Game-based Immersive Approach to EFL and CLIL: A Case Example

Letizia Cinganotto, Italy

Letizia Cinganotto, PhD, is a researcher at the Italian Institute for Documentation, Innovation, Educational Research (INDIRE), Italy. She is a former teacher of English, teacher trainer and author of digital contents. She worked for several years at the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research, dealing with issues relating to the Upper Secondary School Reform, with particular focus on foreign languages and on CLIL. She has presented papers at national and international conferences and published articles and papers in national and international peer-reviewed journals. Her main research interests are: EFL, CLIL, CALL (Computer Assisted Language Learning), TELL (Technology Enhanced Language Learning). Email: l.cinganotto@indire.it

Menu

Abstract

Background

Language learning and CLIL in Italy

First initiatives

The research question

The structure of the methodological course

What the participants think about immersive English teaching

The “English Village” community

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

This paper presents a case example related to a project promoted by INDIRE, the Italian Institute for Documentation, Innovation and Educational Research, in cooperation with a network of international experts in EFL and immersive teaching. The Institute created a virtual world, called “EdMondo”, which is addressed only to education, involving teachers and students from all over Italy. The virtual approach in combination with gamification can represent an effective way to enhance the teaching/learning of a foreign language and the delivery of subject content through a foreign language as in CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) methodology. INDIRE started to experiment the potential of virtual worlds for language teaching and learning in 2012. This paper illustrates a training initiative in which a group of teachers, in cooperation with INDIRE researchers, were engaged in training paths aimed at improving their methodological competences related to the use of immersive game-based technologies for EFL or CLIL lessons. The main focus of the paper is the description of the project and its main outcomes, with particular attention to the teachers’ reactions and to their challenges to build, design and script games for English or CLIL lessons in a virtual world. Some insights about the background on immersive and game-based learning are also provided.

Game-based immersive teaching and learning in virtual worlds has been recognized as an effective way to engage both teachers and students in new challenging and interactive experiences, with a huge potential in terms of learning outcomes (Felix, 2005; de Freitas, 2008; Whitton & Hollins, P, 2008; Kapp, 2012).

Game-based learning was recognized by the European Commission as an important dimension of CALL (Computer Assisted Language Learning), pointing out its potential with reference to CLIL and to language learning in general (European Commission, 2014).

In particular, the following options are mentioned as examples of CALL:

- Authentic foreign language material, such as video clips, flash-animations, web-quests, pod-casts, web-casts, news broadcasts etc.;

- Online environments where learners can communicate with foreign language speakers, through email, text-based computer-mediated communication (synchronous and asynchronous), social media, or voice/video conferencing;

- Language-learning tools (online apps or software), for phonetics, pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar and clause analysis, which may include a text-to-speech function or speech recognition, and often include interactive and guided exercises;

- Online proprietary virtual learning environments, which offer teacher-student and peer-to- peer communication;

- Game-based learning.

Games are becoming a focal point for the development of new learning adventures, with an improvement in the attainment of learning objectives when compared to students using standard instructional methods. Games create deeper learning experiences that engage and motivate learners much more than with traditional teaching methodologies, especially when a foreign language is involved: in this case communication takes place in a context which can take the shape of life-like situations (Dickey, 2005; Vickers, 2007). In fact game-based learning refers to the borrowing of certain game principles and applying them to real-life settings to engage users (Trybus, 2015).

The 2014 NMC Horizon Report (www.nmc.org/pdf/2014-nmc-horizon-report-he-EN.pdf) mentions games and gamification as a trend in higher education with an adoption timeframe of two to three years, specifying that 68% of players are over 18 years old, university age. If game-based learning is effective at university age, it is easy to understand how much better it can work with younger students attending primary or secondary school (Mawer & Stanley, 2011; Farr & Murray, 2016). Gamification helps create a system that enables learners to rehearse real-life scenarios and challenges in a safe environment. Many are the benefits a learner can get from a game-based learning experience, such as the following:

- engaging friendly competition

- giving the learners a sense of achievement

- offering an engaging and challenging learning experience

- encouraging learners to progress through the content and motivate action

- giving learners an immediate feedback and suggest a behavioural change

- helping higher recall and retention.

James Paul Gee describes some of the learning principles inspiring gamification, such as the opportunity to experience the world through new roles and identities and the potential to encourage reflective practice through a cycle of probing, hypothesizing, probing again, and rethinking strategies (Gee, 2003). Gee suggests: “good videogames incorporate good learning principles, principles supported by current research in cognitive science” (Gee, 2005).

