Learning the jungle

Jamie Keddie

Jamie Keddie is an English teacher and writer. He is based in Barcelona and is currently working to complete his first book, Imperfect Tomatoes, which he describes as a self help book for all Spanish learners of English.

Email: jamiekeddie@hotmail.com

Menu

Confusion points

Outcomes

Acquired linguistic knowledge

2 learning/teaching models

Activity 1 - Google search

Activity 2 - What a wonderful world

Activity 3 - What if students keep using their own language?

Summary

References

On the road to learning a second language, there is a lot of linguistic understanding that students must acquire. A lot of this knowledge of how language works is not covered in standard syllabuses or text books. This article explores some of the linguistic knowledge in question and goes on to suggest some classroom activities which take language points as learning points.

Confusion points

Humans are expert language users but this does not mean that we understand the complex dynamics and intricacies that underlie it any more than a couch potato understands how a television works. But language learners are often assumed to do so and this often results in confusion points. For example: -

Case 1: A Spanish intermediate student of mine had previously been told that que had two possible translations in English - what and that. Taking this as gospel, he argued that the phrase mejor tarde que nunca could have two possible translations: -

When he was told that neither of these was a good translation, he was first sceptical and later upset.

Case 2: My class of Barcelona hoteliers became quite angry upon finding a violation of the adjective-nouns rule. Being hotel managers, one of them had become aware of occasionally being referred to as the person responsible by English-speaking guests (a noun preceding an adjective). My students demanded a reason for this desecration of what they had learned and wouldn't let me continue with what I had planned until they got one.

Case 3: I was once told by an advanced student of English that unlike other languages, English consists of a set of rules which must be blindly obeyed. Incredibly, the rest of the class was quick to agree with her. It was almost as if they had been spending so long looking at rules (mainly regarding grammar) that they had come to assume that the rules were in place before the language itself.

Case 4: My Catalan next door neighbour told me that he had given up English classes because he thought that he was stupid and beyond learning. His biggest complaint about himself was that he couldn't remember new words. I translated part of an article on secondary language vocabulary acquisition from a TEFL journal for him. In particular, he liked the concept that a learner has to meet an item 5 or 6 times or more before it sticks. He admitted that he had been overly-harsh on himself in expecting to retain vocabulary items after only one or two meetings.

Case 5: I had spent a lot of time planning a class which involved an excerpt from the film Pulp Fiction. Instead of doing what I had intended them to do with the script, my advanced students homed in on the many examples of "incorrect" English which peppered the pages. The result was a marathon student-teacher interrogation.

Case 6: The How do you know? dilemma. Examples: -

- If the verb put is the same in the past and present, how do you know if we are considering the past or the present?

- If the present continuous tense can be used to talk about actions happening now as well as future plans, how do we know which situation is being referred to?

- If to take someone out can also mean to kill someone in mafia language, how do members of the mafia know which meaning they are dealing with?

Outcomes

The frequency and outcome of such confusion points in any given language class depend on both the students and the teacher.

The student

It is a common observation that the more time an individual spends studying a foreign language, the better equipped s/he will be for learning a second or even a third one. It seems that there is a certain amount of linguistic understanding which some learners seem to be in possession of more than others, and this often depends on his/her language learning experience.

The teacher

As a learning guide, it is the teacher's responsibility to lead students away from confusion points when appropriate or to clarify and diffuse them when they arise. A teacher's competence in doing so will depend largely on his experience not only as a teacher but also as a language learner himself.

A positive outcome

On a good day, a confusion point can be turned into a fruitful and enlightening class discussion or experience.

A negative outcome

On a bad day, a confusion point can result in long-winded, defensive explanations, often in the learners' L1, which led to little but more confusion.

Acquired Linguistic Knowledge

When learning to drive, a little knowledge of how cars work goes a long way. Similarly, there are certain principles of language and language learning that if appreciated, will greatly benefit both language learners and trainee language teachers. What is the character of this acquired linguistic knowledge? Let us return to the 6 confusion points that were discussed above.

