Drama and language teaching: the relevance of Wittgenstein's concept of language games

Mike Fleming

Mike Fleming is Director of Research at the School of Education, Durham University, England. He has written several books and many articles on the teaching of drama.

E-mail: m.p.fleming@durham.ac.uk

Menu

Introduction

Context and language games

Drama approaches

Brief history of drama teaching

Drama examples

The paradox of drama

Introduction

There are many reasons in favour of using drama as a pedagogic technique in the language classroom. It is fun and entertaining and can therefore provide motivation to learn. It can provide varied opportunities for different uses of language and because it engages feelings it can provide a rich experience of language for the participants. Drama is inevitably learner-centred because it can only operate through active cooperation. It is therefore a social activity and thus embodies much of the theory that has emphasised the social and communal, as opposed to the purely individual, aspects of learning. This article offers some practical suggestions for using drama after a discussion of how Wittgenstein's notion of language games can provide further theoretical insight into the value of drama for language learning.

Context and language games

With regard to the learning of language, the value of drama is often attributed to the fact that it allows the creation of contexts for different language uses. In both language teaching and drama, context is often thought to be everything. There is a long tradition, influenced by sociolinguistics, from a conception of language learning as the acquisition of vocabulary and grammar independent of context to a greater focus on language in use. However the word 'context' itself can vary in meaning depending on use. Wittgenstein (1958) makes an interesting distinction in The Brown Book between 'context' and 'language game'. He introduces this distinction in a discussion of how our understanding of the concept of time can be obscured by assumptions about language. When we try to explain how a word like 'now' or 'is' functions this can only happen if we look at the role this word really plays in our usage of language. He goes on to say that our understanding is obscured 'when instead of looking at the whole language game we only look at the context, the phrases of language in which the word is used.' When we say 'the sun sets at six o'clock' and 'the sun is setting now' the similar form makes us think that 'now' is functioning in the same way as 'six o'clock' and this causes all sort of difficulties. There are parallels here with Wittgenstein's distinction between deep and surface grammar. The surface grammar of 'I have a pain' is the same as 'I have a pin' but unless we realise the different language games going on, all sort of philosophical difficulties arise (Wittgenstein, 1953: 168).

He uses the term 'context' to refer to the way words can be explained in relation to their function in specific uses of language e.g. in particular sentences. His own explanation for his preference for 'language game' is that the term 'is meant to bring into prominence the fact that speaking of language is part of an activity, or of a form of life' (Wittgenstein, 1953:11). The reference to 'form of life' draws attention to the fact that language has meaning by virtue of the fact that it is embedded in a wide cultural context. This view is in contrast to the idea of language meaning as a form of 'calculus', a system that is 'governed by formally defined rules' (Stern, 2004:90). It is important not to make too much of the difference between 'context' and 'language game' here. To some commentators, the concept of language games simply serves to emphasize the importance of taking context into account when trying to understand or explain the meaning of linguistic expressions (Schulte, 1992:101). We might just as well be referring to different types of context as make the distinction between the two terms. What is important is the distinction between what might be termed 'thin' and 'rich' explanations of language use; I will use the terms 'context' and 'language games' to capture that difference.

Language teaching has come a long way since it relied almost exclusively on de-contextualised routine exercises. Traditionally a sentence such as 'Tomorrow I will go to the department store and buy a large teddy bear' would exist in the language classroom simply to illustrate the use of tenses and adjectives. Communicative approaches place language more in contexts but sometimes these are artificial, mechanical and shallow. We imagine, for example, that this sentence is spoken by a parent to a child but that is as far as it goes because there is now a (thin) context to explain the way the sentence functions. However a focus on deeper meaning prompted by a dramatic reconstruction prompts a number of questions about the sentence: not just 'who is speaking and to whom?' but questions such as 'why is he/she buying a teddy bear? is there any significance in the fact that it is a large teddy bear?' Drama goes even further and allows the participant to become or to talk to the person who has declared their intention to buy a teddy bear. Drama invites participation in the possible 'language games' in which the sentence might be embedded. Is this a mother trying to calm her child, a father being sarcastic, a teenager planning a first date, an estranged husband going to see his child for the first time in months, a smuggler planning how to get drugs through the customs? The creation of a richer context in order to bring the utterance to life in a drama raises questions about tone. Is the sentence spoken in a light-hearted, sarcastic, defiant or angry moment? Perhaps the line was spoken in prison at the end of a conversation between husband and wife. When we look at the sentence again it seems rather formal and deliberate (for example. the use of 'I will' instead of I'll) which may restrict the possible situations in which it was uttered. This is a very simple example but it illustrates the way drama can bring language to life.

