The Relationship between Language Anxiety and What Goes on Between the People in the Classroom

On being judged, being isolated and feeling out of control.

Anna Turula, PhD. Teacher trainer with the English Department, University of Bielsko-Biala, Poland. E-mail: anturul@poczta.onet.pl

Menu

Introduction/ Background

Preliminary results

Are we a happy family / A cooperative group

Am I a good parent / Am I a good teacher?

Is our home/classroom) a nice place to be in?

Teacher's Self-Reflection Questionnaire

Introduction/Background

Language anxiety is a common label Arnold and Brown (1999) use for the lack of confidence in oneself as a learner, uneasiness, frustration, self-doubt, apprehension and tension. It is described as related to language learning situations like tests (Bailey 1983 quoted by Ellis 1994: 480), assimilation of knowledge and skills (MacIntyre and Gardner 1994) as well as speaking and listening (Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope 1986, MacIntyre and Gardner 1994, Matsumoto 1989). However, as learning a language is almost always a social undertaking, it seems that additionally, there has to be some kind of mutual influence between such states of discomfort and frustration and what actually "goes on … between the people in the classroom" (Stevick 1980:4). In other words, language anxiety can be strengthened by how the teacher and peer students actually react verbally and non-verbally to the efforts an individual makes in order to learn, assimilate knowledge and perform.

In my study of the relationship between language anxiety and classroom dynamics (Hadfield 1992) I was particularly inspired by "The Confidence Book" by Davis and Rinvolucri (1990), which describes techniques which help build confidence in the classroom while looking at three inhibition-breeding aspects of the language classroom: being judged, being isolated and feeling out of control. This is why in my research carried out in the years 1999-2000 in 4 groups of adult beginners learning English and German in two private language schools in Katowice (Poland) I looked all the ways in which people can be judged. I investigated the following areas: teacher's error correction routines, ways of giving explanation, teacher's and peers' way of showing verbal and non-verbal (dis)approval), feeling isolated (territorialism in the classroom, distribution of turns, teacher favouritism) and feeling out out of control (learner autonomy, to what extent the lessons prepared the students for real life communication). The research was carried out by means of classroom observation with the use of a number of observation charts and scales devised for the purpose of my study while language anxiety was tested at the end of the observation period by means of the Anxiety Scale (McIntyre and Gardner 1994). I also examined such aspects of positive classroom dynamics as: collaborative learning, motivation, learner autonomy and experiential learning.

Preliminary results

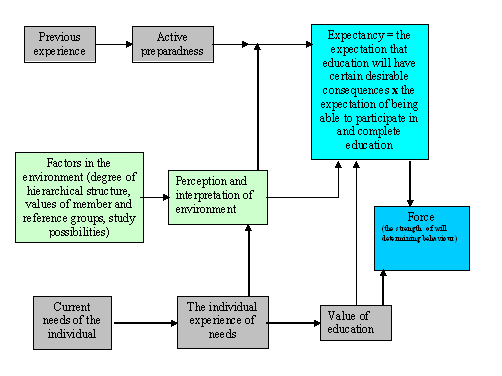

To start with, the findings of the research show a relationship between low language anxiety and steady motivation which Hadfield (1992) sees as an important element of positive classroom dynamics. In particular, the results I obtained confirm the validity of the Expectancy-Valence paradigm below (Rubenson in Cross 1981: 118).

Figure 11. Rubenson's Expectancy-Valence Paradigm (Cross 1981: 118)

Looking at the paradigm, we can say that our motivation in general and the drive to learn a language in particular, depends on two factors: our estimation of the attractiveness of the possible outcome of our activity (language learning in our case) as well as our confidence that the learning context is conductive to success. The results I obtained prove that the classrooms where two 'expectancy factors' ( the expectation that education will have certain desirable consequences and the expectation of being able to participate in and complete education) were lower, had higher anxiety scores. In the context of language classroom reality, the two expectations mean: the trust in being both in good hands and on the right track as well as the students' belief in their own ability. Therefore, it has to be stated that the first and very important inhibiting factor is the incompetent, untrustworthy teacher who offers classroom instruction seen by the students as substandard. Language anxiety in such a case is frequently reinforced if lack of professionalism coincides with ambitious learning objectives of the student. Another anxiety-breeding factor is low self-esteem of the learner resulting from both - the teacher's negative attitude or insufficiently positive attitude manifested in verbal and non-verbal reactions to the student's performance and choice of error correction. Such lack of learner confidence may further be strengthened if the student does not have a clear sense of achievement resulting from the teacher's negligence to monitor learner progress and give regular feedback. In addition to that, the observation made it clear that another important tension-breeding aspect of classroom dynamics is the feeling of isolation. It may result from the group's territorialism, sitting arrangements of the particular classroom or insufficient attention from the teacher and peer students. What is more, students feel anxious if isolated from the world of real communication. It could be observed that even a seemingly anxiety-free classroom, where risk-taking is low and production reduced to a drill, can breed anxieties associated with seeing oneself as unprepared for the challenge of true communication.

