The Lexical Approach and Spoken Grammar: Developments in Language Analysis and Their Pedagogical Implications

Hanna Kryszewska, Poland

Hanna Kryszewska is a teacher, teacher trainer, trainer of trainers and mentors, author of resource books and course books, senior lecturer at the University of Gdańsk, Poland, director of Studies at the University of Social Sciences SWPS, Sopot, Poland. She co-wrote the following books: “Options for English” - PWSiP, 1991, “Learner-based Teaching”, OUP, 1992, “Reading on Your Own”, PWN 1995, “Towards Teaching”, Heinemann International 1995, “Stand-by Book”, ed. Seth Lindstromberg, CUP 1996, “Observing English Lessons” -A Video Teacher Training Course, „ForMat Intro, 1, 2 and 3” a course for senior secondary level, Macmillan Polska 2001” and “ Language Activities for Teenagers” CUP ed. Seth Lindstromberg, and ’’The Company Words keep’’ DELTA . Expert reviewer of course books for the Polish Ministry of Education. Presenter at national and international seminars and conferences worldwide. Since February 2006 editor of website magazine Humanising Language Teaching. E-mail: hania.kryszewska@pilgrims.co.uk

Menu

Summary

Introduction

Grammar versus lexis

Words change

Word partnerships: multi-word chunks

From lexis to grammar

Two grammars

Pedagogical implications

References

The Lexical Approach is a way of thinking about language which puts before grammar. Lexical phrases (Nattinger and DeCarico) or lexical chunks (M. Lewis) are seen as the crucial building blocks of the language which ‘prime’ certain grammar (M. Hoey). The emergence of this new way of thinking about language coincided with the development of new tools to examine the facts of language we speak and write. Computer analysis of the language corpus has provided invaluable information about: the meaning of words, their frequencies and their word partnerships, etc... The analysis of corpus data has revised many long held beliefs about grammar and lexis, also leading to the distinction between Spoken and Written Grammar, not to be confused with register. The pedagogical implications for ELT are immense and the new way of thinking is already finding its way into our course books and other teaching materials.

In the last two decades we have seen major changes in the way we view language, which potentially has great implications for the way we teach or could teach language. Linguistics, psychology and broadly understood philosophy have influenced the way we view language and approach language teaching. We owe to psychology the following teaching methods and approaches: the Audio-Lingual Method, Humanism, Cognitivism along with Teaching across the Curriculum (LAC) and Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), Social Constructivism, Suggestopaedia, the Theory of Multiple Intelligences and Neuro Linguistic Programming ( NLP) for classroom use, just to name a few mainstream and alternative approaches and methods which have implemented our knowledge about the way we believe human brains and emotions work when learning a language.

Computational analysis of the language is far removed from psychology and is closely related to linguistics. Linguists along with lexicographers and grammarians analyse the language corpora yielding data about the language. The body of data is made available to us in the form of various corpora, for example, the British National Corpus (BNC) which, according to the most recent data, contains 200 million words of English texts of various genres fed into the computer and then analysed. The results are facts that come to light, often surprising ones, about the English language which need to be interpreted and need to or should be taken on board in teaching the language. Of course, there is a second option which some academics strongly believe in is that these facts could be ignored. My view is that the latter is no option because the findings of corpus research are very impressive and have already been making their way into conferences, publications, lexicography and even course books as well as everyday classroom practice (Kryszewska 2003).

