 139).

A third approach is based on concepts of reader-response theory, and the contribution of picture books to children’s personal growth. “Literary” literacy, i.e. taking pleasure in reading between the lines, is a vital complement to functional literacy, learning to read and write. The research behind this approach is centred on L1 and L2 education as well as foreign language learning. Children talk their way into literacy in English, with the help of the mother tongue where necessary. Along the lines of this approach, I would like to consider five literary picture books. Strange as it may seem, the case for regarding picture books as literature rests largely on the pictures, or on the interplay between pictures and words. Looking at complex pictures, children wonder, compare, discover, infer and comprehend. “These are central concerns of literary reading, the need to infer, which is a key skill for all learners to develop more widely” (Hall 2005, 21). To encourage this skill, teachers can choose picture books that suggest different meanings and interpretations.

There’s more to reading than decoding signs on the page.

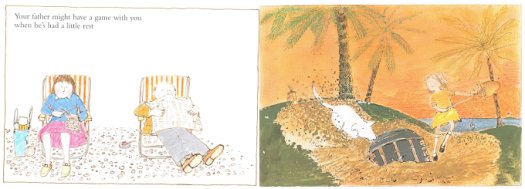

Picture books with sophisticated content often have very few words, such as the classic picture book Come away from the water, Shirley (Burningham 1977). Shirley’s adventure story – a picture narrative without words – is shown on the right-hand pages. Burningham, in common with other postmodern picture book authors, creates a puzzle with a verbal text that opposes Shirley’s story. So the mother’s banal verbal commentary, illustrated by realistic pictures on the left-hand pages, enriches our understanding of Shirley’s need to escape and live in her own fantasy world. The mother speaks the stereotypical clichés of a sadly unimaginative older generation. Her pictures show her sitting, knitting and serving coffee from a thermos flask. The father is seen smoking his pipe, reading his newspaper and then falling asleep. Their seaside setting is very empty, which suggests they live in an empty world. Mother and father sit passively in their folding beach chairs as if watching a film. They see absolutely nothing of Shirley’s exciting, cinematic play. Her adventures are with dangerous pirates and buried treasure, with a dog as her comrade, against a richly contextualized background of golden sands, dark seas and wild skies. When children guess at why Shirley disappears into a fantasy world of her own – where she fights pirates and steals a treasure map – and when they fill in the details of her adventures, they are learning to interpret the gaps, to “read between the lines”. Picture books such as this are “multi-layered”; the reader is invited to read and re-read them, each time discovering something new. This puts the young readers in charge of the story, and children often out-perform the teacher in discovering clues in the pictures. Children gain pleasure in their insightful response to literary texts.

Picture books with little or no verbal text offer many opportunities for creative language work, e.g. inventing speech balloons such as Look! Here’s the treasure!! Help me! Come on, let’s dig! It’s heavy! It’s gigantic! It’s gold!! Careful! Whoops… Re-creating is creating: writing a new dialogue is a way of enacting the construction of meaning. Come away from the water, Shirley is anti-authoritarian both formally – as an open, ambiguous text – and thematically. The teacher may like to introduce this charmingly ironic nursery rhyme, which matches so well the theme of the picture book:

Mother, may I go and swim?

Yes, my darling daughter.

Fold your clothes up neat and trim,

But don’t go near the water!

The competence of visual literacy means an awareness of how pictures may influence and manipulate the viewer. An understanding of irony, saying one thing, and meaning something else, is valuable training in critical insight. This can be achieved very graphically through the dual-coding of picture books, when there is a gap or discrepancy between the story told by the pictures, and that told by the verbal text.

...central to the picture book is the notion of the readerly gap – that imaginative space that lies hidden somewhere between the words and the pictures, or in the mysterious syntax of the pictures themselves, or between the shifting perspectives and untrustworthy voices of the narratives. (Watson/Styles 1996: 2)

Gaps encourage thinking skills: this gives children the opportunity to create meaning. Irony always requires the reader/viewer to participate by creating the full, composite text, which does not appear on the page but only in the reader/viewer’s response. As this kind of picture book demands participation, it is ideal for group reading. An example of this kind of text is THE TRUE STORY OF THE 3 LITTLE PIGS! (Scieszka & Smith 1989). This picture book is suitable for a literature class in the early years of the secondary school, provided the children have already learned to take picture books seriously as literary texts in the primary school. There is an unreliable narrator, A. Wolf. He turns the pigs into the villains in a retelling of the traditional tale. The wolf protests his innocence: the destruction of the pigs’ houses was not due to his appetite, but rather to the foolishness and unneighbourliness of the three little pigs.

