Introductory Survey and Study of Children and Juvenile Francophone Works

Josilene Pinheiro-Mariz and Jéssica Rodrigues Florêncio, Brazil.

Josilene Pinheiro-Mariz works at Federal University of Campina Grande, Brazil, where she has been teaching French language and literature since 2006. Her research interests are in the relationship between language and literature, literary reading as part of intercultural exchanges and francophone literature. E-mail: jsmariz22@hotmail.com.

Jessica Rodrigues Florêncio is a graduate student in French and Portuguese. Her research interests are in the strategies for teaching the French as a Foreign Language for children. E-mail: jejeflorenciotj@gmail.com.

Menu

Introduction

Literature and the teaching of FFL for children

From the children's literature

About the so-called “francophone” literature

Survey of children and juvenile literary works: some data

Final remarks

Bibliographical references

It is known that to teach a foreign language without favoring a particular country - and/culture - needs some material that can aid in the methodology and the execution of the teaching activity. Thus, it is common to ask what procedures we use for teaching / learning a foreign language in order to "expand the horizons", not favoring only a certain place/culture. This concern is further aggravated when it comes to teaching French to children in an exolingue context. This is because we are aware of the great importance/care that early childhood education needs, since it is known that we are dealing with the formation of a human being and so we should regard this teaching as something serious, because it is part of an education for life (UN, 2015).

Based on the importance and concern of early childhood education in the education of children, we think of methods that can help in designing entertaining activities, considering that, creating a playful environment in the teaching process is required in order to make the child’s first contact with the language pleasant (Vanthier, 2009). In affirming this, we immediately think of literature as a means that can help in promoting such education. Literature in this case constitutes a connection, necessary for the development of language, considering that literature and language are inseparable elements (Fiorin, 2012). This is not to say that literature should be "used" only as a pretext for teaching the French language or for any other didactic purpose. On the contrary, the childhood literary reading, especially in early childhood, appears as an element that brings great benefits not only with regard to language, but also in other respects (Poslaniec, 2002; Reyes, 2010; Vanthier, 2009 ), on which we gradually discuss in this investigation.

As a result of these considerations, we realize the importance that literature has in teaching French as a foreign language for children (hereinafter FLE), since it allows to open a range of possibilities for developing such teaching. From this, and based on previous researches, we can state that recognizing the importance that literature has in teaching a foreign language is, in fact, the first and most formidable step, but it is not unique. In the course of research conducted earlier, this same perspective promotes French as a Foreign Language (henceforth FFL) education for children, having literature and literary reading as support. For example, we realized that there is a lack of (re) cognition of books ever written for children in French and by Francophone writers worldwide. We note that most books that are recognized in this context are part of the large collection of books and writers that exist in France and/or Europe. So, we think of other books that were not only produced by French writers, but authors in other areas of the planet, such as the French-speaking world; that is, countries where French is spoken outside Europe.

Thus, we think of the possibility of exposing the existing works in the French-speaking world, making them stand out in order to render them visible and make many readers perceive the size of the Francophone literary world. Thus, this research not only showed the benefits that literature can bring to the FFL education for children, but also conducted a survey of book publications throughout the French-speaking world (except for the literature of the Hexagon country: France). Thus, the theoretical framework of Gaonac'h (2006), Fiorin (2012), Vanthier (2009), Poslaniec (2002), Reyes (2010) and others were critical to support our reflections. The books survey had as a data source and base, some websites as Association Internationale des Libraires Francophones (the French international libraries association), Takam Tikou, BnF, La revue des free pour enfants, Communication-jeunesse among others.

Our research is divided into two great moments; in the first, we discussed about the literature in teaching FFL for children as well as carrying out a survey on Francophone children's books. In the second step of our results, we did the regional division of the works of this French-speaking world; highlighting the most outstanding genres per region, as well as those which stood out in the whole books survey. By this, we discuss the results, trying to point out a few copies of each region of the French-speaking world, in order to determine the elements that promote foreign language literary enjoyment as well as better intercultural connections.

