The SDGs and Global Citizenship: Working with Public Servants in Myanmar (Burma)

Thomas Kral and Shannon Smith, Burma

Thomas Kral and Shannon Smith have over twenty years’ experience in language education and teacher training. They have most recently worked as trainers and managers on international capacity building and teacher development projects in Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka. They are interested in the power dynamics of language in international development contexts.

E-mails: tdkral@gmail.com, shannondeesmith@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Context

The SDGs, global citizenship and critical engagement

SDG-themed tasks which aim to move from ‘Approach 1 to Approach 2’

The role of the trainer

Reports from the field

Conclusion

References

The Sustainable Development Goals provide relevant and topical content which enables learners to engage with global development issues and become more critically aware global citizens. Resources based on the SDGs form part of the coursework on a British Council capacity building and language training project with public servants working for the government of Myanmar (Burma). This paper outlines the context in which the goals are used, highlights the different ways in which the SDGs enable learners to engage with global citizenship and provides examples of SDG based activities which go beyond awareness-raising to enable critical engagement.

While the specific context described may be different from that of many readers, the ideas and principles offered are relevant for a wide range of teachers, trainers, students and other language education stakeholders.

Myanmar is in a period of political, economic and social transformation. After decades of military rule, the country is emerging from recent elections as a nascent democracy, led by Aung San Su Kyi’s reformist party, The National League for Democracy. However, the previous military regime retains significant political power and numerous development challenges persist. Poverty is endemic, infrastructure is poor, human rights are abused and environmental destruction is apparent. Myanmar retains its status as one of the world’s Least Developed Countries (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2016).

As a result of recent political reforms and subsequent lifting of international sanctions, many international development agencies have started working in Myanmar, often forming partnerships and launching initiatives with government ministries and departments. However, the engagement between these international actors and the Myanmar government officials has often been undermined by the public servants’ lack of English language skills and their limited exposure to development issues as they are articulated by the international agencies.

To help overcome these challenges the British Council has been contracted to deliver language and communication skills training as part of a capacity building project with public servants at Myanmar’s Ministry of Planning and Finance. The aim of the training is to improve the workplace communication skills of the participants and to enable higher quality engagement with international consultants and advisors who are supporting Myanmar’s development and reform agenda.

Upon taking up our posts in May 2016 we reviewed the resources provided for B1 and B2 level courses and conducted a needs assessment with the training participants. We found a significant gap between the content in the existing course material and the public servants’ professional and cultural context. Using our previous experience incorporating the Millennium Development Goals into a successful training project with public servants in Sri Lanka, we decided that the SDGs would effectively fill the content gap.

Work with the SDGs represents approximately 50 percent of the course content, with the other 50 percent consisting of general language and business skills training. We have created 17 two-and-a-half-hour interactive lessons based on each of the goals and have delivered these in sequential order.

The resources we have produced based on the SDGs have exposed the public servants to a global perspective on development issues. Most of the learners were educated under the former military regime, which offered limited exposure to the outside world. In addition to awareness-raising, the SDGs provide a topical focus to promote critical thinking skills and governance issues which the learners engage with in their day-to-day work.

Using the SDGs in this way is also consistent with UNESCO’s approach to global citizenship education, articulated in SDG 4 (Education) Target 4.7

“ensure that all learners are provided with the knowledge and skills to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development”. (UNESCO, 2016)

While important in itself in a context with ethnic conflict and numerous governance challenges, global citizenship education among Myanmar public servants needs to go beyond awareness-raising.

Andreotti (2008) describes extending global citizenship education to a process of critical engagement with global issues and interpreting them from a local perspective. Participants are thus encouraged to critically reflect on local challenges within a context of greater global awareness and interconnectivity between the global and the local. Importantly, this approach reduces the risk of participants being told what to think and how to act; instead it asks participants to take ownership of global citizenship on their terms in a locally relevant way.

