Personalising Language

Silvia Stephan, Bodensee, Germany

Part 1 : Effective and affective approaches to textwork

Many coursebook texts or newspaper articles include vocabulary, collocations, phrases, statements and structures that are worth exploiting to stimulate conversation even before reading the text, particularly from a pre-intermediate to an advanced level. No matter whether we perceive language through our eyes or ears, whether we read or listen to a text, the same techniques or approaches can be used and even adapted to different language levels. I usually have students keep their books closed while sensitising them to the topic to come or while introducing some new language. By introducing and preparing students I mean, for example, confronting them with extracts from the text, giving them the opportunity to do something with the bits and pieces, to experience and even play with language in their own way, including the practice of the four skills. The following activities exemplify different effective and affective approaches to textwork.

1 Vocabulary-oriented text preparation

- Depending on the level and length of a text, select and dictate 15 - 20 words from the text you intend to read with your students later.

- Ask students to list the words and to tick those that relate to their personal life or situation in one way or other. They can tick while writing or add the ticks to the whole list later. Explain the meaning of unknown words only when asked to do so.

- In small groups, students compare their lists giving reasons for their choice.

- Depending on the kind of text, students can also grade their ticked words according to personal importance. Or they might choose five words of their list which are most relevant to them. No matter what kind of task you set, it is important to give students a good reason for writing the words and to use them meaningfully and personally without necessarily pointing out that the task is also meant to be a vocabulary or text preparation.

The following words serve as an example and are taken from a text called 'Holidays are Hell'. I would start off by asking students to draw an item related to one of their holidays which they then talk about or to share their experience about a particularly exciting holiday they once had. This fluency practice can be done in pairs followed by the vocabulary dictation mentioned above:

luxurious, unpleasant, vast expense, nervous wreck, strange food, magical, calculated, amuse myself, invigorating, misunderstandings, ridiculous, tensions, tip everyone, horrid, family togetherness, holiday ritual, jealousies, unwind, bad temper, enjoyment

2 Topic-oriented text preparation: expressing one's own opinion

Discussing given statements might seem old-fashioned, but maybe not if done before reading the text and in different ways. The technique can be applied to lower as much as to higher levels. I even use it when dealing with newspaper articles in advanced conversation classes who always enjoy writing as a variation to speaking only. As in the vocabulary-oriented text preparation, students are given the chance to express their opinion, feelings and ideas using parts of a still unknown text which serves as a stimuli as much as a linguistic preparation.

- Ask students to keep their books closed.

- Dictate the statements you have prepared and extracted from the text you are going to read in class later.

- Students could order the statements under three headings: I agree, I partly agree, I disagree (completely), or just tick the ones they agree with. Writing is good practice and gives time for thought, apart from the fact that hand-written language looks and makes it more personal to 'work' with.

- In pairs or small groups, students express and compare their opinion referring to the individual statements. If time permits, they finally report back to the class.

- In groups or in class, students speculate on the attitude, opinion or the kind of experience the author of the article might have had. A 'secretary' can take notes if done in groups to report to the class later.

- When speculating, support students with the functional language necessary to express assumptions. Collect and write them on the OHP/board as a visual help, eg.: The author might (have) ... / He/she probably ... / It seems as if ... etc.

- As an alternative and for classes of about 10 to 20 students, type and cut the statements into individual slips. Number each statement.

- Ask students to work in pairs or groups of three, depending on the size of class and the number of statements. First, hand out one statement to each pair/group.

- Students discuss their statement without necessarily taking notes.

- When ready, ask students to move their slip to the neighbouring pair/group and to exchange their opinion on the new statement.

- Limit the talking time on each statement and ask students to pass their slips on until they've discussed all of them.

- Try to take notes of the mistakes worth correcting at the end.

The following statements represent an example and are taken from the text 'Holidays are Hell' again. I don't think it is necessary to print the full text here to understand the procedure and the effect of the activity:

1 I find every aspect of the holiday ritual unpleasant.

2 Unless you are a millionaire, it is impossible to be as comfortable on holiday as at home.

3 Instead of family togetherness, there are tensions, jealousies, misunderstandings and outbursts of bad temper.

4 On holiday, I must eat strange food at vast expense at times determined by someone else.

5 We go on holiday to unwind and return as nervous wrecks.

6 We have become persuaded that this horrid and costly experience is central to our happiness.

3 Topic-oriented text preparation: expressing someone else's opinion

This time, students don't represent their own opinion as shown in the activity above, but the one of a person they know well. The statements below only give you an idea of the kind of text and topic suitable for projecting an opinion on to someone who is not present.