The Italian Ministry of Education strongly believes in the development of teachers’ and students’ language competences.

As for students, the Ministry reached the important goal to set standards for the target level of competence in the first foreign language: A1 CEFR for students at the end of primary school; A2 for students at the end of lower secondary school; B2 at the end of upper secondary school.

As far as teachers are concerned, the Ministry is investing a great deal in teacher training, both at primary and secondary level, especially considering the latest Reform Law named “The Good School” (“La Buona Scuola”), Law 107/2015, which has made continuous professional development for teachers mandatory, including language learning and CLIL.

Virtual worlds can represent an alternative and attractive way to promote teacher training and as a consequence to get better student learning outcomes and a higher level of competence in the foreign language.

That is why INDIRE, which has always cooperated with the Italian Ministry of Education, having as part of its mission, the organization and the support of teacher training pathways, has decided to start experimenting a virtual world (EdMondo), addressed to Italian schools, engaging in different projects, among which a game-based approach to teacher training for English and CLIL.

The first steps with language teaching and CLIL in EdMondo were taken in 2011, within a national project promoted by the Italian Ministry of Education, named “E-CLIL”, involving a network of schools all over Italy, aiming to encourage teachers to implement CLIL lessons in their classes with the use of ICT and web tools. One of the teachers taking part in the project (Maurizio Bracardi, http://www.mabra.it/clil/), decided to work in EdMondo with his students building labs in the virtual world and let them do chemistry experiments there. His work was mentioned as an example of best practice for the “E-CLIL” project (Langé & Cinganotto, 2014).

Another experimental project was carried out in 2012, within a postgraduate course delivered by IUL, the online University co-founded and co-financed by INDIRE and Florence University, addressed to language teachers, named “Languages on the net”: teachers were guided to explore the potential of ICT for language learning. Within this course, some lessons were carried out in EdMondo and the teachers found a completely new world and a new way to design their lessons: they discovered how EdMondo could recreate life-like contexts for meaningful communication and interaction, especially if based on a game perspective.

Then, in 2015 INDIRE decided to devote a specific research project on teaching and learning English or content in English through a game-based immersive approach, also taking advantage of a renowned international network of experts in virtual worlds and English teaching.

Figure 1: A training pilot project in EdMondo

The research project stemmed from the following research question: “Can virtual worlds and game-based immersive technologies and approach enhance the teaching and learning of English and the delivery of content in English (CLIL)?”

The initiative consisted of a specific training pathway for teachers designed as a methodological course on immersive English teaching in “EdMondo”, based on practical teaching activities and games. A specific land, called “English Village” was created to work and play in English and to collect all the games created by the teachers.

INDIRE researchers (the author of this contribution in cooperation with Andrea Benassi) (Benassi, 2012; Benassi, Cinganotto, 2015) were engaged in investigating the impact of virtual worlds and game-based immersive technologies in improving teaching strategies and language competences by using different research methods and by collecting the participants’ feedback through the use of questionnaires, portfolios, diaries, etc.

Figure 2: A typical lesson in English Village

The training course was planned as a five-module pathway (two weeks for each module), with weekly meetings in English Village, moderated by international experts and asynchronous meetings and activities on a Moodle platform. The well-known experts (Carol Rainbow, An Novack, Shelwyn Carregan, Barbara Mac Queen, Doris Molero) were coordinated by a renowned teacher, teacher trainer, EFL and immersive teaching expert: Heike Philp.

Weekly badges after the accomplishment of certain tasks and the final certificate of attendance were aimed at making it a real and institutional teacher training pathway.

The target was made up of teachers from any school level (primary, lower or upper secondary school), preferably English teachers but all subject teachers were welcome, especially CLIL teachers.

These were the objectives of the course:

- Designing and creating language games in EdMondo

- Creating interactive objects with scripts, sound, and images

- Planning and implementing English or CLIL lessons in EdMondo

- Creating engaging learning environments and simulations

- Conceiving a lesson plan and a rationale for a game or a simulation.

This was the syllabus of the course:

Module 1 - Working with images

During the first module teachers were guided through exploring various games and learning how to build a board game.

Module 2 - Working with sounds

Designing a CLIL/English lesson using objects with sounds, according to their school level.

Module 3- Working with objects

Designing a CLIL/English lesson using some of the objects of this module.

Module 4 - Adding game design to language learning activities

Designing a CLIL/English lesson using a game environment.

