Fostering Language Acquisition: Task Based Lesson and Vehicular Use of FL/SL in the Italian Education System

Barbara Sinisi, Italy

Barbara Sinisi studied German and English literature at Roma Tre University and in 2005 she received a PhD in German Literature at Pavia University. From 2005 to 2008 she worked as a German adjunct professor in various universities. From 2006 to 2008 she also attended the SSIS-Toscana (Postgraduate Specialization School for Teachers of Secondary Schools) and currently she works as a high school English teacher. She wrote many papers about literature, linguistics and second language acquisition. Her major research interests in linguistics and second language acquisition are: SLA (theories of second language acquisition), using literature in the FL/SL class both as a linguistic and a cross-cultural medium, implications of text-linguistics in teaching a FL/SL, vehicular use of the FL/SL to teach a FL/SL for specific purposes, drama techniques to teach a FL/SL.

E-mail: barbarasinisi@hotmail.com

Menu

Introduction: The role of the task within the language class

CLIL and task based approach

What is CLIL and why fostering this approach within the language class

Lucky numbers: My CLIL experience at Scuola Città Pestalozzi

Literary competence and task based literature class

What is literary competence and how to foster it within the language class

Art and Beauty in John Keats’ poetry: My experience at Liceo Internazionale

Conclusions

Learning is finding out what you already know.

Doing is demonstrating that you know it.

Teaching is reminding others that they know it just as well as you.

You are all learners, doers, teachers.

(Richard Bach)

The idea of this paper is derived from my personal experience with the SSIS teaching practice at SSIS-Toscana during the years 2006-2008. At that time I had the opportunity to observe foreign language lessons (both in English and German) taught by more experienced colleagues and to teach classes myself in schools of different levels 2. The training at SISS gave me the opportunity to reflect about second language acquisition in the Italian context, in which frontal lesson still seems to be the most accepted methodology.

Thus, the present work starts from the observation that there is a discrepancy between the widely accepted methodological framework, i.e. communicative and task-based language lesson, and the real practice in Italian schools. What I noticed during my teaching practice was the treatment of the foreign language as something “outside” the learners, something talked about rather than used for communication: the focus is mostly on grammar forms, which have to be memorized and formulated correctly. And since students conceive English as a subject to be learnt rather than a language for communication, this leads to a lack of interaction. Yet, Tricia Hedge points out that, in order for the lesson to be effective, there must be a balance between global exposure to the language and analysis of linguistic items, so that both global learners and analytic learners can be involved (Hedge, 2000, p. 18). This principle seems to be ignored by the majority of the Italian language teachers, who usually base their lessons on the deductive analysis of grammatical items and on the presentation of lists of new vocabulary, to be learned by heart. As for the teaching of literature, which is a compulsory part of second language class in Italy, Italian education system also seems to lack in an inductive approach to both content and language. Students are usually given lectures about biography and works of the major writers of the canon and expected simply to memorize those notions so that they can repeat them verbatim when the teacher asks. This approach however, puts students, who have a more global attitude towards learning and who like to learn by discovery, at a disadvantage.

Nevertheless, scientific literature about SLA underlines that the nature of the input provided to learners is a quite important issue. As Krashen has reasonably pointed out, the input must be comprehensible (Krashen, citated in Hedge, 2000, p. 11.). Krashen’s comprehensible input hypothesis states that language is acquired when learners receive input from messages which contain language a little above their existing understanding and from which they can infer meaning (Carter & Nunan, 2001, p. 89-90). By contrast, in my personal experience, the input provided to the learners by the teacher seemed to be not ‘comprehensible’ enough: the students seemed not to understand it and not to take advantage of it. This, in my opinion, depends on several reasons: on the one hand, the input provided was too abstract and seemed not to have any relationship with the real experience of the students in the every day life, on the other hand, it was a teacher-directed input that rarely takes initiative or allows contributions from the learners.

As far as the language acquisition is concerned, the lack of a comprehensible input inhibited the learners from processing the language features and thus from comprehensible intake: there was no possibility for the learners to “assimilate language to their interlanguage system” (Hedge, 2000, p. 12). Thus, if interlanguage is a developing system, a system given by the process of “hypothesis making and testing” in which the learners “make sense of language input and impose a structure on it” (Hedge, 2000, p. 11), then the input given to the students must be conceived not in terms of content transmission, but in terms of tasks.

