My Lived Experience with the Communicative Approach to Language Teaching in China

Wei Liu, China

Wei Liu obtained his BA in English Education in July 1999. Due to the shortage of College English teachers as a result of the large scale university entrance expansion at the end of last century in China, he got a job teaching English to non-English majors in a university in Shenyang, the center of Northeastern China. At the end of 2000, he was transferred to teach in Shandong University at Weihai. He was admitted into a 3-year Masters program in 2003 in Shandong University (Jinan), studying English Linguistics and Language Acquisition. He got his MA in 2006. After that, he went back to Weihai to teach. In 2008, he was admitted into a PhD program in Beijing Normal University studying in Foreign Language Education and Teacher Education. He is doing research on Chinese secondary school teachers’ lived experience with the Communicative Approach to Language Teaching. He is affiliated with Shandong University at Weihai, and in the past three years, he has been working as a full-time PhD student in Beijing Normal University. E-mail: davidweihai@163.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Doubts cast over CLT and TBLT

Rectification of traditional Chinese methods

A self-study narrative of my own lived experience learning and teaching English in China

My pre-English learning experience

My English learning experience in secondary schools (1988-1995)

My English learning experience at university (1995-1999)

My first four years of teaching (1999-2003)

My MA study experience and post-MA teaching (2003-2008)

My ongoing PhD study (2008 onward)

Conclusions

This study is a retrospective narrative Self-Study on my own lived experience learning and teaching English in China. It is motivated by the on-going debate in China on the applicability of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) and its offshoot Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) in China. My pre-university non-communicative English learning experience was inhumanistic and ineffective in bringing about more comprehensive ability in English use. I benefited from a more communicative approach to language teaching both as a university student and as a teacher of English. However, as my own teaching experiences at different periods show, teachers have to teach in a way that is consistent with their beliefs and their prior experience, and is sensitive to their teaching contexts.

Self-Study as a new form of inquiry has won more recognition in the past two decades, with Self-Study studies appearing in journals like Teacher Education Quarterly and Teaching Education. In addition to being used as a way for the reflective professional development of the researcher, I believe Self-Study can also be used to shed light on more global issues by drawing on the lived experience of the researchers who are also learners and classroom teachers themselves.

My autobiographic Self-Study can serve as a response to the doubts cast over CLT in China and the effort to rectify traditional Chinese educational methods in recent journal articles. By doing a Self-Study Narrative like this, I also intend to show readers with my own lived experience how the communicative approach to language learning and teaching can benefit an EFL learner and teacher like myself.

The effectiveness of CLT, and its offshoot TBLT, has been constantly challenged in China. Some see CLT as incompatible with the traditional Chinese educational culture (e.g. Hu 2002; Sampson 1984); others see CLT as a Second Language methodology, and so not suitable in the English-as-a-foreign-language context in China (e.g. Bax 2003; Hammer 2007); still others see CLT as a sign of the Western post-colonialism and linguistic imperialism (e.g. Pennycook 1994, 1998; Phillipson 1992; Holliday 1994/2005). Last but not the least, CLT or any other method, is seen as irrelevant since we have entered the post-method era (e.g. Kumaravadivelu 2006).

Since CLT is the Chinese government’s stance (Liao 2004), some teachers have expressed their unhappiness with the imposition of CLT on them. In a narrative inquiry study, Tsui (2007) reported the frustrations experienced by a Chinese man called Minfang due to the imposition of CLT on him both as a student and as a teacher of English.

When he was at university studying English as a major, CLT was promoted in his university as a superior way of teaching and learning English. But he was skeptical about its effectiveness and appropriateness. He described CLT teaching style as “soft and unrealistic”. It was “soft” because the linguistic points were not made explicit in the communicative activities. Students could finish a host of activities without knowing how these activities were related to the language system and what was learned. It was “unrealistic” because it required the teacher to have pragmatic competence. He pointed out that most of his teachers had never interacted with native speakers of English, had never gone overseas, and had never found themselves in a situation where they had to use English for daily interaction. It was therefore unrealistic to expect them to evaluate the appropriateness of utterances and communication strategies. Moreover, he felt that these activities carried underlying cultural assumption which required students to assume different personae if they were to participate fully. For example, instantaneous oral participation in class required students to express opinions spontaneously without careful thinking. The nature of such communicative activities went against the Chinese culture, which attached a great deal of importance to making a thoughtful remarks and not babbling before one has thought things through.