So I went next door to ask if I could borrow a cup of sugar. Now the guy next door was a pig. And he wasn’t too bright, either. He had built his whole house out of straw. Can you believe it? I mean who in his right mind would build a house of straw? (Scieszka 1989)

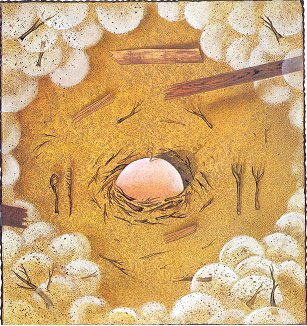

Although the pictures, like the words, are from the point of view of A. Wolf, details have slipped in which betray the wolf narrator’s real intentions with regard to the little pigs. The above page from THE TRUE STORY OF THE THREE LITTLE PIGS! illustrates the aftermath of the wolf’s distruction of the house built of sticks. A. Wolf maintains his innocence – he only sneezed a great sneeze… And you are not going to believe this, but the guy's house fell down just like his brother's. When the dust cleared, there was the Second Little Pig - dead as a doornail.

A careful examination of the illustration, however, reveals that the blowing down of the house and the death of the Second Little Pig was not the accident A.Wolf claims. Discovering all of these details requires careful re-readings of the pictures, comparison of findings and associations, and revisiting the verbal text for discrepancies and contradictions.

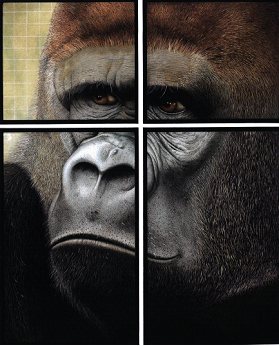

Primary school children cannot yet read J. K. Rowling (or Salman Rushdie, Michael Morpurgo, Anne Fine, David Almond, Philip Pullman… to mention just a miniscule number of the many outstanding writers who also write children’s fiction). There are, however, splendidly colourful friends in children’s literary texts with their own bewitching and moving stories. A series of lessons I was able to witness recently – delivered by a graduate student in Lower Saxony for her M.Ed. thesis – focused on Exploring the use of picture books in a foreign language class: Zoo (Anthony Browne) in the Hauptschule, 5th grade (Möhle 2008). The children in this class, typically for a Hauptschule, were entirely inexperienced with regard to reading (including reading picture books) for pleasure. We can assume most of these students associate books with school-learning – a domain where they experience failure as a rule. Zoo (Browne 1992) is a landmark picture book. It combines outstanding pictures with a serious examination of the relationship between man and animals, and the concept of keeping animals in cages. The 11 and 12-year-old students in this class, with the guidance of the teacher, were well able to grasp the messages to be found in the pictures, and enjoyed this experience of deep reading. Some of the children were able, even in this short sequence of lessons, to discover the contradictions between the dialogue spoken by a rather thoughtless family at the zoo and the close-up images of the very beautiful and very beleaguered animals. The emotional power of Zoo is due to the persuasive pictures, encouraging even the inexperienced reader to bond with the silent animals, and – given sufficient time – achieve a critical distance to the squabbling human visitors at the zoo.

Fairy tales epitomise the non-canonical nature of children’s literature, which has always been made up of truly great stories as well as odds and ends, bits and bobs, like the countless popular nursery rhymes. Fairy tales belong to folk culture, exist in different retellings, and demonstrate admirably how stories may mean different things to different people at different times. Children can begin to learn at an early age that there is not only one way to interpret stories, there are no absloute meanings in texts, just as there is never only one way to translate from one language to another. This gives children some independence from the authority position of the teacher, and some command over their own learning.

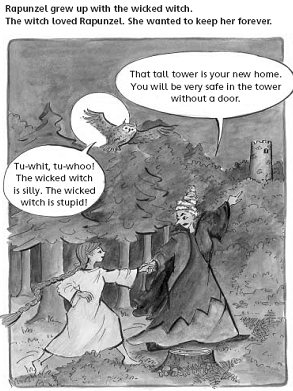

First and foremost it is necessary to motivate children to read at all. This is where the sparkling, larger-than-life characters of children’s stories can help. Perhaps it is the excessive nature of many characters and stories that makes them so appealing. Rapunzel with golden hair so long that a wicked witch, and handsome prince, can climb up the tall tower using her hair as a rope; a slimy frog, an ugly beast and a great bear who turn into handsome princes; Sleeping Beauty who sleeps for one hundred long years and Jack who climbs a beanstalk so high it reaches up to the clouds… One way of reading Rapunzel may be to highlight the destructive power of possessive and selfish love, a theme children need to begin to understand, and can handle when woven within a story. Children need not be linguistically overchallenged when much of the meaning is conveyed in the pictures.