Lexicography has benefitted form corpus analysis in the most visible way. No respectable publisher would these days consider publishing a dictionary which is not corpus based, for example Macmillan English Dictionary – MED (2002), Oxford Dictionary of Collocations (2002) or Macmillan Phrasal Verbs Plus 2005). The real problem for pedagogy of English Language Teaching (ELT) is that it is very difficult to make teachers and publishers of mainstream course books take these new developments on board. Teachers often feel threatened believing that the knowledge of the language they possess is no longer relevant and valid. In the case of non native teachers years of hard work to master the language seem to be wasted. Naturally if teachers fear change resistance to change occurs so they are not willing to adopt a progressive course. Consequently publishers play safe because they want to sell their courses to a big group of customers. It is a vicious circle. What is more, publications like The Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written Language, (1999) or Cambridge Grammar of English (2006) offer a formidable body of data that is too extensive for a course book writer let alone for an ordinary language teacher to take on board. Besides what is often voiced as a concern is that grey areas of grammar are revealed if not legistimised by the corpus, i.e. a language mistake in the traditional view of the language classroom. In corpus analysis language in this case English is as a collection of facts about the language and there is no value of right or wrong attached to them, for example ‘my bestest friend’ or ‘I have less friends than you’ are accepted and have high frequency of occurrence. More often than not teachers and learners of the language want clear, black and white rules, and are resistant to ambiguity or relativity. Facts revealed by the corpus analysis like ‘would / ‘d’ in the meaning of ‘used to’ being five times more common than ‘used to’ or the fact that the word ‘happened’ is usually preceded or collocates with ‘nothing’ or ‘something’ make an interesting revelation at a conference, but are perceived by teachers as of no immediate relevance to everyday classroom practice and language teaching. It is the role of believers in corpus analysis who are experienced teachers, course book and materials writers, syllabus designers and academics to find a way to bridge this gap and make the best use of the body of language data available to us. In this paper I will outline a few problem areas and solutions in the form of practical activities.

In the traditional approach to language teaching grammar plays a key role. Grammar accuracy is usually a sign that the language has been mastered well. However, now we believe that lexis or lexical chunks are of primary importance as outlined in a few groundbreaking publications ( Nattinger, DeCarrico, 1992) (Lewis, 1993). The question remains how teachers and learners can be persuaded that this is the case. The answer is designing activities which illustrate the point and can be used with low level students, for example (Kryszewska 2003, Davis, Kryszewska, 2004):

Activity 1

Ask the students to act out a dialogue from a modern play: ( Saunders, 1974)

- Hey!

- Hm?

- Catch!

- Thanks.

- Eat!

- Catch.

- Thanks.

- Eat.

- Catch.

Discuss the amount and balance of meaning and grammar.

Discuss the role of intonation.

You can do it in the native language of the students.

Activity 2

Ask the students to write their own one word dialogues following the text in Activity 1.

For example:

- Try.

- No.

- Try!

- No!

- Try!!

- OK.

- Good?

- Good.

- Good!

Then the students themselves or other students act the dialogues out.

Discuss the importance of a single words and intonation.

Activity 3

Ask the students to act out a dialogue about, e.g. their last weekend.

Allow the use of single words or phrases, but no grammar structures, e.g. tenses.

Ideally, does this exercise before the students have learned any past tense in English.

- Your weekend?

- Nice.

- A party?

- Yes on Friday.

- Me too.

- Where?

- Galaxy.

- Me too.

- Wow!

- Good music.

- Yes, absolutely!

Discuss the importance of intonation and ability to communicate without grammar.

These exercises show the students and the teachers that communication can take place without grammar. They also illustrate the importance of a single word and a lexical chunk.

Another area we can explore through computer analysis of the language are the changes in the meaning of words and how words and meanings evolve. Language is a living matter and changes all the time therefore this is issue should also be addressed in a language class. In this paper I focus on some of the tendencies and propose classroom activities which are built around certain phenomena. The first one is the tendency in English to reduce single words as a result of shared knowledge, to write phrases or whole sentences as one word. The two kinds of new ‘words’ can often be found in authentic texts and usually not to be found in dictionaries, for example some lexis in novels written by Graham Swift. Students who are likely to be exposed to authentic texts come across an obstacle difficult to overcome even if they have access to reference materials. However, this issue can easily be addressed as a classroom activity and as part of learner training.

Activity 4

Ask the students to decode the following words.

fab

ta

bril

gator

croc

mod-cons

jag

mag

Allow the use of dictionaries.

Allow the use of other sources, e.g. goggle

If they still have problems decoding the words ask them to use common sense.

Finally, provide contexts where and when these words might be used.

Finally give the students the correct answer.

Activity 5

Give the following headline.

Ask the students to decide what the article is about

Discuss the various ideas.

As a clue tell them the article about the wrong kind of dishes served in American canteens.

Finally give the correct answer: Carbohydrates in the cafeteria.

Activity 6

Ask the students to decipher the following words.

a wannabe

whodunit

kind-a one sided

Dukeavedim

Presunidestates

Tell them they are written as you hear them

Discuss the interpretations and give the answers.

Practice correct pronunciation.