In this study, we understand the Francophone literature as a unique support for teaching/learning of a foreign language, in our case FFL for children. From our work proposal, it is common to hear the following questions: why teaching FFL for children? If there are advantages in teaching a foreign language at this age, what are they? It is from these questions that we take a greater allocation and construction of our research. Why in childhood? According to Reyes (2010), for instance, "Early childhood is defined as a ‘vital cycle’ period in the lives of human beings. It starts from the intrauterine stage to six the years of age" (Reyes, 2010, p.18). This implies that children at this stage are more susceptible to various learning, one of which is learning a new language, since they are more likely to maturation and learning due to the limitless of childhood plasticity, that makes children more " skilled "to learning. This is because it is in childhood that the neuronal growth happens in an intense pace (Reyes, 2010).

Thus, we can say that this period is the most favorable one for the acquisition of a foreign language, since the child's brain is still under development and may make the acquisition of new language easier (Gaonac'h , 2006). That is, during early childhood, the child is able to acquire a proper understanding and pronunciation in a foreign language (Cuq & Gruca, 2009).

The importance of adult intervention in children's development process emerges from these initial reflections. According to Reyes (2010), as far as literature and language teaching are concerned, there is a creation of a triangle between the adult, the child and the book, which can be constituted with the figure of the father, or the mother or of the teacher, the book and the child, taking them to new findings regarding the symbolic literary world. In other words, it is from the literature, storytelling, that the child will realize a new world, the literary symbolic world in which she/he can make new discoveries. With respect to this statement, Poslaniec (2002) rightly argues on the possible interaction between the "reader", in our case "listener" and the story told. For him, there is not only one interpretation, but various interpretations of what is read (or heard, in the case of storytelling). The child will then have the power to use their background knowledge to merge with the story of the book and then get the various possible interpretations.

Also according to Reyes (2010, p. 49), "as this happens, the articulation system of the child gets mature." This allows us to say that in the reading process, the creation of this triangle between the book, the adult and the child, enables the child to make discoveries of the symbolic world and as this happens, it matures its articulation system in the mother tongue. We can say that these findings and this maturity can happen not only in the mother tongue, but also in the foreign language. Thus, we believe that literature will confirm the development of teaching/learning of the French language.

In addition, this Colombian scholar states that "the power to disrupt, recover, recreate, explore and play with words ends up being crucial in the production process that the children are living" (REYES, op. cit., p. 51). It is then that we realize the importance of the role of literature in the child's human construction. Using her own words, "the new paths that open the child's imagination, can also be explored in the books that are read to him/her" (Reyes, 2010, p.51).

As the child grows and turns his verbal experience into a usual form of communication, she/he then encounters a gap between the nonverbal experience and the former. That is, as we take possession of the gift of expressing ourselves, we also find that such a gift is imperfect. Thenceforth, we again identified literature as an element that lies precisely in these areas. Literature has this "power to leave traces in our words and also to travel to imaginary worlds" (Reyes, 2010, p.56). And it is in this range of "possible worlds" that the child will come across when she/he starts passing from being "speechless" to become a being "speaking ability". The child thus has before him/her a variety of possible worlds, mental language models that she/he keeps in order to perform actions in a world full of social and cultural challenges. Proof of this is what Batt (1987) says of game and reading, namely "comme le jeu, la lecture d'appréhender permet le réel sur le monde de l'imaginaire". In our free translation, "Just as a game, literature helps to grasp the real from the imaginary way of thinking" (quoted Poslaniec 2002, p. 134). So the child can emotionally identify himself/herself with the character without losing his/her own identity.

We once again reaffirm the importance of working with children as far as teaching/ learning a foreign language is concerned, taking into account that it is at this stage, early childhood, that the child is more conducive to a rapid learning of new words, ranging from "eight or ten words" learned daily (Reyes, 2010). Also, when learning a foreign language, the child faces the other person as a subject of language, from different places and consequently of different cultures (Vygotsky, 1995 cited in Pinheiro-Mariz; Silva, 2012), since the learning of a foreign language is not only limited to the acquisition of language, but also involves contact with the other person. So a 'diving' into another culture takes place, making him/her to reflect on his/her own culture. Thus, the class of FFL is the right time to meet and try to understand the various forms of human experience.