Taylor (199:63) has commented that, despite its considerable influence in philosophy of language, Wittgenstein's work has had less influence on linguists than might be expected. Taylor explains this by stating that the priority given to understanding and explanation over the notion of meaning in his work was in contrast to the semantic tradition in linguistic theory which focuses on the relation between meaning and form. This is another way of approaching the distinction between 'context' and 'language game'. A traditional view of successful communication is to say that the hearer receives the speaker's meaning, that when people understand each other there must be something identical in each other's minds. But the Wittgenstein view sees understanding as something which happens 'on the outside', so to speak, between not within people (hence the emphasis on language games). The Wittgenstein approach recognises that meaning arises through use, through agreements in culture or 'forms of life' and not just by attaching names to objects or phenomena in the world or by transferring 'meanings' from one mind to another. The idea that understanding of language takes place in a form of life is in total contrast to the idea of language simply as a system of signs. It emphasises instead that language is embedded in the significant behaviour (including non-linguistic behaviour) of human beings. That does not mean that grammatical structures are not important - but the bedrock of meaning is in its use. This is why drama can be such a useful pedagogic tool.

Drama approaches

Drama techniques have had a long history in language teaching in the form of exercises, games and simulations (acting out make-believe scenarios in order to practise different uses of language) (Butterfield, 1993; Dougill, 1987; Maley and Duff, 1978). The possible categories of drama forms in language learning can be described as follows (Fleming, 2000):

Typical exercises/warm-ups/games might take the following form: in pairs students stand back to back and try to recall as much as they can about each other's appearance; everyone tries to shake hands and greet as many people as possible in the group; in small groups the class try to act out a scene which represents a time of day and the class try to guess in the target language what time is being represented.

Improvised role play might involve the class dividing into pairs to act out a spontaneous exchange between shopkeeper and customer. Scripted role play is based on similar situations with the dialogue written out for the participants in advance. As a variation, learners are not given access to each other's lines until the dialogue is enacted.

More extended drama simulations might involve students in creating individual fictitious characters in a specific context (e.g. people living in the same country or village who speak and write to each other over a period of time).

These examples place language in 'context' but drama approaches which pay greater attention to the art form of drama, by seeking for example to inject tension into enacted situations, embody more of the 'language games' which attach to human communication. For example, instead of a simple scenario of buying an article in a shop, the teacher might set up a richer context in which the two participants knew each other at school and were great rivals. It is this way that drama techniques can be used to explore thoughts and feelings.

Despite its rich potential, drama as a classroom method brings a number of challenges for the teacher. It involves moving away from familiar structures and routines which feel safe into approaches which are more open-ended and unpredictable. With younger learners the enthusiasm and exuberance produced by engaging in drama can turn into problems of discipline. With older learners there may be problems of inhibition and embarrassment. Despite the enormous potential for drama to motivate and engage the participants, in practice the drama can sometimes be flat and fail to inspire. In the context of teaching a second language, the possibilities are inevitably limited by the fluency and language facility of the learners. These comments are not meant to be negative but to offer a realistic view of the challenges involved in using drama in the language classroom.

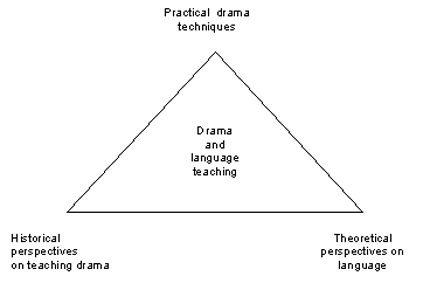

This paper will describe some techniques for using drama in the language classroom bearing in mind both these practical challenges and the theoretical perspectives on language. For readers who are new to drama, the techniques may offer some fresh ideas for use in the language classroom. For others for whom the techniques may be familiar, the intention is to provide a fuller explanation of the rationale for their use in terms of perspectives on language and in terms of the practical challenges in the classroom. Before examining some of these methods, however, it will be helpful to provide some brief background on historical approaches to drama teaching because these can provide an explanation of how misunderstandings of the nature of drama can lead to problems in the classroom. For example, language text books often carry the recommendation at the end of a unit or theme that learners should 'do some drama' or 'role play' almost as an afterthought, with the assumption that it really is that easy and does not require any further thought or structure on the teacher's part. It is intended that the different perspectives offered here will converge to inform thinking about the use of drama in the language classroom.