Because of his disbelief in the value of communicative activities, he would do the very least for his CLT classes and spend most of his time learning in the traditional way. However, his high achievement in English was seen as a result of the communicative way of teaching and learning by the university. Also because of this high achievement in English, he was hired as a teacher in the same university upon his graduation. In his own teaching practice, he would still teach in the traditional way, and the students were happy. But again, due to the high score of students’ evaluation, he was given the title of the “Model CLT teacher” and was promoted to be the course leader of CLT. Even though he still did not believe in CLT, he could not publicly say so. He was very cautious about disclosing his true views about CLT. He was worried that he might be considered an outlaw by the authorities if he did that. As a result, he would teach communicatively in open classes observed by peer teachers or leaders, but teach in his own desired way in his close-door classes. He was disgusted by his “dual identity as a faked CLT practitioner and a real self [that] believed in eclecticism.”

He believed that CLT had been elevated as “a religion” in his institution rather than an approach to learning. He began to question whether there was such a thing as the most suitable methodology, be it CLT, task-based learning, or some other methodology. He felt that the teacher’s lived experience in the classroom was the best guide for pedagogical decision-making. He remarked, “My understanding now is that not matter what methodology you use, you have to be humanistic. The essence of CLT is humanism… I believe teaching is an integrated skill developed through experience, inspiration and passion.”

In my narrative, I will show the different experience I had with CLT. The differences between Minfang’s experience and my own experience are interesting in that we were both born in the mid 1970s, so we must have gone to universities at about the same time. We also both went to good universities famous for foreign language education, his in the very south of China and mine in the northeast of China.

At the same time as CLT has been challenged, efforts have been made to rectify traditional Chinese learning strategies and their use in English learning and teaching.

Gu (2003), for example, studied the vocabulary learning strategies of two successful EFL learners in China and concluded that repetition and memorization are very effective ways to learn vocabulary in the input-poor EFL environment in China. In a similar vein, Ding (2007) interviewed three university national prize-winning English majors in China and reported that text memorization and imitation were these three high achievers’ most effective methods of English learning.

Before I take a retrospective look at my own experience learning and teaching English in China, I feel it is necessary to first point out flaws in the conclusions of the Gu(2003) and Ding(2007)’s studies. Both Gu and Ding claim that traditional Chinese learning strategies, like repetition, memorization and imitation, are the ways in which the successful Chinese learners of English have achieved their superb mastery of English. However, a closer look at their articles will show that these learning methods are far from the complete picture of their successful English learning experience.

For example, Gu (2003) mentioned that one of his participants, Chi Wei, always aimed to be the best and believed that being able to speak was the most important goal in learning English (not only to pass the exams), so he went to the China-Canada Center privately to talk to someone in English, and he went to the English corner very often. He also mumbled to himself in English. While the other participant in the study, Chen Hua, enjoyed the beauty of English and immersed herself in English as if she was having a love affair with English. It strikes me that Chi Wei’s strategy of always trying to find opportunities to talk to people in English and Chen Hua’s immersion in English might be more important reasons for their language learning success than their repetition and memorization strategies used in vocabulary learning.

Similarly, in Ding (2007)’s study, text memorization and imitation might have played a role in contributing to these three students’ high achievement in English. However, whether it has played a major role is debatable. It was reported in the article that the three students all attended key foreign language high schools (schools that specialize in English education besides other subjects) before they took up English as their major at university and had many more hours of English instruction than their peers who attended regular high schools. Also mentioned in the article is the fact that the three students were required to recite English texts after school as homework, but at school they had discussions in English in small classes. Having discussions in English with a good teacher’ s guidance in a small class is a privilege not enjoyed by many high school students even in developed areas in China today. So the three students in the study all enjoyed English educational resources that the regular students in China can not enjoy. They had small classes, better facilities in high schools, more importantly, they had better teachers who could guide their discussions in English. They also attended extracurricular activities such as speech contests and drama in high school. The three students also reported that, at college, they learned more English outside class than inside class. Above all, they said they had native English speaking friends to talk to. The three students not only enjoyed elite educational resources and opportunities, they might also have better aptitude for language learning and they are very motivated learners. So I challenge the researcher’s attribution of their high achievement solely to their text memorization and imitation practice.

