The Stagger Lee Project

Simon Andrewes, Spain

Simon Andrewes is a semi-freelance, semi-retired, semi-unemployed language teacher based in Granada, Spain, where he also leads cultural tours related to the life, times and work of the poet-playwright Federico Garcia Lorca. E-mail: simon@granadalabella.info

Menu

Introduction

The earliest blues version

Mississippi John Hurt’s “Stack O’Lee Blues” and Woody Guthrie’s “Stackolee”

The Bad Man Mythology

Taunting White Authority

Lee Sentenced and Hanged

Stetson Symbolism

The Leap from Stagger Lee to Rosa Parks

Lloyd Price’s “Stagger Lee” (1958)

Genesis

Rosa Parks

Anticipatory Celebration

And the Walls Came Tumbling Down

Price’s Reinvention of Stagger Lee

The Elements of the Stagger Lee Story

Follow-ups

Bibliography

Acknowledgement

Links

The December 28, 1895 edition of the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat reports the shooting in a crowded bar of William Lyons by Lee “Stag” Sheldon in the course of a drunken argument during the Christmas festivities.

The legend of Stagger Lee was born, one of the most remarkable and enduring tales emerging from the African-American oral tradition and merging with mainstream American folklore.

In the course of the twentieth century the story was retold and reinvented many times and given musical expression in all the genres of the popular American tradition: classical blues, rhythm & blues, jazz, boogie woogie, country, folk, soul, punk and rock & roll, as well as ska and reggae.

Successive versions reflected the changing African-American consciousness on the way from subservient second-class citizen barely freed from a slave mentality through the human rights movement to full political freedom and equality before the law.

This article suggests ways how the Stagger Lee legend can be incorporated into the sociocultural component of the English class at Secondary level.

The St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat report can be read here [A]. It is copied from “The AKA Blues Connection's Stagger Lee Files” authored by Jim Hauser (contact: jphauser2000@yahoo.com) at

www.geocities.com/blueskat2000/stagger_lee_home.htm

Students may be asked to respond to a series of true-false statements [B]. These statements draw attention to facts which are relevant for the way they are included, omitted, or changed in subsequent interpretations of the story.

Musical versions of the incident were in circulation by the first decade of the twentieth century but it wasn’t until white people got interested in blues that the first recordings were made. One of these was Furry Lewis’s 1927 recording “Billy Lyons and Stack O’Lee”. In the oral tradition, as we will see, Lee’s name changed many times: Stack O’Lee, Stackolee, Stackalee, Stackererlee, Stagolee, Stagger Lee…

Lewis' style is typical of the Memphis blues style of the 1920s. The value of a song is in the story it tells. The simple lyric is backed by hypnotic repetitive riffs and subtle slide guitars. Lewis's soft voice and quick slide work are particularly effective. He was a frequent visitor to the recording studios in the late 1920s and was one of the first blues artist to make a name for himself in wider circles.

This information about Furry Lewis is from Wikipedia. Students can be encouraged to google this and other artists mentioned in this project.

After googling or being presented with some background information about the singer and the song, students now listen to the recording and follow the lyric on a handout. What they have to listen and look out for is what is taken over from the original newspaper report – now 30 years in the past –, what is added, and what is left out.

They will notice – among other things – that in Lewis’s version of the story the fight arises from a gambling dispute, that Billy Lyon’s sister pleads for her brother’s life but Lee shows no mercy, and that, because of Lee’s reputation as a killer, the sheriff, backed by his wife, is reluctant to go after Lee and bring him in “dead or alive”. They will also notice the insistent moralising refrain “When you lose your money, learn to lose”.