Activity 7

Ask the students to decipher the following sentences. (Swift, 1997)

Whaddayaknow?

Whassemater?

Yerallright.

Frechrissakes!

Whadjergonnado?

Whossat?

Omigod!

Howzit going?

Tell them they are written as you hear them

Discuss the interpretations and give the answers.

Practise correct pronunciation.

Activity 8

Ask the students to listen to a song.

Once they have understood it well ask them to write chunks and whole sentences as they hear them.

Compare the results.

I tried it with a Dire Straights song: Calling Elvis. It worked like magic. The lines the students came up with were:

Amhisbigestfan

Caniaieaveamesage

Isanybdyhome

Canicometothephone

The original lines are:

I am his biggest fan.

Can I leave a message?

Is anybody home?

Can he come to the phone?

The second phenomenon regarding the changes words undergo is a characteristic feature of the English language called ‘verbing’, which is the tendency to take any English word and change it into a verb. A cartoon character once commented on this phenomenon by saying ‘Verbing weirds language’. However, quite the opposite is true; it makes language more precise and helps it to describe or name new phenomena in the language or in life.

Changes in the language occur very fast, in response to the speakers’ needs. Therefore both teachers, especially non native ones, and learners need to accept and enjoy the fact that language is dynamic and subject to constant change. When they are aware of the tendency, they can predict the meaning of the new verbs, for example ‘to greenlight’, ‘to text’ or ‘to google’ or even they may begin to ‘verb’ themselves, in this way being creative and making the target language their own property. Recently a colleague wrote to me in an e-mail: ‘This is a good poem. You could HLT it.’ meaning ‘You could publish it in Humanising Language Teaching’. That day Simon Marshall created a new English verb which I have already started to use, e.g. on the phone to a friend I said ” Today I am HLT-ing”. Within a short period the verb was used in the infinitive, then in the Present Continuous tense and soon will be used in the Simple Past tense as a regular verb naturally. We can also predict that it is transitive.

In the language classroom we can introduce this phenomenon, through activities like the one given below:

Activity 9

Dictate the following words to students

she

Mr. Brown

to and fro

handbag

out

Ask them to write sentences with these words, the first ones that come to their minds.

In my experience they will use

she as a pronoun

Mr. Brown as proper name

to and fro as prepositions

handbag as a non

out as a preposition

Then tell them these words all can be verbs, e.g.

Don’t she me!

Don’t Mr. Brown him.

Mrs. Thatcher used to handbag the Ministers

Waiters always to and fro.

This journalist can out anybody, she did it to Elton John.

Ask the students to predict what these verbs mean and in what broader context they are used.

Ask them to decide if these verbs are regular or irregular and how they would behave in other forms than the infinitive. Discuss if it is correct to say

He shees me!

She Mr. browned him.

Mrs. Thatcher handbagged the Ministers

Waiters are toing and froing.

This journalist outed Elton John.

The third phenomenon worth introducing to language learning is presenting new words and showing the mechanisms how some of the new words are created. Apart from the language content of an activity focusing on the creation of new words, we also introduce an element of culture. Like in the case of ‘verbing’ we need to create activities which will help students make friends with change and which will introduce the students to the tools that help overcome the potential obstacles, this time also using the access to websites offering data suitable and understandable for laymen. (Kryszewska 2006)

Activity 10

Ask the students to brainstorm what the words below mean.

nimbyism _________________________________________________

macjob _________________________________________________

dianabilia _________________________________________________

Encourage the use of various resources, e.g. dictionaries, the Internet Discuss the various outcomes and research results.

Present the definitions from a dictionary where such words and their history can be found, e.g. The Oxford Dictionary of New Words (1991), Frantic Semantics (2000), More Frantic Semantics (2001)

Activity 11

Give students some new words and their more old fashioned equivalents

nimbyism hypocrisy

macjob a poorly paid job

dianabilia Princess Diana’s memorabilia

Ask the students to decide which word is more often used in English, i.e. which one has a higher frequency.

Tell to students to go on www.googlefight and see which word appears more often on the web.

Discuss the results and the reasons for these figures.

Make sure the students record their results.

After a few weeks ask the students to check the results. Since the figures on the web change all the time it is a way to see if certain words are getting more popular or not.