- Ask students to keep their books closed.

- Ask them to think of someone (in the following example it needs to be an elderly person) they know well, admire and/or like very much.

- In pairs, students name the person they have in mind and briefly talk about him/her.

- Dictate the statements you have prepared and extracted from the text you are going to read with the class later.

- Students write the statements down, keeping the person chosen in mind and adding a tick to every sentence they believe the person might agree with.

- With a new partner or in small groups, students compare their results giving reasons.

- If they like, students can share their impressions in class.

The following statements are extracted from a text called 'A gap in a life' and should exemplify the instructions above. It deals with the possibility offered to young people who are interested in taking a year off by either doing some social work or by travelling around the world. The narrator of the text is a 67-year-old man. That's why students should think of an elderly person they know well.

1 I regret not having had a year off.

2 I might have headed for the Antarctic.

3 I would have felt tempted to spend some time in the jungle.

4 I wouldn't have enjoyed going to out-of-the-way places that are off the normal beaten track.

5 I would have stayed away from the tourists.

6 I would have met the locals and sampled their way of life.

7 I wish I could have gone abroad and experienced another culture.

8 I would have appreciated the quiet pace of life.

9 I might have gone in a Land Rover, moving around Europe.

10 I still feel alert enough to take advantage of all the possibilities offered.

There's no denying that I not only chose this text and the statements to prepare students for the reading part, but to give them the chance to practise the third Conditional in a contextualised and therefore meaningful situation (If he had had/had been given the chance to take a year off he would/could/might have..).

(texts and ideas are taken from 'English Network Conversation' by Silvia Stephan, Langenscheidt)

PERSONALISING LANGUAGE

Part two: Effective and affective approaches to lyrics or songs

1 Topic-oriented listening preparation

I usually use song-texts as a basis for conversation, starting at a lower-intermediate level. This does not exclude the final singing in class necessarily. Even pop-songs often have a meaningful contents and lend themselves for discussions and the practice of the four skills. Before playing the song or presenting the text, it is essential to involve students in speculating tasks thus arousing interest or trying to give language a personal meaning, sometimes even playfully.

- Choose some lines from the lyrics and list them randomly in mixed order and in two possible matching blocks, A and B. Either dictate, photocopy or write them on the OHP/board.

- Ask students to work in pairs and to try to match each line of part A with a line of part B, putting them in any order they like without adding any new words.

- Tell students to write a complete verse using all the matching parts and to finally give their 'poem' a title.

Here's an example of some extracts taken from the song 'I Can See Clearly Now' (sung by Johnny Nash to raggae beat 1966). This idea can be adapted to other songs, of course, but not every text lends itself to be used in the same way. The author of the song talks about personal feelings and situations of life relating them to the weather. A topic which is inviting to talk about, particularly before listening to the song.

As a warmer, I first dictate the following weather-words which students spontaneously have to order under four categories: very good / quite good / rather bad / very bad. Students then compare their lists giving reasons. It's certainly a technique which relates to the vocabulary-oriented preparation and which is a very student-centred or personalised and therefore meaningful activity:

windy, hot, chilly, stormy, dry, warm, bright, frosty, dark, cool, clear, quiet, icy, cloudy, sunny, foggy, misty, rainy, snowy, freezing cold, unsteady, wet, drizzly, grey

As a second step, I dictate or present the extracts in two blocks and have students work as described above.

A

B

The rain has gone

I can see clearly now

None of the dark clouds

I can see all obstacles in my way.

It's going to be a bright day

It had me down

There's nothing but blue skies

I can make it now

Here is that rainbow

All of the bad feelings have disappeared

An example might read as follows:

I can make it now

It's going to be a bright day -

All of the bad feelings have disappeared.

The rain has gone -

It had me down.

None of the dark clouds -

I can see clearly now.

There's nothing but blue skies -

I can see all obstacles in my way.

Here is that rainbow -

I can make it now.

To give a better idea of the kind of language I extracted, here is part of the lyrics:

I can see clearly now

The rain is gone.

I can see all obstacles in my way.

None of the dark clouds

That had me down.

It's gonna be a bright, bright

sunshiny day.

It's gonna be a bright, bright,

sunshiny day.

Oh, yes, I can make it now

The rain is gone.

All of the bad feelings

Have disappeared

.

Here is that rainbow

I've been praying for.

It's gonna be a bright, bright,

sunshiny day.

Look all around.

There's nothing but blue skies.

Look straight ahead.

There's nothing but blue skies.