To reconcile CLT with traditional Chinese teaching methods, some scholars and practitioners have proposed an eclectic position on methodology use. Based on one study on Chinese college English majors’ opinions on both communicative and non-communicative activities, Rao (2002) concludes by saying:

“To update English teaching methods, EFL countries like China need to modernize, not westernize, English teaching; that is, to combine the ‘new’ with the ‘old’ to align the communicative approach with traditional teaching structures.”

However, eclecticism can be seen as a big basket that we can throw anything in without any scrutiny. As what Prabhu (1990) said:

“The eclectic view of methodology use often holds that there is some truth to every method. It makes common sense: If every method is a partial truth, then if we adopt different methods eclectively, we will be able to capture the whole truth. However, we often don’t know which method represents which part of the truth, or whether some methods overlap in representing part of the truth, and thus we don’t know which part of a certain method to be adopted in the eclectic blend.”

So in this sense, eclecticism is just too eclectic to be satisfactory and it is too easy a solution that it is not a solution at all.

In order to demonstrate that CLT can be fruitfully adopted to learn and teach English in China, and to demonstrate that CLT is needed in China to help students achieve the much needed communicative competence in English, I hope to share with readers my own experience of learning and teaching English in China.

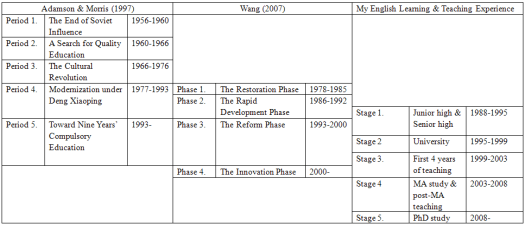

I divide my English learning and teaching experience into five stages. In order to provide a bigger context, I embed the narrative of my own lived experience within the historical development of English education during the same periods in China. The historical context of English education in China is provided by both Adamson & Morris (1997) and Wang (2001)’s periodizations of English education development in P.R.China (See Table 1).

I was born into a farmer’s family, the last of three children, in a remote, mountainous village in the northeast of China, known to the West as Manchuria. The year of my birth was 1975, one year before the death of Chairman Mao which marked the end of the Cultural Revolution, and three years before Deng Xiaoping started his Reform and Open-up in China.

During the Cultural Revolution, “most schools stopped teaching English. Many foreign-language teachers suffered at the hands of Red Guards after being accused of spying for other countries or worshiping everything foreign. Many experts on foreign language education had been dismissed from their posts and assigned menial jobs or sent to the countryside.”(Adamson & Morris, 1997)

As schools returned to normality after the Cultural Revolution, a new English syllabus was quickly produced in 1978, followed by accompanying textbooks. “The syllabus allowed two beginning levels, one from Primary 3, the other from Junior Secondary 1. As there were not enough teachers at that time, the actual offering of English in almost all the schools began from junior secondary school.”(Wang, 2007) Due to this reason, like most people of my age in China, I did not begin to learn English until when I entered junior middle school in 1988.

The Chinese Nine-Year Compulsory Education Law was officially passed in 1986, but it was not yet implemented in where I was from in 1988. So we had to take an entrance exam which selected top student to enter the junior middle school. There were 18 students from my village primary school who took the exam, and only 7 passed and were admitted to the only junior middle school in the township. I was one of the 7 lucky ones.

When I entered junior middle school and began to learn English in 1988, English education in China was already 2 years on into the Fast Development Phase (1986-1993) (Wang, 2007), following the issue of another English syllabus in 1986. In line with the Open Up policy, the 1986 syllabus states that “English does not only have instrumental utility, but more importantly, communicative and educational values…teaching should focus more on the students’ ability to use the language.” (Wang, 2007) The pedagogical approach in the textbooks we used was a blend of audiolingualism and grammar-translation method, with dialogues and sentence patterns for oral drilling gradually giving way to more reading passages (Adamson & Morris, 1997).