Module 5 - Global simulation

Therefore the participants were guided to discover the use of Interactive Scenarios, Global Simulations and Role-Play Games applied in Virtual Environments for a foreign language or a CLIL class: students feel immersed in a story they construct with other participants through the representation of a fictitious character they choose to be (Bailenson, 2006; Childress et al., 2006).

Each module was structured with a “Show and Tell” week, moderated by an international expert delivering explanations, tutorials, examples etc. on how to build games, scenarios etc. and a “Hands on” week, where the participants created their own games and products to be described during the synchronous meeting inworld. Particular attention was devoted to the didactic aspect of the games, as teachers were invited to plan an EFL lesson or a CLIL lesson providing the use of the specific game/scenario/simulation they had created, according to their school level.

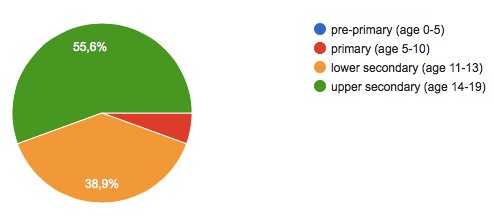

An initial survey provided the necessary data about the participants, as shown below:

Figure 3: School level of the teachers

Below there are some answers the participants gave to the question from the survey: “What do you think about game-based immersive English teaching?”

It is really realistic.

I've been experiencing immersive world since 2007 and I learnt very much because immersive environments enrich creativity, they are a great way to guide people to solve problems and they give opportunities to improve their own competences.

I think this is a good method for me understanding English language.

Students' embodiment.

It's really motivating and involving and can give students the chance to exploit innovative learning environments.

The benefits consist in the chance to perform role plays in virtual world which are very similar to real life.

Unlike traditional learning technologies, Immersive Education is designed to engage students in the same way that today's best video games grab and keep the attention of players. This is a way near their world.

More creativity, enthusiasm and complicity with students in my opinion the immersive teaching develops the 5 senses.

Involvement, immersive environment and high student motivation.

In order to get the weekly badges and the final certificate, teachers were asked to work regularly on the Moodle platform, uploading content, lesson plans, commenting on their peers’ posts, interacting in the forum, uploading screenshots of their games or scenarios.

The peer assessment approach was a very important aspect of the initiative, as teachers were encouraged to give feedback to each other and mutually help in the accomplishment of the different tasks and during the process of game building inworld. Getting help from their peers turned out to be a very useful aspect for the participants, lowering their anxiety for a good performance for the teacher.

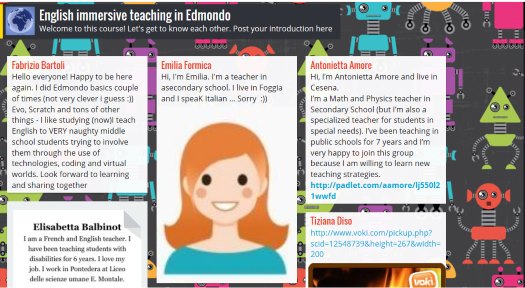

A great community of peers was created, as the padlet (a web tool allowing to post comments, pictures and videos on a digital board) below shows:

Figure 4: The padlet of the community

The community also interacted a great deal in the Facebook group devoted to English Village: they could ask for clarification and help each other in an informal way.

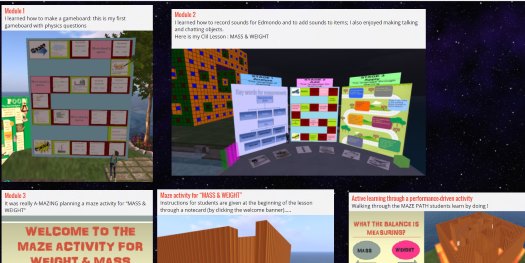

In order to help teachers reflect on the outcomes of their learning paths, they were encouraged to create their own learning diary, as a collection of their memories from the course which could be relevant for their personal and professional growth.

Diaries are wonderful examples of the outstanding results teachers achieved in terms of technical, digital, communicative, interpersonal and transversal competences.

Below there is an example of a learning diary collecting the screenshots of the games created during the different modules, commented and described by one of the teachers (Antonietta Amore).

Figure 5: An example of learning diary

The project was monitored by recording the lessons in EdMondo and collecting the teachers’ reactions through the use of different tools, such as the initial and final survey, the learning diary, the forum interactions.