Stella Cottrell refers to Piaget’s concept of assimilation and accomodation in order to explain the process of learning. Piaget argues that equilibration (that is to say a new and further stage of knowledge after the intake of a new input) occurs in three stages:

- equilibrium: a pre-existing stage of satisfaction with our way of thinking

- disequilibrium: a dissatisfied awareness of limitations in our existing ways of thinking

- a more stable equilibrium: we move to a more sophisticated way of thinking that overcomes the limitations of our previous thinking (Piaget citated in Cottrell, 2001, p. 21)

In accordance with this formulation, we must assume that the role of the teacher is to create opportunities for “disequilibrium”, in order to achieve a progress in the student’s way of thinking. In the longer term this can lead to a reconceptualising of the learning process which takes the learners to new and deeper levels of understanding. SLA theoretical research shows that this process is directly connected to the opportunities the students have to be involved in meaningful tasks performed actively during the lesson.

As Tricia Hedge points out, “communicative language teaching sets out to involve learners in purposeful tasks which are embedded in meaningful contexts and which reflect and rehearse language as it is used authentically in the world outside the classroom” (Hedge, 2000, p. 71). Similarly, Edmondson underlines that “input as a category only becomes theoretically interesting when it moves into interaction”, that is to say: “it’s only as interaction that input is critically relevant for language development” (Edmondson, 1999, p. 185). Likewise, Stella Cottrell sees the learning by doing paradigm as a way for the students to transform “routine knowledge”, which is tied to specific contexts, into “conceptual knowledge”, which is transferable to new situations (Cottrell, 2001, p. 21), thus creating long term acquisition.

In other terms, as the constructivist psychology points out, to have real acquisition, an active role of the students during the language lesson must be fostered: there is a need to move away from a “declarative and explicit” learning process by creating “procedural, implicit and holistic” learning situations (Anderson, cited in Even, 2003, p. 104). It is what Wolff refers to as a switch from “instruction” to “construction” in the learning process: learning is seen as a creative process of meaning “construction” instead of content transmission, the teacher as a facilitator instead of an instructor (Wolff, 1997).

Starting from these both theoretical and practical considerations, I decided to base my teaching practice of the second SSIS year on activities in which the focus was on a vehicular use of the target language and on the communication within the class. This implied that:

- the focus was on the meaning and not on the form

- the content had to be determined by the learners who were speaking or writing

- there had to be a negotiation of meaning between the speakers

- the communication had to be based either on an information, reasoning or opinion gap (Hedge, 2000, p. 58-60).

This paper is the description of task-based activities applied to two different realms: the study of the technical language and the study of literature, i.e. the two most relevant fields of second language acquisition in the Italian education system, both in technical and in humanistic high schools (with reference to this point, see also: Balboni, 2002, p. 138-152).

One of the most significant teaching experiences I had during the teaching practice my SSIS course, as far as the nature of the provided task is concerned, was using the CLIL at the experimental scuola media (11-13 years olds) Scuola Città Pestalozzi 3 in Florence.

As defined on the CLIL Compendium website: “CLIL refers to any dual-focused educational context in which an additional language, thus not usually the first language of the learners involved, is used as a medium in the teaching and learning of non-language content” (see: www.clilcompendium.com/). Basically, this means teaching a non-linguistic content through the medium of the foreign language. Thus, CLIL aims to create an improvement in both the foreign language and the non-language area competence, general categories being motivational and cognitive impact of the enterprise, and the linguistic and methodological utilisation of the non-language content material. The purpose for learners is to acquire language in a naturalistic way through the study of other subjects (Lauder, 2007).

In the Italian school system CLIL is implemented as a set of projects meant to increase the amount of language didactics in the school, for example through team teaching during the afternoon lessons in the scuola media (Eurydice 2006). In fact, it enables languages to be taught on a relatively intensive basis without taking over an excessive share of the school’s timetable. Moreover, it is inspired by important methodological principles established by research on foreign language teaching, such as the need for learners to be exposed to a situation calling for genuine communication (Bowler, 2007).

