Rating and Writing: Two Sides of a Coin?

Christophe Ruehlemann, Munich, Germany

The concept of Learner Autonomy strongly advocates learner involvement in evaluation. Underlying this approach is the belief that evaluation skill is a skill in its own right, independent from the other four skills. On the other hand, a widespread belief in teacher common rooms suggests that skilled writing and skilled evaluating go hand-in-hand just as unskilled writing and unskilled evaluation are believed to do. This paper aims to examine the validity of these conflicting beliefs. The study is based on learner and teacher co-evaluation of letters of application written and peer-evaluated by Munich secondary school learners. Analysis of the data only partially confirms the assumption that writing and evaluating writing are globally correlated abilities in that correlation was found only for medium to high writing skills levels, but not for low levels. However, the analysis lends support to the assumption that evaluation skill is independent from writing skill.

Introduction

Learner autonomy is generally understood as the "capacity to assume reflective responsibility for one's own learning" (Little, Simpson and O'Connor 2002: 54). The central question in research into Learner Autonomy, then, is how teachers can help learners develop responsibility. Scharle and Szabó (2000) argue that "[l]earner responsibility can really only develop if you allow more room for learner involvement" (p. 5) , with learner involvement being achieved by "[t]ransferring roles to the learner" (p. 9). Obviously, one of the foremost teacher roles is the role of evaluator. Accordingly, research on Learner Autonomy advocates involving learners in evaluation (for example Little 1999, Dam 2000, Scharle and Szabó 2000). Learner involvement in evaluation becomes even more central when it is expanded from involvement in formative evaluation (assessment for learning by reflecting or self-reflecting on how a learner can improve) to involvement in summative evaluation (assessment of learning by reflecting on what a learner actually can and can't do), as was recently argued (s. Rühlemann 2003).

This call for learner involvement in formative and summative evaluation, however, proves problematic on two counts. Firstly, it rests on the tacit assumption that evaluation skill is independent from the four skills of writing, reading, speaking and listening. If evaluation skill were not seen as independent from the other skills, there would be no point in encouraging, for example, 'poor' speakers or writers to evaluate their own or their peers' speech or writing since their evaluation would likely be 'poor' as well. Instead, involvement in evaluation would have to be restricted to skilled speakers and writers only. Such a restriction, however, is not imposed by the concept of Learner Autonomy. It follows, then, that the call for learner involvement in evaluation builds on the assumption that evaluation skill is independent from the other skills - an assumption that has been taken for granted but to my knowledge not tested so far. Secondly, this tacit assumption is in stark contrast to the assumption which many teachers intuitively lean to, that effective learner evaluation of, say, writing presupposes a high level of writing skill on the part of the evaluator and, conversely, that learners whose writing is flawed will produce flawed evaluation of writing. In this view, rating and writing are seen as two sides of a coin.

That is, both research and practice converge in regard to high achievers, who are thought likely to do a good job of evaluating themselves or their peers. They diverge, however, in regard to 'the rest'. Can learners that display weaknesses reasonably be trusted to provide instructive evaluation? What if the conclusions they arrived at and the advice they gave their peers as part of formative peer-evaluation were utterly misleading? Can we really trust learners regardless of their skills level to provide evaluation that will foster rather than misguide and thus hinder learning? Rather than transferring the role of evaluator to all learners irrespective of their skills level, would we not have to restrict this role transfer to 'good' learners only, for, surely, it is they who know what makes, for example, 'good' writing? None of these questions have to my knowledge been answered as yet in research into Learner Autonomy. Obviously, the need to address these questions becomes even more pressing if learners are given a say in summative evaluation which may result in grades and affect the learners' school careers.

In other words, research into Learner Autonomy has postulated the usefulness of involving learners in evaluation but failed until now to provide empirical proof of the feasibility of this approach. In order for involving learners in evaluation to be feasible and conducive to learning, evaluation skill would have to be proven independent from the other four skills. Only then could, say, a struggling writer be sensibly expected to give a peer-writer useful feedback that will help the peer improve his or her writing. Moreover, only then could concerns be alleviated that involving learners in evaluation will wreak havoc rather than foster learning.