It is also at this stage that the child will incorporate, even unconsciously, certain grammatical rules, by exploring another world, the imaginary world. There is thus a 'middle ground' between the real and the symbolic and it is what we call the art of literature. Literature then becomes a "[...] source of nutrition that the child uses in search of mental and symbolic tools to organize the flow of events, lie, prove and decipher himself in a temporal chain that establishes the language.” (Reyes, 2010, p. 63).

This literature that serves as a nutrition link for children is not only written but also oral. As the story is told, when orally, it helps children to think in the language, thus building a chain of meanings in order to perform the narrative reading being told. To that end, Vanthier (2009) states that the stories made for children are to help them grow. For her, a child that listens to a story and sees the illustrations in the book sees language and pictures as sources of pleasure, "plaisir de la découverte des situations, plaisir de la recontre des personnages, Plasir du langage", or in our translation “…pleasure of discovering situations, pleasure of meeting characters, pleasure of language…” (Vanthier , 2009, p. 61). Also, while listening to stories and seeing illustrations related to these stories, the child begins to store images, building a linguistic and cultural memory. The images alongside with the story establish an important role in the process of teaching/learning of the FFL for children (Poslaniec, 2002). Vanthier (2009, p. 61) emphasizes this importance of literature in FFL education for children, pointing out that «La littérature de jeunesse constitue un terrain où l’enfant recontre l’autre, autour du livre, à travers le partage de références fictionnelles qui s’entrecroisent, tissant ainsi un réseau intertextuel d’une langue à l’autre et d’une culture à l’autre» [Children's literature is a field where the child through a book descovers the other, by sharing fictional references that cross each other, thus weaving an inter-textual network from one language to another and from one culture to another. Our traslation].

Poslaniec (2002) also evokes the encounter with the author of the book, affirming that literature is nothing more than the product of the author's life. Thus, we can say that the child will come into contact with the author's life, through the book, that is, with new worlds, new cultures. Thus, according to Poslaniec, “le texte littéraire révèle une construction rhétorique – ce qui est vrai, mais partiel », sentence can be understood as “The literary text reveals a rhetorical construction - which is true but partial” (2002, p. 123).

It is from these first reflections on literature and teaching/learning in early childhood that we can already say the importance of literature in cognitive and cultural education of children, as we have seen several features that privilege it within the scope of teaching/learning of FLF and especially for children.

With regard to literature for the youth, despite the importance it currently has in FFL teaching for children, Chelebourg and Marcoin (2007) discuss the difficulty that this type of literature faces, as it was long regarded as inferior or marginal. This also happens with the so-called francophone literature, since it was also long regarded as a marginal literature. Proof of this is the continued struggle for these francophone texts to have their place in the most diverse areas, such as documents like dictionaries, anthologies and even in textbooks (Allouache, 2013).

Apart from the lack of recognition of these literatures, Poslaniec (2002) and Allouache, (2013) believe that literature for youth was also seen as not non-literary and for this reason, it was for centuries called sous-littérature. Thus, la littérature de jeunesse (in Brazil, the term; juvenile literature was adopted) is a new term. In Brazil, the term; juvenile literature was adopted. However, the writings directed to children are old, because the small ones were always in contact with an oral literature, such as, short stories, fables, songs etc.

Consequently, we can highlight various genres that this literature embraces and that Chelebourg and Marcoin (2007) called traditional, such as songs, comptines, poems, short stories, novels, newspapers. There is therefore a range of genres that children's literature involves, directing us in our choice of a literary works survey. It is important to mention that we try to cover all these genres already mentioned, intending thereby to sort them by continents and/or by countries. Thus, after this step, and based on the survey, we may affirm the genres that stand out in the French-speaking world and in which regions they come from. If we stop to consider, one must emphasize the importance of this research that starts with this survey, considering that we have a range of paths, which can be traversed/explored. This highlights the importance of the details involved in our bibliographical research which is also quantitative/qualitative.