Case 1: The pitfalls of translation between a learner's L1 and L2

In assuming that a Spanish word as common as que could conceivably have only 2 possible English translations, my learner was failing to come to terms with the word's multifunctional nature. Beginners, especially, often assume that each word in one language can somehow be conveniently pigeonhole-translated into an equivalent word in another.

Cases 2 and 3: Understanding exactly what a language rule is

Because of the nature of the language beast, we cannot trap it with over-simplified and absolute, hard fast rules. Unlike the rules of a game, for example, most language rues are merely observations and are therefore descriptive rather that prescriptive. And due to the unreliable nature of rules dished out by teachers and text books, it can be good to regard them as "rules of thumb" that serve to assist rather than to dictate. With this in mind, learners can even be shown and encouraged to make their own rules based on language observation (corpus study, etc).

Case 4: Principles of learning and learner responsibilities

As was discussed above it may be worth pointing out some basic principles of language learning to students. As a slightly separate yet related issue, it is often important to point out that contrary to the implications of slick language school slogans such as Aprenderás de una vez (You will learn once and for all), language learning is an active process and learners, like teachers, have responsibilities.

Case 5: An awareness of variation and evolution in language

The existence of dialects for any given language (i.e. differences in grammar, pronunciation, semantics, language in use, etc) is often thought to complicate the job for the teacher and the learning process for the student. This results in a lot of unhealthy differentiation between "correct" and "incorrect" forms or a black and white distinction between American and British English. To make matters worse, language is constantly changing, often right in front of our very ears.

Contrary to what teachers and learners are led to believe, however, I find that any lesson that opens eyes to the real world of linguistic diversity and change will always be a beneficial one.

Case 6: Understanding language in use

For many years, language education concerned itself with the intense grammatical study of isolated components of the engine with little attention given to the actual car itself, never mind the driving, love and life that go on inside the vehicle. This phase, thankfully, seems to be coming to an end. When we do examine language in vivo as opposed to language in vitro, we come to understand a number of beautiful phenomena, some of which can be shared with our learners. For example: -

- The idea of context is more complex than we thought.

- Men and women conduct themselves differently in conversation.

- There is a huge array of writing and speaking styles and genres which undermines

the oversimplified distinctions of written versus spoken or formal versus informal English.

- Language can be thought of as a tool for self-expression.

2 learning/teaching models

In an article titled McEnglish in Australia, Scott Thornbury examines two possible language learning/teaching models - a transmissive one and a dialogic one. A transmissive model of language learning assumes language to be a subject consisting of a hierarchy of knowledge. In this model, language is acquired as this knowledge is passed or transmitted to students via a teacher, text book, syllabus, etc. Thornbury argues that although this may necessarily be the case for learning mathematics for example, it is certainly not the case for language acquisition (whether it is a L1 or an L2). He argues that language is a medium and not a subject. The dialogic model that he advocates is devoid of a syllabus and focuses on real communication. Any points of knowledge such as structures and lexis that arise as a result do so directly and internally from the communicators themselves and not from an imposed, external source.

By concentrating foremost on communication, a dialogic approach can be very effective in avoiding the types of confusion point that arise when, for example, we set out specifically to teach the difference between the past simple and the present perfect. But whatever approach we adopt, confusion points will always arise at some time or another.

Thornbury would seem to be reacting primarily against grammar-based syllabuses. But it is my opinion that there is a certain amount of knowledge associated with language and language learning that can be acquired through transmissive teaching approaches. Rather than dealing with grammar points, we are dealing with language points.

It is important to point out that I am not referring to university level linguistics, deep philosophy of language or anything of that sort. The knowledge in question may be a fact as simple as the one discovered by my Catalan neighbour (see case 4 above).

Of course, only time, experience and trial and error can really show learners the truth but we can help them on the way. What follows are 3 activities with 3 different language points.

Activity 1 - Google search

I was telling a class that I had seen my friend Bob playing Hammond organ with his funk band at the weekend. One of the astute grammar observers picked up on the fact that I hadn't used the definite article in doing so (i.e. I said playing Hammond organand not playing THE Hammond organ). He had read that the definite article is (always!) necessary in such cases.

