Editorial

This article first appeared in Modern English Teacher Volume 16/4 October 2007

Practising the Grammar of Spoken English

Simon Mumford, Turkey

Simon Mumford teaches EAP at Izmir University of Economics, Turkey. He has written on using stories, visuals, drilling, reading aloud, and is especially interested in the creative teaching of grammar. E-mail: simon.mumford@ieu.edu.tr

Menu

Forbidden words

Reduction drills

Headers and tails coin toss

Hesitation drills

Circular sentence drill

Interjection noughts and crosses

Two and three step requests

Interjection story

Vague language pictures

Phrasal chains

Conclusion

Reference

The publication of Cambridge Grammar of English (Carter and McCarthy, 2006) is a significant event in the analysis of the English language, since elements of native-speaker spoken English grammar and been recorded and described in a detailed and comprehensive way on the basis of a large corpus. Teachers can now point with confidence to features such as vague language, headers and tails, and ellipsis as the norm in informal speaking situations. Assuming that at least some students will need or want to learn these spoken grammar forms, there follow some suggestions for teaching them productively. All references are to Carter and McCarthy (2006).

Subjects and auxiliary verbs at the beginning of sentences may be omitted where they can be understood from context (p.182). The simplest way to practise this kind of ellipsis is to forbid the use of pronouns and auxiliaries in affirmative and interrogative sentences, and pronouns in negative ones. Two students hold a conversation, monitored by a third, who, when hearing a forbidden word, takes the place of the offender. Example:

A: Went to France last week.

B: Really? Have a nice time?

A: Not bad. Saw Paris.

B: Did you go to the Eiffel Tower?

C: (as judge) You said ‘Did you’.

C: (taking B’s place) Didn’t feel well yesterday.

A:Eat too much?

To practise ellipsis, write the following dialogue on the board and drill it, starting with the full forms and reducing them by saying the dialogue repeatedly, faster and faster. The non-essential words (in brackets) should fade away until they are omitted completely. The aim is to reduce the time taken to say the dialogue to about ten seconds.\

Customer: (Have you) Got any black biros?

Assistant: (There are) Some over there.

Customer: (Could you) Give me a packet of tissues, too, please.

Assistant: (Would) These (be) all right for you?

Customer: (They will be) Fine.

Assistant: (That’s) One twenty please.

Customer: There you are.

Assistant: Thank you.

To show why such ellipsis is necessary, set up a shop role play with four times as many customers as assistants, representing a busy shop. Since customers have to visit every assistant, they will have to queue. The idea is to finish the transactions as quickly as possible, to reduce queue length and waiting time.

My father is happy now can appear in spoken English as My father, he’s happy now (header),or He’s happy now, my father (tail). Headers and tails are ‘standard features of informal spoken grammar’ (p. 192). Say a short sentence, eg John lost his wallet, and toss a coin. Ask the students to change the sentence with either a header or a tail while the coin is in the air. When the coin lands, tell the students whether it was heads or tails. If heads, students who used a headerare the winners and vice versa. Students play in threes, one to toss and say a sentence in its conventional form (these can be given on a piece of paper if necessary) and two callers, who change the sentence with either a header or tail.

Pausing and repeating, especially at the beginning of utterances are common (p. 172, 173). Write a sentence on the board and ask students to repeat at normal speed. While they do this, hold your hands out in front of you and move them apart so that when you reach the end of the sentence, they are at full stretch. Explain that you want the students to say the sentence at the speed which you move your hands outwards. The second time, include a few hesitations, that is, stop your hands in the middle for a few seconds. You can practise repeating parts of the sentence by moving your hands closer together and further apart again, imitating native speaker hesitation and repetition. Include some hesitation symbols, e.g. open your fingers wide to signal er, umm.

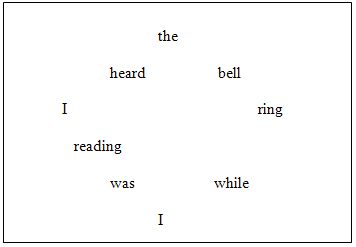

Writing a sentence in a circle rather than in a line makes it easier to say in different ways, so for example the sentence I heard the bell while I was reading can be drilled asWhile I was reading, I heard the bell ring. We can also practicehesitations and repetition: While I was reading...I heard the bell ring while I was reading, or even While I was... while I was reading...I heard...I heard the bell... bell ring. As the words are written in a circle, you can move your finger round the sentence, back and forward, to get the desired amount of repetition.Another possibility, using ellipsis and reduction, isheard the bell ring while reading.

