'Humanising' - what's in a word?

Philip Kerr, Belgium/UK

Philip Kerr is a teacher trainer and author who lives in Brussels. His most recent project has been a series of coursebooks for adults and young adults called Straightforward (Macmillan, 2005 - 2007).

Menu

Introduction

Humanising and humanizing

Humanising / Humanizing humanists

Humanist Psychology

Humanising in 1999

Humanism in ELT: 1980 - 1999

Humanising language teaching today

Since you're reading a magazine called 'Humanising Language Teaching', the likelihood is that you are a language teacher or in some way connected with the world of language teaching. There's also a fair chance that you think that 'humanising' (whatever that may be) language teaching is a good thing. But 'humanising' is a word with an interesting, career, and deserves a slightly closer look.

You only need to think of the word's opposite - 'dehumanising' - with all its negative connotations, to understand that anything that is 'humanising' is a good thing. Check out 'humanising' in any corpus, or google it, and you'll see that the most frequent associations are those where something that is impersonal (e.g. a computer programme), distant or remote (e.g. distance education) or inhumane (e.g. a social system) can be improved through a process of 'humanising'. The word has unavoidable, in-built connotations that are strongly positive and, as such, falls into a large category of words that determine our emotional response to them. In everyday discourse, words like 'community', 'democratic' or 'natural', for example, are typically used, either consciously or unconsciously, to confer approval on the thing that is being referred to. Conversely, words like 'terrorist', 'extremist' or 'weapons of mass destruction' are chosen to elicit a negative emotional response. It doesn't matter if these words are poorly-defined; what counts is the emotional punch. For a fascinating study of how words are used with emotional intent in the world of politics, I recommend Unspeak by Steven Poole (Little Brown, London 2006).

Rather like some of the words listed above, 'humanising' is problematic because it means different things to different people. Typical dictionary definitions talk about 'rendering human or humane; imparting human qualities to; making a process or system less severe or easier for people to understand'. Although these enable us to get the general gist of the word, they also raise questions. How do we define what is human or humane? Which human qualities are we referring to? For which people do we want to make things easier to understand? And, crucially, how can things be made easier or softer? Such questions cannot be answered without reference to specific contexts and to specific cultures. In order, therefore, to deepen our understanding, we need to look more specifically at the contexts and cultures in which the word is used.

If you check out how the word 'humanising' is used in contemporary English, you will notice that 'humanizing' with a 'z' ('US' spelling) is significantly more common (by an order of about 5 to 1) than 'humanising' with an 's' ('UK' spelling). This is, in part, because more users of English around the globe use American spellings than British. This includes the British themselves, who are increasingly using a 'z' in words ending in /α \ ζ/ or /α \ ζ \ |/, such as apologise / apologize, generalise / generalize or realise / realize. If you're interested, you can get an A - Z list of words ending in -ize (from abolitionize to womanize) by typing [*ize] in the search facility at www.onelook.com. Although the list includes a handful of items like 'capsize', 'prize' or 'seize' (where the final -ize is not a verbal suffix), the vast majority are verbs that can be spelled -ise or -ize.

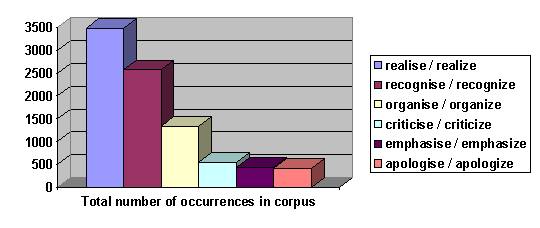

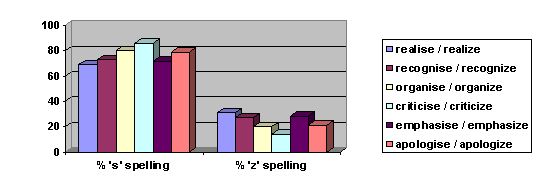

How do the British decide which spelling to use when they are faced with a choice? The best place to find out is by taking a look at some of the most frequent -ise / -ize words in a recent corpus of written UK English.

Broadly speaking, the figures suggest that about 75% of the time, the British prefer the 's' spelling and, if I am in any way representative of native British users of the language, they use the two spellings pretty interchangeably, even using both within the same text. A native British user is unlikely to feel that anything is out of the ordinary if they encounter the words 'humanize / humanizing' with a 'z'. The same is not true, however, of a non-British user of the language who encounters 'humanise / humanising' with an 's'. In other words, in the context of a piece of writing with an international readership (such as this magazine), 'humanising' with an 's' is a marked form that can draw attention to the Britishness of the writer.