As for the English classes in my junior middle school (1988-1991) as I reflect on them, even the audiolingual method was not much used. I remember reading the vocabulary, the dialogues and sentences after the teacher. And we would also read aloud the dialogues according to different roles in the dialogues. The teacher was the only oral language input we had, because we never listened to the recordings on the tape. There was no tape recorder available. Of course, the teacher would explain how different grammatical items and sentence structures worked. In addition to all these, we were supposed to recite all the dialogues and reading passages on the book. Reading and memorizing the textbooks seems to be the major thing we did most of the time. Such practice carried on when I got to senior middle school.

I was in senior middle school from 1991 to 1995. I took the university entrance exam twice in 1994 and 1995, due to my failure to enter into a desired university at the first attempt. When I was in senior middle school, the 1986 national English syllabus was revised in 1993. In the 1993 syllabus, the word communication was used in the objectives of teaching for the first time (Wang, 2007). To achieve this end, the teachers were advised by the curriculum to use a variety of teaching strategies to create situations for promoting communicative competence: “Language form has to be combined with its meaning and with what the students think and want to say. Special attention should be paid to turning the language skills acquired through practice into the capacity of using the language for the purpose of communication...” (Adamson & Morris, 1997)

However, the newly revised curriculum did not apply to us who were about to graduate from high school. And the new curriculum ideas did not seem to have any impact on the English learning and teaching practice in my county high school either. Teachers continued to explain the reading texts and grammar items in Chinese. We continued to recite the reading passages in the textbooks. There were no dialogues in the textbooks. The new textbooks that accompanied the 1993 curriculum, “Junior English for China” (JEFC) and “Senior English for China” (SEFC) jointly written by People’s Education Press (PEP) and Longman were used after I finished high school.

Many students of my age can remember or can still recite the first reading text in the first lesson of the first book we used in senior high “How Marx Learned Foreign Languages”. In the final paragraph it says:

“In one of his books, Marx gave some advice on how to learn a foreign language. He said, when people are learning a foreign language, they should not translate everything into their own language. If they do this, it shows they have not mastered it. When they use the foreign language, they should try to forget all about their own. If they cannot do this, they have not really learned the spirit of the foreign language and cannot use it freely.”

Clearly Karl Marx’s advice on foreign language study was not well accepted. Translation and grammar explanation in Chinese loomed large in my high school English teaching. In addition, we did uncountable model test papers followed by the teachers’ minute explanation about each grammar item tested. Of course, at that time I was not able to scrutinize the teachers’ teaching methodology as I do now. I was not aware that there were other ways to teach and learn English. I was not aware either that literacy in a foreign language was not the only goal of foreign language learning. I never thought I was expected to speak English and understand English when people speak it to me. My experience of learning English before university in a way deceived me into believing that my English was good. This is because I scored high in various written English tests. Speaking and listening skills were not tested in the exams back then. The illusion of being a good English learner led me to decide to learn English as a major at university. However, this illusion shattered bitterly when I first got to university and found that I could not understand much of what the teachers were saying in English in class!

I entered into a university famous for foreign language education in the northeast of China at my second attempt at the Gaokao (the national university entrance exam) in 1995. However, my excitement was soon replaced by a strong sense of shame and regret.

I will never forget the first English class I had. The teacher hoped to evaluate how well we could understand English, so she gave us a small dictation test. She played a tape on the cassette player and asked us to take down anything we could hear. I guess it was a short story read in a very slow pace. But I can only guess because I did not understand a thing. All I could hear and take down were the articles at the beginning of some sentences- “The”, “A”. There were 20 students in my class, and I was the only boy. I looked around and saw that the girls around me, especially those from cities, were taking down complete sentences though occasionally missing a few words. The quality of English education must have been better in the cities. At that moment I felt totally ashamed and out of place. I felt it was the biggest mistake that I ever made to study English as a major at university. If I could, I would change my major without a doubt.