This type of situation calls for a corpus investigation. Before demonstrating to our students exactly what a corpus is and how they are used in linguistic research, I find that it is good to start with a tool that will be familiar to all of them - the Google search engine. I gave my students the following activity: -

| Type the 8 following items into the Google search engine and take a note of the number of hits that you observe in each case: - |

| |

No. of hits |

|

No. of hits |

| |

|

|

|

| Play-the-guitar |

_________ |

Play-guitar |

_________ |

| Plays-the-guitar |

_________ |

Plays-guitar |

_________ |

| Played-the-guitar |

_________ |

Played-guitar |

_________ |

| Playing-the-guitar |

_________ |

Playing-guitar |

_________ |

|

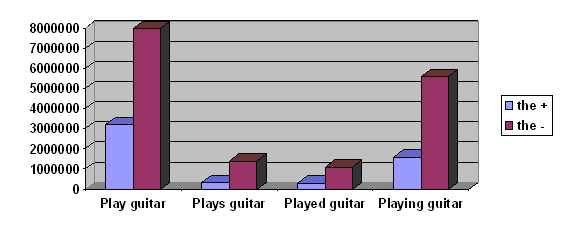

In arriving at a class consensus of results, a lot of big figure pronunciation was practiced. Here are the results that were obtained on 20th April 2006: -

| Play-the-guitar |

3.2 million hits |

Play-guitar |

8 million hits |

| Plays-the-guitar |

352,000 hits |

Plays-guitar |

1.4 million hits |

| Played-the-guitar |

305,000 hits |

Played-guitar |

1.1 million hits |

| Playing-the-guitar |

1.6 million hits |

Playing-guitar |

5.6 million hits |

Using my laptop, I made a quick chart on Word for Windows with this data (this took approximately 2 minutes).

Faced with this tangible, empirical evidence, the class then went on to draw their own conclusions and make their own grammar rule regarding the point in question. Although Google has not been designed for corpus-based language study and its usefulness in doing so is limited, it should not be underestimated as a demonstration of language in use.

This activity is a good introduction to the concept of corpus-based investigation and serves to strengthen the idea that when we set out to make a language rule, our first port of call should be an examination of the behaviour of language itself. Hopefully, students will then appreciate that it can be detrimental to demand simple language rules off the top of their teachers' heads when the real world of language is too complex for that.

[Suggest an online corpus or two]

Activity 2 - What a wonderful world

Personally, I am not a big fan of non-authentic texts. I feel that simplifying or "correctifying" language is one of the more reckless ways of keeping the tin opener away from the cans of worms. Although they will probably give the teacher an initial easy time, and the learners increased confidence, this is only short lived. Sooner or later, learners will meet authentic texts in which rules are broken and the language is different to how they have been taught (see cases 3 and 5). A class mutiny is not an uncommon result of this phenomenon.

Compare the situation with a mother who is neurotic about her 2-year-old child's habit of picking up and putting random objects in its mouth. Intervening in this apparently natural process may bring temporary peace of mind but may not do any favours for the development of certain aspects of the child's immune system in the long run (the immunocalibration hypothesis).

If we are going to continue using non-authentic materials in class, it may be worth raising students' awareness of them. In doing so, it is necessary to find a text that has both an authentic and a non-authentic version. Songs hold the answer.

It can be very expensive for publishers to use original musical recordings. It works out a lot cheaper if they get their own musicians to record new versions of well-known songs. In doing so, liberties are taken and lyrics are often amended.

To start off, do any good standard activity with a pedagogically produced song. The accompanying text book will probably suggest something good and provide any necessary additional materials. Next, play the original version of the same song and compare. Compare first musically and then lyrically.

My favourite song is What a wonderful world (Sam Cooke's version).