Brief history of drama teaching

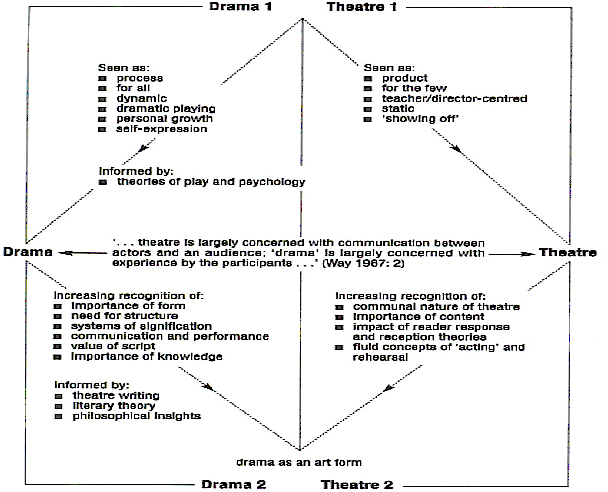

Traditionally 'theatre' has been taken to refer to performance whereas 'drama' has referred to the work designed for stage representation, the body of written plays (Elam, 1980). In the context of drama teaching however the terms have been used differently. 'Theatre' was thought to be largely concerned with communication between actors and an audience; whereas 'drama' was largely concerned with experience by the participants, irrespective of any function of communication to an audience (Way, 1967). In the 1980s and 1990s in England and many other countries there was a fairly pronounced division between writers and practitioners who advocated different approaches to teaching drama. Teachers who took a theatre approach talked about 'acting', 'rehearsal' and 'performance' whereas teachers with a drama focus referred more to 'experience' or 'living through' improvisations (Hornbrook, 1989). In practice these tended to be more orientations in the work rather than rigid distinctions but the differences are crucial in understanding the way drama teaching developed; legacies of these approaches are found in contemporary practice.

The method of drama teaching which developed from the 1950s onwards which embraced more free forms of dramatic play and improvisation can be seen as a reaction to the stifling and uncreative approaches at the time which involved children acting out in a rather formal way the words of others rather than developing ideas of their own (Slade, 1954). The suggestion was that when participants are engaged in more spontaneous, improvised work (traditionally called 'drama') their level of engagement and feeling will be more intense and 'genuine' than when they are performing on stage (traditionally called 'theatre'). The theoretical perspectives on drama education were at that time drawn from writings on child play and psychology rather than on the theatre. The emphasis was on the personal growth of the individual through creative self expression and the influence of progressive educational theorists was also apparent. In Emile Rousseau had advocated a form of education based as far as possible on nature with minimal interference from adults. Similarly the early advocates of drama in education assumed that all children have the propensity to engage in dramatic play and based their approaches on the minimal intervention of the teacher. This idea that it is enough just to tell pupils to 'do some drama' or 'make up a play' which was identified earlier as being common in many language books has its origins in the early perspectives on teaching drama.

The recent history of drama teaching being described here is represented in the diagram (Fleming, 2003). At the time when the separation of 'drama' and 'theatre' was happening what was being rejected was the negative aspects of theatre practice (depicted in the upper right side of the diagram) when imposed prematurely on young people. A more contemporary view of theatre practice is represented in the lower right quadrant (Theatre 2). Here the approach is less authoritarian, there is a more fluid concept of what 'acting' and 'rehearsal' involve and there is greater acceptance of non -naturalistic approaches. Similarly there has been a change in the way drama has been conceptualised. The changed conception at Drama 2 in the diagram means that all drama in the classroom can draw on insights provided by the nature of drama as art and writings from theatre practitioners (Bolton, 1992; Heathcote, 1980; Shewe and Shaw, 1993).