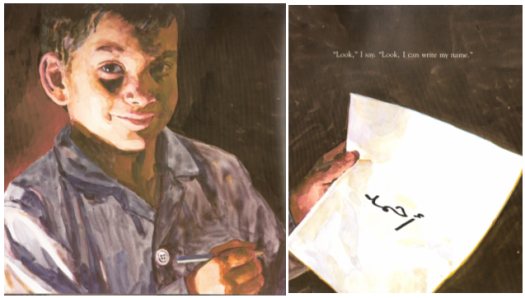

Interaction with picture books – above-all with the pictures – becomes a key to unlock new understanding. Authors leave gaps to fill with the confidence that the young reader will be an imaginative, tolerant and creative addressee, giving time generously and with as yet few cultural prejudices. Literature is a highly expressive carrier of cultural meaning. For this reason the attention to detail and accuracy in the pictures is of prime importance; this, along with aesthetic value, is the hallmark of quality picture books. The book The Day of Ahmed’s Secret (Heide & Gilliland 1990) presents pictures of colourful and noisy Cairo streets, crowded with people, camels, cars and carts. Ahmed is a young delivery boy, and the reader follows him through his busy day, while he thinks:

All kinds of sounds, maybe every sound in the world, are tangled together: trucks and donkeys, cars and camels, carts and buses, dogs and bells, shouts and calls and whistles and laughter all at once… Loudest of all to me today is the silent sound of my secret, which I have not yet spoken.

A detailed collage is created through the colours and characters, ancient buildings and modern transport in the pictures of Cairo. The story shows us Cairo through Ahmed’s eyes:

I buy my beans and rice, and sit in the shade of the old wall. My father has told me the wall is a thousand years old, and even our great-great- grandfathers were not yet born when it was built… I close my eyes and have my quiet time, the time my father says I must have each day. “If there are no quiet spaces in your head, it fills with noise,” he has told me.

At the end of a long day, Ahmed returns home to his family. He tells his very special secret to his whole family, that has been waiting for him. It is dark and the lanterns are lit, and Ahmed takes a deep breath and speaks the ceremonious words: “Look”, I say. “Look, I can write my name.” From the secret mentioned in the title, a secret that is kept throughout the hectic working day, to the darkness and solemnity of the last pages, the picture book sends messages about the energy of the young, the need to believe in the wonder of education, and how magnificent the first steps to literacy are.

Students of a minority ethnic background in our schools may experience constant devaluation of their cultural identity. A possible measure against this in primary schools is to introduce e.g. original Turkish or Arabic picture books in the language class. As the pictures rather than the verbal text are often central to the story-telling and intercultural dimension, there is good reason to include authentic picture books from diverse cultures in the English lesson. As English is a lingua franca, it makes sense to go well beyond the Anglophone world for intercultural input.

Picture book characterisation is often additionally developed through “the unique possibility to elaborate with close-ups, so that we literally can come closer to characters and almost feel as if we were talking to them” (Nikolajeva 2003: 44). The careful narrative technique of quality picture books is cinematic: holding up a picture book to a large class that can hardly see the pictures is not the way to use its potential, as most of the story is told by the pictures. Fortunately publishers are beginning to provide DVDs (best projected in class onto a large screen) with their bestselling books. Sometimes animation is added “to bring the picture book to life”. This fascinates children and provides a wonderful few minutes (the DVDs are very short), however the class certainly becomes more passive when watching moving pictures. Young readers need their imagination, their individual and reciprocal response and sufficient time to linger over details, to fill the silences between the pictures with their own ideas and bring the best picture books to life. However when children are swept along in a current of fast-moving and fragmented electronic images, we can hardly expect them to take in much of the world flashing them by.

The word/image interplay in picture books help children learn visual literacy – and not to confuse representations with reality. Creative participation in children’s literature is the best training for literary literacy – taking pleasure in inferring and discovering. In a pleasurable way students learn to have confidence in their own interpretative response. Children’s earliest experience with literature is of the utmost importance: literary picture books can provide a wonderful beginning. Many picture books demand and entice re-readings, and anticipate a slightly different creative response at each interaction. They are ideal for the mutual forming of ideas and constructing of meaning in a community of readers. For these reasons, young learners take naturally to children’s literature and will – given the opportunity – form the habit of reading.

Bland, Janice, illustrated by Lottermoser, Elisabeth (2008). Fairy Tales: Rapunzel. Braunschweig: Westermann.

Browne, Anthony (1992). Zoo. London: Random House.

Burningham, John (1977). Come away from the water, Shirley. London: Random House.

Hall, Geoff (2005). Literature in Language Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Linse, Caroline (2006). “An analysis of predictable picture books: some beginning insights”. In:

Enever, Janet & Schmid-Schönbein, Gisela (eds): Picture Books and Young Learners of English. München: Langenscheidt. 71-79.

Möhle, Manuela (2008). Exploring the use of picture books in a foreign language class: Zoo (Anthony Browne) in the Hauptschule, 5th grade. Unpublished M.Ed. thesis, Hildesheim University.

Nikolajeva Maria (2003). “Picturebook Characterisation: Word/image Interaction”. In: Styles,

Morag & Bearne, Eve (eds) Art, Narrative and Childhood. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books. 37-49.

Rymarczyk, Jutta (2006). “Which fine arts book for which type of cross-curricular classroom?” In:

Enever, Janet & Schmid-Schönbein, Gisela (eds.): Picture Books and Young Learners of English. München: Langenscheidt. 137-149.

Scieszka, Jon, illustrated by Smith, Lane (1989). The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs! London: Puffin.

Watson, Victor & Styles, Morag (1996). Talking Pictures. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

The Methodology and Language for Primary Teachers course can be viewed here

|