Don't know much about history

Don't know much about biology

Don't know much about science book

Don't know much about the French I took

But I do know that I love you. And I know that if you loved me too

What a wonderful world this would be

| Authentic version |

Non-authentic version |

| But I do know that I love you |

But I know that I love you |

Compare it with the text book version (from English file 1, 1996): -

I don't know much about history

I don't know much about biology

I don't know much about science book

I don't know much about the French I took

But I know that I love you, etc

By comparing the two versions, we can make students aware of two types of amendment made in non-authentic texts: -

1) A "correctification":

(The addition of the first person singular subject pronoun)

Authentic version Non-authentic version

Don't know much about history I don't know much about history

2) A simplification:

(The omission of the word do in line 5)

Authentic version Non-authentic version

But I do know that I love you But I know that I love you

This may seem a bit deep and complicated for a light-hearted English class, but my learners have all taken a genuine and enthusiastic interest in this point. In coming to understand that English grows wild, they can also come to accept that language in the real world breaks the "rules" that are taught in the classroom. This lesson can also have a great grammar edge to it - a juicy second conditional and "that do thing" (as in Oh I do like to be beside the seaside or I do hope that doggy's for sale).

Activity 3 - What if students keep using their own language?

I have a book by Jeremy Harmer called How to teach English (Longman, 1998). There is a chapter towards the end called What if? One of the sections is titled What if students keep using their own language? This is an everyday predicament for many teachers. If students can communicate perfectly in their own

language, why are they suddenly going to start doing it in another - one in which they are far less comfortable? The chapter mentions 5 different ways of dealing with the problem: -

| Authentic version |

Non-authentic version |

| Don't know much about history |

I don't know much about history |

1) Talk to them about the issue

2) Encourage them to use English

3) Don't respond to them if they speak to you in their own language

4) Create an English environment with anglicised names, posters, etc

5) Keep reminding them

All of these approaches can be worth considering depending on the students and the circumstances. One of my favourite ways of dealing with this problem is by showing the students the book itself. If students haven't given any thought to why they should be using their new language, then it is time for a class meeting.

This meeting should be formal and probably chaired by yourself. Students should be made aware beforehand that the whole class is going to have a serious discussion. You may want to bring up any additional issues and get everything off your chest in one go.

Go over the five suggested approaches (listed above) one at a time and decide as a class whether or not each one would be affective in combating the problem in question. Perhaps as a task, students could put them into an order of effectiveness. Subtly try and turn things around. By concentrating on your responsibilities as a teacher, your learners may sooner or later start to talk about their own. And they may even come round to seeing that the overall responsibility lies with themselves. It can then be good to ask the students why they continue to use their own language in class to the exclusion of English. Get their preoccupations out in the open (feels stupid, unnatural, etc). Of course give them all anglicised names and put up pictures of Big Ben and David Beckham if it was decided that this would help. And don't forget not to respond to them from time to time if they speak to you in their own language.

As a reactivation activity, get students to recall the five suggested approaches. For subsequent reactivations, wave the book in front of them and ask, "Do you remember this book? Well why are you talking in Spanish?" and have the same conversation all over again (thus revising any vocabulary or language that arose the first time).

A simply-written piece of pedagogic literature like this can be used as a text for language study like any other. Since it is of immediate relevance to students, it can also raise their awareness of a common problem that may be hindering learning in the classroom.

Summary

Van Lier wrote, "Knowledge of language for a human is like knowledge of the jungle for an animal." When learning a new language, the pitfalls in the jungle become deeper. There is a certain amount of knowledge and understanding of the language jungle that learners will have to pick up for themselves. But there are also principles of language and language learning that can be demonstrated to them. Via the questions that they ask, students themselves are demonstrating the need to address such issues. Such language points are often neglected in syllabuses but as teachers and jungle guides, we can find ways of confronting them.

References

Fessler, D.M.T. and E.T. Abrams (2004) Infant mouthing behavior: The immunocalibration hypothesis. Medical Hypotheses 63(6):925-932

Harmer, Jeremy (1998) How to Teach English. Longman

Oxenden C. and Seligson, P English file 1 (1996). Oxford University Press

Thornbury, S. McEnglish in Australia (1996)

Online: www.teacing-unplugged.com/mcenglish.html

Van Lier, L. (2000) From Input to Affordance: Social-Interactive Learning from an Ecological Perspective, in Lantolf, J.P. (Ed). Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Please check the Expert Teacher course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Skills of Teacher Training course at Pilgrims website.

|