Editorial

Republished by permission from

http://leoxicon.blogspot.com/2013/10/dave-willis-lexical-syllabus_4913.html

Remembering Dave Willis: We are Lexically Indebted to Him

Leo Selivan, Israel

Image source:

www.willis-elt.co.uk

I opened my Facebook yesterday morning and was saddened to see Chia Suan Chong’s post about the passing of Dave Willis. I went over to Twitter and the feed was already filled with RIPs and condolences. For most in the ELT world Dave Willis’s name is associated with Task-Based Learning. But his contribution to lexical approaches to language teaching is just as outstanding. In fact, his pioneering work on the first Lexical Syllabus predates Michael Lewis’s seminal book by three years, the main difference between the two being words as a starting point for Willis and collocations for Lewis.

In the late 1980s Collins published a new EFL textbook co-authored by Dave Willis and his wife Jane. The book was an outcome of the COBUILD (Collins Birmingham University International Database) project – at that time the biggest and most significant attempt to compile a corpus of contemporary English. Simply titled Collins Cobuild English Course, the book was based on a very simple premise: most common words in English, such as do, get, it, way carry most important patterns in the language.

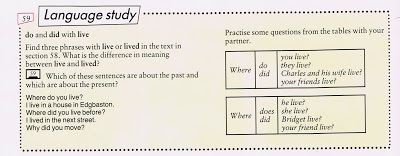

Instead of following the usual course of carefully sequenced, item-by-item presentation of the verb To be, followed by the Present Simple, then Present Continuous and other “usual suspects”, the book focused on the meanings of the most frequent words and highlighted patterns associated with them. At the lowest level – there was a total of three – it offered exercises such as this:

When I was in charge of the book stock and teachers’ resource room at the British Council I was lucky to stumble across two dusty copies of the student’s books- Level 1 and 2 – and “save” them when the teaching centre closed down. Looking at the coursebook now, more than 20 years after it was published, one can see why the ambitious series wasn't the runaway success it should have been. Authentic unscripted dialogues full of false starts and pauses, interspersed with erms and mhms with native speakers interrupting each other while engaging in various tasks was too radical a departure from the conventional coursebook format. Add to that things like “At eight o’clock I’m just leaving my house”, “At one o’clock I am normally eating my lunch” (Oh horror! It should be Present Simple!) and the conspicuous absence of traditional grammar labels would surely appear outlandish, if not bizarre, to an ELT practitioner at that time. Mind you, it was the time when the Present Perfect didn’t appear until Unit 6 of the Intermediate level and the texts were carefully vetted to make sure an “unknown” structure hadn’t slipped in to distract the learner’s attention from a specific grammar point being expounded.

Image source:

www.oxfam.org.uk

A couple of years later, Willis published a book about the book. The Lexical Syllabus (1990), which is a must read and re-read for any English teacher, was basically about the process of writing the coursebook. Willis describes the rationale behind the groundbreaking coursebook and explains why they chose to focus on 700 most common words – fresh corpus evidence had just come in that these 700 words constitute 70% of English text. The fact that such a small number of words accounts for a very high proportion of English text “shows the enormous power of the common words of English”, states Willis (1990: 46). Using these as a starting point and doing away with the grammar syllabus, the Willis's English Course still covered all the “traditional” grammar points (Present Simple, Conditionals, Modal verbs) and then some. It also highlighted many features of spoken grammar which were absent from textbooks around that time, for example that for pointing back (So we did that one first. That was the easy one), as for when/while (Chris draws a rough map as Philip talks), such patterns as go and… (Shall we go and see a film?), to do with (e.g. anything to do with sport) etc. And I hope it wouldn’t be speaking out of turn to say that the idea behind the coursebook was what inspired Scott Thornbury’s Natural Grammar which was built around a similar principle: focusing on the "small words" of English and highlighting patterns associated with them.

The Lexical Syllabus, which you can find online in its entirety on the Birmingham University website, has a chapter which particularly stuck with me where Willis scrutinizes three features of pedagogic grammars:

- The Passive voice

- The Second conditional

- Reported speech

and concludes that they have needlessly been elevated to the status of syntactic structures and should instead be treated lexically. Three years later, Lewis (1993) would go on to claim that these labels – together with Will as the future tense - should be abandoned from grammar books altogether not stopping short of calling them “nonsense”. But it was Willis who first pointed out that English is a lexical language:

It is perhaps particularly unfortunate that English has for so long been described in terms of a Latinate grammar derived from a highly inflected language, when English itself is quite different, a minimally inflected language. Obviously I would not claim that there is nothing more to English than word meaning, but it does seem that word meaning and word order are central to English in a way that may not hold true for other languages.(Willis 1990: 23, my emphasis)

Dave Willis at IATEFL Glasgow 2012, Photo by Chia Suan Chong

In his IATEFL Harrogate 2010 talk What do we mean by 'grammar''?, which I was lucky to listen to live (I also enjoyed a nice chat with Dave at a reception that evening), he insightfully noted that we spend an awful lot of time on teaching “easy” aspects of grammar and largely leave the learner to work out truly difficult bits by themselves. As an example he gave multi-part verbs which can be separable (look smth up or look up smth) or inseparable (look after smb) - a real minefield for a teacher! Interestingly, students somehow pick them up without our involvement – have you ever heard a student say “look somebody after”? So can we really claim that we teach grammar if all we do is select the easy bits – and spend on them an unproportional amount of class time - while casually avoiding truly complicated areas?

It is for insights like this, his criticism of the grammatical syllabus and innovative approach to language teaching that I consider Willis a lexical pioneer to whom we owe a debt of gratitude.

References

Lewis, M. (1993). The Lexical Approach: The State of ELT and a Way Forward. Hove: LTP

Willis, D. (1990). The Lexical Syllabus. London: Collins

|