Getting back to our reflections on literature for youth, we know that, according to Chelebourg and Marcoin (2007), it obviously has its functions geared for youth. However, these functions run through the course of three groups: the edification, the education and the recreation. Regarding the edification, we have literature in which there is advice directed toward religion, morality and ideology. With regard to education, literature uses education to pass information; the narrated information, laws present in the narration, the narrative information and the education itself. As for recreation, we have the “‘bêtises’ dessinées, ‘bêtises’ racontées, les livres-jeux, les médiarts” [comics, film, television, internet sites etc.] (Chelebourg & Marcoin, 2007, p. 81-. 88). However, we do not say that cinema, comics and other events that are part of the recreation group, sorted by Chelebourg and Marcoin do not edify. We know that these genres may have the same value as others, when properly used, and can also provide cognitive and cultural development of the child. We will gradually see this in the development of this research. Reflecting this classification of children's literature conducted by scholars, we can say that literature for youth can play various roles in the teaching/learning of FFL, not only on the linguistic side, but also in the development of ethics (this covers several aspects, including cultural aspects), education and recreation.

With respect to the themes, Marcoin and Chenebourg (2007) cite three major groups: childhood writing, the actual writing and the taste of adventure. In the childhood writing, we have the heroic transposition, affective links/elements such as parents and animals, bildungsromans [novels in which the main character grows throughout the story], term that means novels in which the main character grows throughout the story. We can find different types of writings in this type of narration, such as family affairs and daily life. It is a true Romanesque reconstruction of childhood, where there are stories about school, colleagues, and friends. The real is also reconstructed to give time to the heroes, the princes and princesses etc. In the process of writing, we have social issues, manners and life lessons, true stories and the discovery of the world. This can be a way to report possible irregularities existing in the social world, political etc. In addition, the child, while reading a book or listening to the same story, he/she can discover the world by means of the stories told to him/her and through the true or fictional stories also shared with her. Finally, the last group "adventure like". We appeal to the gods, weather avoidance, puzzle, mystery and adventures and fantasies. As I said, this group includes characters’ adventures and mysteries surrounding the story.

So after considering some aspects that are involved in children's literature, we want to emphasize on the variety of topics that this literature approaches. Although it was long considered as a marginal literature, it already has a major force in such a short time of existence. Although it still goes through impeachment by perhaps being recognized as non-literature or something outside literature, we dare say that the literature for young readers has its peculiar characteristics, the same way as other types of literature do have. And these are strong characteristics that mark the power it has to involve a child, young and/or adult readers. However, it is not our objective to discuss about what literature is or is not; our main goal, as previously pointed out here, is to conduct a survey of children and juvenile Francophone literary works. Thus, based on the ongoing reflections, we want to add to these considerations the studies concerning the francophone literature and their roles in teaching FFL.

Taking into account the large number of French-speaking countries, it is important for our data collection to ask ourselves the following questions: What is francophonie? What works are considered francophone? It is from these questions that we note the need to expound a little on this subject: the Francophonie. Also, it is important to say that theme of Francophone is a notion, far from being a shared view by members of this French-speaking community. This is because it is a notion that can be treated in various fields of the human knowledge, such as geography, sociology, history, economics, politics and, of course, literature. So, this being our focus, we will discuss this domain according to some scholars in the Francophone Literature.