I realized soon that I did not have the luxury to regret choosing the wrong major any more, because I knew there was nothing I could do but stick to it. But a sense of shame was always with me. It was a university specialized in foreign language education, so everybody was supposed to speak beautiful English. Those who did so were admired, and those who did not were laughed at. My self-efficacy and self-esteem were given still another huge blow at the end of the first semester. I was among the only five students of the whole grade (about 120 in total) who flunked the speaking test for the first semester.

In retrospect, my first two years at university was unhappy or even painful. For the two years, English study was not fun but a pure struggle to survive. I was making painstaking efforts to catch up. In class, all the teachers spoke all in English. They refused to speak Chinese even though some of us could not totally understand. The teacher for our speaking class for the first semester was a lady who spoke very fast English. I was amazed by how she got so fluent in English. At the end of the semester, she invited us to reflect on our achievement in the first semester. She asked us whether we thought we had made process, and we all shook our heads and said no. But she said we had because when she first talked to us in English at the beginning of that semester, we had great difficulty following her, but at the end of the semester, we could understand everything she said. We had to agree. The target-language-only classes certainly helped my listening skills. But I found my oral skills much harder to improve.

The teachers used a lot of pair-work and group-work activities in class to engage us in using the language. There were also a lot of discussions and debates in English in class where I always played the devil’s advocate purposefully holding different views from most of the girls. The university also held big English corners twice a week in the evenings attracting both students on campus and people who were already working. I would always go.

A big change in my English learning experience took place in the third year where I began to gain self-efficacy as an English learner and began to enjoy learning English. I signed up for a selective African American Literature class taught by an exchange professor from the U.S. She was an outstanding African American lady in her 60s. Her husband was retired from a car insurance company, and he was with her in China. Gradually I became a very good friend to the couple. I gave them a lot of help with their life in China and very naturally I talked to them much in English.

My interactions with them gave me some real experience of using English for real communicative purposes. I also gained much confidence in my oral ability because I could make myself understood even though I was aware that my grammar was not always correct. More importantly, I gradually improved my accuracy and fluency in English through my interaction with them over the one year they were in China. In addition, they were interested in China and always asked me about China. So I had to do a lot of thinking in English so that I could talk to them about China. Over time, I developed a habit of thinking in English, constantly challenging myself to express complex ideas in English. I remember, when I was sitting in the class of a general education course in Chinese, I was thinking to myself whether I could talk about those things discussed in the course in English.

In the 4th year, I began to feel a sense of achievement in my English study. I felt much more confident in speaking English in public. I had not only caught up on my pronunciation and intonation, I was also able to express more complicated thoughts in English. In an advanced writing class, my essays were often chosen by the teacher to read in class. I also chose to be supervised by another American exchange professor in writing my graduation thesis. I got an A for it.

My English learning experience before university shows that traditional Chinese learning strategies such as memorization and imitation by themselves are not sufficient ways to achieve more comprehensive communicative competence in a foreign language. The teacher-centered Grammar Translation method predominantly used at that time is characterized by “an emphasis on reading and writing skills, constant references to the learners' mother tongue, a focus on grammatical forms, and memorization of grammatical paradigms” (Adamson & Morris, 1997). It was effective in training students’ literacy skills in a foreign language, but was not helpful to the development of conversational skills. In contrast to my secondary schooling experience, my university experience serves to suggest that it is important for students to engage in extensive communicative use of the target language if high oral interactive ability in the language is aimed at. Opportunities to use the language will trigger deep cognitive processing of the language, resulting in more accurate, fluent and complex performance in the language.

In 1999 I graduated from university. In the same year, a new educational policy was introduced in China which changed the landscape of Chinese higher education. The policy is known to Chinese people as the Expansion of University Enrollment. The policy aims to gradually increase the university enrollment rate in China to 15% by 2010. In 1999 alone, university enrollment increased 48% nation wide from 1.08 million in 1998 to 1.59 million in 1999. Since every university student has to take English for at least four semesters, the expansion of university enrollment created a huge demand for College English (CE, i.e. English for non-English majors at universities) teachers. For this reason, I got a job as a CE teacher at a university upon graduation only with a B.A. in hand. The university was located in Shenyang, the biggest city in the northeast. One year later, I transferred to work in another university in a coastal city in Shandong, Confucius’s home province.