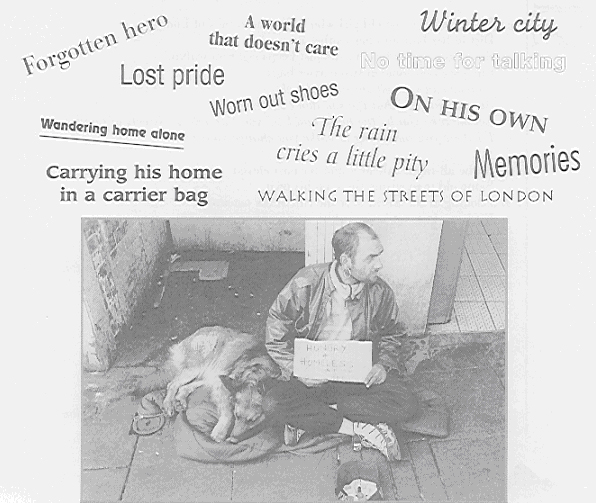

2 Topic-oriented listening or reading preparation using visuals

The following activity is a preparatory task for a song, but I could imagine it to be adapted to any kind of text suitable for this technique.

- Choose those parts of the text that could represent newspaper headlines.

- Write them in mixed order on a transparency or on the board and hand out a copy of a picture of your choice that relates to the topic of the text. You might want to prepare a photocopy of the headlines for each pair/group, including the picture as shown below.

- Dictate the following questions: If you were the author of the article, which of the headlines would you choose to match the picture? What topic could the article be about? What exactly does the author say about the topic or story, do you think? What subtitle or beginning of the article would you expect to read?

- Ask students to work in pairs or small groups and to choose 2 - 3 headlines that best match the picture. They should take notes on their answers and maybe write the beginning of the article which they are going to compare in class later.

- Students might also write some questions they would want to ask the author.

Here's an example to support the idea explicitly. The song 'The streets of London' by Ralph McTell is well-known and I therefore won't need to copy the lyrics. (They can be found on the Internet with the help of 'Google' search.) As a general warmer, I would ask students to tell each other what 'home' means to them. Or I might display various pictures of big cities like New York, Tokyo, London etc., or show one transparency of a similar picture in order to help students visualise the problems people living there are confronted with.

You will probably recognise that all the 'headlines' below are extracts taken from the song. The task lends itself as an introduction to the topic, it helps students get familiar with some of the language used in the song/text. The questions above can support speculation and discussion. As an additional question to the ones listed above you could dictate: What does the person in the picture most probably call his 'home'? Where and what is it like, do you think?

(texts and ideas are taken from 'Network Music Bar' by Silvia Stephan, Langenscheidt-Longman)

PERSONALISING LANGUAGE

part three: Effective and affective post-reading tasks

As in pre-reading tasks, where students are given the opportunity to use and work with parts of the yet unknown text, post-reading activities can achieve the same aim, namely to help learners express their personal opinion, feelings and ideas by even playfully dealing with the target language. The main difference is that in pre-reading tasks the extracts are chosen by the teacher, whether it be vocabulary, statements, particular phrases or structures. In post-reading activities, students can choose the parts themselves and explore language as shown in the examples below.

1 Headline poems

Imagine students have read a particular text and are familiar with its contents. The main aim of the following activity isn't necessarily to check comprehension, (although it might unconscously do), but to stimulate the students' creative skills, to help them develop a feeling for the target language, for the 'music', the rhythm and for the meaning it carries. Furthermore, this kind of task can motivate them in their learning by having fun at the same time as using the target language effectively. This doesn't necessarily imply that all students sitting in a class will enjoy it, but at least half of them will benefit in one or the other way. I recommend the following procedure.

- Decide whether the text you are going to read with your class can be exploited in the way suggested.

- Ask students to work in small groups and underline or copy as many 'headlines' they can discover in the text. You might have to help them find one or two examples by explaining what headlines generally consist of.

- Invite students to read and compare their 'headlines'.

- Ask students to try to write a 'poem' by choosing any of their 'headlines' in any order they like adding at least six to eight lines.

- Finally groups read their 'poems' to the class.

- Collect and type them up as students appreciate a printed copy of their 'work of art'. It gives them a feeling of importance and shows that their personal language production is valuable.

The text presented here as an example is part of a true story. I've used this technique with stories in particular as there are sequences students can follow more easily, although the outcome of the task, or the 'poem', isn't meant to be a copy of the story necessarily. The parts printed in bold are examples of possible 'headlines'. The underlined parts exemplify a 'headline' within a 'headline'.