How does this brief account of past division in the drama teaching world inform the practicalities of using drama in the language classroom?

- The traditional view of theatre represented in the diagram as 'Theatre 1' is a reminder that some approaches to drama can be static and lack the kind of creative dynamism that the participants often expect.

- It provides a reminder that drama requires structuring and that drama techniques need to be learned by the participants, It is no longer appropriate to see drama entirely as a natural activity which needs little intervention from the teacher.

- Drama approaches can blend elements traditionally associated with 'drama' and 'theatre', including elements of performance, as long as the teacher is sensitive to learners' potential embarrassment.

- The use of drama does not have to involve the development of a complex narrative as was often assumed when drama is seen as 'dramatic playing'. This is helpful to the teacher of language because an approach which slows down the onward rush of plot is also helpful to the language learner.

- The preoccupation with naturalism or getting the drama to imitate reality can be counter-productive. This again is helpful to the language learner because many of the non-naturalistic techniques such as tableaux described below simplify the uses of language.

Drama examples

The aim in this section is to provide some practical approaches to using drama. These will be presented in the context of an explanation as to why an understanding in both the context of drama as an art form and in the context of theoretical perspectives on language and meaning can converge in assisting teachers choose appropriate pedagogical methods. The practical examples will centre on the use of the story of the Pied Piper captured in Browning's poem. The work is well known but it might be helpful to give a brief reminder of the story on which it is based. A city is so plagued with rats that the townspeople complain to the mayor. The Pied Piper is promised payment if he rids the town of the rats, which he does successfully by playing his musical pipe. When he is refused the promised payment his revenge is to charm the children of the town away with his music. They all follow him to a gap in the mountainside through which they disappear. One lame boy who cannot keep up is left behind. The choice of narrative is not important for the methods can be transferred to other texts. I have written before about the Pied Piper as a stimulus for drama using similar techniques but the suggestions are offered here with more focus on language (Fleming, 2003).

It is perhaps worth pointing out that the use of drama is seen here as a complement to other approaches in the language classroom not as an attempt to replace them. It would be na´ve to imply that there is no place for formal instruction and reinforcement through practise and drill. In fact, as will be seen, some of the drama approaches described here can function as a form of repetitive drill without making the language uses superficial.

Freezing a moment in time

A tableau or 'freeze-frame' is one of the most common techniques used in the drama classroom. It involves participants creating and holding a still image with their bodies to capture a particular dramatic moment. Why should an activity that does not primarily involve speaking be a useful stimulus in the language classroom? There are practical pedagogical reasons: because the activity results in a still moment of silence and slows down the onward flow of plot characteristic of dramatic playing, it avoids the chaos that sometimes attends first forays into drama and it thus acts as a useful introduction to its use. From a language perspective the technique encourages learners to think about the ways in which meaning can be condensed and focused into single sentences or phrases. By asking groups to translate language into a concrete alternative form they need to look beyond the surface meaning of the words.

With the Pied Piper story the participants can be given one or two lines from the poem and asked to create a tableau in groups which represents the lines while reading the short extract aloud. If groups are given the same lines, the different interpretations can be compared and the learners become highly familiar with the chosen lines through repeated examination of them.

A suitable line might be

'Come in' - the mayor cried, looking bigger

And in did come the strangest figure

By giving the participants different lines the language demands can be increased. With more advanced learners the technique can be used as a comprehension activity ('create a tableau which best sums up this passage'). It can also be used with the lines from the script of a play ('create a tableau which shows where the actors would be standing at this precise moment in the play'). An additional way of enriching the activity is to asking the participants to articulate the thoughts of individual characters. This is using language in a fairly accessible way but the utterances are likely to be loaded with emotional content, e.g. the thoughts of the mayor when he realises his actions have caused the loss of the children; the thoughts of the parents whose children have gone missing.

Asking questions

The technique of questioning in role whereby a fictitious character is asked questions by the rest of the group is also useful for beginners in drama (whether teacher or class) because it is controlled and focused. However it allows characters' intentions and motivations to be probed in ways which can be highly charged and emotionally tense. For example the mayor of Hamelin can be asked questions about his reactions and feelings when he learned that it was his failure to the pay the Piper that caused the loss of the children. Parents can be interviewed to determine their reactions. The children who were taken away by the Pied Piper can be questioned about their life away from Hamelin. With learners who are less fluent in the language, the teacher can adopt the different roles, allowing the learners to concentrate on the questions. In this case there is an element of practice and drill in the formation of questions, in conjunction with the desire to probe characters' motivations.