The verb 'humanise / humanize' is relatively rare in English, with only a handful of occurrences in the large corpus that I referred to. Much more common (by an order of about three to one) are the related words 'humanist', 'humanistic' and 'humanism'. If you were to come across the verb 'humanise / humanize' in an everyday context (for example, the following phrases that were thrown up by Google: Humanize the Earth!, Welcome to Humanize Toronto or humanise the interface), you probably wouldn't make any connection with humanists or humanism. But in an educational context, things are rather different. Humanism has had such a profound influence on education in the last five centuries that it is impossible not to make some sort of mental connection between the words 'humanising / humanizing' and 'humanism / humanist(ic)', quite apart from the fact that they have seven letters in common.

It is probable that the words 'humanism / humanist(ic)' in English derive from Ariosto's (1474-1533) coinage 'umanista', which he used to describe 'a student of human affairs or human nature'. In many countries, we continue to study 'Humanities' or a related word (e.g. in Belgium, where I live, French speakers study 'humanitÚs'). The traditions of Renaissance humanism continue to influence educational practice in many parts of the world. Coming slightly more up to date, the American school of educational humanism that flowered in the nineteenth century gave a new lease of life and a slightly different meaning to the word.

It was in America, too, that 'humanism' hit the international big-time again in the twentieth century. In contemporary educational contexts, mentions of 'humanism' or 'humanist(ic)' are most likely to refer to the school of psychology, called 'Humanist Psychology', that emerged in the 1950s.

Humanist Psychology, closely associated with the work of Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, offered a more holistic approach to psychology than that provided by prevailing practices, and focussed on the 'whole person' (another phrase that it is both culturally-bound and difficult to disapprove of, despite its frustrating vagueness). In clinical terms, Humanist Psychology is closely connected with counselling and notions of 'self-help'. In research terms, it leans towards qualitative analysis (another one of those phrases!) rather than the quantitative iron-clad boot of statistics. Its insistence on the uniquely human aspects of human existence, on the importance of considering wholes rather than parts, struck a popular chord and a series of almost evangelical writings catapulted Humanist Psychology into the mainstream. In the last ten years or so, the glamour of this school of psychology has worn off somewhat, eclipsed by the recent rapid advances in evolutionary psychology and descriptions of brain architecture.

In the world of language teaching (or, at any rate, in some of the discourse communities of the world of language teaching), humanism of the Rogerian kind made an indelible mark. When this magazine was established in 1999, its first editor, Mario Rinvolucri, and many of the early contributing authors, made very clear their personal identification with this Rogerian humanist tradition. In the first year, major articles were entitled 'Are we ready for holism?' and 'Whole or hole', and the first major article of all, 'What is Teacher development?', by Paul Davis, established a clear link with the Teacher Development Special Interest Group (SIG) of IATEFL and its newsletter, which, for years, had been showing a marked interest in counselling, co-counselling, the role of affect in learning and teaching and other areas associated with Humanist Psychology.

In the very particular context of English language teaching in Britain in 1999, the use of the word humanising could not fail to be associated with humanist(ic) approaches to language teaching as they were conceived at the time. What exactly were these approaches? A recent reference book (Thornbury, S. An A - Z of ELT (Macmillan, 2006) provides an excellent summary:

The term humanistic describes learning approaches that assert the central role of the 'whole person' in the learning process. Humanistic approaches emerged in the mid-twentieth century partly as a reaction to the 'de-humanizing' psychology of behaviourism, but also as a counterbalance to exclusively intellectual (or cognitive) accounts of learning, such as mentalism. The titles of some of the key texts on humanistic education give a flavour of its concerns: Carl Rogers' On Becoming a Person (1961) and Freedom to Learn (1969); Abraham Maslow's Towards a Psychology of Being (1968) and Gertrude Moscowitz's Caring and Sharing in the Foreign Language Class (1978). Some basic tenets of humanistic education include the following:

- Personal growth, including realizing one's full potential, is one of the primary goals of education.

- The development of human values is another.

- The learner should be engaged affectively (i.e. emotionally) as well as intellectually

(-> affect).

- Behaviours that cause anxiety or stress should be avoided.

- Learners should be actively involved in the learning process.

- Learners can - and should -take responsibility for their own learning.

Why, then, was this magazine called 'Humanising Language Teaching' as opposed to 'Humanist (or Humanistic) Language Teaching' - which would have made it rather more clearly identifiable? And was this decision in any way connected with the choice to go with the marked British 's' rather than the American 'z'? Here, after all, was a new magazine, manifestly and strongly influenced by the 1960s American wave of psychological humanism.