As far as the didactical principles are concerned, the use of English in a CLIL context represents a change in perspectives within the English classroom, for the following reasons:

- English is used throughout the lessons, hence has an altogether different role as means of communication

- CLIL contexts foster a natural acquisition of language in opposition to the EFL context

- English is used for a wider range of functions: to negotiate, to disagree, to ask authentic questions

- CLIL fosters a student-to-student interaction in English

- Students adopt the role as skilled users of English rather than of English learners

In brief, integrating language and content makes the use of English more ‘real’, interesting and meaningful by offering a variation to the language driven approach and by giving the pupils the opportunity to use English as a tool to investigate and describe (Bowler, 2006). It moreover enables social, cognitive, psychological and emotional development by involving high thinking skills (ability to make hypotheses, predictions and observations) and by appealing to distinct ‘intelligences’ (with reference to this point, see also: Gardner, 1991).

Insofar CLIL embodies the idea of a student centred approach in language teaching, by fostering the emotional involvement of the pupils through problem solving activities and meaningful tasks to accomplish. Also social skills are fostered because of the recourse to cooperative learning among the students. As far as the pragmatics are concerned, CLIL means studying language in context, with attention to the social dimension of communication and a focus on interaction in the classroom rather than second language learning (with reference to this point, see also: Balboni, 2002, p. 195-205.)

My CLIL experience at Scuola Città Pestalozzi was a five hour teaching unit, which was part of a cross-curricular project in a second year class about “Lucky Numbers” 5. It was taught as a team with the class English teacher and the math teacher. The general aims of the enterprise were, as far as the mathematical content was concerned, to promote the acquisition of practical skills in addition and multiplication of natural numbers and including effective problem solving through discovering regularities. As for the language skills, the general objectives were to foster a natural and task-based approach to the acquisition of the language, and to promote communication within the class. Social skills were also included because we aimed at promoting cooperative learning through group and pair work, and at fostering different learning styles.

In our original plan, by the end of the lesson the students should have been able not only to generate a sequence to discover if a number was lucky or not and to compare different solving procedures related to lucky numbers, but also to express hypotheses and describe regularities about lucky numbers in English, to talk about superstitions in English, and to create a web-site in English about the activity.

The strong point of the experience was the idea of combining the study of mathematical content with the contrastive study of cultural topics (like superstitions), all in a context of natural and task-based language acquisition.

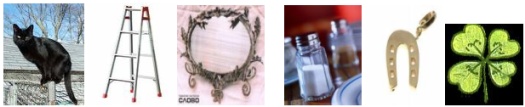

⇛ LEAD-IN: SUPERSTITIONS:

Thus, the lesson started with a lead-in activity about superstitions. We gave the students some flash cards representing different issues of superstition in different cultures, then we asked them to think about their pictures and decide whether they bring good luck or bad luck. They could sort their pictures and stick them either on a poster with the title “lucky” or on another one with the title “unlucky”. The visual aids and the sticking activity were useful to get the students involved in the activity and to appeal to their visual and kinaesthetic intelligence.

After having stuck the pictures, the students received some definitions written on paper strips that would help them become familiar with the English word for each superstition item. While taking turns, they had to stick each definition next to the corresponding picture.

Black cat: brings bad luck

To walk under a ladder: brings bad luck

To break a mirror: 7 years of bad luck

To spill salt: brings bad luck

Horseshoe: brings good luck

Four-leaved clover: brings good luck

Horn: brings good luck

To touch wood: brings good luck |

Thus, we introduced the topic by asking questions like: “Do you think that breaking a mirror brings good or bad luck?”, “Do you agree that walking under a ladder brings bad luck?”, “Is a black cat in your culture a lucky or unlucky omen? Do you think it is the same in other cultures?”.

After having introduced the topic starting from the personal experience of the students we moved on to pose the mathematical problem about “lucky” and “unlucky” numbers. This first step, however, was very important to create expectations about the topic among the students and to raise their attention, both because it was an involving activity in which they were active and because it started from the world they already knew. As far as the communication is concerned, the activity was based on reasoning and opinion gaps, so that the students were motivated to use English in order to express their ideas and points of view.

⇛ MAIN ACTIVITY 1

As a second step, together with the math teacher, we proposed a definition of “lucky numbers”, once again by working inductively with the students expectations and predictions. We started by asking general questions, such as: “Do you think 17 is a lucky or unlucky number?”, “What about 13?”, “Do you have your own lucky number?”, “What do you think a lucky number is?” . Thus, we introduced the mathematical definition of “lucky numbers”:

| “Choose a number. Square each of its digits and add the squares to get a second number. Square the digits of the second number and add the squares to get a third number. Continue this way to get a sequence. If the sequence ends up in 1, the original number is called lucky. If not - it is called unlucky.” |

I read the definition of a “lucky number” aloud and asked the pupils to concentrate on the mathematical procedure while listening. Then I read the definition once again, slower and in steps. Meanwhile the math teacher approached the procedure step by step on the blackboard, calculating the sequence of a number the class chose.