Pairs work

One of the characteristics that distinguishes the use of drama as an art form from simple role play situations is the injection of extra layers of complexity and depth. As suggested earlier in this paper, the terms 'context' and 'language game' are being used to refer to the respective 'thin' and 'rich' uses of language. The process of injecting depth does not necessarily need elaborate structures or complex forms of language; it is rather a process of endowing simple uses of language with more depth. There are a number of situations which can be acted out in pairs related to the story: two neighbours who both have a problem with rats meet, but at first they are embarrassed to admit this to each other; a citizen complains to the mayor and feels from the responses received that the problem is not being taken seriously; the Pied Piper returns for his money and is not satisfied with the answer he receives. The actual exchange of words does not have to be complex and can be adapted from the words of the poem as, for example, when the mayor claims that the contract was a joke and refuses to pay what was promised (the thousand guilders):

"But, as for the guilders, what we spoke

Of them, as you very well know, was in joke.

Besides our losses have made us thrifty;

A thousand guilders! Come, take fifty!'

Using script>

Of course these situations require a degree of fluency with the language and the use of short lines of script can be useful with learners who are less confident or competent. As described above, at one time the use of script was dismissed as being an uncreative and somewhat mindless activity. However this is not the case if emphasis is placed on interpretation of nuance and sub-text. The sequence of words can remain the same but they can be actualised in different ways. Here for example is a simple exchange between members of the town council after the Piper has taken the rats away.

How much did he ask for?

Ten thousand

Did he really?

Yes he did.

The whole immediate course of events when the councillors refuse to pay the money promised and the Piper takes revenge, could be said to hinge on that one phrase 'did he really?' - or not, depending on how it was meant and interpreted. The three lines can be enacted in different ways to show different interpretations of the underlying sub-text. Is the phrase 'did he really?' loaded with the implication that this is too much to pay? This can be followed by the writing and representation of further lines of script extending the exchange. Perhaps it is actually the way the line 'Yes he did' is delivered that actually suggests that paying up is not necessarily the only course of action that is possible.

Another approach is to take a few lines of script and insert the actual sub-text or unspoken thoughts which can then be delivered by two other participants in the course of the exchange, as in the example below. Notice that the questions here actually function pragmatically as statements.

Do you think the Piper expects us to pay the full 10,000? (He must think we are fools).

Is he rich? (He will be satisfied with a smaller amount of money).

Does anyone know where he is from? (We are not going to give all that money to stranger).

He seemed a very nice person. (If we don't pay him he won't do anything).

He might like a thank you letter. (We are definitely not going to pay him).

Small group work

More advanced learners can be asked to create small group presentations as long as these are carefully introduced. The imaginary situation is that it is now many months since the children were taken away by the Pied Piper. The class are asked in groups to prepare, rehearse and present a short scene which shows a town bereft of its children. The scenes can simple and understated - for example, shops no longer sell sweets, the swings are being taken down in the park, a family look through their photograph album. The groups are given a definite (single) space in which to work and are restricted to a number of lines.

Oblique approach

Another method is take an oblique approach to the story. For example a group of investigators arrive at the town to investigate the disappearance of the children and conduct a series of interviews with the townspeople to establish what has happened.

This is not a straightforward procedure because the townspeople are keen to conceal their part in causing what happened by breaking their promise to the Piper. The activity can take place in pairs or groups. The language demands are not great but the exchanges can carry resonance beyond the surface meanings. Typical questions might take the following form.

How many children do you have?v

What ages are they?

What were you doing when they went missing?

Is there any connection between that and the problem you had with rats?

Pied Piper themes

The Pied Piper is usually seen as a children's story but its themes which can be explored through drama are wide-ranging and searching. For example it raises question related to

- the consequences of breaking a promise

-making moral judgements: who was most at fault - the mayor or the Pied Piper?