The third factor which seems to underly language anxiety which identified in the research is the lack of individual treatment of learners. Classrooms where teachers were unaware of or not interested in the learners' individual learning styles and did not allow their learners to show themselves to peer students as interesting and unique human beings were foiund to be most inhibiting. The inhibition resulting from the insufficient attention of the teacher was usually additionally reinforced if the teacher is not fair in his/her distribution of turns. The observation results lead to a number of practical implications. The first refers to teacher training at universities and colleges. It seems that in addition to the cognitive syllabus, the would-be teachers should be sensitized to the metacognitive and the affective aspects of the language classroom. They have to become aware that teaching methods are as important as good rapport in the classroom and language instruction has to be enriched by teaching how to learn. Secondly, as the competence of the teacher has been proved to be such an important issue, the teachers should be encouraged to take ongoing care of their professional development. Finally, the methodology syllabus - in addition to pedagogy training - has to incorporate elements of adult education. As the research amnong others showed, it seems striking that the observed teachers were almost totally unaware of the specific characteristics and needs of the adult learner. At the same time both, the aspiring and practising teachers should be encouraged to reflect on their own teaching with special regard to teacher routines, the rapport between people in the classroom and the role of the premises. As part of the research, I asked all the observed groups to specify what they thought and ideal teacher/group/classroom should be. The language they used was more reminiscent of parents, family and home than anything related to school and learning. If it is so, each teacher needs to ask him/herself the following questions - Are we a happy family?; Am I a good parent?; Is our home a nice place to be at? In fact, all three questions should refer to the above mentioned anxiety-breeding factors: being judged, being isolated and feeling out of control. As a result, the reflective teacher may want to look at themselves asking:

Are we a happy family / A cooperative group

The teacher must be aware that a language classroom, unlike both science and humanities classroom, is a place where the students need to invest their own time and energy and put a lot at stake. Language is a practical skill not just subject knowledge. As a result, learning a language implies practice and all attempts at production mean the risk of potential failure. However, failure is easier to bear when you are with friends. In turn, in order to like you people need to know you. And if people are to know you, you have to open and share yourself with others. Moskowitz (1978) provides further rationale for the humanistic classroom. If the language is to be learned, she argued, the content has to be personalised. If we are to communicate, we want to communicate what is of importance to us personally. The role of the teacher in establishing and maintaining positive rapport between students is very important. First of all, it is him/her who sets the initial "caring and sharing". That is why the questions a reflective teacher should ask him/herself are: "Do I share myself with my students?" "Am I frank and sensitive?", "Do I encourage and teach my students to personalise the content of the lesson?".

At the same time it is necessary for the teacher to realise that such openness may not be practicable in every group, with particular regard to teenage classes. Wilson (1999) claims that one of the best ways of scaring a young person is ask them to talk about themselves. In such a case personal interests instead of personal life is the path the teacher has to follow. Therefore "Do I find out from my students what they are interested in?", "Do I teach across the curriculum to get through to those who like maths, biology, literature?", "Do I let my students suggests lesson topics/ homeworks/etc.?" are another set of questions teachers need to ask themselves. Another skill necessary in the humanistic classroom is the ability to listen to other people. It is easier to overcome the apprehension associated with speaking in a foreign language if your audience is friendly. If the listeners are attentive and empathetic, it gives the speaker an additional morale boost.

Is it possible to teach empathy, though? First of all, teachers themselves can be models of empathetic listeners. There is a number of verbal and non-verbal signs showing that you are with the speaker and not deep in your thoughts. That is why, the teacher needs to ask him/herself: "Do I listen to my students attentively?", "Is there a constant eye-contact between me and the speaker?", "Do I try to avoid writing on the board, fixing equipment, etc. while a student is speaking?", "Do I try to avoid signs of impatience?", "If there is a need to interrupt, do I do it tactfully?". Apart from being the model of an attentive listener, the teacher can introduce the humanistic exercise into the classroom. Classroom Dynamics by Jill Hadfield (1992) and the Sharing and Caring in the Foreign Language Class by Gertrude Moskowitz (1978) contain a large number of examples of such games and tasks. Neuro-Linguistic Programming, with its "in your shoes" paradigm, is another source of excellent techniques in this area.

