Challenges for Polish Learners of English from the Implementing of Learning Strategies in the National Curriculum: A Report

Jacek Wasilewski, Poland

Jacek Wasilewski has been an EFL senior teacher with 22 years experience in ELT. He is employed at the University of Podlasie in SIEDLCE-Poland where he teaches conversational classes. His current interests are: segmental phonetics, phonology, sociolinguistics, spoken discourse, autonomy and learning strategies and ethnolinguistics. E-mail: jackwas@interia.pl

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

The search for a strategy definition

The typologies of learning strategies in ELT

The role of learning strategies in L2 learning process

The perception of autonomous foreign language learner

The role of English learner in Polish schools prior to the year 2000

Teaching as product

The new requirements in teaching and learning English after the year 2000

Declarative and procedural knowledge

Conclusion

References

This report aims to simultaneously highlight the benefits and challenges that English language learners face up due to the way in which language learning strategies are implemented in foreign language education. It also presents two contrasting philosophies of foreign language teaching and learning. The first of these was prevalent in the 1980s and 90s and the second one has come into use over the last few years.

After a long-lasting period of concern with the issues of the foreign language (FL) acquisition and learning at Polish schools, recent years have seen the new recommendations put forward in 1999 by the Polish Ministry of Education with regard to the state of the art methods and techniques which must be introduced in the FL educational system. There has appeared a vast increase in the amount of publications devoted to the area of second language acquisition (SLA), the first fully-fledged approach in methodology called discourse based approach and particularly developing of language learning strategies and learner autonomy in the process of foreign language training.

For this reason, teaching English as a foreign language methodology has exhibited a great interest in putting emphasis on communicative language teaching (CLT), which meant implementing self – directed learning and the principle of an autonomous learner in all types of Polish schools.

As a result, a gradual but vital shift in the foreign language education has been observed over the last years. The change has really referred to putting less accent on teachers and teaching and greater emphasis on learning and learners. The attention was centered around how students process and store the bulk of information resulted from the introduction of CLT and what types of new techniques learners use to understand, learn and remember to simply become a successful English language user.

The present paper is intended to provide a comprehensive review of learning strategies in general, their world – famous taxonomy and the importance of strategies in the learning process. A fundamental aim of this report is to present the Polish context in which the concept of learning strategies and learner autonomy have gained momentum over the last years.

The paper consists of two chapters. Chapter one introduces the notion of strategy and its different sections. Chapter two takes a look at teaching English in Poland prior to the new educational reform and provides a short characteristic of the Polish system. In contrast, it focuses on the main features of the national curriculum and explains the key issues of the contemporary approach.

In everyday life we use different types of strategies both consciously and subconsciously. We frequently encounter situations when we have remembered something important and then we try to invent various ways of facilitating our memorization. For instance, we pick up words or rhymes to associate them with definite situations or events.

Similarly, during our conversations with a particular individual when we find it hard to understand the flow of speech, we make every effort to devise different ways of maintaining communication. We either pretend that we know perfectly well what is going on or we simply change the subject of our conversation to show how eloquent we are.

Such a change of topic or even making pretence of understanding a communicative act appears to be a kind of a strategy.

To fully comprehend the meaning of the term “strategy”, it is worth referring to the advanced Macmillan dictionary which presents the following interpretations:

- strategy - a plan or method for achieving something , especially over a long period of time,

- the skill of planning how to accomplish something in war or business.

Another well-known English Longman Contemporary dictionary defines strategy as:

“a well planned series of actions for achieving an aim especially success,

also a skillful planning in general “.

A broader meaning was suggested by the Associate Professor of the University of Alabama- Rebecca Oxford (1990, p7) who referred to the ancient Greek term “ strategia” meaning

“the art of war or practical and military skills utilized by a general”

She added that strategy involves management of troops, ships, etc and related to the word “tactics” which, if reasonably organized, may be wonderful tools to achieve the success of undertaking.The perceptiveness of the role of strategies has also become vital in the last decades in the field of teaching and learning a foreign language. Research carried out by many linguists and educators has aimed at identifying the factors affecting the second/ foreign language learning process (L2). These studies have become very popular amongst researchers who have listed certain features which characterize “a good leaner”, but it seems that it would be highly advisable to make a similar array of language behaviours which might be used by less gifted students.