Early versions like this one tended to condemn Lee’s senseless, alcohol induced crime and offer the story as a moral warning. This was an example of how a man ought not to conduct himself. The relevance of this will become clear in the course of the project

Il. Guthrie

Il. Mississippi John Hurt

In 1928, white interest in the blues led to Mississippi John Hurt taking part in recording sessions in New York and Memphis, but then, with the depression of the 1930s, this interest in African-American popular culture became a luxury that had to be sacrificed and Hurt returned to working as a sharecropper for 35 years, until a folk musicologist named Tom Hoskins located him in 1963 and a performance at the Newport Folk Festival that year won him new recognition amongst the new folk revival audience. (Wikipedia.)

As a teenager Woody Guthrie, for his part, befriended an African-American blues harmonica player named "George” who awakened his interest in black musical folk culture. A comparison of the lyrics of the two songs [C] will show that Guthrie’s version is based on Mississipi John Hurt’s and there are many close parallels. Among them are these:

- “That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O' Lee” (Hurt) - “He was a bad man, that mean old Stagolee” (Guthrie)

- “Police officer, how can it be? You can 'rest everybody but cruel Stack O' Lee” (Hurt) - The high sheriff asked the deputy “How can it be? You can arrest everybody but you scare of Stagolee?” (Guthrie)

- “On Saturday we hanged him, we were all glad to see him die” (Hurt) - “At twelve o'clock they killed him, they's all glad to see him die” (Guthrie).

- "Gentleman's of the jury, what do you think of that? Stack O' Lee killed Billy de Lyon about a five-dollar Stetson hat" (Hurt) - Gentlemen of the jury what do you think about that? Stagolee killed Billy De Lyons about a five dollar Stetson hat. (Guthrie)

Il. Stetson

Again, asked to compare these new versions with the original report and Furry Lewis’s version of the events, students will be able to identify important new elements that have been taken up in the song. Lewis’s moralising refrain has given way to a kind of head-shaking stupour at the sheer evilness of Lee’s crime. The reluctance to go after the criminal, introduced by Lewis, is given more prominence by Hurt and Guthrie, but in these later versions he is brought to justice and hanged. The episode with the hat, that Lewis had ignored, is brought back as a key element in the story. In these new versions, it is Billy Lyons himself who vainly pleads for his life, thus emphasising Lee’s total lack of compassion.

To interpret the relevance of the new elements, students need to be provided with a wealth of cultural background material, which is available on the Jim Hauser Stagger Lee Files website, or could be provided in some other form, such as powerpoint, handouts, or via web quests. This background material is presented here in four blocks: The Bad Man Mythology, Taunting the White Authorities, Lee’s Death Sentence and Hanging, and the Symbolism of the Stetson Hat.

Whereas Furry Lewis provided an insistent moral warning as a refrain to his song, Hurt and Guthrie dwell on a head shaking repudiation of the evil – the cold-blooded callousness - of Lee’s crime.

On his website, Hauser explains how the story of Stagger Lee evolved in the early decades of the twentieth century as part of a tradition where folk tales about a legendary black bad man served the purpose of helping black people to bear the trials and torments of everyday white oppression. See:

www.geocities.com/blueskat2000/stagger_lee_mythic.html

The bad man of this tradition did not fight oppression; such a fight would have been doomed to failure. But he put himself beyond the morality and law of white society.

At this time, the morality and law of white society consisted of the twisted laws and customs of the Jim Crow system, a system of state and local laws enacted in the southern states of the USA and enforced between 1876 and 1965. They mandated “separate but equal” status for black Americans. The most important laws required that public schools, public places and public transportation have separate buildings, toilets, and restaurants for whites and blacks.

It was these laws that the African American had to abide by and which were defied by the badness of the legendary Stagger Lee. As such, the “bad man” Stagger Lee became a symbol of resistance to an unjust white authority for African-Americans.

Figures like Stagger Lee came to be admired in the black African-American community because they stood up to and defied the white man's system. Their badness put them – for a while at least – beyond the white man's law.

Thus, in Hurt’s and Guthrie’s versions, we find not only a reluctance on the part of the representative of white authority to risk his life going after the cold-blooded killer Lee, as was the case in Furry Lewis’s version, but a mocking of the police officer/deputy sheriff burdened with the dangerous task of bringing in the now legendary bad man. African-Americans felt a secret pride in the fact that “their” Stagger Lee was too much of a challenge for the enforcers of the white man’s law.