The fourth area is the historical content of a word. Certain words or lexical chunks often refer to a special period in the past or signpost a period in which they were created or became popular. Very often, at present, their lexical frequency is too low for them to be included in dictionaries. The only dictionaries that may contain such words are dictionaries like Twentieth Century Words (1999). Activities which focus on such words introduce and explore the cultural and historical content contained in the word. They are good lessons on culture and history; also an opportunity to show the tendencies in language and lexis.

Activity 12

Ask the students to decide when these words entered the English language

__ miniskirt __ cultural revolution __ tarmac __ gigolo __ blarite

Students do not have to name the exact date but they have to arrange the words chronologically.

Encourage the use of various resources, e.g. the Internet, reference books, etc.

Introduce the students to the Twentieth Century Words – Dictionary (1999) and other similar sources

Activity 13

Ask the students to work in groups and design their own activities for other classmates using similar sources as in Activity 12.

Make available all possible reference materials.

The term ‘word’ has now been replaced with the term ‘language chunk’, which in essence can be a single word, collocation, now usually referred to as ‘word partnership’, a fixed expression, which is more than a collocation, or can even be a whole sentence of fixed type, called a ‘routine’. Word partnerships provided by corpus analysis of the language are explored by grammarians and lexicographers through concordances like the ones below.

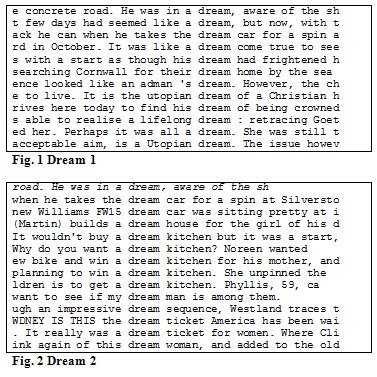

However, such concordances have relatively little appeal to students although there have been some attempts to use them in class for learner training and developing language awareness and to build language activities around concordances (Adrian Underhill, 2002). The problem is that when concordances are used in the language class the lesson focus is strictly on lexis or grammar with relatively little language skills focus. Therefore it is much more advisable to use in class ‘Simple Search’ tools on corpus websites for example www.britshnationalcorpus to find example sentences containing the chunk we are interested in. The 15 sentences below focus on the same word ‘dream’ as in Fig. 1 and Fig.2. Students can deduce the meaning and usage of the word ‘dream’, working with full sentences and a wider context I which they appear. The teacher can use these sentences not only with lexical tasks but also with tasks focusing on various reading sub skills, register and genre identification, speaking etc., for example using the following sentences containing the same word ‘dream’ like in Fig.3.

Results of your search

Your query was

dream

Here is a random selection of 15 solutions from the 4468 found...

1290 You can dream and dream but only what happens in this room night after night is important.

1776 It is difficult to react adequately to George Woodcock's silly comment that in Leonard's first two books of poetry `;the thirties urge to relate the imagery of poetry to the world we live in, as the world we dream, might never have existed.';

124 To buy a Stag just for its investment potential is to deny yourself the sort of al fresco luxury that most people can only dream about in a new car.

1784 Even the revolution was unreal --; `;By agreeing to go first with the Panthers and then with the Palestinians, playing my role as a dreamer inside a dream, wasn't I just one more factor of unreality inside both movements?'; (p. 149).

1813 Detachment, self-consciousness must be flooded out by the stream of consciousness --; music caught in its own flux, a white water of dream language (REM, Muses).

648 We can't give away Sue and Richard's dream home, but we can offer BBC Gardeners' World Magazine readers a taste of the good life.

202 Whether it was being referred to that week as The Tea Room, The Oasis or The Hole (I liked that one too), it was always basically night inside, A Good Night Out; not black as jeweller's velvet exactly, except on a good night, but always when you stepped in off the street it was truly night inside, a night dark enough to dream in and on which to meet strangers, whatever the variations on where and when this particular night had fallen.

656 South Africa's dream rudely shattered

27 A panel of judges will read all the entries, and the chosen one will win the tank they need, plus cabinet and hood from AQUARIUMS, CABINETS AND HOODS and up to £150 worth of fishkeeping equipment

4903 THE featherweight domestic dream fight is on after a `;put-up or shut-up'; challenge from Barney Eastwood to Frank Warren to complete their dream set-up.

