Editorial

The article first appeared in a special issue of the ETAI Forum 2013, celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Lexical Approach.

Putting Into Practice: Supplementing the Syllabus with the Study of Chunks

Helen Osimo, Israel

Dr. Helen Osimo is a retired lecturer in Applied Linguistics in the English Department of

Oranim Academic College. Her Ph.D. thesis is in the two fields of Mitigation (Pragmatics)

and Formulaic Language. This paper draws on a course she has given for several years to

pre- and in-service teachers. E-mail: helen.osimo@netvision.net.il

Menu

Introduction

What are idiomatic lexical chunks

Explicit instruction or authentic exposure?

Criticism of explicit instruction

Adopting and adapting vocabulary research and pedagogy

Supplementing the syllabus: a sample unit

Summing up

References

The importance and benefits of incorporating lexical chunks in language teaching has been well-documented. This paper demonstrates how a sub-set of lexical chunks – idiomatic lexical chunks (ILCs) – can be integrated systematically into a general syllabus, by grouping them according to common components.

I will briefly discuss what counts as an idiomatic lexical chunk and then show how strategies promoted for vocabulary acquisition can be applied to the explicit study of idiomatic lexical chunks.

But first a true anecdote which serves as a criticism of relying on authentic exposure –as opposed to explicit instruction – for the acquisition of ILCs.

In the English Department at Oranim all interaction is conducted in English. In one of my lessons a couple of years ago, I was forced to express my dissatisfaction that many students in that class were not reading the set academic material. I spoke for several minutes about the importance of reading background material, and, with a modicum of irritation, I ended my brief discourse by saying:

“Have I made myself clear?”

Two or three days later my colleague in the department reported on a meeting she had had with a student from the same group. She had asked the student to explain the content of her essay which my colleague had found confusing. The student explained step by step to her lecturer what she had meant. And then finished by saying

“Have I made myself clear?”

The student had noticed and memorized the form of this lexical chunk through natural exposure but she had used it literally and incorrectly. She had not been explicitly taught the function – that this was in fact an idiomatic chunk generally expressing a reprimand with definite pragmatic restrictions of a reprimand!

In my terms idiomatic lexical chunks are neither full and totally opaque idioms, such as someone let the cat out of the bag, which is colourful but relatively rare. Nor are they transparent grammatical chunks, such as Who has been eating (my porridge)? which are highly frequent, promote fluency, but are rule-governed and systematic. The following is my definition of ILCs based on Wray (2002:33):

an idiomatic lexical chunk is a multiword unit that is (i) grammatically irregular, that is, at least one component does not follow regular grammatical rules. Irregularity includes fixedness and grammatical constraints, such as all being well; by and large; come to think of it;

and/or

(ii) semantically opaque in varying degrees, that is, at least one component in the unit does not convey its conventional meaning, such as [make] up [your] mind; [it] [has] nothing to do with; it [occurs] to me.

Why is there an ongoing debate on whether to teach lexical chunks explicitly or to rely on authentic exposure? The case in favour of relying on authentic exposure, and thus hoping for incidental learning, is based on first language (L1) acquisition research, which indicates that for the native speaker formulaic sequences (lexical chunks) are stored holistically in the mental lexicon, along with single-word vocabulary items, and retrieval by native speakers is automatic. Therefore any sort of analysis is artificial. (Wray 2000:463).

My foregoing illustration of incidental learning through authentic exposure regarding have I made myself clear, demonstrates only too well the risks in relying fully on exposure.

On the other hand, there is increased evidence for explicit instruction with regard to single-word vocabulary items: Carter & McCarthy (1997), Lewis (1997), Nation (2001), Schmitt (1997, 2000), Laufer (2005), among others. A closer look at Batia Laufer’s proposition for vocabulary learning eminently suits the teaching of idiomatic lexical chunks:

Planned Lexical Instruction (PLI) …ensures noticing, provides correct lexical information, and creates opportunities for forming and expanding knowledge

through a variety of word focused activities. Laufer (2005: 311)

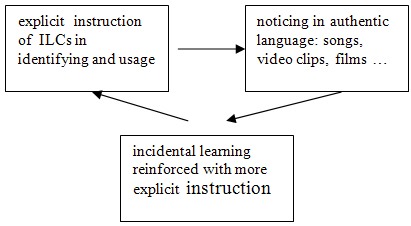

PLI combines the instruction of lexical forms and their meanings together with ‘noticing’ and thus allows for the role for incidental learning through exposure. My experience is that once learners are made aware of the phenomenon of idiomatic chunks, they start noticing them everywhere – in the songs, video clips, films etc. – that pupils are rigorously exposed to today. Raising pupils’ awareness to the widespread usage of ILCs goes a long way towards teaching them. The following flow-chart illustrates the adaptation of PLI.