After that, in pairs the pupils tried to build a sequence taking as an example the numbers 13 and 17, in order to find out whether they are lucky or not. One student read the definition step by step and the other followed the procedure adhering to the instructions of his partner. Then they swapped. At the end, the class discussed the results of the activity in plenary and one pair showed the sequence on the board.

Here again, this inductive approach to mathematical content not only made the math lesson more interactive, but also created the conditions for real communication and fostered high reasoning skills by creating a situation of information and reasoning gap.

⇛ MAIN ACTIVITY 2

During the following lesson the students were asked to practice the mathematical procedure in groups. The class was divided into 5 groups: every group received 20 numbers, for which they had to write the correct sequence and find out if they were lucky or not. The very aim of the activity was to practice the procedure by analysing the first 100 numbers. During the activity they were also requested to work out operative rules to find ways of using one sequence to complete the others and to predict in advance whether a number will be lucky or unlucky. During the activity they were supposed to speak English as much as possible. I circulated in the classroom to monitor their use of language, while the math teacher monitored the mathematical procedure.

⇛ DISCUSSION

At the end of the activity, in Italian, the class discussed the operative rules the groups had found out as how to predict the result of a sequence. When the class agreed on a rule, the teacher wrote it on the board and the students copied it in their copy book.

⇛ LANGUAGE FOCUS

During the third lesson the focus was once again mainly on the language. In pairs the students revised the technical vocabulary related to the operative rules they have found in the lesson before by doing a matching exercise. Then they checked the results in plenary.

|

Match the rules below with their Italian equivalent:

- When the addition generates a loop the number is unlucky.

- When the addition generates a number of which we already know the sequence we can stop.

- All the multiples of ten refer to the procedure of their first digit.

- Ogni multiplo di dieci, dopo il primo passaggio, rientra nel percorso che indica la cifra della decina.

- Quando nella somma si arriva a un loop il numero è sfortunato.

- Appena in un percorso si arriva ad una somma che conosciamo ci possiamo fermare.

|

Then the class was divided into the same groups as in the previous lesson. Taking turns every group dictated to the class its numbers, saying whether they are lucky or unlucky. All the students meanwhile completed a grid, colouring lucky numbers in yellow. When dictating, the students were supposed to use the formula: “first row, first column: 1 – lucky/unlucky”.

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

| 11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

| 21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

| 31 |

32 |

33 |

34 |

35 |

36 |

37 |

38 |

39 |

40 |

| 41 |

42 |

43 |

44 |

45 |

46 |

47 |

48 |

49 |

50 |

| 51 |

52 |

53 |

54 |

55 |

56 |

57 |

58 |

59 |

60 |

| 61 |

62 |

63 |

64 |

65 |

66 |

67 |

68 |

69 |

70 |

| 71 |

72 |

73 |

74 |

75 |

76 |

77 |

78 |

79 |

80 |

| 81 |

82 |

83 |

84 |

85 |

86 |

87 |

88 |

89 |

90 |

Once they have completed the grid, the students are asked to make a hypothesis on possible regularities using the vocabulary they have learned. At present no regularity has been found in order to predict the occurrence of a lucky number: the aim of the activity is to let the student develop hypothesizing skills and to let them practice the vocabulary they have learnt.

⇛ FOLLOW-UP: WEB-SITE PLANNING

As a last step of the teaching unit, we wanted the students to reflect on the whole experience and we asked them to plan a web-link in English for the school web-site in which the activity was described. In groups the class planned the web-site. Every group was supposed to focus on one single aspect:

- definition, procedure and example

- description of the activity in class

- operative rules

- hypotheses on possible regularities

- myth of the lucky numbers – a fairy tale

|

In order to facilitate the production of the texts we provided the students with a list of words, expressions or sentences, which could be used to describe the activity:

What is a lucky number? What is an unlucky number?

lucky unlucky

A lucky number is... an unlucky number is...

How do you proceed to meet a lucky number?

During Maths/English lessons we found lucky and unlucky numbers.

Do you think 13 is lucky?

What about 17?

Is your birthday lucky or unlucky?

First/second/third... column

First/second/third... row |

At the end of the activity we collected the texts and edited them, together with the students. Then we discussed in general the order in which they had to appear on the web and the layout of the site.