1881 The girl who wanted to make movies is watching her dream come true.

630 I walked out of the champagne tent in a dream or, rather, a nightmare and put two elderly customers, who were coming towards me and were obviously intent on a reviving glass or two, in peril as I blundered into them.

812 With them, chemists have been able to fulfill a long-standing dream: the direct observation of the motions of atoms as molecules undergo reactions.

385 After New Jack City 2 , Ice is due to make The Looters , directed by Walter Hill, another dream mix of ingredients (gangs, ghettos, firemen and buried treasure).

|

Fig. 3 Dream 3

The fact that now many of us we believe lexis is more important than grammar is a fact many teachers and learners find hard to accept. Again we need to design activities which will illustrate the point and convince those who doubt it (examples in Activity 14 and Activity 15 after Pinker 2001).

Activity 14

Ask the students to fill in the grid and write the verb forms of the following verbs.

If the students ask what the words mean, refuse to give an answer and refer them to dictionaries.

| infinitive | past | past participle |

| shine | | |

| cost | | |

| weave | | |

| speed | | |

If in doubt as to the verb forms, students may confer with a fellow student or use reference materials.

In my experience students will give the following answers:

| infinitive | past | past participle |

| shine | shone | shone |

| cost | cost | cost |

| weave | wove | woven |

| speed | sped | sped |

Overreact and tell the students they are wrong, very wrong.

Say you had something completely different in mind and show the students the other possibility where all the verbs are regular.

| infinitive | past | past participle |

| shine | shined | shined |

| cost | costed | costed |

| weave | weaved | weaved |

| speeded | speeded | speeded |

Ask the students to research the differences in meaning.

Discuss the implications and stress the fact that the students chose the grammar before they decided on the meaning.

Activity 15

Ask the students to complete the following grid.

| singular | plural |

| mouse | |

| little foot | |

| corpus | |

Discuss the results.

Then ask them to fill in this grid

| singular | plural |

| mouse | |

| computer mouse | |

| Mickey Mouse | |

| little foot | |

| Mr. Litllefoot | (Mr. and Mrs. L. ) The |

| corpus | |

| language corpus | |

Compare the answers, discuss the outcomes and pool ideas.

Key:

| singular | plural |

| mouse | mice |

| computer mouse | computer mice |

| Mickey Mouse | Mickey Mouses |

| little foot | Little feet |

| Mr. Litllefoot | The Littlefoots |

| corpus | corpora |

| language corpus | Language corpuses/corpora |

The major doubts that teacher voice is the relationship between lexis and grammar. The answer has been provided by Hoey (2005) in his concept of priming. Lexical items and their meaning demand certain grammar, e.g. ‘next Christmas’ primes a future tense or future reference e.g. ‘I will…, I will be +ing, I am going to…’ and ‘last Christmas’ a past tense but not ‘used to’. Similarly the ‘If I were you…’ primes the phrase ‘I’d…’ and the phrase ‘cat’s whiskers’ meaning ‘important’ roughly primes a structure ‘He/she/they/ you think he/she/they/you are/is/was/were cat’s whiskers’. One cannot say ‘I think I will be cat’s whiskers’. Learners need to be trained how to recognise chunks in context and how to use them properly (Lewis, 1997). The activity below illustrates the point:

Activity 16

Ask students to brainstorm what word/s follow the words ‘afraid’.

They will most likely come up with the following words

to

afraid that

of

Tell them the ones below are possible options too

on

at

afraid with

without

from

Ask students to come up with sentences where the above combinations are possible Discuss the students’ ideas and implications of the exercise.

Another major development of corpus analysis is the emergence of two grammars of English, the Written Grammar and the Spoken Grammar (Carter, McCarthy, 1997). Now we realize that for many decades when we taught language, we taught written grammar also for spoken discourse. Sometimes intuitively our students would use chunks of various lengths to communicate and teachers insisted on full and complete sentences, following the rules of Written Grammar. Now we phenomena like ellipsis, hedging, backchannelling, false starts and many others have been named and described by Carter and McCarthy (1997). As I have said the students have also been aware of the various possibilities and tried to use spoken grammar in exercises to discover the key in the book required a different answer than the on they have come up with. Take the following grammar exercise from a 1984 course book (O’Connell) in which students have to fill in the missing words. There can be various outcomes depending if we follow the rules of Spoken or Written discourse.