While the balance is in favour of explicit instruction, it is worthwhile learning from criticism:

high-priority chunks need to be taught … [but] the ‘new toy’ effect can mean that formulaic expressions get more attention than they deserve, and other aspects of language--ordinary vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation and skills--get sidelined. (Swan, 2006:5)

Taking into account all of these points relating to vocabulary acquisition, I suggest a six-point ‘planned lexical instruction’ for the teaching of ILCs which are by nature a highly disorderly language phenomenon.

- Organise chunks into manageable teaching clusters as a mnemonic device, where one component may be constant. For example cluster chunks around the verb get or take:

get on [my] nerves; get rid of; get in touch with; get used to;

Cluster chunks according to known grammatical structures, for example time adverbials:

occasionally: once in a while; now and again; from time to time;

or if structures: if I were you I’d [V]; if you like; if you happen to [V]

- Prioritize by selecting high frequency items (using a corpus) and/or items relevant to learners’ needs.

- Focus on identifying: Idiomatic chunks are, by definition, difficult to identify and learners have a lot of trouble at first in identifying. Exercises in identifying provide opportunities for noticing so it is important that criteria are made clear and a extensive practice is given in identifying them in context.

- Provide lexical information: The use of L1 translation, (Nation 2001:351) and bilingual dictionaries (Schmitt, 1997: 219) are sometimes possible for idiomatic chunks. There are some chunks with word for word Hebrew translations and this is a useful place to start. Otherwise paraphrase and extensive exemplification are crucial.

- Link new knowledge to old. The main way of doing this is by “finding some element already in the mental lexicon to relate the new lexical information to” (Schmitt, 2000: 132).

This is more relevant in chunks than in vocabulary acquisition, because chunks are composed words that are high frequency and often very familiar to the learner. Clustering them provides a framework for teaching and eases the burden on memory for learning.

- Reinforce and move from receptive to productive skills

Create opportunities for reinforcement through multiple encounters with a variety of activities focused on idiomatic lexical chunks.

The following applies the above six-point planned lexical instruction to the teaching of a sub-category of chunks – “modal chunks” – which are chunks where one component is a modal verb. Such a unit can be well-integrated into a unit teaching modal verbs from a grammatical standpoint. Modal auxiliaries are highly frequent in English but meanings change according to tense and context. Sometimes it is easier to learn the chunks which contain modals that to give rules about these changes in meaning.

The ILCs in this unit are those that occur with would, can, could, and might

Before getting into the 6-point plan, it is necessary to check whether “modal chunks” meet the above criteria of being idiomatic. Modal chunks are different from grammatically regular patterns of modals. The modal auxiliary is not optional and not variable; it is a fixed part of the chunk and therefore fits the criterion of having grammatical restraints. Compare

I can/can’t/couldn’t see the lake from my house.

with

I couldn’t care less about seeing the lake.

but not

- I can’t care less

- I can care less

- I could care less

- I can care more

The following is a list of ‘modal chunks’ which also fit at least one of the foregoing criteria, together with their frequency rates (explained below) and are to be subjected to the six point check list of planned lexical instruction:

(i) Organize chunks into manageable teaching/learning clusters

- [I] would like (1,987)

- [I] would rather (547)

- would [you] mind [asking] (174)

- as luck would have it

- [I] could do with ((433)

- [I] couldn’t care less

- [I] can’t help [thinking] (207)

- that can’t be helped

- [I] can’t be bothered with (382)

- [I] can’t stand

- [we] might as well (994)

(ii) Prioritize: select high frequency items.

Frequency searches on the British National Corpus (BNC) yielded the above numbers of occurrences for each chunk. The BNC is a 100 million word collection of samples of written and spoken language. Two words per million is considered high frequency in research on chunks, therefore 200 occurrences is the frequency threshold. Those that do not meet the frequency threshold have been included not only for their relevance to the needs of our learners, but also for the ease with which an equivalent Hebrew chunk can be found.

(iii) Focus on identifying

Read the text and find 8 chunks with modal verbs.

What a surprise

Maya, Tammy and Ben have stayed in the classroom for a chat during the break; their best

friend Ruthie is going away for a year with her parents on their sabbatical leave.

Maya: I would like to make a surprise party for Ruthie as she is leaving. We need to have it when all the class can come.

Ben: Well, as we are nearly at the end of the year, we might as well wait until the summer holidays.

Maya: O.K. How about the first Saturday in the summer holiday? Now where should we have it – in one of our houses or on the beach?

Ben: Oh, I would rather have it on the beach

Tammy: Yes, me too.

Maya: If we’re going to have it on the beach, we could do with some help from the parents. We’ll need to take the stuff down by car.

Tammy: Right! I’ll volunteer my parents. Then we’ll need music. Ben, would you mind bringing your guitar?

Ben: Great idea! You know, I can’t help thinking that Ruthie may not want a really big party. She’s quite a shy person in crowds.