The choice of title indicates, I think, a desire to be broader in appeal. If you're already into humanist(ic) approaches, this is obviously a magazine for you. Indeed, if you google either 'humanist language teaching' or 'humanistic language teaching', this magazine will come up on the first page of the search. But 'Humanising language teaching' was much more all-encompassing and did not present the potential dangers of 'Humanist' or 'Humanistic', because, by 1999, these two words had already accumulated a certain amount of problematic baggage.

By the end of the 1990s, the word 'humanist(ic)' had clearly become problematic in the world of language teaching, or at least in certain small regions of the world of language teaching, such as the contributors to English Language Teaching Journal (eltj.oxfordjournals.org), probably the most influential ELT journal in the UK. You can buy the archives of ELTJ on CD-ROM, and the handy search function allows you to trace the history of words like 'humanist', 'humanistic' and 'humanising' in the twenty years leading up to the establishment of 'Humanising Language Teaching'. In the early 1980s, use of these words was rare and passing, but in 1984 and 1989, articles by Stevick (On humanism and harmony in language teaching ELTJ 38/2 April 1984) and Underhill (Process in humanistic education ELTJ 43/4 October 1989) put humanist(ic) approaches firmly on the map. By 1992, Prodomou (What culture? Which culture? ELTJ 46/1 January 1992) had suggested that humanistic approaches were becoming an orthodoxy.

The honeymoon of humanist(ic) approaches was short-lived. The problem, essentially, was that humanism in ELT had become associated with a constellation of contentious topics such as psychodrama, Gestalt therapy or NLP. More contentious, still, were the attempts by advocates of aromatherapy or shamanism, for example, to hitch themselves to the humanist(ic) bandwagon. Only two years after writing an article (The mother tongue in the classroom: a neglected resource? ELTJ 41/4 October 1987) in which he referred approvingly to the use of mother-tongue in the language classroom as 'humanistic', David Atkinson launched a scathing attack (Humanistic' approaches in the adult classroom: an affective reaction ELTJ 43/4 October 1989) on 'humanistic' approaches, which he resolutely kept in inverted commas throughout, preferring 'humanistic' to 'humanist' tout court, perhaps because the -ic suffix can add a certain derogatory spice if said in the right way.

For the next ten years, contributors to the journal argued the toss on humanistic approaches, but with articles entitled Towards less humanist English teaching (Gadd, N. ELTJ 52/3 July 1998), it was clear that this particular word family had become something of a liability. Meanwhile, the rest of the world continued using 'humanist' and 'humanistic' in a much more general sense. A check on common collocations in the large corpora throws up words like 'democratic', 'moral' or 'secular'. So, while a relatively small number of (predominantly native-speaker) ELT people were arguing about the relevance of Rogerian humanism to language teaching, most of their colleagues (who had other things to do, perhaps, than read ELT magazines and journals, and who may have been completely unaware of potential Rogerian connotations) were using the word 'humanist', if at all, to mean something very different, probably undefined, but generally positive.

Mario Rinvolucri, the founder of this magazine, has said that in the 1980s he was reluctant to describe any teaching as 'humanistic', feeling that this would have been too big and arrogant a claim, although his circumspection has decreased in the last 25 years (personal communication). Paradoxically, then, humanism is both present in and absent from the title of this magazine. It was, I think, a clever choice. As the years have gone by and as the magazine has evolved, the contents of the magazine have shown a marked shift away from a Rogerian-humanist kind of humanising, towards a looser, more general interpretation of the word. The publishers of the magazine, Pilgrims, are proud of what they describe as their 'Humanistic Approach'. Their website describes this in the following terms:

- Effective teaching and learning engages the whole person - the mind, the body and the heart

- The learner is the central person in the act of learning

- Creativity, involvement and enjoyment are the essential elements for lifelong learning.

I suppose I might quibble with some of the details here. I'm not sure that the metaphor of the heart is one that I would go along with, and I suspect that 'lifelong learning' is frequently a red herring of wishful thinking. But the key concepts of 'engagement' and 'learner-centredness' are surely ones that nobody would dispute, in theory if not always in practice. Described in these terms, 'humanistic' is basically synonymous with 'good' and, by extension, 'humanising' means 'making better' or 'improving'...all of which conveniently brings me back to where I started. Precisely how we have made or could make things better in our classrooms is what most of the articles in this magazine (this one being something of an exception) are about. My thanks go out to the publishers for continuing to offer this service to you and me for free.

Please check the Humanising Large Classes course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Skills of Teacher Training course at Pilgrims website.

|