The question arises: what do good learners have in common? It has been indicated by Naiman et al. (1978) that learners who were to be good at L2 learning shared the following features:

GLL - (good language learners) are

- aware of the type of learning that suit them best

- more in the class visibly or not

- are conscious that a language is not only a complex system but it is also used for a purpose

- constantly expand their language knowledge

- develop L2 as a separate system

- realize that L2 learning is very demanding- it is like taking up a new personality in learning a foreign language

From the above-mentioned list one could say that a good learner is a responsible, risk-taking, courageous and well organized learner with a far reaching objective- the goal which may be achieved if so called learning strategies are implemented during the L2 learning process.

The first studies into learning strategies began in the 1960s but those who first explained them were (Weinstein and Mayer, 1986). They defined learning strategies quite broadly as:

“ behaviours and thoughts that a learner engages in during learning”

They added that:

“ such actions are intended to influence the learners encoding process”

Then LS were accurately interpreted by Mayer (1988) as:

“ behaviours of a learner that are intended to influence how the learner processes

information” (p.11).

The term learning strategies used in ELT have been defined by many researchers who provided us with different definitions and interpretations.

Early on, Tarone (1983) defined LS as

“ an attempt to develop linguistic and sociolinguistic competence in the target

language also called as an interlanguage competence” ( p. 67).

Rubin (1987) wrote later that:

“ LS are strategies which contribute to the development of the language

system which is constructed and affected by the learner” ( p.22).

O’Malley and Chamot (1990) interpreted LS as:

“ the special thought or behaviour that students use to help them

comprehend, learn or retain new information” (p.1).Further , Ellis (1994, p.712 ) defined learning strategies as:

“ a device or procedure used by learners to develop their interlanguages (….). Learning strategies account for how learners acquire and automatize L2 knowledge. They are used to refer to how they develop specific skills (….).

When considering language strategies one cannot omit specific examples and definitions. One of these provided by the previously mentioned author Rebecca Oxford. In her books for teachers Oxford presents very characteristic examples of LS. For example on learning English as L2:

“ Trang watches US TV , soap operas, guessing the meaning of expressions and predicting what will come next”

By analyzing this short context, Oxford gives a helpful definition of learning strategies:

“Language learning strategies……. specific actions, behaviours, steps or even techniques that learners use to improve their progress in developing language skills such as speaking , listening, reading, writing”

These strategies can facilitate the storage, retrieval or use of the new language.

As can be seen from the above analysis, there is no unanimous definition of learning strategies and the description of the selected ones shows an evolution over time from the earlier focus on the product in teaching and learning of linguistic and sociolinguistic competence to a greater accent on the process and the features of language learning strategies.

Product and process are considered as skills, activities and goals accordingly.

Much research has been done to identify and classify learning strategies. In the 1970s the study of successful learners in the learning process considerably contributed to gathering data regarding the most often actions performed by foreign language learners. Thus there appeared various LS classifications.

One of the best known ones is that by O’Malley et al. (1985). They classify them into metacognitive, cognitive and social/affective. Metacognitive strategies cover selective attention, planning, monitoring and evaluation; cognitive strategies involve rehearsal, organization, inferencing, summarizing, deducting, imagery, transfer, elaboration and social/affective encompasses cooperation, questioning for clarification and self talk.

What remains beyond all doubt is that Rebecca Oxford ( 1990, p. 18-21) suggested the most detailed taxonomy which seems to be complete and even covers the essential techniques called compensatory strategies such as guessing intelligently and overcoming limitations in speaking and writing.