The following chart contrasts two approaches to Global Citizenship Education:

| Approach 1 | Approach 2 |

| Strategies for global citizenship education | Raising awareness of global issues | Promoting engagement with global issues and perspectives and an ethical relationship to difference, addressing complexity and power relations |

| Potential benefits of global citizenship education | Greater awareness of the problems and increased motivation to take action | Independent and critical thinking and more informed, responsible and ethical action |

| Goal of global citizenship education | Empower individuals to act (or become active citizens) according to what has been defined for them as an ideal world. | Empower individuals: to reflect critically on their cultures and contexts, to imagine different futures and to take responsibility for their decisions and actions. |

| What for? | So that everyone achieves development, harmony, tolerance and equality. | So that injustices are addressed, more equal grounds for dialogue are created, and people can have more autonomy to define their own development. |

(Andreotti, 2008)

Derived from an initiative called Open Spaces for Dialogue and Enquiry (OSDE, 2016) the second approach aims to promote independent thinking by providing ‘safe spaces for dialogue and enquiry’ about global issues and perspectives (Andreotti, 2008). This is especially important in Myanmar, as the previous military regime did not provide public servants an opportunity to freely discuss many of the issues contained in the SDGs. Given that the country is still mired in several ethnic conflicts in which sensitivities run high, the OSDE approach enables both awareness-raising of issues on a global scale and, for the trainer, to provide the participants a non-judgmental opportunity to adapt the SDG to the Myanmar context. Approach 2 further invites participants to examine the impact of local power structures on achieving the SDGs.

SDG 4: Quality Education

For example, the UN SDG website gives the following facts and figures about SDG 4:

- Enrolment in primary education in developing countries has reached 91 per cent but 57 million children remain out of school

- More than half of children that have not enrolled in school live in sub-Saharan Africa

- An estimated 50 per cent of out-of-school children of primary school age live in conflict-affected areas

- 103 million youth worldwide lack basic literacy skills, and more than 60 per cent of them are women

(UN, 2016)

The text can easily be transformed into the matching task below. This task requires participants to critically assess the data presented, both numerically and linguistically, so that the sentences are factually and grammatically accurate.

| 1. | Enrolment in primary education in developing countries | a) of out-of-school children of primary school age live in conflict-affected areas |

| 2. | More than half of children that have not enrolled in school | b) has reached 91 per cent but 57 million children remain out of school |

| 3. | An estimated 50 per cent | c) lack basic literacy skills, and more than 60 per cent of them are women |

| 4. | 103 million youth worldwide | d) live in sub-Saharan Africa |

To enable their critical engagement with this goal on a local level, participants can be asked (in groups) to assess successes and challenges of the education system in Myanmar in terms of the following criteria:

- access to primary, secondary, tertiary schools in urban and rural areas

- access to education in areas of armed conflict

- education opportunity based on gender

- quality of teacher education and teaching

- motivation of teachers

- supply and quality of education facilities and resources

Groups can then brainstorm solutions to the challenges articulated by the other groups. This process moves the participant from awareness-raising (Approach 1) to critical engagement (Approach 2) with the SDG.

SDG 10 Reduced Inequalities

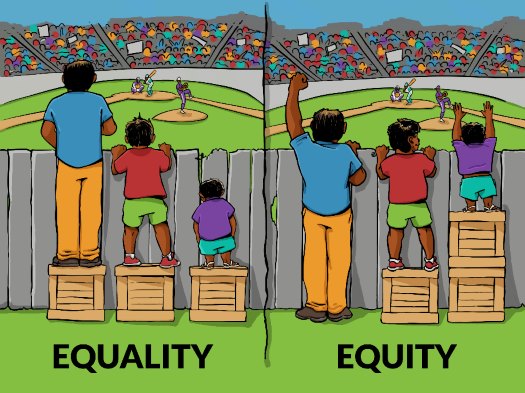

To move from Approach 1 to Approach 2 with this SDG, participants can work in pairs with each partner describing one of the two pictures below. Without looking at the other picture the partners attempt to work out the difference between the concepts of ‘equality’ and ‘equity’.