Example 1

A: ___________________ a decision yet about where you’re going on holiday?

B: Yes. _________________ of going to Greece.

A: Lucky you! This time next week you ____________ the beach.

B: Actually, sunbathing____________ to me at all.

A: _______________ rather see the sights instead then?

B: No. What _____________ is sailing.

A: I wish you __________ before.

B: Why?

A: Because sailing’s my hobby, too, but up to now there _______ to go with me.

The correct answer in the course book key was along these lines:

Example 2

A: __Have you made _______ a decision yet about where you’re going on holiday?

B: Yes. _I have been thinking________ of going to Greece.

A: Lucky you! This time next week you ____will be lying on ________ the beach.

B: Actually, sunbathing _____doesn’t appeal _______ to me at all.

A: ___Would you ____________ rather see the sights instead then?

B: No. What __I like _______ is sailing.

A: I wish you ______had told me ____ before.

B: Why?

A: Because sailing’s my hobby, too, but up to now there ____has been no one willing___ to go with me.

However, some students, especially those who have had much contact with native speakers, would come up with answers along the rules of Spoken Grammar, answers which the key would consider as wrong ( Kryszewska, 2003). Here are their answers:

Example 3

A: ______Made_____________ a decision yet about where you’re going on holiday?

B: Yes. __Thought_______________ of going to Greece.

A: Lucky you! This time next week you _____… on_______ the beach.

B: Actually, sunbathing ____is nothing________ to me at all.

A: __Would_____________ rather see the sights instead then?

B: No. What _____matters________ is sailing.

A: I wish you ____’d said______ before.

B: Why?

A: Because sailing’s my hobby, too, but up to now there __’s been no one willing _____ to go with me.

The teacher might have a dilemma which answer to accept, follow the key or common sense. Considering the exercise is a dialogue between two speakers in an informal situation, solutions in Example 3 are far more suitable.

Take another example from a 1992 course book in which learners are to correct mistakes in the following sentences.

Example 4

- I have usually my hair cut when I go for an interview.

- He drives a green small car German.

- Quietly I’ve been today sitting in the sun.

- I when I arrived found a place was full of hooligans horrible.

- He is a dustman very intelligent who very well dances.

- English I studied in London in a language school.

- I can recommend for children a good film.

- Alison drove off last week quickly.

The source of the sentences and context is not specified in the instruction. If we treat these sentences as samples of written discourse they need to be corrected, however if we treat them as samples of spoken language all of them are or can be correct if the intonation is appropriate and there is enough pausing and a bit of drama, like in real life.

Another consideration is whether teachers should introduce students to terms derived from the realm of Spoken Grammar, the matalanguage of Spoken Grammar as described by Carter and McCarthy (1997):

- Adverbs

- Back-channeling

- Deixis

- Delexical verbs

- Discourse markers

- Ellipsis

- Fixed expressions

- Fronting

- General words

- Heads

- Tails

- Tags

- Hedges

- Modality

- Vague language

- Interactional

- Transactional

I believe that if we feel comfortable about introducing other metalanguage terms like ‘ the Present Perfect Tense’, ‘inversion’ or ‘modal verbs’ then we should not hesitate to introduce terms derived from the realm of Spoken Grammar. The major benefit is that when giving feedback to students on their spoken language performance we can precisely name their good or weaker areas by saying: ‘ Good hedging but work on fillers’.

Again to help students master the use of the above terms we need to design activities, for example:

Activity 17

Choose a popular song with many features of Spoken Grammar, for example Heavy Fuel by Dire Straits.

Design a variety of activities around the lyrics.

In one of them focus on Spoken Grammar.

First introduce or remind the students of the features of Spoken Grammar and the various terms.

Then ask them to identify some of the features.

Then ask them to rewrite fragments containing these features following the rules of Written Grammar.

The concern teachers voice when they are presented with various facts about the real language yielded by corpus analysis is accuracy, preparation for exams and tests as well as the marking scheme. Usually, whether the students sound naturally or write like native speakers is not their concern. A solution to this dilemma is provided by Scrivener (1994) in the ARC model ( Authentic, Restricted and Clarification model), which is a perfect compromise reconciling the Spoken and Written Grammar in a language. My suggestion is that teachers introduce the ARC model to their students and then clarify every time any doubt arises as to which mode discourse at the given moment is in focus: Authentic or Restricted. Then there is no problem when students come up with real life examples like ‘It don’t impress me much’, ‘I can’t get no satisfaction’ or “I have done it yesterday’ and insist these are the correct answers in a test or exam.