According to Brahimi (2001), for example, a few years ago there was an average of sixty million people speaking the French language worldwide; however, the International Francophone Organization points to about two hundred million speakers of the language of Molière. Today it is the fifth most used language in the world. But the fact that the French language is present in many parts of the world, notably in all of Earth's continents, does not mean all those who speak French do have the same culture. The French language undergoes changes, though minimal as far as pronunciation and writing are concerned. Thus, francophonie has a dual history due to its long and extensive historical wide range. So, it is said that French literature is developed in order to provoke the awakening of mixed feelings to those who read and produce it. In this sense, there have been numerous attempts to define this literature, considering the fact that many distinguish between French literature and Francophone literature, creating a center and a periphery (Allouache, 2012). Attempts to set the Francophone literature were not successful, since the existing definitions do not make clear whether the French-speaking literature also corresponds to French literature.

Moreover, the Francophone literature is still "marginalized", given that, according to Allouache (2013), it is rare to find this Francophone literature in textbooks for the teaching of FFL and even for French as a mother tongue. Still regarding the exclusion of these works, it is also important to mention the approach and the rating that this literature has in anthologies and literary dictionaries, they are most of the time recognized as "non-existent" or as part of French literature. This happens because of geographical and geopolitical factors that suggest a break between these two literatures. (Allouache, 2013). So, reflecting a little on this dark aspect of Francophone literature, it is important to note that the accomplishment of our survey did not excluding the France literatures, because we do not claim that French literature and Francophone literature are not in the same category, but we want to give emphasis on Francophone literature, outside of France, which has long been forgotten and marginalized. Of course, just as there exists the African Francophone literature, there is also the French Francophone literature. Despite the possible redundancy impression on our last phrase, what we mean is that in the vast French-speaking world, there is no literature with the same characteristics in a way that makes them similar in all respects. As I said earlier, since the French language changes, its speakers are many, therefore the literatures from these places have different characteristics.

Thus, based on what we have seen, we can clearly perceive the focus of our research. The children's literature that was for a long time and even today considered as a non-literature" or something outside literature, is often classified by francophone literature, as a literature out of French literature. Think of the difficulties that children's francophone literature faced and faces, urges us to further deepen our research because it increases our desire to expose and give recognition to this literature.

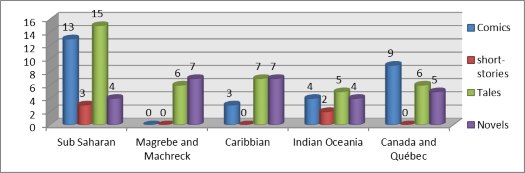

After conducting the book survey, for a total of 100 books, we note that there was easy access to books in some parts of the French-speaking world. However, we identified for example some difficulties in accessing the Francophone literature for children in Oceania Indian, and this reflected in the number of books cataloged found in this region. This does not mean that literature from this region is small, but that accessibility to these literary works is limited, perhaps due to the inaccessibility of the local language or even culture almost not known worldwide. Also, we realized that some genres were more frequent in some regions than in others. Therefore, we believe that it is important to draw up the following chart in order to illustrate the kind of literature that was found in each region of the French-speaking world.

Graph 1: division of literary genres per region (percentage).

When observing the chart above, we perceive that the diversity of genres that were listed in this survey is highlighted: comics, nouvelles, stories and novels. Unfortunately it was not possible to include other genres, considering that our focus is toward a more general overview of this literary production throughout the Francophone world. However, this limitation does not undervalue the results of our research. Thus, we see that in every region there is a genre that stands out more than others: in sub-Saharan Africa, tale; in the Maghreb and Machreck, romance; Caribbean, tale and romance; Indian in Oceania, tale; in Quebec, comics [Some scholars do not see comics as a literary genre. As stated earlier, the literature for young people has long been regarded as an inferior literature, or something different from literature. This is even stronger when it comes to comics. In this research, we consider comics as a literary genre that is in a full and strengthening ongoing consolidation]. In the comics, it is important to highlight that some scholars do not see it as a literary genre. As stated earlier, the literature for young people has long been regarded as an inferior literature, or something different from literature. This is even stronger when it comes to comics. In this research, we consider comics as a literary genre that is in a full and strengthening ongoing consolidation. So, from these data, we intend to analyze a book per region, emphasizing on the gender. In our analysis, we ascertain whether the genres classified in those books favor the training of children and adolescents readers and provide them with better intercultural bridges.