In conclusion: the whole experience was very successful both for linguistic and pedagogical reasons. As far as the overall class management and general formative aims are concerned, it is worth noting that through the use of different types of input it has been possible to foster different learning styles within the class and to involve all the students in the activity. Moreover, by working in pairs and in groups the students experienced peer teaching and cooperative learning. As far as the language is concerned, the students used English as a vehicle of information and as a means of communication. By accomplishing different tasks, based on information, opinion and reasoning gaps, they experienced the language as useful for real communication. They were motivated in the acquisition of linguistic devices by the need to communicate and exchange meanings. At the same time, they improved their linguistic competence by learning new vocabulary and new expressions related to a specific technical branch of math. Thus, the students acquired the language in a natural environment without focussing on the process of learning new linguistic items. They also saw the immediate results of their linguistic performance (work management, meaning negotiation, information exchange and knowledge sharing) and could immediately re-use the language items they had learned by producing a web-site.

The idea of working inductively on literature in my English teaching practice was mainly due to my previous experience with literature classes in Germany. During the second SSIS year I had the opportunity to do part of my teaching practice abroad, in a “Gymnasium” (the German equivalent of a liceo, 10-18 years olds) in Ludwigshafen. There I observed not only foreign language classes, but also German classes, and I taught a two hour lesson in German literature in a twelfth grade (17 years olds) 6. What I observed and also practiced was a different approach to literature in which the teacher fosters students’ autonomous reasoning on the literary text. I noticed that this kind of approach created motivation among those students who like to learn through discovery and gave them the basis for autonomy in approaching a literary text. These are the reasons why I decided to put this approach into action in my English teaching practice in the Liceo Internazionale Machiavelli in Florence.

The teaching of literature is a complementary and an essential element for language teaching in the curriculum of many high schools in Italy. It is seen as an important feature of a holistic education. In fact, according to Gillian Lazar, literature should be used with the language learner for many different reasons:

- It is motivating material, exposing students to complex themes and unexpected use of language

- It encourages language acquisition, exposing students to authentic language

- It gives the students access to the cultural background of the people whose language they are studying

- It expands students’ language awareness, exposing them to a sophisticated use of the language

- It develops students interpretative abilities, stimulating high thinking skills (hypothesising, inferring, anticipating, generalising)

- It educates the whole person, stimulating the imagination, developing critical abilities and increasing emotional awareness (Lazar, 1997, p. 14ss.)

Thus, literature-based instruction gets learners deep into the best of language and has them actively involved in the learning process 7. Literature speaks directly to the emotional development of learners, as well as to their interests, needs, and concerns. Furthermore, through interacting with good literature, learners develop their ability to use higher-order thinking skills, to solve problems, and to arrive at generalisations to support or reject their hypotheses. In other words, they develop their “literary competence”, that Lazar, together with Culler, defines as “an implicit understanding of, and familiarity with, certain conventions which allow them to take the words on the page of a play or other literary works and convert them into literary meanings” (Lazar, 1997, p.12) 8.

In order for this to be real, indeed, literature should be taught, in my opinion, differently from the way it is usually taught in Italy. As I have already mentioned, the current practice in Italy is the deductive explanation by the teacher of the main events of the author’s biography, his literary production, and the main stylistic and thematic features of relevant literary movements. Working on the text means mainly translating it roughly into Italian. This reduces the motivation to study the literature in the original.

On the other hand, as I saw in Germany, through an inductive, task-based approach to literature 9, the learners construct their own conceptualizations and find their own solutions to problems, mastering autonomy and independence (Cornett, 2007, p. 94ss.). Moreover, they are encouraged to draw on their personal experiences, feelings and opinions. This helps students to become more actively involved both intellectually and emotionally in learning English, and hence aids acquisition.

My experience at Liceo Internazionale Machiavelli in Florence (14-18 years old students of an international high school) was a four-hour teaching unit in a fifth class on the topic “Art and Beauty in John Keats’ Poetry”. The lesson was based on the idea of working inductively on poetry, by fostering reasoning skills among the students (making and checking hypothesis). It also aimed at introducing the topic (the relationship between Art and Beauty in John Keats poetry) through the reading and analysis of two of his most famous poems: Ode on a Grecian Urn and La Belle Dame sans Merci. My major aim, as for the literary competence, was that students could grow autonomous in the approach to a literary text, so that, by the end of the lesson, they could be able, by working inductively, to recognise and analyse the same topic also in other poems by the same author.