The personal resistance of the bad man was not a political victory, but it did mean refusing to resign oneself to the status quo and surviving with self-respect intact to fight another day.

James Baldwin said it to Maya Angelou: survival was a main ingredient which African-Americans put into their folk tales.

All this is to be found on Jim Hauser’s “Stagger Lee Files” website.

Lawrence Levine in his book “Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought From Slavery to Freedom”, quoted by Hauser, points out that the bad man of black folklore is in no way to be identified with the noble outlaw or social bandit, such as Robin Hood or Pretty Boy Floyd, in white folklore.

According to Levine, these benefactors to and heroes of the poor and oppressed are generated during times of great social change or upheaval and imply a desire for a return to a more legitimate order of the past (the just rule of Richard I or the intact farming family unit of pre-Depression Oklahoma).

This option was simply not available to the African-American community. For them, there was no idealised past which they could dream of restoring. Their roots had been severed. The “bad man” folk tradition among African Americans is probably a reflection of the fact that there was simply no possible vision of a better world and no tangible hope for change in the one they were condemned to live in.

There was no way out of the dilemma for the bad man except via the hangman’s noose. But it was a proudly defiant way out and, as such, the noblest option available.

www.geocities.com/blueskat2000/stagger_lee_stetsonhat.html

The Stetson was in the original newspaper report. It disappeared from Furry Lewis’s minimalist version of the story but is re-introduced in the Hurt/Guthrie versions.

The following information and interpretation is taken from Jim Hauser’s Files at the above URL address.

In his book “Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans”, Louis Armstrong tells how many black adult males coveted Stetson hats and often purchased them on instalment plans. Armstrong was born in poverty in New Orleans in 1901 and left for Chicago in the early 20s to pursue his burgeoning musical career.

In his doctoral dissertation, “Stagolee: From Shack Bully to Culture Hero”, Professor Cecil Brown explains how Stagger Lee's Stetson "represents his manhood." For many of the men who were now wearing Stetsons – around the turn of the century - were former slaves or sons of slaves. Now they were wearing them as free men on an equal footing with the white men who wore them.

The fight over the Stetson is not simply a dispute over stolen property. It represents a fight for manhood. The African American’s struggle for manhood was an element of the struggle for freedom and equality.

As Malcolm X argued: “the white man wants you to remain a boy." The $5 Stetson hat for which Stagger Lee shot Billy was ultimately a symbol of the black man’s manhood, his coming of age in white society. He was no longer “a nigger boy” but a free adult male. It was his manhood itself that Lee was recovering from Billy Lyons.

James Baldwin says that Rosa Parks helped Stagger Lee achieve his manhood.

Il. Baldwin

To make the leap from Stagger Lee to Rosa Parks we have to jump forward a quarter of a century. From the Depression of the early 1930s to the rise of the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s.

On the way, we will have to bypass a number of innovative renderings of the Lee legend, including that of white country singer, Tennessee Ernie Ford. This is an upbeat, tongue-in-cheek 1951 version of the story that contains all the essential ingredients, with the notable exception of taunting the white authorities, while adding the element of over-exaggerating the badness of Stagger Lee to such an extent that when he is hanged and goes to Hell, even the Devil is alarmed. This playful exaggeration of Lee’s badness became commonplace around the early 50s, suggesting that the serious intention behind the bad man mythology had lost much of its force.

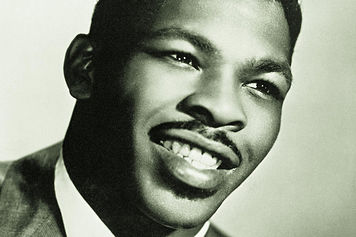

Il. Lloyd Price

When Lloyd Price’s version of Stagger Lee reached Number One in the U.S. charts in February 1959, it was the first rock ’n’ roll record by a black artist to do so.