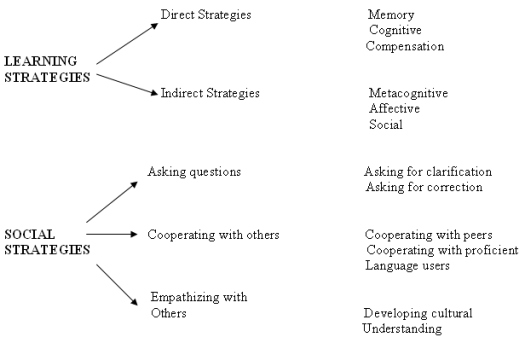

The author sees the aim of LLS as being oriented towards the development of communicative competence (p.9). She divides language strategies into two main classes, direct and indirect, which are further subdivided into 6 groups.

The following diagram illustrates specific language strategies.

Source: Language Learning Strategies ( R.L. Oxford 1990 )

In Oxford system, LS referring to metacognitive group help learners to regulate their learning. Affective strategies are concerned with the learner’ emotions such as feeling confident in L2 learning, while social strategies lead to a desirable interaction with a target language. One of the most important groups- cognitive strategies are simply mental techniques or behaviours learners use to make sense of their training, and those techniques which help learners store information belong to memory strategies. To overcome any gaps in communication between speakers Oxford suggests compensation strategies.

It seems clear that learners encounter many different problems with L2 acquisition and conscious learning. Bearing in mind the fact that new methods of teaching like CLT or natural method have been implemented into the Polish state school curriculums, one must argue that the amount of new information processed by learners has noticeably increased in language classroom. Learners perform a big variety of tasks and have to process the new input they are exposed to.

Language learning strategies appear to have become good signals of how learners approach tasks or solve problems encountered during L2 learning process In other words, LS serve as pointers giving teachers valuable clues about how learners plan, tackle language problems, assess the situation or choose appropriate skills, techniques or behaviours in order to understand, learn and keep in mind new input presented in class. Fedderholdt (1997, p.1) in referring to learning strategies argued that those learners who are able to use a wide variety of LS can improve their language skills in a more efficient way.

How do L2 learners change if they use language learning strategies?

First of all, cognitive strategies help solve new problems, next metacognitive ones improve organization of learning timing, self-monitoring and also enable learners to participate in self-evaluation. What is more, socio-affective strategies give students a chance to ask native speakers to correct their prosodic features in a foreign language. Lastly, by developing these three areas one can help learners to build up their independence and finally autonomy which leads further to taking control of their own process of learning.

An important advantage of LS has been observed and singled out by Oxford (1990, p.8) which refers to LS contribution to the development of the communicative competence of the students. She states that learning strategies, as mentioned before, are tools for active and self-directed movement essential for improving communicative competence.

According to Hedge ( 2000, p.86), activities which are prepared for strategy training may help learners to reflect on learning , other class actions equip learners to be active during L2 process and encourage students to monitor and check their progress.

Language learning strategies are closely linked with the concept of learner autonomy and independence in L2 learning. This notion has gained momentum over the last two decades and it refers to the shift of responsibility from teachers to learners with result of a learner-centred kind of learning. Such a reshaping of relations between teachers and learners in class has been conducive to creating a new learning and teaching situation. In brief, a learner has been thrown into a totally unknown perspective and has been regarded as an individual with the capacity for decision-making, independent action, critical reflection, planning practice opportunities or assessing his /her progress.

To find a definition of autonomy, we should quote Holec (1981, p. 3, cited in Benson & Voller, 1997, p.1 ) who describes the term as “ the ability to take charge of one’s learning, further in the relevant literature for instance, Little (1991) defines autonomous learners as those who:

- take initiatives in planning and executing learning activities,

- regularly review learning and evaluate its effectiveness,

- share in the setting of learning goals,

- explicitly accept responsibility for their learning,

- understand the purpose of their learning programme

What seems to be vital in understanding the autonomy itself is the fact that learner autonomy is a goal, but it is also regarded to be a long learning process foreign language learners may face both in and outside of class. One should also add that autonomy is a process and a product of learning. This means that in order to develop autonomy, learners need opportunities to take responsibility, but they also want knowledge and skills to do this successfully. No matter at which stage of learning students will be involved in developing autonomy, they must be aware of the lengthy operation. Besides, there must be certain conditions fulfilled in order for autonomy to grow. These conditions relate to learner needs, motivation, learning strategies and language awareness.