The first genre that we analyzed was a tale from a book from sub-Saharan Africa – and is the most popular in this region. The book was written by an Ivorian author Véronique Tadjo and is titled Ayanda, la petite fille qui ne pas voulait grandir. The work was published in 2007 and tells the story of a happy girl who always smiled, until the day when a terrible war broke out. A senseless war. Her father, who was so sweet and so kind, was forced to fight in this war. As a result, he never returned. Realizing this, after the war ended, the heart of Ayanda was broken and her sadness turned into anger. She then decided to stop growing. But had no choice but to grow, because she needed to take care of the house, her grandmother and her brother. Until one day the village where she lived was invaded by thieves. So, to try to help, she decided to grow up to the size of a baobab. In so doing, she saved her village and was recognized for her effort.

The story in Tadjo’ book can be analyzed in various ways in FFL teaching framework for youth and children. It demonstrates the reality of many families who lost relatives in civil wars that still occur in Ivory Coast. It is also the reality of girls/ who must take care of their homes and seek recognition. Thus, the story brings the reality of the characters to the young reader, causing him/her to get to know the culture of the people that are undoubtedly present in this book.

As for the Maghreb and Machreck regions, we found the literary genre called novel as the most recurrent genre in our research. Even if the most commonly found genre in these regions of the French-speaking world has been the novel due to accessibility, we analyze some stories that are available in http://www.conte-moi.net site and are easily accessible. In this site for example, stories like Peau de vachette (anonymous), Le teigneux (Aicha Ait Berri), Les deux loups affamés (Ahmed Hafdi), Un chat Vertueux (Aicha Ait Berri) are available. These tales, and other gifts found on this site, narrate stories belonging to the culture of the regions of the Maghreb and/or Machreck, including the stories, customs and traditions of these people. In addition, at the end of each story, there is a moral lesson, thus allowing not only the linguistic aspect, but also exposing the cultural and educational nature in this book.

The third book originates from Caribbean and is part of the romance genre. It was written by the most famous writer in Guadalupe called, Maryse Condé, and is entitled Rêves amers. Published in 2001, it tells the story of a thirteen years old girl named Rose-Aimée who lived very happy in his little village in Haiti, until the day that poverty forced her to leave her home. Placed in the city as a maid, she supports the contempt of her boss. Fortunately, she wins Lisa’ friendship. So, this novel allows the young reader to be aware of the fact that the various difficulties the Haitian people face began during colonization. Still, the young reader will come to know about illegal immigration, slave trade, child labor, as well as children's rights.

For the Indian Oceania regions, we saw that the literary genre that stood out in our research was the tale. Thinking again on accessibility, through our research on the Internet, we found http://www.iletaitunehistoire.com/ - a website that has tales, stories, fables, comptines. Thus we found the following tales; Le tigre, le brahmine et le coyote. This tale tells the story of a rich Brahmin releasing a tiger from its cage. The tiger promises not to attack him, but as soon as the cage is opened, the animal pounces on the Brahmin to eat him. The Brahmin then interrogates five animals to see if it is right to allow the tiger eat him. Another version of this story is also found in the book by Sara Cone Bryant titled Le tigre et le petit jackal, as well as on the site http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xoc6ku_les-histoires-du-pere-castor-le-petit -chacal-tres-malin_fun, in video form. Then this story can be found in different formats. As earlier said, this story is about a Brahmin. The Brahmins are important characters in Hindu society. So this tale is easily accessible and also has a great cultural heritage that could carry the child into a new culture, new religion, new people, and getting to know them well. Thus, no doubt, this and other tales also present at il était une histoire site promote cultural exchanges in order to make the child see his own culture from another angle, from another culture (and vice versa). In addition, it should be clear that there is wide range of tools (such as video mentioned) that can be used in the story-telling process.