Price had included the song in his repertoire as band leader in the U.S. Army while stationed in Korea in the mid-Fifties. The “Lee and Billy story” became a central pillar of his stage act. “While entertaining the troops, I put together a little play based on it. I'd have soldiers acting out the story while I sang it". After discharge from the army, Lloyd returned to his recording career and included a version of his Stag Lee army act as the B-side of his 1958 single "You Need Love". When deejays discovered it and started to air it in preference to the A-side, it became, as they say, an overnight sensation.

Lloyd Price’s rock’n’roll version broke with the old Stagger Lee tradition.

This break with the tradition can be directly linked to Rosa Parks, who, according to Baldwin, remember, helped Stagger Lee to achieve his manhood.

On December 1, 1955, going home from work, Rosa refused to give up her seat to a white man and move to the back of the bus, which the Jim Crow segregation laws still demanded. On the face of it, this was an act of wilful "badness" in line with the bad hero of the folk tradition. It was a refusal to resign to the status quo, surviving to fight another day.

Only Rosa Park’s individual act of resistance must be seen in the context of a burgeoning civil rights movement that she was in contact with and that gave moral support to her actions.

Barely two years later, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1957, the first major piece of civil rights legislation passed in over 80 years. In September 1957, federal troops guarded black students bringing about the court-ordered integration of a high school in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Rosa Park’s defiance led to the Montgomery bus boycott and had political repercussions which changed the face of race relations in the U.S.A.

Against this background, Lloyd Price’s army stage act of “Stagger Lee” was evolving in Korea. In Korea, U.S. troops had been racially integrated since 1950, one of the very first signs of the breaking down the walls of segregation. Having grown up in the South, Price must have appreciated and been positively affected by this. These events and experiences went into the development and would find expression in the final version of the song.

Il. Rosa Parks 1

Il. Rosa Parks 2

After this introduction, let’s listen to the song and read the lyric [D]. Hauser points it out and there is no denying it. Lloyd Price’s version of Stagger Lee sounds unmistakeably like a celebration: the rocking, rampant exuberance of its delivery and the exhilaration of its whooping and rallying choruses. The upbeat tone and aggressive attitude are absent in all earlier African-American versions of the song. Price's “manic enthusiasm” is a major element missing in any previous recording of the song.

Says Hauser: “Stagger Lee: From Mythic Blues Ballad to Ultimate Rock 'n' Roll Record” (www.geocities.com/blueskat2000/stagger_lee_mythic.html).

Hauser draws parallels between the jubilant tone of Price's “Stagger Lee” and certain slave spirituals of the previous century, in particular “In That Great Gettin' Up Morning”, which reached great popularity in the mid-nineteenth century at a time when the slaves foresaw that their freedom was at last close at hand. As such gospels were songs of celebrations anticipating the imminent release from slavery, so may “Stagger Lee” be seen as an anticipatory celebration of the attainment of equal rights. When Price recorded "Stagger Lee" in late 1958, African-Americans must have had a similar anticipation of victory in the civil rights struggle.

In contrast to early versions of the story, there is no moralising in Price’s song. There is sympathy for the victim (poor boy) but no head shaking condemnation of the villain. Furthermore, Price’s version ends at the moment of the shooting. In nearly all previous recordings, from Mississippi John Hurt’s 1928 version on, Stagger Lee is arrested, brought to justice, and duly executed.

Maybe one of the most surprising features of the 1958 version, says Hauser, is the way the backup singers, in the course of the narration, seem to be urging the killer on, with their insistent and inciting chant "Go Stagger Lee", given greater urgency by the insistent rise of an octave on the fourth and last bar.

Charlie Gillett in his rock history “The Sound of the City”, points out that Price's record company, ABC-Paramount always tended to provide a loud, rhythmic, and cheerful musical backing for his voice on all Price's records. So it seems questionable whether there is any deliberate ideological intention here. Nonetheless, this dissonance between the cheerful arrangement and the brutal story-line is what makes this recording unique and in a way it speaks for itself.