It appears equally important to present the attitude towards autonomy in class put forward by Luciano Mariani (1997).

For him, the whole process of becoming autonomous is not considered to be an easy undertaking. The author states that learners undoubtedly have a subjective or objective attitude towards the concept. For some learners being autonomous may mean being challenged in other words, it looks like an invitation to a contest or trial of any kind. By quoting the Longman Contemporary Dictionary, he adds that it is something that tests strength, skill or ability especially in an interesting way.

Such a reasoning and with all those above aspects about autonomy in mind allow us to put a question to oneself, namely if all learners in Polish state schools are ready for so a brave action in their learning and whether they feel enthusiastic about such a determination to deal with hard duties. It seems reasonable to assume that students may find it hard to achieve this goal given that they have to cover far too many subjects in class apart from learning English.

To put a long story short, one must emphasize that teaching in Poland before the educational reform in 1999 differed widely from the way the language has been taught over the last years.

The main difference lies in the teaching principle which prevailed at that time. The language teaching based on the audiolingual method and was related to a behaviorist psychology. Practically speaking, it meant that the role of learners was dominated by a teacher who acted as a master in class. Learners hardly ever took a pro-active role in the learning process. It is true that there was no chance for generating ideas or availing oneself of learning opportunities. Rather, students simply reacted to various stimuli of the teacher and the process was definitely a matter of rote memorization.

Because of the influence of the Skinner’s psychology on the way the language was trained, the individuals were never left freedom of choice. It was the teacher who tried to adapt his methodology and materials to the learner like a doctor writing out a prescription.

It seems noteworthy to point out that at that time teaching mainly focused on mastering grammatical system of the language and its basic functions. Linguistic elements were of great interest to teachers because it was thought that the knowledge of grammar was the most important in the L2 learning process.

As far as the syllabus is concerned, it is certain that grammatical syllabuses became popular then and what characterized them was the selection and gradation of syllabus input.

Unfortunately, because of focus mainly on the knowledge and skills which were acquired as result of instruction this type of curriculum came under strong criticism during the 1970s. The most popular coursebooks used by teachers were as follows:Books by L.G. Alexander, Streamline English by B. Hartley, books by Kernell and Cook – English for Life and a little later Matters by Ian Bell and Blueprint by B. Abbs, Success with English by G. Broughton and others.

The new educational reform in Poland was introduced in 1999 and it not only referred to the radical changes in the structure of the Polish system but also put great emphasis on the core curricula with regard to specific school subjects.

Learners are usually given freedom of choice as far as language education is concerned, but for the most part English is chosen as a first language taught at schools. Among other languages that have become popular are German, French and Russian.

What seems to be vital in the new reform is the wider significance attached to the newly introduced subject programmes. The major priority has been given to the objectives, content, teaching recommendations, learning outcomes and evaluation of foreign language curricula.

To present the main requirements as regards teaching and learning foreign languages in Poland, the below supplement illustrates the essential items:

| content |

objectives |

| General points |

Achievement of a language competence level enabling basic communication with FL speakers |

| Acquisition of language skills enabling efficient language communication on basic life matters in contact with foreigners |

| Enabling learners to use a given FL as a tool to obtain info in the cognitive process |

| Enabling learners to participate in the multi-lingual and multi-cultural reality of contemporary Europe and the world |

| Communication field |

A certain degree of priority is accorded to oral skills over reading and writing skill at FL lessons |

| LISTENING |

| SPEAKING |

| READING |

| WRITING |

| Using a wealth of strategies which help develop language modes and skills |

| Cognitive and affective field |

Foster Independent Learner |

| Cognitive and affective field |

Self-evaluating language process |

| Ability to ask and give help in activities or projects carried out in pairs, groups |

| Getting used to global understanding of oral or written texts |

| Foster Personality Development |

| Develop motivation to learn a FL |

| Stimulate imagination, active involvement and creativity |

Source: Supplement to the Eurydice study on Foreign Language Teaching in Europe, (2001)

From the methodological point of view, it can be easily seen that the core curriculum recommends the utilization of the communicative approach used in class, teachers are obliged to use as many authentic materials as possible, are encouraged to correct mistake only when they block communication and in addition, the programme insists that communicative activities and tasks be implemented in class interaction.