As for the language skills, the lesson aimed at promoting communication within the class by fostering peer learning, knowledge-sharing and confrontation among the students. Thus, I wanted to create the conditions for authentic communication among the students in a context of reasoning, information and opinion gap (respectively, when they analysed the poems, when they shared information about them and when they discussed a possible interpretation).

Thus, I let the students work inductively on the language and content of the texts. I tried to contextualise the results of this work within the stylistic and poetic features of the period, and by using the texts as a tool for encouraging students to draw on their own ideas and opinions, I also tried to combine what Gillian Lazar recognises as the three main approaches to using literature with the language learner: a language-based approach to literature, literature as content, and literature for personal enrichment (Lazar, 1997, p. 11ss.).

The teaching unit was organised in two subsequent lessons of two hours, each one focused on one poem: the first on Ode on a Grecian Urn and the second on La Belle Dame sans Merci. The two lessons had almost the same structure:

⇛ LEAD IN:

I started with a visual input in plenary by showing the class a picture connected to the poem we were going to analyse and asked the students to describe what they saw. This phase was useful in order to anticipate some vocabulary and to create expectations about the poem.

I went on with an acoustic input: I played a CD in which the poem was read by a native speaker. This phase was useful for the students to get familiar with the pronunciation of unknown words, and with the melody and rhythm of the poem.

⇛ MAIN ACTIVITY 1

Then, I proposed a scanning activity on the text. As far as the first poem is concerned, the students in pairs had to list all the elements in the first (stanzas number 1, 2, 3) and in the second scene (stanza number 4) that describe the carvings on the urn. Finally they had to try and draw the two scenes: this was useful to visualize the content of the poem and to involve the students with a funny activity by appealing at their visual intelligence.

ODE ON A GRECIAN URN

1.

THOU still unravish'd bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fring'd legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

2.

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear'd,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal—yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love; and she be fair!

3.

Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed

Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu;

And, happy melodist, unwearied,

For ever piping songs for ever new;

More happy love! more happy, happy love!

For ever warm and still to be enjoy'd,

For ever panting, and for ever young;

All breathing human passion far above,

That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy'd,

A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

4.

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest,

Lead'st thou that heifer lowing at the skies,

And all her silken flanks with garlands drest?

What little town by river or sea shore,

Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel,

Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn?

And, little town, thy streets for evermore

Will silent be; and not a soul to tell

Why thou art desolate, can e'er return.

5.

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say'st,

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,"—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. |

As for the second poem, while reading, the students had to focus on the plot by doing an exercise in which they had to reorder the main events narrated in the poem.

LA BELLE DAME SANS MERCI

1.

O what can ail thee, knight at arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has wither'd from the lake,

And no birds sing.

2.

O What can ail thee, knight at arms,

So haggard and so woe-begone?

The squirrel's granary is full,

And the harvest's done.

3.

I see a lily on thy brow

With anguish moist and fever dew,

And on thy cheeks a fading rose

Fast withereth too.

4.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful, a fairy's child;

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

5.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She look'd at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan.

6.

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A fairy's song.

7.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna dew,

And sure in language strange she said—

I love thee true.

8.

She took me to her elfin grot,

And there she wept, and sigh'd full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

9.

And there she lulled me asleep,

And there I dream'd—Ah! woe betide!

The latest dream I ever dream'd

On the cold hill's side.

10.

I saw pale kings, and princes too,

Pale warriors, death pale were they all;

They cried—"La belle dame sans merci

Hath thee in thrall!"

11.

I saw their starv'd lips in the gloam

With horrid warning gaped wide,

And I awoke and found me here

On the cold hill's side.

12.

And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is wither'd from the lake,

And no birds sing. |

1. Put the following events in the order they appear in the poem:

- ..... The lady sat on a horse and sang.

- ..... The knight woke up and found himself where he is now.

- ..... The knight says he made a garland and bracelets for her with flowers.

- ..... The knight says he met a beautiful maid in the wood.

- ..... The poet describes the knight as looking lonely, tired and sad.

- ..... The lady gathered plants for the knight and said she loved him.

- ..... The poet addresses the knight and asks him what has happened to him.

- ..... The lady took the knight to her cave and cried.

- ..... The knight kissed the lady’s eyes to console her.

- ..... The knight offers what he has said before as an explanation for his situation.