A final festival took place in EdMondo at the end of the course: a live meeting with all the teachers presenting their games and products in EdMondo and getting their virtual certificate, together with the real one. A very impressive video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V7SUG4KXFts) was realized by Heike Philp to collect some of the most significant memories from the course and it was presented in Padua (Italy) last June during the 6th European summit on immersive education, IED (Benassi, Cinganotto, 2016; Cinganotto, Benassi, Philp, 2016).

The results are encouraging and rewarding: the teachers like interacting in EdMondo with their peers for their professional development and have started working in EdMondo with their students.

They think EdMondo may be a good environment for enriching training experience and for creative and challenging English and CLIL lessons.

Here are some of the teachers' comments collected through the final survey:

I have learnt new opportunities for virtual teaching.

I learnt how to use more the immersive teaching and I put in contact myself with gamification.

I'm very satisfied with this course. I've got a lot of inputs for teaching in RL and VL. Many thanks to all the trainers.

I have learnt what I was supposed to learn for each module. I can't build in EdMondo yet but I want to improve my skills.

I've understood better the possibilities that immersive methodology offers when dealing with English language learning. I've met very competent teachers and friendly colleagues... it's been really involving and motivating, even if I had to work hard in order to catch up with all the activities.

I learnt how to use immersive methodology, how to build learning tools and how to create interactive language pathways.

I improved my English.

The author is grateful to Andrea Benassi; Heike Philp and the network of international experts; Daniela Cuccurullo and Annie Mazzocco.

Bailenson, N.J., Yee, N., Merget, D. & Shroeder, R., (2006) The effect of behavioural realism and form realism of real-time avatar faces on verbal disclosure, nonverbal disclosure, emotion recognition, and copresence in dyadic interaction. Presence. 15(4):359-372.

Benassi, A., (2012) Virtual Story-telling. Metodi e tecniche di scrittura audiovisiva con i Mondi Virtuali. Tecnologie Didattiche n. 56: Volume 20, Numero 2.

Indice: http://www.tdmagazine.itd.cnr.it/journals/view/56.

Benassi, A., Cinganotto, L. (2015). EdMondo: Immersive Teaching/Learning Experiences in Italy. EDEN 2015 Conference, Barcelona, 9-12 Giugno 2015.

Benassi, A., Cinganotto, L., (2016), EdMondo –The Virtual World tailored for School, Conference Proceedings: IED (Immersive Education), 6th European Immersive Education Summit, Padua, Italy, 21-23 June 2016.

Cinganotto, L., Benassi A., Philp H., (2016), Learning and Teaching English in virtual worlds:

EdMondo, a case study from Italy, Conference Proceedings: IED (Immersive Education), 6th European Immersive Education Summit, Padua, Italy, 21-23 June 2016.

Childress, D.M. and Braswell, R., (2006) Using massively multiplayer online role-playing games for online learning, Distance Education. 27(2):187-196.

de Freitas, S., (2008) Emerging trends in serious games and virtual worlds, Emerging technologies for learning. (3).

Dickey, D.M. (2005), Three-dimensional virtual worlds and distance learning: two case studies of active worlds as a medium for distance education, British Journal of Education- al Technology.36 (3):439-451.

European Commission, (2014) Improving the effectiveness of language learning: CLIL and Computer Assisted Language Learning.

Farr F., Murray L., (2016) The Routledge Handbook of Language Learning and Technology, Routledge.

Felix, U., (2005) E-learning pedagogy in the third millennium: the need for combining social and cognitive constructivist approaches, ReCALL. 17(1):85-100.

Gee, J. P. (2003) What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gee, J.P. (2005) Good Video Games and Good Learning, Phi Kappa Phi Forum 85(2): 33- 37. Retrieved from: http://www.jamespaulgee .com/sites/default/files/pub /GoodVideoGamesLearning.pdf.

Kapp, K.M., (2012) The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Langé G., Cinganotto L., (2014) E-CLIL per una didattica innovativa, Quaderni della Ricerca, 18, Loescher.

Mawer, K., Stanley G., (2011) Digital play. Computer games and language aims, Delta Publishing.

Trybus, J., (2015) Game-Based Learning: What it is, Why it Works, and Where it’s Going, New Media Institute. Retrieved from: http://www.newmedia.org/game-based-learning--what-it-is-why-it-works-and-where-its-going.html.

Vickers, H., (2007) Living (and learning) in an immaterial world, English Teaching Professional. (53):8-10.

Whitton, N., & Hollins, P., (2008) Collaborative virtual gaming worlds in higher education, ALT-J. 16(3):221-229.

Please check the CLIL for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical Uses of Technology in the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|