Another essential aspect of the new regulations is an educational innovation with regard to the modified MATURA exam format, in brief an obligatory school leaving exam in English. Before the reform the final exam was single-handedly prepared by English teachers at various secondary schools, which meant serious discrepancies in size, degree and level of English between Polish educational institutions. Nowadays since the format and content of the exam appear to look the same everywhere and have become apparently comparable to the high specifications drawn up for the FCE Cambridge exam, it is tempting to suggest that plenty of learners of English at Polish schools will not be geared up to pass the new format of an extended exam with flying colours.

The new above requirements introduced into the Polish national curriculum after the years 2000 have given rise to a greater interest among Polish educators in the distinction between explicit and implicit knowledge. Above all, the newly prepared scheme of the school leaving exam made teachers feel convinced that Polish learners must develop the ability to use knowledge successfully in L2 learning.

Following the explanation and contrast made by J. Anderson (1980:1983:1985) between these two types knowledge, one has to point out that declarative knowledge i.e. “knowing that “ which usually consists of information as word definitions, facts, rules or sequence of events is not sufficient to possess it in order to pass the new school leaving exam at Polish schools. This knowledge referring to the acquisition of grammar only may be a good step before the next type of knowledge has to be gained. Anderson calls it procedural one, that means “knowing how”, in short an ability to show how to transfer competence in a foreign language into performance. Since the procedural knowledge is associated with production in a FL, it explains how important it is to succeed in mastering a foreign language According to Kasper (1983), this knowledge identifies a number of sub components- certain strategies like bottom-up and top-down processing and inferencing.

The present report has been inspired by the recent developments in the area of language learning strategies and learner autonomy. While looking at the importance of learning strategies in chapter one of this report and other positive features of the new communicative approach incorporated in L2 learning, it is imperative that Polish learners of English will become fully acquainted with the benefits of LS may bring to them but it is also essential that they should rise to the challenge of introducing the issue of learning strategies and learner autonomy in Polish schools.

The points made in chapter two have made it clear that English learners will need a lot of skill, energy and determination to cling to the new belief in an English learning process. It seems true and inevitable that Polish students must break away from habits or old ways of thinking about English learning. It is high time to forget about learning grammar as a final product of the whole process in mastering English. Furthermore, it would be desirable to remove the psychological barriers of being dependent on a teacher throughout the time of preparation for the ‘Matura’ exam.

The main assumptions of the new educational reform which pointed to focus on developing skills and abilities instead of mechanical accumulation of knowledge by Polish learners, curriculum based on new coursebooks (modules) instead of individual courses or introduction of (cross-curriculum) project work allow us to make sure that the process of learning and teaching will be directed towards learners. Thus, they are obliged to assume greater responsibility for the effects of learning. Consequently, the new approach will put new demand on learners that will be mainly concerned with developing learner autonomy.

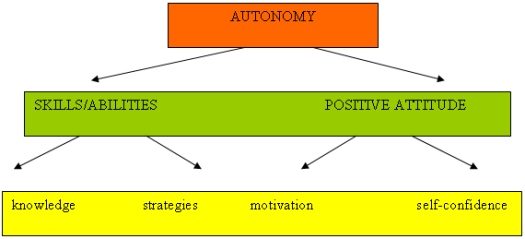

If we look at the general concept of autonomy presented by Littlewood ( 1996 ), we will be able to understand what may be required of Polish learners of English.