Interjections can be divided into those which express strong emotion: damn, wow! (p. 224) and those which act as discourse markers: right, so, well (p. 212). Draw the grid below and put students into teams or pairs to play noughts and crosses. Assign one symbol to each team, students choose a square simply by saying the phrase inside it. For subsequent games, rub out the words (perhaps leave the first letter) and let them do it from memory. The interjections can be contextualized by asking students to say them as if they were expressing these thoughts on the game itself, signaling, for example: surprise at a move (wow!), the end of a turn (right), disappointment (Oh no!).

| Oh well! |

Well... |

Wow! |

| Oh no! |

Gosh... |

I see! |

| Oh dear! |

Right. |

So... |

Questions may be prefaced with another question to produce two step questions (p. 201). This would have the effect of making questions used as request less direct (therefore, presumably, more polite). This can be demonstrated with a metaphor, where a long single step towards the listener represents a very direct request and several shorter steps represent a broken down, less threatening one, since the listener has been prepared by the questions. Compare:

Dialogue 1

A:Can I borrow your umbrella?(taking one long, intimidating step towards B)

B: Err, OK.

Dialogue 2

A: Is that your umbrella? (taking one small step)

B:Yes, it is.

A:Are you using it? (taking another small step)

B:No, I’m not.

A:Can I borrow it? (taking a third small step)

B: Of course.

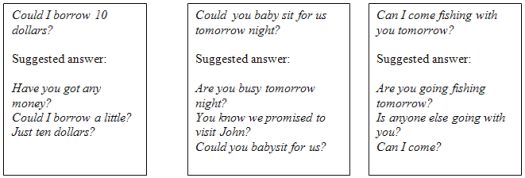

Students can practise breaking down requests into two or three questions. Students A and B stand two metres apart. A has a slip of paper with Can I borrow your umbrella? ( 3 steps) written on it. He has to break the request down into three questions, taking a small step towards B each time. Students change partners and practise with other requests, prepared on slips of paper. Other examples:

Could I borrow 10 dollars?

Suggested answer:

Have you got any money?

Could I borrow a little?

Just ten dollars?

|

Oh!often occurs with other discourse markers. It can show ‘pain, disappointment or surprise, or intense expression of feeling’ (p.115,116). Here are some suggested expressions with Oh! and meanings:

Oh dear!(sympathy), Oh no! (surprise/disappointment), Oh well! (resignation), Oh I see! (understanding), Oh my goodness! (shock/disbelief),Oh lovely! (happiness/approval)

Put students in groups. One person tells a story, others listen and score a point for each correct use of Oh!+interjection, (points can be awarded by the story teller, or taken off for wrong use.) Alternatively, the group cooperates to score points for the whole team.

Vague language is more likely to be the sign of a skilled and sensitive speaker than a lazy one (p.202), and therefore to be encouraged. Pass out some pictures around the class. When everyone has seen them, collect them back. Now, describe one of them to the class, but replace all nouns with stuff, thing(s) and bit(s). Example:

There’s some blue stuff with a white thing floating on it. The white thing is flat with a long thin bit on top. There’s nothing else except blue stuff and white bits behind.

Students have to listen carefully to visualize and remember the picture, in this case a description of a yacht, water, and cloudy sky. The person describing is focusing on adjectives, verbs and prepositions to get the meaning across.

In real time speech ‘utterances are linked… as if in a chain’ (p.168) rather than built into sentences. Thus, unless the students can learn to speak in phrasal chains, they will have a double disadvantage compared to native speakers, as they not only have fewer language resources but will be setting themselves the more difficult task of speaking in sentences.

Ask students to look at a picture and produce as many words as possible about it in a limited time, say 30 seconds. To stop them trying to create full sentences, only words in two, three and four word phrases are counted, and that the person who produces the most relevant words is the winner. This would encourage phrase volume, rather than complete sentences. Point out the types of phrases, e.g.: adjective+ noun(big park), noun+ and+ noun(mother and father), noun+ verb+ object(children playing tennis), participle/noun+ prepositional phrase (dog on the right, sleeping under a tree). Meaningless phrases such as sleep tree do not count, of course. Put students in groups, with judges to count the words.

As the features of spoken grammar are different from traditional grammar we need to adapt activities, and develop new ones if we want students to practise using the forms productively. The need for students to be able to use these forms will vary according to context, however, benefits may include: more natural sounding language, increased fluency, since they are imitating native speakers’ fluency strategies, and perhaps more enjoyment, as using spoken grammar can be a fun way of exploring language.

Carter, R. and M. McCarthy. 2006, Cambridge Grammar of English, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology for Teaching Spoken Grammar and English course at Pilgrims website.

|