The Singing Conductor

Baysee Rowe, 29, is a London bus conductor on the number 38 route, which runs from Victoria to Clapton Pond. He has been singing to his passengers for a number of years. His first single, Sugar Sugar, released on his own label, Double Decker, reached No 30 in the UK and No 1 in South Africa. He has four children, from five months to 11 years old, all of whom live with their mothers. He lives on his own in Leyton, east London.

He doesn't have much of a social life any more, but he doesn't get lonely. "With music you are never alone," he says. "Music is the best wife you could have, she never argues and she always pleases." He would like to be married but it just hasn't happened. All women want attention and he hasn't got that kind of time.

His flat is basically a recording studio. He has 15.000 pounds worth of recording equipment - he bought it piece by piece - but he doesn't own washing machine or a bed. It doesn't bother him. He is a late sleeper He just drags the sofa cushions onto the floor and throws a duvet over himself.

He isn't too bothered about foodeither. He thinks that musicians are terrible eaters because they just don't have the time. He spends the majority of his spare time composing. He writes down an idea on the back of a ticket, then comes home and puts it down on tape.

Here are some examples students might present:

It just hasn't happened

A London bus conductor

on his own

for a number of years.

Never argues,

always pleases.

A late sleeper,

not too bothered.

Married?

It just hasn't happened.

Musicians

Music is the best,

the best wife,

she never argues

,

she always pleases.

You are never alone.

Attention!

Musicians are terrible,

terrible eaters,

not too bothered about food.

Would like to be married -

just don't have the time.

Sugar Sugar

A London bus conductor

on the number 38 route

released

'Sugar Sugar',

piece by piece

on the back of a ticket.

His first single,

on his own label,

No 1 in South Africa.

Singing to his passengers

'Sugar Sugar'

for a number of years

on the number 38 route.

from Victoria to Clapton Pond,

(text and idea is taken from 'English Network Conversation' by Silvia Stephan, Langenscheidt)

2 Meaningful words

The first time I did the following post-reading activity was about 18 years ago. I remember the session very well and I still have the class in mind. To be very honest, it was a lesson I didn't have time to thoroughly prepare and the idea spontaneously cropped up while teaching. It was an intermediate class and it was quite a lengthy text. Although the terms 'student-centred' and 'sharing the responsibility', not to speak of 'personalising your coursebook', hadn't quite settled in my mind yet, I decided to ask students to read the text silently first. Nowadays, I would play some meditative music with it which obviously I didn't at that time. But let me introduce the procedure in steps:

- After a short warmer related to the topic, ask students to read the text silently.

- In pairs or groups of three, students underline or copy the words neither of them know, which means they first help each other find the meaning and only then ask the teacher for help.

- In their group, students choose and make a list of the 15 most important words related to the contents of the text. By that, they argue and talk about contents and meaning without you asking them comprehension questions.

- Ask groups to dictate their lists which you write on the OHP/board. A number of words will obviously overlap.

- Now ask the class to tell you as much as they know about the text using as many words listed on the OHP/board as possible. Cross out the words mentioned until none of them are left.

Since that lesson 18 years ago, I adapted this technique to different levels, altering parts of the procedure. Here's an alternative version I have used with lower- to upper-intermediate classes over the years. It has proved very effective but affective as well as students interpret contents and meaning very differently and need to argue in order to come to an agreement:

- Read the text with your students including an appropriate pre-reading task.

- In pairs, as a post-reading task, students choose and copy 10 words they find most relevant in regard to the contents.

- In groups of four, students then compare their two lists and reduce the number of words down to the ten most important ones. They can ask a secretary to take notes.

- Once groups are ready, hand out differently coloured A4-papers with the copy of the outlines of a flower, an animal or any kind of shape your students might like or might connect with the topic. The different parts of the object should be big enough to be filled with one or more words. For example, the stem of the flower should be drawn with two parallel lines or the petals in big circles.

- Groups fill the object with their ten words, placing them anywhere according to importance. They finally present their drawing to the class giving reasons for the placement of their words.

I've had classes who asked me to hang the 'flowers' on the wall which proves that they not only enjoyed but felt that the result of the lesson was important to them. Looking at the session from a critical point of view I can say that students were practising the four skills intensively, the visual, auditory and even the kinesthetic learner had their role to play and, above all, students were practising vocabulary by reading, writing and repeating words several times, relating them to a contents and giving them personal meaning. I do hope that students' long-term memory got filled with actions, voices, pictures, colours, feelings and words, of course, to be stored and called upon whenever necessary.

Silvia Stephan, teacher, teacher trainer and author, Offenburg, Germany

Please check the The Seconary Teaching course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the The English for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|