The study reported in this paper specifically looks into how evaluating skill interrelates with writing skill. The research question which the study addresses, then, is the following: Is evaluation skill correlated to writing skill, as is widely assumed in staff rooms, or is evaluation skill independent from writing skill, as is presupposed in the concept of Learner Autonomy?

Three groups of secondary school learners were asked to write a letter of application. Their letters were co-evaluated by a peer and the teacher using a set of previously defined criteria. Their scores as authors and evaluators were then compared.

Analysis of the data only partially confirms the assumption that writing and evaluating writing are globally correlated abilities in that correlation was found only for medium to high writing skills levels, but not for low levels. However, the data lends support to the assumption that evaluation skill is independent from writing skill, thus justifying the call for learner involvement in evaluation. Given the limited data size, the findings need however be substantiated by more large scale research.

Method

Criterion-referenced co-evaluation (CCE)

As the label 'co-evaluation' suggests, the teacher's evaluation was combined with a peer-evaluation each. The criteria were operated in a 'labour sharing' fashion, i.e., the peer-evaluators and the teacher shared the same set of criteria. The co-evaluation was performed 'blind', i.e., with neither party knowing the other party's evaluation.

Involving the learners in evaluation presupposes equipping them with the means necessary for this transfer of roles to be successful. The means exploited in CCE is reference to criteria (see Brown and Hudson 2002 for an account of the theoretical framework of criterion-referenced testing, as opposed to norm-referenced testing). Thus, a core presupposition in CCE is that for learners to achieve valid evaluations, using evaluation criteria effectively is quintessential (see Lenz and Schneider 2002). This presupposition is grounded on the following considerations:

" manageability: criteria help the learners break demanding evaluation tasks into manageable 'units';

" orientation toward standards: criteria help the learners base their evaluations on academic standards of achievement rather than personal likes and dislikes.

" learning opportunity: because criteria correspond to academic standards of achievement, using criteria in self- or peer-evaluation provides the learners with an opportunity to internalise these very standards (see also Tomlinson 2005).

" formative feedback:criteria identify the evaluees' weaknesses and strengths in detail and may thus foster autonomous learning.

Participants

Three groups of tenth-graders (16 to 17 years of age) in their final year attending a Munich secondary modern school wrote letters of application. Group a, consisting of 10 learners, wrote their texts in the school year 2000/1, while Group b (16 learners) wrote theirs in the school year 2002/3, and Group c (26 learners) wrote theirs in 2003/4. Thus, the number of participants whose evaluation and writing scores could be compared is 52.

Procedures

The learners were asked to write a letter of application in response to a job advertisement found on the web. They were told to write about the three prompts given in the instructions and to add two further aspects of their own choosing which explain why they thought they were the best person for the job. The instructions read as follows:

You have found the following job vacancy on the website of The Council of the European Union:

The Council of the European Union

is looking for an

English-speaking secretary ( m / f )

Please apply now. Give details about the following points:

" Education

" knowledge of languages

" computer skills

Add and describe two further aspects which explain why you would be the best person for this job.

|

You have decided to apply for this job. Please write about all the points given in the advertisement, find a suitable beginning and ending and connect the sentences in a proper way. You don`t have to write any addresses. :

Seven criteria were used: coherence (sequencing of topics), cohesion (linking devices), content (ideas), convention (sociolinguistic appropriateness), conviction (effort), accuracy (grammatical, lexical and spelling correctness) and variety (grammatical and lexical diversity).

The learners had been familiarised with the criteria extensively. So, for example, awareness of the importance of coherence in texts had been raised by reconstituting jumbled texts, and cohesion had been taught by comparing identical texts with and without linking devices such as discourse markers (see Witte and Faigley 1981 and Zamel 1983 for useful advice on how to teach coherence and cohesion). Convention had been tackled by juxtaposing the different stylistic rules that hold for formal letters to unknown addressees and informal emails to friends. Variety had been pointed to by contrasting letters featuring high rates of lexical and structural redundancy to letters displaying a broad range of lexical and structural choices. Further, judging content required the peer-evaluators to examine whether all points given had been addressed and elaborated in good measure. No additional teaching/learning efforts were thought necessary for the criteria of accuracy and conviction. Accuracy, for a start, corresponds to the principle of 'correctness' that all learners of a foreign language are likely to be sufficiently familiar with from form-focused classrooms. Conviction, finally, is the criterion that is least measurable objectively despite the fact that it is extremely common in assessments; it requires peer-evaluators to gauge the amount of effort the author invested on the basis of empathy.