What people can and should be encouraged to share in the humanistic classroom are not only their personalities and interests, but also their learning techniques and strategies as well as doubts, problems or motivation decline. Rubin (1975) discovered that weaker students can learn from a good language learner. That is why such an exchange of ideas may encourage students try out successful strategies used by their peers. Therefore, another question a reflective teacher should ask is "Do I encourage metacognitive swapshops in my class?". The last factor preventing caring and sharing is class territorialism. Students like to stick to their seats, rarely change their place in the classroom and almost always work with the same partner. As a result, there may be people in the classroom who have never spoken to each other and sometimes do not even know each other's names. One answer is breaking up such pairs. Another, melee exercises, a number of which can be found in Hadfield and Moskowitz. Therefore the questions at this stage will be "Do I deal with territorialism in my class?".

Am I a good parent / Am I a good teacher?

Another focus of the self-reflection should be oneself as a teacher. Good parents can be respected and the respect gives the child the feeling that they are in good hands and thus safe. Good parents listen to their children. Good parents love everybody the same. And finally, good parents be-wing their children. As an old saying goes we do not have children for ourselves but for the world. Consequently, a good teacher is primarily a good professional. A lot has been said about how important is the person of the teacher in motivating students and raising their self-confidence, the relationship is most clearly shown by Rubenson's Expectancy-Valence Paradigm. That is why "What do I do for my own professional development?", "Are my classes interesting/varied/creative?" are the questions teachers need to ask themselves at this stage. Secondly, the teacher has to be a good audience. The question of attentive listening has already been discussed. In addition to this, a good attentive teacher listens to the students' voice in all matters concerning the organisation and management of the course. That is why regular student evaluation is a must. "Do I ask my students for their opinion about the course?" is the question which needs to be asked here.

Another problem is the treatment of students that is not quite just. The research has once again made it obvious that teacher favouritism is a serious problem in almost every classroom. That is why the very important questions will be: "Do I treat all students equally?" "Do I give each of them the same number of turns/ amount of approval/ opportunity for self-correction/ respect/ patience?", "Do I rearrange the classroom/ Am I on the move to be in equal eye contact with all the students?", "Don't I have the tendency to turn always to the same people while asking questions/ telling anecdotes?". Finally, the question of be-winging the children/students introduces the idea of learner autonomy. However, we cannot expect our students to be autonomous before we tell them how to be self-dependent.

First of all a self-dependent learner is the one who has been shown a number of various ways and can choose the one that suit him/her best. That is why the already mentioned exchange of ideas and strategies is so important. Secondly, in order to learn without the teacher's assistance the student needs to know how (s)he learns best which means that (s)he has to be aware of his/her linguistic intelligence and it is the teacher's role to sensitize the student to the problem. It may be carried out by means of straightforward presentation or by presenting different types of exercises for all kinds of intelligences in the classroom. Finally, if the student is to take on some of the responsibility for his/her learning, the teacher has to be ready to share it in what can be called autonomy spoon-feeding. It will be a step-by-step involvement of students in smaller and bigger decisions concerning their own learning. Not only, as it has already been said, need the students evaluate the course. They may also participate in decisions concerning homework assignment, furniture arrangement, problems that need to be discussed. The teacher should encourage them to feel free to take the initiative in those areas. At the same time it is the teacher's role to build up the students' confidence to make them believe they can be successful learners. That is why, apart from a friendly attitude and frequent approval, the teacher has to be very tactful in his/her error correction and explanations, both of which can be highly judgemental. For the same reason, instead of explicit instant treatment of both the problem areas, it is better to allow room for self-correction and as often as possible corrction should be redirected to the class. The questions that need to be asked at this stage are "Do I inform my students about different kinds of linguistic intelligence?", "Do I encourage my students to plan their learning, to experiment what, how, where, when, etc. they learn best?", "How do I explain?".

Is our home/classroom a nice place to be in?

The appearance of the classroom can be controlled only to a certain extent. Teachers usually do not have much influence on the financial standing of the school. What, however, is within the teacher's control is making sure students sit in a way enabling eye-contact, the room is aired before the lesson and possibly, students ideas about how the classroom should look like are taken into account and their work is exhibited. Because what makes us feel at home is - much more than luxury - the belief that the place we are in is ours. All the above questions can become the basis of the Teacher's Self-Reflection Questionnaire, whose aim would be to help educators critically examine their own teaching procedures. This new tool may be applied in a number of areas. Firstly, it can be used as the reference material for teacher training sessions whose aim is to encourage reflective teaching as well as sensitise the ongoing and, possibly, the future educators to the metacognitive and the affective in the language classroom. Secondly, the questionnaire may be applied on the teacher-to-teacher basis - either in mentoring or in peer observation programmes - as a means of the analysis of the classroom dynamics of an individual lesson. Finally, a tool of this kind may be an important instrument for individual professional development because, as hopefully has been illustrated by the present dissertation - all teachers should work to become better professionals and more sensitive and understanding human beings.