The Hidden Message in Lloyd Price's "Stagger Lee"

www.geocities.com/blueskat2000/stagger_lee_joshua.html

Besides, in addition to this new spirit of defiance in the 1958 version of the song, there is a subversive ideological underpinning of Stagger Lee’s action to be found in the extraordinary and innovative, suspense-creating two-line introduction to the story:

The night was clear and the moon was yellow…

… And the leaves came tumbling down

Then “seven quick horn blasts shatter the calm” (Hauser). This arrangement evokes a slave spiritual, frequently sung in church by black congregations and which Price must have known, entitled "Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho" – not only in that the line "and the leaves came tumbling down" echoes the spiritual's line "and the walls came tumbling down", but those seven horn blasts also echo the sounding of trumpets as the biblical battle commences.

Thus, the seven quick horn blasts in the introduction to the song echo the seven trumpets of rams' horns that were blown by seven priests after circling the city seven times on the seventh day of the siege of Jericho in the bible story.

And in the song, the back-up singers shout as they join in with later sets of horn blasts, also paralleling the bible story in which the people who were gathered around Jericho shouted after hearing the trumpet blasts – in a form of psychological warfare.

Incidentally, for number fetishists, seven was the number Stagger Lee threw and the name Stagger Lee is mentioned seven times in the fourteen lines of the song.

To African-Americans, "Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho" had long had a special significance in that this battle was seen as symbolic of the fight to end slavery. Joshua was the God-chosen successor of Moses who was to lead the people of Israel into the land that He had promised them in the time of their forefathers (Deuteronomy 31.7).

Joshua represented the black man in his righteousness, his faith in God, and his perseverance against heavy odds. As God had intervened on behalf of Joshua, as He had intervened on behalf of the slave population, so would He intervene again in the just struggle for equal rights in the U.S. South. With the inevitability of the falling leaves, like the walls of Jericho, the walls of segregation would come tumbling down.

In Price's version, then, Stagger Lee is no longer presented as a bad man, boldly but vainly defying white authority. Rather, he is a man seeking justice who has, if not God, then at least Right on his side. According to the lyrics, as Hauser points out, that Stagger Lee threw seven is a fact, but in swearing that he threw eight, Billy is shown to be a cheat.

Price makes it clear that Stagger Lee lost to a cheat and is presented as a man who was swindled and then exacted justice by taking the law into his own hands: a form of ghetto or street justice, - indeed, the very kind of justice that earlier blues versions moralised against.

Thus, "Stagger Lee" was reshaped from the cautionary blues ballad that we saw in Furry Lewis’s 1927 version to an aggressive rock 'n' roll song in the late 50s. In effect, Price created a new song with a new symbolic meaning. By taking "Stagger Lee" out of the old blues and folk tradition and re-working it as rock 'n' roll, he changed its theme from surviving oppression to active self-liberation. With Price’s 1959 version of Stagger Lee, the African American has finally achieved his manhood.

Il. Lewis

Ask students, at the end or along the way, to fill in this schematic representation of the essential ingredients of the Stagger Lee legend as it evolved during the twentieth century.

| Elements included in the song |

1927 |

1928 |

1931 |

1951 |

1958 |

? |

| fight over a gambling dispute |

√ |

x |

x |

√ |

√ |

|

| The Stetson hat |

x |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

| Billy cheated |

x |

x |

x |

√ |

√ |

|

| Billy (or wife or sister)pleaded for his life |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

| Cold blooded murder; no mercy |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

| Stag tried and sentenced to death |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

x |

|

| Stag hung (Justice is done) |

x |

√ |

√ |

√ |

x |

|

| Worse than the Devil |

x |

x |

x |

√ |

x |

|

| Taunting White authorities; can’t catch him |

√ |

√ |

√ |

x |

x |

|

| A bad man (moral condemnation) |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

x |

|

| Leaves came tumbling down prelude |

x |

x |

x |

x |

√ |

|

[1927: Lewis; 1928: Hurt; 1931: Guthrie; 1951: Ford (omitted here for reasons of space); 1958: Price; ?: your chosen version.]