The fifth and final book we analyzed is from the Quebec region and belongs to the genre comics. Its writer is from Québec and is called Elise Gravel and the book is entitled le professeur du leçons Zouf - leçon 3: l'amour. It was published in 2013 and tells the story of a teacher who is graduated from the course of "tudologia" [Science of knowing everything ], that means a Science of knowing everything and therefore knows everything. He gives valuable lessons for everyone. In this book, the lesson that professor Zouf will tell will be about love. Thus, it will serve as a guide for his assistance to get the love of a girl. But for that, Professor Zouf gives a lot of advice that his assistant has to follow. With this history, we can already see the educational value that this book has, because it makes the child think about the advice given by the teacher and can apply in his/her life. This book is part of a series of books that bring valuable lessons through the already known professor Zouf and his stories.

With regard to this survey, it is clear that the most featured genre for this kind of literature is the story, followed by comic books and later the novel. This probably happens because the tale is too attached to oral traditions and the history of the people that produced it, thus calling the attention of children and young people. Another reason is the accessibility and the short length of most stories. Of course, these features may be stronger in comic books, given that apart from some verbal text, it is common to use images that combine with the written text. However, comics are still earning its place in the literary world and especially in the French-speaking world from Canada.

After the above reflections, we can highlight the following results. With regard to children, we can say that childhood is a stage of life during which the child is more prone to learn a foreign language with ease, since they do not have the barriers that settle in humans in adulthood. There are countless reasons why we can say that childhood is the most propitious stage for learning a foreign language. With regard to that evidence, Reyes (2010) asserts that "early childhood is a vital cycle period in the lives of human beings that stretches from the intrauterine stage to six years of age" (Reyes, op. Cit., p.18). This is because the child’s maturation and learning possibilities are higher, due to his unlimited plasticity that favors learning at this age (Cuq & Gruca, 2009).

Apart from the above, we can ensure that literature is an important element in the development of teaching/learning of French. Why do we say this? This is because the child relies a lot on the imaginary world and in a fascinating universe. In this sense, according to Poslaniec (2002), the literary reading favors this game between the real and imaginary worlds, causing the child to learn what is real from the imaginary world. From this angle, it can be said that the child will incorporate certain grammatical rules, even if unconsciously, in his/her imaginary world. Finally, it allows the child to discover a symbolic world and hence the maturity of his/her articulation system in the foreign language she/he is learning.

Presently, we realize the importance of literature in teaching/learning FLF, not only in language development but also in the cultural, social, moral development etc. As noted earlier, recognizing literature as one of the most effective element in education is undoubtedly a big step, but it is not the only one. It was from these findings that we carried out an inventory of francophone literary works for children and we found a huge variety of existing publications in French to this specific public. This is contrary to the difficulties faced by Francophone literature for children today because, despite the barriers, this literature is immensely flourishing today. What we mean is that the amount of literary production surprised emphasizing on the need to study the Francophone literary work. This also allows us to conclude that the horizons are not so clear, in other words, they are not directed to one place or one country. Thus, from our findings in the context of this research, we seek to broaden the horizons beyond a privileged space at the expense of others.

We also hope that the survey can be an important collaboration for other areas to see the Francophone literature in a different way, not as a less rich literature, but as plural in various aspects such as its large quantity, diversity of genres, themes and the existing cultural density in each book. Based on our experience and survey, we realize that the local culture (of each region) is impregnated in each book. We do not highlight this as a negative aspect, however, it proves that each book can help a child see the world differently. For example, he may come to look at the African people as being culturally rich. The child may realize by herself/himself that there is no superiority between people and cultures, but that there are differences and peculiarities which do not indicate inferiority.

With these considerations, it is easy to discern the existing dimension of the francophone literature and its multiple aspects. In contrast to this rich aspect, it is almost impossible to believe that many researchers and other scholars do not realize the value of the Francophonie and its literature. It is worth noting that, even though our focus is the survey, the reflection on this topic is what feeds this investigation. We also know that the French literature of France has historically received much more investigative care mainly for historical reasons, but we believe that labeling a particular literature as marginal or inferior is not an acceptable attitude in the XXI century. We then show how much French literature outside France is important and necessary for the teaching/learning of FFL.