The most prevalent teaching method used in CE teaching was the Intensive Reading Approach (IRA), a result of prior Soviet influence. In a typical reading class, the teacher would first guide the students in reading and explaining the new vocabulary one by one in Chinese, occasionally giving examples to show the usage of some words. Secondly, the teacher would read with students the reading passage sentence by sentence, translating them into Chinese and explaining grammar items and structures in Chinese. Thirdly, the teacher would do the exercises after the reading text with students to consolidate the learning of grammatical items and vocabulary covered in the lesson.

I did not challenge this common practice and I did not know how, but I tried to incorporate the target-language-only style of teaching I experienced at university into my own teaching. That is, I tried to teach only in English. I would do what most other teachers were doing (as I described above), but I did them in English only. To be more specific, I would explain the meanings and usages of vocabulary in English. I would not translate the reading texts, but I paraphrased them also sentence by sentence. Even when I dealt with the exercises in the book, I spoke only English. It was still very much teacher-centered, textbook-driven, exam-oriented teaching, but I could at least engage my students in active listening to the language. In reflection, my teaching practice at my initial teaching career subconsciously followed Krashen (1985)’s Input Hypothesis which claims that learners’ extensive exposure to the comprehensible L2 input is the foundation for L2 acquisition. It was also in line with Cook (1996)’s Informational Communicative Style of teaching which engages learners in perceiving and processing information in the target language. My students liked my classes and they enjoyed listening to and responding to me in English.

My desire to conduct monolingual classes in English pushed me to think in English. Basically I hoped to be able to express all my thoughts in English, like a native speaker of English. For this reason, I chose only to read in English and to watch English TV and movies. I also tried to hang out more with my native English speaking colleagues to learn more idiomatic English. I was also thinking about whether I could possibly raise my future child in English. Thinking and speaking English had become a very important part of my life. As a result, my overall English proficiency had greatly improved. I became much more confident with speaking English in life and in class.

One argument against the use of more communicative way of English in China is that many Chinese English teachers do not speak enough English to handle uncharted communication in English in a communicative class. But my experience seems to suggest that only when teachers force themselves to express complex thoughts in English can they improve their proficiency in English. CLT might be able to serve as an in-service training tool for teachers to improve their target language skills.

From 2003 to 2006, I took three years off my teaching to study my Masters in English Linguistics in the capital city of Shandong. During the three years, I was exposed to different schools of linguistics, and I took particular interest in Chomsky’s ideas of people’s innate faculty for language acquisition and the critical age for its access. I was also exposed to different Second Language Acquisition theories, such as Krashen’s Input Hypotheses and Swain’s Output Hypothesis. More importantly, I read books on language teaching such as the history of language teaching methodology and CLT /TBLT (Task-Based Language Teaching) in particular. I also carried my previous question into my MA study: whether I could raise my future child bilingually both in Chinese and English. I actively searched for theories and practices of bilingual education, especially information concerning the possibility of bilingual parenting in a foreign language, nonnative to either parent. I ended up writing my MA thesis on the very topic.

In 2006 after I obtained my Masters Degree, I left the CE department and was transferred to teach English majors in the English department. I taught two courses. One course was Comprehensive English for sophomore students. Comprehensive English was considered the most important course for English major students with six contact hours a week. The other course was English Teaching Methodology, a selective course that had been written in the curriculum but was never offered to students. It was offered to 3rd year English majors who wanted to consider teaching as one of their future career options.

In the Comprehensive English course, I tried to teach more communicatively, using what I had learned in graduate school. I stopped dealing with the vocabulary in class, which students were supposed to do before class. I also stopped covering the reading texts sentence by sentence. Instead, I designed questions based on the text and engaged students in doing more in-depth discussions on the meanings. I also introduced other tasks to involve students in having more meaningful use of the language. For example, knowing that students were from different parts of China, I invited them to prepare presentations to introduce their hometown cultures and tourist attractions in English. I also encouraged them to do creative writing in English, and I put all their writings in a book to circulate in the class. I also actively looked for opportunities after class for them to use their English. I once paired my students up with a group of American university students who were on my campus for Chinese summer school. I occasionally brought native English speaker friends to my class to talk to my students. I also tried to find internship opportunities for my students to work in foreign investment companies through my own connections.