There are many other outstanding versions of the Stagger Lee legend recorded before and after Lloyd Price’s rock’n’roll version. Many of them are listed by Hauser here: www.geocities.com/blueskat2000/stagger_lee_recordings.html

An even more comprehensive list including a brief description of each version is to be found on the music blog « Largehearted Boy » : http://www.Largehearted Boy Book Notes - Derek McCulloch (Stagger Lee).htm. Here Derek McCullough, the author of a graphic novel about the legendary killer, describes how 36 different musical versions of the tale provided inspiration for both himself and his illustrator, Shepherd Hendrix.

A few of the most notable recordings mentioned by McCullough are

- Archibald’s 1950 “landmark in the history of Stagger Lee”, drawing from many different versions of the story and shaping it all together in a single coherent narrative, culminating in the final triumph of evil Stack-a-Lee (he kicks the devil off his throne and claims the place for himself). It was too big a story to fit on one side of a single, so Archibald split it into two parts.

- Bob Dylan’s 1993 cover of Frank Hutchison’s 1927 recording,

- “Wrong ‘Em Boyo”, The Clash’s cover of a 1967 version by a reggae band called “The Rulers” on their 1979 album “London Calling”. This version reverts to a moral appeal to do the right thing, with Stagger Lee as a negative moral example.

- Nick Cave’s 1994 foul mouthed rendering of a “prison toast”, a precursor genre of rap.

36 different versions are commented on by McCullough, but well over 200 have been listed elsewhere. Students could be asked to search for and research one of these versions and present it to the class. And to place it on the “essential elements” chart.

For a Bibliography of works referred to:

www.geocities.com/blueskat2000/stagger_lee_biblio.html

And thanks, once again, to Jim Hauser for his inspired and inspirational website: The AKA Blues Connection's Stagger Lee Files: http://www.geocities.com/blueskat2000/stagger_lee_home.htm

A

From the December 28, 1895 edition of the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat.

Shot in Curtis's Place

William Lyons, 25, colored, a levee hand, living at 1410 Morgan Street, was shot in the abdomen yesterday evening at 10 o'clock in the saloon of Bill Curtis, at Eleventh and Morgan Streets. by Lee Sheldon, also colored. Both parties, it seems, had been drinking and were feeling in exuberant spirits. Lyons and Sheldon were friends and were talking together. The discussion drifted to politics and an argument was started, the conclusion of which was that Lyons snatched Sheldon's hat from his head. The latter indignantly demanded its return. Lyons refused, and Sheldon drew his revolver and shot Lyons in the abdomen. Lyons was taken to the Dispensary, where his wounds were pronounced serious. He was removed to the city hospital. At the time of the shooting, the saloon was crowded with negroes. Sheldon is a carriage driver and lives at North Twelfth Street. When his victim fell to the floor Sheldon took his hat from the hand of the wounded man and coolly walked away. He was subsequently arrested and locked up at the Chestnut Street Station. Sheldon is also known as "Stag" Lee.

www.geocities.com/blueskat2000/stagger_lee_home.htm

Addendum:

Billy Lyons died from his wounds, and Lee was tried for his killing. He was finally convicted, served time, and died in the nineteen-tens (in prison, or after his release?).

B

From the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat report.

True or False?

- Billy Lyons and Stag Lee got into a fight over a gambling dispute.

- In the fight, Billy grabbed Stag Lee’s Stetson hat of his head.

- Billy pleaded for his life.

- Lee shot Billy Lyons in cold blood.

- It seems Stag shot Billy to retrieve his Stetson hat.

- Stag was tried and sentenced for his crime.

- Stag was hung for the murder of Billy Lyons.