Teacher's Self-Reflection Questionnaire

ARE WE A HAPPY FAMILY?

1) DO I SHARE MYSELF WITH MY STUDENTS?

2) AM I FRANK AND SENSITIVE?

3) DO I ENCOURAGE AND TEACH MY STUDENTS TO PERSONALISE THE CONTENT OF THE LESSON?

4) DO I FIND OUT FROM MY STUDENTS WHAT THEY ARE INTERESTED IN?

5) DO I TEACH ACROSS THE CURRICULUM TO GET THROUGH TO THOSE WHO HAVE A FLAIR FOR MATHS, BIOLOGY, LITERATURE?

6) DO I LET MY STUDENTS SUGGEST LESSON TOPICS/ HOMEWORK/ ETC.?

7) DO I LISTEN TO MY STUDENTS ATTENTIVELY?

8) IS THERE AN EYE CONTACT BETWEEN ME AND THE SPEAKER?

9) DO I AVOID WRITING ON THE BOARD/ FIXING THE EQUIPMENT/ ETC. WHEN A STUDENT IS SPEAKING?

10) DON'T I MANIFEST IMPATIENCE?

11) IF THERE IS A NEED TO INTERRUPT DO I DO IT TACTFULLY?

12) DO I ENCOURAGE EXCHANGE OF IDEAS, EXPERIENCE, STRATEGIES?

13) DO I DEAL WITH TERRITORIALISM IN MY CLASS?

AM I A GOOD PARENT?

14) WHAT DO I DO FOR MY OWN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT?

15) ARE MY CLASSES INTERESTING/ VARIED ? AM I CREATIVE?

16) DO I TREAT ALL MY STUDENTS EQUALLY?

17) DO I GIVE EACH OF THEM THE SAME NUMBER OF TURNS/ AMOUNT OF APPROVAL/ OPPORTUNITY FOR SELF-CORRECTION/ RESPECT/ PATIENCE?

18) DO I REARRANGE THE CLASSROOM/ AM I ON THE MOVE TO BE IN EQUAL EYE CONTACT WITH ALL THE STUDENTS?

19) DON'T I HAVE A TENDENCY TO ALWAYS TURN TO THE SAME PEOPLE WHILE ASKING QUESTIONS/ TELLING ANECDOTES?

20) DO I INFORM MY STUDENTS ABOUT DIFFERENT KINDS OF LINGUISTIC INTELLIGENCE?

21) DO I ENCOURAGE MY STUDENTS TO EXPERIMENT WHAT/ HOW/ WHEN/ WHERE THEY LEARN BEST?

22) DO I SHARE CLASSROOM RESPONSIBILITY WITH MY STUDENTS?

23) HOW DO I CORRECT MY STUDENTS?

24) HOW DO I EXPLAIN?

IS OUR HOME A NICE PLACE TO BE AT?

25) HOW CAN I MAKE MY STUDENTS FEEL THAT THE CLASSROOM BELONGS TO THEM?

References

Arnold J. & H.D. Brown. 1999. "A Map of the Terrain". In J. Arnold (ed)Affect in Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

Cross, K.P. 1981. Adults as Learners. Increasing Participation and Facilitating Learning. St.Francisco, Washington, London: Jossey-Bass Publishers. .

Davis, P. and M. Rinvolucri 1990. The Confidence Book. Pilgrim Longman Resource Books.

Ellis, R. 1994. The Study of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford University Press.

Hadfield, J. 1992. Classroom Dynamics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horwitz, E.K., M.B. Horwitz & J. Cope. 1986. "Foreign language classroom anxiety". Modern Language Journal 70, pp. 125-132. .

MacIntyre, P.D. and R.C. Gardner. 1994. "The Subtle Effects of Language Anxiety on Cognitive Processing in the Second Language" in Language Learning 44, 2 pp. 283-305.

Matsumoto, K. 1989. "Factors involved in the L2 learning process". JALT Journal pp. 167-192. .

Moskowitz, G. 1978. Caring and Sharing in the Foreign Language Class: A Sourcebook of Humanistic Techniques. Rowley/Massachusetts: Newbury House.

Rubin, J. 1975. "What the Good Language Learner Can Teach Us". TESOL Quarterly 9, pp. 41-51.

Stevick, E.W. 198O. Teaching Languages. A Way and Ways. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Please check the The Creative Methodology course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the The Expert Teacher course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the The Secondary Teaching course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the The Skills of Teacher Training course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the The Teaching Large Classes Humanistically course at Pilgrims website.

|