For each criterion a maximum score of 5 points could be given, resulting in a 35-point maximum score an author could achieve. The minimum score was 1 point; with the learner evaluation and teacher evaluation maximally differing by 4 points per criterion, the total rating difference could maximally reach the value 28. Figure 1 displays the co-evaluation grid:

| learner evaluation: |

teacher evaluation: |

co-evaluation: |

| criteria |

points |

| coherence |

|

| cohesion |

|

| content |

|

| convention |

|

| conviction |

|

| accuracy |

|

| variety |

|

|

| criteria |

points |

| coherence |

|

| cohesion |

|

| content |

|

| convention |

|

| conviction |

|

| accuracy |

|

| variety |

|

|

|

| total: |

total: |

total: |

Figure 1: Co-evaluation grid

The achievement as authors (a-scores) were measured by calculating the total score given by the teacher (see column 'teacher evaluation' in Figure 1). That is, the higher the score, the higher the achievement as author. The maximum score that could be achieved was 35. The achievement as evaluator (e-score), by contrast, was measured by calculating the total rating differences between a learner's peer-evaluation of another learner's letter and the teacher's evaluation of the same letter (see column 'rating differences' in Figure 2). Thus, the higher this score, the lower the learner's achievement as evaluator (as perceived by the teacher). The maximum score was 28. In other words, while a-scores were measured along a positive 35-point scale, e-scores were measured along a negative 28-point scale. In the analysis below, the resulting interrelation of a-scores and e-scores is investigated.

Two limitations, however, need to be considered first. For a start, in establishing a learner's e-score the teacher's evaluations are taken as standard. Clearly, even the best teacher's evaluations can be 'wrong'. So, teachers' assessments cannot be thought infallible. It is hard to see suitable alternatives: peer-learners can even less reliably provide standard evaluations, 'outsiders' such as colleagues, heads of department, principals, or university staff are all teachers in disguise, and involving them in the dyadic classroom is often difficult, and, finally, respective computer software is not around. In this study, the teacher's evaluations are thus taken not as infallible but simply as sufficiently reliable and the most readily available data that the learners' data can be compared with. Secondly, e-scores and a-scores are taken as indicators of a learner's evaluation skill and writing skill respectively. This is of course not to suggest that a single pair of scores will suffice to fully reflect a learner's abilities. To achieve this, many more such pairs of scores would be prerequisite. Thus, the ability referred to in this paper just reflects the ability as evidenced in the CCE of a letter of application.

Results

Central to the concept of Learner Autonomy is the call for involvement of learners in evaluation. As noted above, this call builds on the assumption that even those learners who do badly in, say, writing may nonetheless do well at evaluating their own or their peers' learning progress, that is, it is believed that evaluation skill is a fifth skill, as it were, independent from the other four skills. This assumption can be termed the 'independence hypothesis'. In opposition to this tacit understanding, a widespread belief among teachers suggests that a high level of writing ability necessarily entails a high level of evaluation ability while lack of writing skills is seen as concomitant with lack of evaluation skill. In this view, rating and writing are interpreted as correlated abilities regardless of ability level. This view can be summarised as the 'global-correlation hypothesis'. Both hypotheses are examined below.

Let us start with a comparison of two learners' achievements as authors and evaluators respectively, learner A(Group a) and learner F(Group b).

Learner A(a)'s ability to peer-evaluate effectively can be seen critically (see Table 1). Her peer-evaluation differed from the teacher's by 11 points altogether; her evaluation was higher (indicated by the + symbol in Table 1) than the teacher's on four criteria (coherence, cohesion, accuracy, and variety, with cohesion seeing a 3-point, and variety a 4-point, difference), lower (indicated by the - symbol) on two criteria (convention and conviction), and matched the teacher's only once (content). The high degree of rating differences suggests a low level of evaluation skill. However, does it go hand-in-hand with a low level of writing skill?