1: F (although a gambling dispute quickly became an integral part of the legend). 2: T (apparently trivial, but an important part of the story as it evolved). 3: F (though pleading for his life to emphasise Lee’s callousness became an essential part of the legend). 4: T (essential to the story). 5: T (essential). 6: T. 7: F (Lee served a lengthy prison sentence).

C

MISSISSIPPI JOHN HURT. 1928 VERSION

Stack O'Lee Blues

Police officer, how can it be?

You can 'rest everybody but cruel Stack O' Lee

That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O' Lee

Billy de Lyon told Stack O' Lee, "Please don't take my life,

I got two little babies, and a darlin' lovin' wife"

That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O' Lee

"What I care about you little babies, your darlin' lovin' wife?

You done stole my Stetson hat, I'm bound to take your life"

That bad man, cruel Stack O' Lee

...with the forty-four

When I spied Billy de Lyon, he was lyin' down on the floor

That bad man, oh cruel Stack O' Lee

"Gentleman's of the jury, what do you think of that?

Stack O' Lee killed Billy de Lyon about a five-dollar Stetson hat"

That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O' Lee

And all they gathered, hands way up high,

at twelve o'clock they killed him, they's all glad to see him die

That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O' Lee

[ Lyrics found at www.mp3lyrics.org/97cV ]

WOODY GUTHRIE. 1931 VERSION STACKOLEE

Stagolee was a bad man, ev'rybody knows.

Spent one hundred dollars just to buy him a suit of clothes.

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee

Stagolee loaded cotton weighed five-hundred pounds,

Carried along a Gatlin gun drug him to the ground.

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

It was in a hustling “B” joint where the Mississipi run

Stagolee killed Billy De Lyons with a smoky forty-one.

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

Gentlemen of the jury what do you think about that?

Stagolee killed Billy De Lyons about a five dollar Stetson hat.

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

Billy de Lyons said, Stagolee please don't take my life

I've got two little babes and a darling, loving wife;

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

What do I care about your two little babes, your darling loving wife?,

You done stole my Stetson hat I'm bound to take your life;

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

Billy was in the courthouse a-kneeling on the floor

Stagolee pulled the trigger of his red hot forty-four.

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

The high sheriff asked the deputy “How can it be?

You can arrest everybody but you scare of Stagolee?”

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

The deputy told the new sheriff ,”Well, double up my fee

I’ll go get that outlaw by the name of Stagolee.”

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

Billy died in the sawdust with his head upon the rail

Deputy took old Stagolee and he marched him off to jail.

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

The judge said, Stagolee,”Mister Stagolee,

I’m gonna hang your body up and set you spirit free.”

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

Stagolee on the gallus his head way up high

Last thing that poor boy said,"My six-shooter never lied."

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee.

Twelve o’ clock they killed him, his head reached up high

On Saturday we hanged him, we were all glad to see him die.

He was a bad man that mean old Stagolee

[From: Paroles Stackolee (Stagger Lee) - Woody Guthrie – www.MusiqueAdos_fr.htm]

D

LLOYD PRICE. STAGGER LEE LYRIC: 1958

The night was clear and the moon was yellow

And the leaves came tumbling down

I was standing on the corner when I heard my bulldog bark

He was barkin' at the two men who were gamblin' in the dark

It was Stagger Lee and Billy, two men who gambled late

Stagger Lee threw seven, Billy swore that he threw eight

Stagger Lee told Billy, "I can't let you go with that"

"You have won all my money and my brand new stetson hat"

Stagger Lee started off goin' down that railroad track

He said "I can't get you Billy but don't be here when I come back"

Stagger Lee went home and he got his forty-four

Said "I'm goin' to the barroom just to pay that debt I owe"

Stagger Lee went to the barroom and he stood across the barroom door

He said "Nobody move" and he pulled his forty-four

Stagger Lee shot Billy, oh he shot that poor boy so bad

Till the bullet came through Billy and it broke the bartender's glass

[copied from: www.bobshannon.com/stories/Stagger.html]

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|