The Analysis of “Critical Incidents” as a Way to Enhance Intercultural Competence

Grazyna Kilianska-Przybylo, Poland

Dr Grazyna Kilianska-Przybylo is a lecturer and a teacher trainer at the University of Silesia (Sosnowiec, Poland). She is interested in language pedagogy, methodology of ELT and second/foreign language acquisition. Current interests are: foreign language teacher education and teacher professional development; reflective teaching and intercultural communication. E-mail: grazyna.kilianska-przybylo@us.edu.pl ; grazynakp@tlen.pl

Menu

Introduction

Background

Examples

Conclusions

References

The aim of this article is to discuss the role of critical incidents (or Critical Incident Technique) in initiating students’ reflection on culture-based behaviour, and consequently, developing their intercultural competence. Additionally, the article provides some comments on the implementation of this technique and feedback obtained from the students (samples of critical incidents).

There is a multitude of reasons why intercultural competence is crucial. First of all, it largely contributes to successful communication. As Ronowicz (cited by Ronowicz & Yallop, 1999:1) puts it: “the achievement by the learners of cross-cultural competence, i.e. the ability to relate to differences between the learners’ native and target cultures” would enhance the effectiveness and quality of communication.

Another reason deals with the promotion of understanding, tolerance, empathy, and refers to the initiatives of Council of Europe and ECML, which proclaimed Year 2008 as a year of Intercultural Dialogue (www.coe.int; www.ecml.at). Finally, intercultural competence is essential to promote professional and educational mobility. We must remember about growing popularity of EIL (English as an International Language), which is used as a means of communication in international encounters.

The concept of intercultural competence, however, is a complex construct to deal with. Byram (1997: 5-7) enumerates some components of intercultural competence that must be developed, namely: intercultural attitudes (curiosity and openness, readiness to suspend disbelief about other cultures and belief about one’s own); knowledge (of social groups, of products and practices); skills of interpreting and relating; skills of discovery and interpreting and critical cultural awareness.

Hanley (1999) is of the opinion that to build intercultural competence, we need some “ingredients”, namely: self-knowledge (i.e. introspection and self-understanding), experience (i.e. unmediated experience, encounters with other cultures) and positive change.

Ronowicz (cited in: Ronowicz, E. & Yallop, C. 1999: 8) believes that encounters with other cultures lead to: comparisons, value judgments or (verifying) cultural stereotypes; considerable stress. That is why, the process of building intercultural competence requires and is dependent on some cognitive and affective changes in a person. Glaser et al. (2007: 16) nicely summarize this point, saying that “the development of intercultural competence (…) involves the learning of certain knowledge and values and the re-evaluation and discarding of existing ones which may conflict with them. Alongside learning, unlearning therefore takes place and this is an iterative process”.

Bearing this in mind, we might risk a statement that critical incidents may help to develop intercultural competence. Critical incidents refer to positive or negative situations/ events that are experienced. According to Tripp (1993: 24), critical incidents are indicative of underlying trends, motives and structures; that’s why they significantly contribute to one’s understanding of some phenomena. Analysis and evaluation of critical incidents enable to reflect upon the nature of some phenomena (here: cultural differences; the impact of culture on human behaviour and cognition).

Tripp (1993: 24-25) claims that “critical incidents appear to be ‘typical’ rather than critical at first sight, but are rendered critical through analysis. He says that there are two important stages in the creation of critical incidents, namely: the production of an incident (observation, recall and description of what happened;) and analysis (finding more general meaning of the incident and its evaluation).

Tripp (1993) and James (2001) believe that the value of critical incidents lies in the questions that people are supposed to answer in the process of analyzing the incident. The following questions may help to recall and analyse the incidents.

WHO?

WHAT?

WHEN?

WHERE?

HOW?

WHY?

What really happened?

How did I feel?

What do I think about it now?

What did I learn?

Part of my professional duties require raising students’ awareness of culture- bound behaviour and developing their understanding and knowledge of successful intercultural training. To achieve this, I regularly implement a series of tasks, “Brainstorming and analyzing ‘critical incidents’” being one of them.