Interaction Institute, 2016)

In the task below, participants work in groups and have to consider policies and practices carried out elsewhere, but apply their own world views and criteria. Again, this attempts to engage the participants beyond the level of awareness-raising and to consider global ideas on their own terms.

| Policy to address inequality or injustice | Is it fair or unfair: Why? |

| Reserved seats for disabled passengers on a bus | |

| Reduced museum admission and bus fares for senior citizens and children | |

| Hiring a woman manager instead of an equally qualified man to have greater gender balance | |

| Admission to a national monument in a developing country: 25 USD for foreigners, 1 USD for citizens | |

| A new prime minister chooses a cabinet members from different ethnic groups to reflect the diversity of the country | |

The role of the trainer is essential in enabling critical engagement (Approach 2) among participants. SDG themed lessons run the risk of spreading buzzwords and catch phrases among participants who tend to learn and repeat this jargon without gaining an in-depth understanding of underlying meanings. It is especially important for participants to formulate their own definitions of abstract concepts contained within the goals, such as ‘poverty’, ‘human rights’, ‘social justice’, ‘peace’ and ‘sustainable development’. When learners brainstorm problems and solutions around SDG issues, the trainer needs to monitor and invite students to explain, justify and expand on their ideas. The tendency to rely on vague jargon needs to be mitigated by an engaged trainer who elicits a deeper understanding of ideas and requests specific examples. Participants need to be encouraged to consider power structures and other barriers as they come up with realistic solutions to social and economic problems. Without active trainer engagement, using the SDGs in this context risks falling short of reaching critical engagement with global citizenship, with participants offering idealized but unrealistic solutions, articulated for the purpose of satisfying the task in the training room but having little currency in the real world. A key role for the trainer, therefore, is to bridge the gap between ideas formulated in the training room and those acted on in the outside world.

To track the impact of the SDG themed lessons, two rounds of monitoring and evaluation exercises were carried out with course participants. The first was done after approximately 25 hours of SDG related input in which SDG 1 to 9 were covered. Course participants wrote the following comments:

- ‘We can take facts among the SDGs to develop Myanmar.’

- ‘I like speaking about our country’s condition compared to SDGs.’

- ‘SDGs are useful for my work, much more relevant than the textbook.’

- ‘My work is using the SDGs on health and education.’

- ‘SDGs promote vocabulary learning and international knowledge.’

These mostly reflected awareness-raising rather than critical engagement with the issues around the goals.

The second round of monitoring was conducted after 50 hours input, in which nearly all the SDGs had been addressed. In this exercise participants interviewed a partner and wrote a summary of their findings. The following statements were submitted:

- “Before attending the class she threw waste anywhere. Now she does not. Now she sees something and her thinking is related with the study (of SDGs) in the course”

- “She prefers learning about SDGs. The most significant impact of learning SDGs is that her logical thinking is further improved.”

- “Regarding SDGs, she is getting to understand theory and practice for economic development. This supports her work in real life.”

This second set of comments suggest that longer-term exposure to the SDGs resulted in greater opportunity for critical engagement, thus moving from Approach 1 to Approach 2.

As suggested by the participants’ feedback, the SDG themed lessons have gone well beyond awareness-raising on global development. They have additionally resulted in a greater degree of critical thinking and changes in personal behavior. Hopefully the lessons also encouraged the participants to take ownership of the SDGs and to become global citizens on their own terms. At that level of critical engagement, the public servants will be better positioned to support Myanmar’s many challenges in achieving sustainable development.

Andreotti, V. (2008). Innovative methodologies in global citizenship education: the OSDE initiative. In: T. Gimenez and S. Sheehan, ed., Global citizenship in the English language classroom, 1st ed. [online] London: British Council, pp.40-47. Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/global-citizenship-english-language-classroom

Interaction Institute, (2016). Illustrating Equality VS Equity. [online] Interaction Institute for Social Change. Available at: http://interactioninstitute.org/illustrating-equality-vs-equity/

OSDE, (2016). [online] Available at: http://www.osdemethodology.org.uk/

UN, (2016). Education - United Nations Sustainable Development. [online] United Nations Sustainable Development. Available at: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/education/

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, (2016). [online] Available at:

http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/cdp/ldc/ldc_list.pdf

UNESCO. (2016). Global Citizenship Education. [online] Available at:

http://en.unesco.org/gced

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|