Since what I did in class was different from what they were used to, some students once questioned my teaching. They wondered whether I was doing the right thing, whether I was being irresponsible when I did not follow the book closely. But after seeing my efforts at helping them find opportunities to use their English, they understood that I was not being irresponsible, instead, I was truly concerned with their development as communicative and creative users of the language.

In my English Teaching Methodology course, I assumed a new role, a teacher educator, for the prospective English teachers who signed up for the course. And the number of the students who signed up for the course amazed me. The first semester I offered the course, 76 students signed up. The second semester I taught it, 128 students signed up. I never knew that so many of them would consider teaching as a career option since the university was not a teacher training university. And what was frightening to me was, if they ended up teaching in the future, the course I taught was the only training they could possibly get before they entered their own classrooms! I felt the burden on me and I felt the need to get more training myself to be a better EFL (English as a Foreign Language) teacher educator.

In the summer of 2007, I was involved in a short in-service training program for senior middle school English teachers in my city. I was asked to conduct a four-hour seminar on CLT / TBLT for over 100 teachers. I first introduced the development of the language teaching theories in the West which naturally led to CLT/TBLT. I then invited them to discuss whether CLT/TBLT could be implemented in their own classrooms. To my surprise, many of them said no. I was surprised because it was four years since the new National English Curriculum Standards (NECS) for senior middle school (2003) was issued, which advocated “student-centered and Task-based teaching” (Wang, 2007). And Shandong province was one of the first provinces to have participated in the piloting of the new curriculum innovation since 2004. In the NECS, the goal of English learning and teaching was postulated as the “comprehensive ability in language use”. To achieve this goal, teachers are supposed to change the teacher-centered, textbook-centered, knowledge transmission mode of classroom teaching. But how come many of these teachers still did not believe CLT/TBLT could be used in their classes? Were they just lazy and did not want to do the right thing? How could I make them teach more communicatively?

I entered the current PhD program in 2008. As I was preparing for the PhD entrance exam, I read some books that changed my views. First, the value of teaching method as a theoretical construct in language teaching has been suspected, as Kumaravadivelu (2006) writes:

“…established methods are founded on idealized concepts geared toward idealized contexts. And, as such, they are far removed from classroom reality. Because learning and teaching needs, wants, and situations are unpredictably numerous, no idealized method can visualize all the variables in advance in order to provide context-specific solutions that practicing teachers badly need in order to tackle the challenges they confront every day of their professional lives”. (p.165)

Second, teaching methods are perceived as representing the old fashioned approach to Second Language Teacher Education (SLTE) prevalent in the 1970s and 1980s (Richards, 1998), for example, both CLT and TBLT reflect the top-down, prescriptive approach to SLTE which posits teachers as passive recipients and implementers of externally made decisions. The method-based model of teaching fails to reflect the new understanding of teacher education which sees the need to move “beyond training” (Richards, 1998) and to embrace a more bottom-up, discovery-based approach to teacher education.

Thirdly, my previous attitude to teachers’ uptake of teaching methodologies represented a fidelity view on curriculum implementation (Snyder, Bolin and Zumwalt 1992), which measures the degree to which a particular innovation is implemented as planned, and to identify the factors that facilitate or hinder implementation as planned. Such an approach to curriculum research has its limitations as there is always a gap between curriculum rhetoric and pedagogical reality (Nunan, 2003). On the other end of the extremity is the enactment perspective on curriculum, which sees the teacher as a curriculum developer and the curriculum as the teacher’s personal construct (Snyder, Bolin and Zumwalt 1992). This view also has its limitations as it renders the state curriculum planning totally irrelevant. Lying between the two extremes is the mutual adaptation approach, which focuses on the interaction and adaptation between teachers and the curriculum (Snyder, Bolin and Zumwalt 1992).

After I entered the PhD program, I did more reading and made more contacts with secondary school teachers. I came to understand more about the pressure and the contextual constraints they had to face in their work. As a result, I feel very intensely that the mutual adaptation approach is the most reasonable approach to studying the relationship between the teachers’ work and the planned curriculum, as it allows teachers to dialogue with the planned curriculum, negotiate with the planned curriculum and adapt the planned curriculum according to the individual environments so that they can adopt the most appropriate pedagogy to suit their local practice (Snyder, Bolin and Zumwalt 1992).