To illustrate the issue of clarification with regard to authentic use we may use songs, e.g. Heavy Fuel by Dire Straights or You and Me by No Doubt, modern plays (Saunders), dialogues or even narration in recently written novels (Swift) (Kryszewska 2003).

Authors of course books, supplementary materials and resource books, syllabus designers and experienced teachers face the problem of how to incorporate the impressive body of data made available to us by linguists and lexicographers. There is a great need to make these findings accessible, user friendly and unthreatening both to the students and ordinary teachers. Above all we need to convince them that these findings and our ideas how to implement them contribute to better results in language learning and are a major factor in learner training. There has been a significant body of publications on the subject, among others in the website magazine Humanising Language Teaching (Rundell, O’Dell, Kryszewska, Davis, Rinvolucri et al.). Some course books have already taken on board the idea of chunks, e.g. Innovations (2000), corpus analysis of the language, student corpus and simplified concordances, e.g. Inside Out-Intermediate (2000) and the issue of Spoken Grammar, e.g. Landmark – Upper Intermediate (2000). However, some publishers tend to claim in their course blurb that the course book is corpus based, just because there is an element of work on collocations treated in a very traditional way. The main message of the paper is that the more effort is taken the sooner the true findings of corpus analysis of the language will be widely implemented to the benefit of our learners.

a. Books

Biber et al, 1999. The Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written Language. Longman.

Carter, R. and M. McCarthy, 1997. Exploring Spoken English. Cambridge University Press.

Carter R. and M. McCarthy, 2006. Cambridge Grammar of English. Cambridge University

Press

Hoey, M. 2005. Lexical Priming. A New Theory of Words and Language. Routtledge.

Lewis M, 1993. The Lexical Approach, LTP.

Lewis, M. ed. 1997. Implementing the Lexical Approach. LTP

Morrish, J. 2000. Frantic Semantics. Pan Books.

Moorish, J. 2001 . More Frantic Semantics. Pan Books.

Nattinger J. Jeanette DeCarrico, 1992. Lexical Phrases and Language Teaching. Oxford

University Press

Pinker, S. 2001. Words and Rules. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Scrivener, J. 1994. Learning Teaching. Heinemann

Underhill A. 2002. Macmillan English Dictionary – Workbook. Macmillan

b. Dictionaries

Macmillan English Dictionary.2002. Macmillan.

Macmillan Phrasal Verbs Plus. 2005. Macmillan.

The Oxford Dictionary of New Words. 1991. Oxford University Press.

Twentieth Century Words. 1999. Oxford University Press.

Course books

O’Connell, S. Focus on CAE, 1984. Longman

Deller, H. and D. Hocking. 2000. Innovations. LTP

Bell, J., R.Gower. 1992. Upper Intermediate Matters. Longman

Hanines, S. and B. Steward. 2000. Landmark – Upper Intermediate. Oxford University Press.

Kay. S. and J. Vaughn. Inside Out - Intermediate, 2000. Macmillan

c. Journals

Davis, P. and H. Kryszewska. 2004. Chunking for Beginners. Humanising Language Teaching vol. 6 issue 1

Kryszewska, H. Chunking for language Classes. GRETA. Revista para Profesores de Inglés 10 (2): 27-30.

Kryszewska, H. 2003.Why I won’t say goodbye to the Lexical Approach. Humanising Language Teaching. vol. 5 issue 4

Kryszewska, H. 2006 vol. 3. Lexical Chunks Offer Insight into Culture. Humanising Language Teaching.

d. Internet documents

The British National Corpus, www.bnc

www.googlefight

e. Other

Dire Straights. Calling Elvis. Song by Dire Straights. Album: One Every Street

Dire Straights. Heavy Fuel. Song by Dire Straights. Album : On Every Street

No Doubt, Song : You and Me

Saunders, J. 1974. After Liverpool.

Swift, G. 1997. Last Orders. Vintage

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology for Teaching Spoken Grammar and English course at Pilgrims website.

|