Table 1: Rating differences learner A(a)

| coherence |

cohesion |

content |

convention |

conviction |

accuracy |

variety |

+ |

- |

total |

| 1+ |

3+ |

0 |

1- |

1- |

1+ |

4+ |

9+ |

2- |

11 |

Table 2 shows the ratings by peer-evaluator K(a) and by the teacher of learner A(a)'s letter of application. Interestingly, her writing skills regarding those criteria that had seen the highest rating differences in her evaluation of a peer's letter - cohesion, where a 3-point rating difference had occurred, and variety, with a maximal difference of 4 points - seemed impeccable with 5-point scores by the teacher and 4-point scores by the peer on both criteria. As the ratings concerning the other criteria attest, this learner's text was 'good' on all counts. Hence, the learner's rating and writing skills clearly diverge.

Table 2: Co-evaluation of learner A(a)'s letter

|

coherence |

cohesion |

Content |

Convention |

conviction |

accuracy |

variety |

| Peer |

4 |

4 |

5 |

3; |

4 |

4 |

4; |

| Teacher |

5 |

5 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

However, other learners' writing and rating seemed equally well developed. An example is learner F(b). Contrary to his peer, who awarded four 3-point and three 4-point scores, the teacher's evaluation was noticeably more favourable, with two 3-point, two 4-point, and three 5-point ratings (s. Table 3). Thus, this learner's writing was considered 'satisfactory to good' (by the peer) and 'good' (by the teacher) respectively.

Table 3: Co-evaluation of learner F(b)'s letter

|

coherence |

cohesion |

Content |

Convention |

conviction |

accuracy |

variety |

| Peer |

3 |

3 |

4 |

3; |

3 |

4 |

4; |

| Teacher |

5 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

Learner' F(b)'s evaluative skills proved to match these writing skills in that two 2-point, three 1-point differences, and even two complete rating agreements occurred. Given the relatively low total of 7 points rating difference, his peer-evaluation can be regarded as 'good' altogether (s. Table 4).

Table 4: Rating differences learner F(b)

| coherence |

cohesion |

content |

convention |

conviction |

accuracy |

variety |

+ |

- |

total |

| 0 |

1- |

0 |

2+ |

1+ |

2+ |

1+ |

6+ |

1- |

7 |

How did rating and writing generally interrelate?

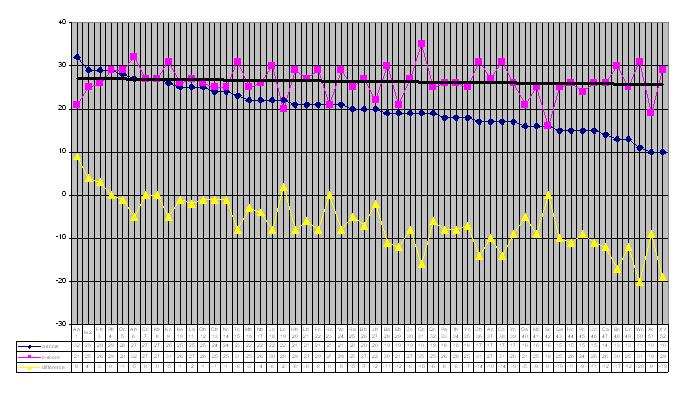

Figure 2 illustrates how the achievements of 52 participants both as authors of a letter of application and as peer-evaluators of another learner's letter of application interrelate. As noted above, a-scores were measured along a positive 35-point scale, while e-scores were measured along a negative 28-point scale. These divergences in polarity and maximum score make it difficult to compare both scores. Therefore, to facilitate comparison, e-scores were converted from a 28-point to a 35-point scale and inverted from a negative scale to a positive one; resulting decimal numbers were rounded to the nearest integer. So, for example, the negative e-score of seven points by which learner F(b)'s peer-evaluation of another learner's letter differed from the teacher' (s. Table 3) were converted into a positive e-score of 26 (s. Figure 2 below). Thus, e-scores and a-scores can be compared directly.