- ensuring that citizens' rights are respected

- examining corruption among town officials

- exploring people's capacity for self-deception

- the nature of life: have the pupils passed through to a better world?

The final theme is embodied in the reactions of the lame child who is left behind.

'I can't forget that I am bereft

Of all the pleasant sights they see,

Which the Piper also promised me,

For he led us, he said, to a joyous landů

And just as I became assured

My lame foot would be speedily cured

The music stopped and I stood still,

And found myself outside the Hill.'

There is an ambiguity here. The children have been captured and taken away from their families but the implication is that they may have gone to a more 'joyous land'.

The paradox of drama

At the start of this paper I appropriated the Wittgenstein term 'language game' to highlight the potential of drama to create rich contexts for language use. Finch (1995:46) has pointed out that Wittgenstein used the phrase ambiguously, both to highlight different uses of language but also to refer to language itself as a whole:

'I shall also call the whole, consisting of language and the actions into which it is woven, the language-game' (Wittgenstein, 1953: 7).

So far we have looked at different uses of language within drama. When we think of the 'whole' within which the use of language takes place, an interesting and useful paradox becomes apparent. At the heart of the 'total language game' which is the creation of the drama is the key element of fiction or make-believe. As has been argued, one of the values of drama is that it allows the creation of rich contexts that embody tension and feeling. However the creation of a fictional context paradoxically simplifies the situation in order to examine human motivation and intention more explicitly. On the surface, the dramatic representation seems to replicate reality particularly if it is using naturalistic conventions; however the characters who exist in the drama occupy the narrower more confined fictional world which is created.

Clearly we bring our experiences from life to understanding drama but there is a sense in which the drama creates its own reality which allows an exploration of complexity because of its simplification. Theatre (and drama) 'is that one place where society collects in order to look in upon itself as a third-personal other.' (States, 1987:39)

As I have argued elsewhere (Fleming, 2003b) drama operates through a series of paradoxes. It allows participants:

- to be emotionally engaged yet distant (it is easy to become emotionally engaged while knowing that the situation is purely fictional);

=- be serious yet free from responsibility (the participants in the drama have to face up to the consequences of their actions but the fictitious context frees the them from any real responsibility);

- be participant as well as observer (one can actively engage in drama while at the same time keep one's actions under review);

- be open to the new while rooted in the familiar (participants bring to the fictitious context their real life experiences but the quest to create something new takes them to the creation of new meanings captured within the symbolic action of the drama);

- simplify situations in order to explore their complex depths.

References

Bolton, G. (1992) Perspectives on Classroom Drama. Hertfordshire: Simon and Schuster.

Butterfield, A. (1993) Drama through language through drama, Banbury: Kemble

Dougill, J. (1987) Drama activities for Language Learning. London: Macmillan.

Elam, K. (1980) The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. London: Methuen. Reprinted in 1988 by Routledge.

Fleming, M. (2000) 'Drama' in Byram. M. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Language Teaching and Learning. London Routledge.

Fleming, M. (2003) Starting Drama Teaching. London: David Fulton Publishers

Fleming, M. (2003b) 'Intercultural Experience and Drama' in Alred, G, Byram. M. and Fleming, M. (eds.) (2003) Interultural Experience and Education. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Heathcote, 1980 Drama as Context NATE papers in education: London; NATE

Hornbrook, D. (1989) Education and Dramatic Art. London: Blackwell Education.

Maley, A. and Duff, A. (1978) Drama Techniques in Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted in 1982.

Rousseau, J. (1911) Emile. London: Dent. Translated by Barbara Faxley, Reprinted 1961.

Schulte, J. (1992) Wittgenstein: An Introduction Albany: State University of New York Press. Translated by W. Brenner and J. Holley.

Shewe, M. and Shaw, P. (eds) (1993) Towards Drama As a Method in the Foreign Language Classroom. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Slade, P. (1954) Child Drama. London: University of London Press.

States, B. (1987) Great Reckoning in Little Rooms. Berkeley, University of California Press.

Stern, D. (2004) Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations: an Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, T. (1997) Theorising Language. Oxford: Pergamon.

Way, B. (1967) Development Through Drama London: Longman.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953) Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Wittgenstein, L. (1958) The Blue and Brown Books. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Please check the English for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Humanising Large Classes course at Pilgrims website.

|