My pre-university non-communicative English learning experience equipped me with good literacy skills in English, and my success in written English tests gave me a false impression that I was a good English learner. That impression deceived me into taking English as my major at university. The expectation of high listening and oral proficiency in English at university made me suffer great pain in my initial catch-up effort. However, the English-only classes quickly improved my listening skills, and opportunities to use English both in and outside classroom helped me catch up on my conversational proficiency in English.

In my teaching career, my effort to teach communicatively benefited both students’ and my own ability in using English. However, though I benefited from a more communicative approach to language teaching both as a student and as a teacher, I realized that it is inappropriate to impose it on other teachers. As my own teaching experiences show, I was using different versions of CLT at different periods. Teachers have to teach in a way that is consistent with their beliefs and their prior experience, and is sensitive to their teaching contexts. What we can do is study the exigencies of teachers’ teaching in their own contexts so that we can know how to help them move toward a more desirable approach to teaching in line with students’ needs and the needs of the society.

Table 1. The Development of English Education in P. R. China and My Own Experience

Adamson, B. & Morris, P. (1997) The English Curriculum in the People's

Republic of China Comparative Education Review, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 3-26

Bax, S. 2003. ‘The End of CLT: a context approach to language teaching’. ELT Journal Vol.57/3

Cook,V. 1996. Second Language Learning and Language Teaching. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press

Ding, Y. 2007. Text memorization and imitation: The practices of successful Chinese learners of English. System 35:271-280

Gu, P.Y. 2003. Fine Brush and Freehand: The Vocabulary-Learning Art of Two Successful Chinese EFL learners. TESEL Quarterly, Vol, 37, No.1:73-104

Harmer, J. 2007. The Practice of English Language Teaching (fourth edition) Pearson Longman

Holliday, A. 1994. Appropriate Methodology and Social Context. Cambridge University Press.

Holliday, A. 2005. The Struggle to Teach English as an International Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Hu, G, 2002. ‘Potential cultural resistance to pedagogical imports: the case of Communicative Language Teaching in China’. Language, Culture and Curriculum. Vol.15, No2.

Krashen, S. 1985. The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. London: Longman

Kumaravadivelu, B. 2006. ‘TESOL methods: changing tracks, challenging trends.’ TESOL Quarterly 40, 59-81

Liao,X. 2004. ‘The need for Communicative Language Teaching in China’. ELT Journal 58/3: 270-3

National English curriculum standards for senior secondary school (Piloting Edition). (2003). Beijing: People’s Education Press.

Nunan.D. 2003. The Impact of English as a Global Language on Educational Policies and Practices in the Asia-Pacific Region. TESOL QUARTERLY Vol. 37(4)

Pennycook, A. 1994 The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language. London: Longman.

Penneycook, A. 1998. English and the Discourse of Colonialism. London: Routledge.

Phillipson, R. 1992. Linguistic Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Prubhu, N.S. 1990. ‘There is no best method-why?’ TESOL Quarterly 24/2: 161-72

Rao, Z. 2002. Chinese students’ perceptions of communicative and non-communicative activities in EFL classroom. System 30:85-105

Richards, J.C. 1998. Beyond Training. Cambridge University Press

Sampson, G..P. 1984: ‘Exporting language teaching methods from Canada to China’. TESL Canada Journal 1(1)

Snyder, J., Bolin, F., & Zumwalt, K. (1992). Curriculum implementation. In P. W.

Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Curriculum (pp. 402-435). New York: Macmillan.

Tsui, A. B.M. 2007. ‘Complexities of Identity Formation: A Narrative Inquiry of an EFL Teacher’. TESOL Quarterly Vol. 41, No. 4.

Wang, Q. 2007. The National Curriculum Changes and Their Effects on ELT in the People’s Republic of China, edited by J. Cummins and C. Davison, The International Handbook of English Language Teaching (Vol.1), Norwell, Massachusetts: Springer Publications.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|