Maya: Oh that can’t be helped – I know she’ll love it after the first shock. Everyone loves a beach party!!

As luck would have it, just then Ruthie walked into the classroom! Her friends suddenly stopped their conversation.

Ruthie: Hi guys! I’m so glad I’ve caught the three of you together. My parents have told me they want to throw a goodbye party for me at the end of the year – I wanted you to be the first to know!

|

(iv) Provide lexical information: translate or paraphrase

Copy the modal chunks next to their meanings (which are in jumbled order)

I prefer _________________ I keep thinking ____________________

we need _________________ unfortunately or fortunately_________

I want ___________________ do you object? ____________________

we can’t avoid that_________ this is a reason to (do something) _____

The equivalent Hebrew chunks are more helpful than the paraphrase

(v) Link new knowledge to old

Here are three more chunks with can’t and couldn’t with their meanings:

- I couldn’t care less about …I really don’t care

- I can’t stand ... I hate …

- I can’t be bothered with … I won’t make the effort

(vi) Reinforce …

(I) Read the dialogues about the party; underline the modal chunks and their meanings.

- Ben: Would you rather have pizza at the party or hamburgers?

Ruthie: Oh, I prefer pizza. Everyone likes pizza.

- Tammy: There’ll be a terrible mess as there will be a lot of people

Ruthie: That can’t be helped – it’s a class party.

Tammy: Yes, we can’t avoid a mess. Don’t worry – we’ll stay and clean up.

(II) Answer the questionnaire about parties (circle the one closest to your view!)

- What is your view of surprise parties?

- I would much rather know about my party.

- I would like a surprise party.

- I can’t stand surprise parties.

- What kind of food is best for parties?

- I would rather have snacks than real food.

- I couldn’t care less about the food.

- Everyone likes pizza so you might as well have that.

- Do you like playing games at parties?

- I can’t be bothered with games; I prefer to dance.

- I can’t stand games; they’re usually childish.

- I would rather not play games; I’m a bit shy.

and move from receptive to productive skills: The second-hand cloze (Laufer & Osimo 1991)

III. Here is an email that Ruthie is sending to her cousin Dalia telling her about

the party. Complete the gaps with the modal chunks you have learned.

Hi Dalia,

I am having a going-away party on 5th July and I (1) __________

to invite you. Bring your things to sleep over – we (2) ________

make a whole weekend of it. I’m a bit worried about the music. I

think we (3) __________ more disks, so (4) __________ bringing

some of your latest ones?

Bye for now, Ruthie

I have proposed the criteria of grammatical irregularity and semantic opacity for establishing what counts as an idiomatic lexical chunk and for identifying them in texts. I have also briefly made a case for providing explicit instruction over relying on exposure. The strategies for promoting explicit instruction for single-word vocabulary acquisition are itemized and a sample unit demonstrates how these strategies can be applied to the teaching and learning of idiomatic lexical chunks.

The motivation for the methodology is the aim for raising awareness of our learners to this very prevalent phenomenon. More than other areas of language, awareness of idiomatic chunks is a crucial step in acquisition. There are thousands of idiomatic chunks in English; many are opaque in meaning, they have erratic variability and restrictions. We cannot aim for near-native usage or accuracy as with grammar and we cannot efficiently supply service lists as for vocabulary. We can, however, aim for thorough knowledge of high priority items, and we can feature them sufficiently in the syllabi so that learners will develop awareness and notice that idiomatic chunks are indeed everywhere in the language they hear and need.

Carter, R. & McCarthy, M. (1997). Exploring Spoken English Cambridge: C.U.P.

Laufer B. & Osimo H. (1991). Facilitating long-term retention of vocabulary: The second hand cloze. System, 19, 3, 217-224.

Laufer, B. (2005). Instructed second language vocabulary learning: The fault in the ‘default hypothesis’. In Hausen A. & M. Pierrard (Eds.) Investigations in instructed second language acquisition (pp 311-329). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lewis, M. (1997). Pedagogical implications of the lexical approach. In Coady, J. & T. Hucklin, Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition (pp 255-270). Cambridge: C.U.P.

Nation, I.S.P. (2001) Learning Vocabulary in Another Language: Cambridge, C.U.P.

Schmitt N., (1997) Vocabulary learning strategies. In Carter, R & M. McCarthy Vocabulary: Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy, Cambridge: C.U.P

Schmitt, N. (2000) Vocabulary in Language Teaching, Cambridge: C.U.P.

Swan M (2006) Chunks in the classroom: Let's not go overboard. Teacher Trainer 20(3), 5-6

Wray, A. (2000) Formulaic Sequences in Second Language Teaching: Principle and Practice. Applied Linguistics, 21(4), 463-489.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology for Teaching Spoken Grammar and English course at Pilgrims website.

|