Figure 2 represents these a-scores and e-scores as graphs. A-scores are sorted in descending order. The almost horizontal straight line represents the a-scores trend. The graph in the lower half of Figure 2 represents a-score and e-score differences. The table below the figure lists all participants as well as scores and score differences. The participants are numbered in terms of their a-score rank.

Figure 2: a-scores, e-scores, and scores difference; all groups

Figure 2 allows for a number of important observations.

If writing and rating were indeed correlated at all levels of writing skill, as the 'global-correlation hypothesis' suggests, a-scores and e-scores would show a clear tendency to coincide or at least descend in parallel. This is plainly not the case. Instead, the trends of both scores clearly diverge with the a-scores trend distinctly pointing downward while the e-scores trend remains almost level throughout.

Likewise, if we look at a-score and e-score differences, we clearly note that a-scores and e-scores tend to deviate from each other in the majority of cases. Scores coincide only five times (learners P(b), G(c), K(b), R(c), and S(c)). They deviate five times by 1 point (learners O(c), K(a), O(b), C(b), and N(c)), four times by 2 points (learners L(a), L(c), and K(b)), and twice by 3 points (learners (F(b) and M(b)). That is, even if we admit a generous 3-point deviation for there to be correlation, e-scores and a-scores correlate only 15 times out of 52. On the other hand, scores differences above three points abound. On average, e-scores and a-scores differ by 7 points. Differences by 8 points occur seven times, differences by 9 points five times, and differences of 10 or above 10 points 14 times. So, it would appear that score correlation is clearly too infrequent to support the global-correlation hypothesis. That is, the data does not lend support to the widespread belief among teachers that successful writers are just as likely to be successful evaluators of writing as struggling writers are likely to be struggling evaluators of writing.

However, the correlation hypothesis need not be discarded altogether. For, intriguingly, all the score pairs that have been found to display correlation (allowing for a 3-point deviation) are medium to high score pairs. The only exception is learner S(c) whose scores, though 'mediocre', coincide completely with both scores being 16 points. All the remaining 14 correlated score pairs are found in the left half of Figure 2, that is, they are found among the 27 best authors with a-scores being 20 points or above. Except learner S(c), who ranks 42nd in Figure 2, all those learners with whom e-score and a-score coincide achieved predominantly high a-scores ( ranking 4 sup>th,

, 7 sup>th, 8 sup>th, and 23 sup>rd respectively). The learners with whom the scores differ by 1 point rank 5 sup>th,,10sup>th, 12 sup>th, 13 sup>th, and 14 sup>th. Differences by 2 or 3 points are equally found with the 'better half' of a-scores. Conversely, all the 14 learners whose scores differed by 10 or more points are found on the right hand side of Figure 2; that is, they are found with learners whose a-scores were below 20 points; the most prominent examples being learners W(c) and X'(c), ranking 50 sup>th and 52 sup>nd, whose differences reach 20 and 19 points respectively.

What do these observations suggest? It would seem that, contrary to the global-correlation hypothesis, which assumes correlation regardless of writing skill level, writing skill and evaluation skill seem to be partially correlated in that correlation takes place with medium to high a-scores but not with low a-scores. That is, the data support the assumption shared by research and practice that we can justifiably expect effective writers to perform effective evaluation of writing.

A third crucial observation can be made in regard to evaluation skill. Contrary to the sloping a-scores, the e-scores trend remains almost level throughout. This is due to the high number of high e-scores coupled to low a-scores. The most striking example thereof is learner G(c), ranking 31st as author, who achieved a maximal 35-point e-score but only a mediocre 19-point a-score. Other obvious examples include learners B(c), W(c) and X'(c), ranking 48th, 50sup>th, and 52 sup>nd, , who reached high e-scores (31 and 29 points respectively). Indeed, out of the 25 learners with a-scores below 20 points (ranks 28 to 52) six learners achieved 30-point e-scores or above, and, more importantly, 20 learners achieved 25-point e-scores or higher. On the other hand, high e-scores were also found concomitant with high a-scores; thus, for example, out of all 20-point or above-20-point a-scores (ranks 1 to 27) 21 were 25 points or more. So, high e-scores were clearly found among 'good' and 'poor' authors alike.