From the above diagram, we can state that both factors are important that learners should become autonomous. In a foreign language class it may mean that Polish learners must be open to communicative situations, have the ability to use language creatively, take risks as far as errors are concerned and have the ability to use communication strategies most effective for learner profiles. Further, learners should be self-directed in learning in and out of the class, be raised an awareness of what methods, strategies and techniques seem the most appropriate and suitable for a given learner according to their learning style. Next, English students in Polish schools must develop an ability to express without inhibition their own thoughts and emotions, create learning context not only in class but also outside and equally important, Polish learners should be reflective on their learning and know the art of self- evaluation and self-assessment.

It can be inferred from the above facts that the learning process of the new approach would seem to be extremely challenging for international learners of English but the process might be possible to be facilitated and achieved thanks to the teachers’ help. It is beyond doubt that in the new learning environment the way of teaching also undergoes a certain change , which may become beneficial both to learners and teachers as well. First of all, one has to mention a number of new roles a teacher plays in class. As Hedge ( 2000) puts , their functions range from a manager of activity , a classroom organiser, a guide , language resource, a corrector of errors, a monitor, a diagnoser to a facilitator, participant and even prompter. It is easy to notice that the list is numerous and it may make some teachers feel scared of the demands they have to cope with in a communicative classroom. Obviously, it requires of teachers to build up their competence and confidence in satisfying their roles and it also entails in-service training. But on the other hand, teachers are able to take a greater interest in what is really going on in class. Thus, they may devote more time to the observation of learners and their behaviours. It gives them an opportunity to look at the class from a teacher – research perspective, which eventually contribute to improving their teaching styles.

To sum up, it is tempting to highlight that all these changes such as introducing CLT with its autonomy and learning strategies in class are culturally specific. It generally means that not all initiatives are even possible to display in some parts of the world. It stems from the fact that there is a number of different educational policies , approaches and beliefs in a real classroom pedagogy.

Anderson, J. (1980:1983:1985): cited by Ellis, R. (1990). Instructed second language acquisition. R. Ellis 1990, p. 117.

Ellis, R. (1994): The study of second language acquisition. Oxford: OUP

Faerch, C. & Kasper, G. (1983): Procedural knowledge as a component of foreign language learners communicative competence. In Boete, H. & Herrlitz, Utrecht.

Fedderholdt, K. (1997): Using diaries to develop language strategies on internet. (p.1)

Hedge, T. (2000): Teaching and learning in the language classroom. OUP.(p.86)

Holec, H.(1981): Autonomy in foreign language learning. OUP.(p.3)

Little, D. (1991): Learner autonomy. Definitions, issues and problems. Dublin

Littlewood, D. (1996): Autonomy: an autonomy and a framework system. Vol.24.No4, Elsevier Science LTD

Mariani, L. ( 1997): Teacher support and teacher challenge in promoting learner autonomy.

PERSPECTIVES: Journal of TESOL –Italy- Vol.XXIII, No 2 FALL

Mayer, R. ( 1988): Learning strategies: An overview. New York: Academic Press

Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners (2006)

Naiman, N. Frohlich, M. Stern, H. H. & Todesco, A. (1978): The good language learner. Toronto, Ontario Institute of Studies in Education

O’Malley, J. & Chamot, A. U. (1990): Learning strategies in second language acquisition. CUP

O’Malley, J. et al. (1985): Learning strategies used by beginning and intermediate students, Language learning.

Oxford, R. (1990): Language learning strategies. What every teacher should know. NY: Newbury House ( pp.1-9,18-21)

Rubin, J. ( 1987): Learner strategies: theoretical assumptions, research history and typology, Prentice Hall

Supplement to the EURYDICE study on Foreign Language teaching in Schools in Europe, National Description of Poland, 2001.

Tarone, E. (1983): Some thoughts on the notion of communication strategy. London: Longman

Weinstein, C. &Mayer, R. (1986): The teaching of learning strategies: handbook of research, 3 rd edition. NY: Macmillan.

Please check the Train the Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|