Task : BRAINSTORMING AND ANALYSING ‘CRITICAL INCIDENTS’

Aims:

- to raise students’ awareness about culture- bound behaviour

- to trigger students’ recall of the critical incidents they’ve encountered

- to raise students’ awareness about the impact of culture on language, human behaviour and cognition

Step I

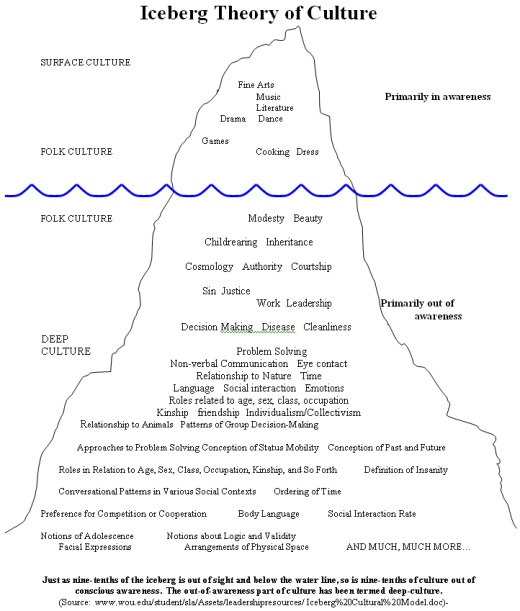

Students are exposed to Iceberg Theory of Culture (Weaver, 1986, source: www.wou.edu), which is presented in Appendix 1. Students are requested to express their opinions and give examples of culturally- based behaviour. Iceberg Theory of Culture serves as a cue/ prompt that facilitates their responses, yet it is optional.

Step II

Students are invited to share critical incidents with others.

Brainstorming and analyzing critical incidents usually result in fruitful and prolific discussions. Below, we can find some examples of critical incidents generated by the students:

- One student reported that while staying with an English family, she was surprised to notice that their English dog answered and reacted only to the target language. “He DIDN’ T respond to any orders given in Polish”- the student looked astonished while describing the whole situation.

- Another student was shocked to notice that an American Mum gives her child COLD milk for breakfast. The student reported: „She just opened the fridge, took out milk and poured it into the glass.” (In Poland, because of climate, it is good to start a day with something warm to eat. This unwritten rule applies particularly to raising up children).

- Yet, another student noticed „intercultural differences” in the sense of cleanliness. She was surprised to discover that clearing up a bathroom means something different for Polish, English and Chinese people. She said: „What was clean for Chinese people was not necessarily clean for me. In fact, it was a complete mess. I dreaded of going inside and having a shower. I had to tidy the place myself first.”

Critical incidents seem relevant and useful because they treat someone’s personal experience as a starting point for analysis, which then contributes positively to personal enrichment and development of self-knowledge.

Another thing worth mentioning concerns the attitude and motivation of the students involved in the analysis of critical incidents. Students usually get highly absorbed in discussions. Their reports or accounts of the events are usually extremely personal and emotionally-loaded. Critical incidents generated by students may also serve as a source of knowledge about cultural differences for other participants. To sum up, we may say that the value of critical incidents lies in the combination of cultural, linguistic and personal elements into one task.

Byram, M., A. Nicholas & D. Stevens. (eds). (1997) Intercultural Competence in Practice. Multilingual Matters, (electronic version)

source: http://books.google.pl/books date: 28.11.2008

Glaser, E. et al. (2007) Intercultural competence for Professional mobility. Graz: Council of Europe Publishing

Hanley, J. (1999) Beyond the tip of the iceberg. Five stages toward cultural competence. Reaching today’s youth, vol.3No2.pp.9-12;

source: www.cyc-net.org./reference/refs-culutralcompetence.html ; date: 20.10.2008

James, P. (2001) Teachers in Action. Tasks for in-service language teacher education and development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Ronowicz, E. & Yallop, C. (eds). (1999) English: one language, different cultures. London: Conitnuum

Tripp, D. (1993) Critical Incidents in Teaching. Developing Professional Judgement. London: Routledge.

www.ecml.at

www.hsp.org/files/culturaliceberg2.pdf

www.wou.edu/student/sla/Assets/leadershipresources/Iceberg%20Cultural%20Model.doc

Please check the British Life, Language and Cultur course at Pilgrims website.

|