Thus, coming to the end of our research, we have succeeded to answer the two main questions that guided this research: Can literary works written in French, and published outside France, favor the formation of apprentices readers of that language? Do the literary genres produced in this context stimulate intercultural bridges, forming young readers who lack prejudices? Regarding the first question, based on our data and theories, we affirm that the Francophone literature for children and youth can be a world of knowledge to its readers. The reason for our emphasis here is because we understand how important it is the role that literature plays in the FFL teaching context for the younger people. As far as the second question of our research is concerned, we affirm that it is not only the most produced genres but all the genres in the French-speaking context which can favor and stimulate intercultural connections, broadening the vision of the young reader, and also making him/her to consider the other just as she/he considers herself/himself.

Allouache, F. (2012). Réflexions à propos des littératures dites “francophones”. Revista Letras Raras, v.1, p. 17-28.

Allouache, F. (2013). Marginalização das literaturas francófonas nas antologias e dicionários literários. Trad.: Jéssica Rodrigues Florêncio e Josilene Pinheiro-Mariz. In : Pinheiro-Mariz, J. (org.). Em Busca do Prazer do Texto Literário em Aula de Línguas. São Paulo: Paco editorial/ Campina Grande: EDUFCG. p. 51-60.

Avelino, N. V. F. (2012). Leitura literária na educação infantil: narrativas como caminho para fruição. 2012. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Unidade Acadêmica de Letras, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Campina Grande, 133 f. (149 f.).

Avelino, N. V. F. & Pinheiro-Mariz, J. (2011). A leitura literária como elemento 'sine qua non' para a formação humana. Revista Saúde e Ciência, v. 2, p. 121-131.

Blondeau, N. & Allouache, F. (2008). Littérature progressive de la francophonie. Paris, CLÉ International.

Chartier, A. M. (2005). Que leitores queremos formar com a literatura infanto-juvenil? In:___ Leituras literárias: discursos transitivos. Cidade Nova: Autêntica. p. 127.

Chevrier, J. (1999). Littératures d’Afrique noire de langue française. Paris: Nathan Université.

Cuq, J.-P. & Gruca, I. (2009). Cours de didactique du français langue étrangère et seconde. Grenoble: Press Universitaires de Grenoble.

Chelebourg, C. & Marcoin, F. (2007). La littérature de Jeunesse. Paris : Amand Colin.

Gaonac'h, D. (2006). L'apprentissage Précoce d’une Langue Étrangère ; Le point de Vue de la Psycholinguistique. Hachette Livre, Paris Cedex.

Matateyou, E. (2011). Comment enseigner la littérature orale africaine. L’Harmattan, Paris.

Moreira, H. & Caleffe, L. G. (2008). Metodologia científica para o professor pesquisador. Rio de Janeiro: Lamparina.

Paes, J. P. (1996). Poesia para crianças. São Paulo: Giordano.

Pinheiro-Mariz, J. & Silva, M. R. S. (2012). Da aprendizagem de uma língua estrangeira na primeira infância: a literatura como um caminho para imersão no imaginário do universo infantil. Revista UNIABEU, v. 5, p. 32-47.

Poslaniec, C. (2002). Vous avez dit “littérature » ? Paris: Hachette Livre.

Reyes, Y. (2010) A Casa Imaginária: Leitura e literatura na primeira infância. São Paulo: Global.

Silva, M. R. S. & Pinheiro-Mariz, J. (2011). Literatura em aula de FLE como um caminho para a imersão da criança no universo do imaginário. Anais do VII SELIMEL - Seminário Nacional sobre Ensino de Língua Materna e Estrangeira e de Literatura. Editora Realize: Campina Grande.

Vanthier, H. (2009). Techniques et Pratiques de Classe; L’enseignement aux Enfants em Classe de Langue. CLE International, Paris.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1995). Pensamiento y lenguaje. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Fausto.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

|