How can we make sense of this observation? In the present study, e-scores clearly proved independent from a-scores; that is, the learners' evaluation was effective although their writing may have been less so, and vice versa. Surely, it is tempting to generalise from this finding and conclude that evaluation skill is not tied to writing skill but independent from it. The data base this study draws on is too small in size to permit such a far-reaching claim. However, the finding seems to suggest that both skills may be independent from one another. Clearly, large-scale comparisons of e-scores and a-scores are needed to conclusively support this hypothesis. If independence of e-scores from a-scores should prove consistent in future research, this finding would be of considerable importance, because it would help justify the call for involvement of learners in the evaluation of their own learning, which is at the heart of the concept of Learner Autonomy. Only if learners can achieve high levels of evaluation skill independently from their levels of achievement in the four other skills can they justifiably be trusted to arrive at reliable and conclusive evaluations of their own, or their peers', learning progress.

Conclusion

The aim of the present study was to examine the central assumption in Learner Autonomy that evaluation ability is independent from the other four skills, an assumption which is in stark contrast to the wide-spread belief that writing and rating writing are globally correlated abilities. The study was limited to examining the relationship between evaluation and writing skills.

Based on data from CCE of letters written by Munich tenth-graders, analysis of the interrelation of e-scores and a-scores did not lend support to the 'global-correlation hypothesis', that is, the presupposition that writing skill goes hand-in-hand with evaluation skill and lack of writing skill is concomitant with lack of evaluation skill. The two skills proved to correlate only partially since matches of evaluation ability and writing ability were found much more frequently with skilled writers than with less skilled ones. Moreover, proficiency at evaluating was found with skilled and unskilled writers, suggesting that evaluating ability might be seen as independent from writing ability - a finding that adds to the rationale of involving learners in the evaluation of learning, a key concern of Learner Autonomy.

Given the limited number of participants and scores the study is based on, these findings, however, need to be substantiated by more large-scale research before they can claim general validity. Given the prominence that research into Learner Autonomy accords to learner involvement in evaluation the need to investigate the interrelationship of rating and writing is pressing. If the initial findings reported should be supported by future research, the consequences would be far-reaching: it would be possible to allay fears that involving learners in evaluation will hinder learning rather than foster it, and more teachers would feel encouraged to give their learners a say in evaluating their learning.

References:

Brown, J. D. and T. Hudson. 2002. Criterion-referenced Language Testing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Dam, L. 2000. 'Evaluating autonomous learning' in B. Sinclair, I. McGrath and T. Lamb. (eds.). Learner Autonomy, Teacher Autonomy: Future Directions. Harlow: Longman

Lenz, P. and G. Schneider. 2002. 'Developing the Swiss model of the European language portfolio' in Council of Europe. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Case Studies. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing. 68-86

Little, D., B. L. Simpson, and F. O'Connor. 2002. 'Meeting the English language needs of refugees in Ireland' in Council of Europe. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Case Studies. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing. 53-67

Little, D. 1999. The European Language Portfolio and self-assessment. Strasbourg: Council of Europe (DECS/EDULANG (99) 30)

Rühlemann, C. 2003. 'Sharing the power: classroom research into co-evaluation.' Englisch 4/03: 136-144

Rea-Dickins, P. and K. Germaine. 1992. Evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Scharle, A. and A. Szabó. 2000. Learner Autonomy. A guide to developing learner responsibility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Tomlinson, B. 2005. 'Testing to learn: a personal view of language testing'. ELTJ 59:1, 39-54

Witte, S. P. and L. Faigley 1981. 'Coherence, cohesion and writing quality'. College Composition and Communication. Vol. 32/2: 189-204

Zamel, V. 1983. 'Teaching those missing links in writing'. ELT Journal 37/1: 22-29, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Please check the The Testing course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the The Skills of Teacher Training course at Pilgrims website.

|