- ..... The knight had a dream about pale kings, princes and warriors who warned that the lady had enslaved him.

- ..... The lady sang to the knight to make him fall asleep.

- ..... The knight’s complexion is described as pale and sickly.

|

This inductive, task-based approach to the texts gave me the opportunity to let the students understand the text at first in general, also thanks to the pre-reading activity, which aimed at creating expectations to the poems and at anticipating some language. The reading activity enabled the students to work on the linguistic comprehension of the poems without translating them into Italian.

MAIN ACTIVITY 2

Once they had understood the poems in general, we went on with a second step, which was a close reading and a detailed text analysis of the two poems on the base of different tasks for a group work.

As far as the first poem is concerned, each group focused on one stanza and analysed its themes, style, and language by doing the exercises I provided to them. Moreover, each group listed on separate sheets of paper all the elements connected with the relationships between BEAUTY/ART/IMAGINATION on the one hand and between TIME/ART/DEATH on the other hand, which are present in the stanza they had to analyse. At the end of this activity each group had analysed one stanza of the poem, which introduced the process of knowledge-sharing to the students, and was put to work later on with presentations.

|

⇛

TEXT ANALYSIS

GROUP 1: STANZA 1

1. The stanza opens with the Poet’s address to the urn as if to a living creature. He in fact calls it

..........bride..............

...............................

...............................

The personification of the urn is emphasized by the adjective ............................................ (l. 1)

What connotation does it have? (Tick)

- intellectual

- sexual

2. The urn is outside Time: to underline this concept, attention is focused on three abstract words:

...............................

...............................

........slow time..........

The urn is so beautiful that, although wrapped in silence, it communicates something better than words and verse. Quote the lines which suggest this concept.

.......................................................................................................

.......................................................................................................

What idea of Art does this description convey?

.....................................................................................................................

3. Lines 5-10 of the first stanza contain the description of one side of the urn. Find the questions or sentences which make up the following scenes:

- the tale is decorated with leaves .....................................................

- and it is about some people, maybe men or gods ..................................................

- the scene is set in certain valleys of Greece ......................................................

- there are some reluctant girls .....................................................

- one of the young men is pursuing one of the girls ......................................................

- but the girl is trying to escape ......................................................

- some people are playing instruments ......................................................

- and the atmosphere is full of joy ......................................................

GROUP 2: STANZA 2

1. Stanza 2 proposes the idea that unheard harmony is sweeter than audible harmony. To underline this concept, the poet has recourse to contrasts:

.................................. unheard (and) ditties of no tone

........sensual ear........

What is the meaning of this opposition?

.........................................................................................................

2. Lines 15-20 constitute the first key point for understanding Keats conception of Art, especially plastic art. The poet says that

the fair youth will.......................................................................................

the trees will............................................................................................

the bold lover (though unable to reach his maiden and kiss her) will.....................

the girl will...........................................................................

What is the meaning of this declaration? What idea of art does it convey?

.................................................................................

GROUP 3: STANZA 3

1. Stanza 3 compares the differences between human physical love and the love anticipated and wished for (though “still to be enjoyed”) on the urn.

Love on the urn is Human love leaves

....................................... .......................................

....................................... .......................................

....................................... .......................................

Which, therefore, is “far above” the other? (Tick)

anticipation of love

consummation of love

2. In what way does Art contribute to the anticipation of pleasure more exquisite and sweet?

..............................................................................................

GROUP 4: STANZA 4

1. Stanza 4 portrays a new, different scene. While the scene on side one is set in a Greek valley, this one is set outside a ......................., located either by a ........................., or by a ........................, or on a ................................ The stanza opens in an idyllic serenity emphasized by the images of the ......................... altar and of the .......................... citadel.

2. But soon the tone changes and the attention is focused on words such as “.............................” (=deserted), “................................” (=mute) and “...........................” (=forlorn).

What image do they suggest? (Tick)

merrymaking sadness

peace joy

GROUP 5: STANZA 5

- In stanza 5 the poet once more returns to the urn as a complete und unified work of art. No longer personified as in stanza 1, it has now become an inanimate object, as is evident from the use of such abstract words as

..............................., ........attitude......... , ....................................

- The poet uses the word “cold” to describe the urn. It may have more than one meaning. Tick the one(s) you consider most convincing, and explain why:

- the urn is made of marble

- it remains indifferent to the anguish of those who try to solve its mystery and the mystery of eternity

- art makes everything immortal, but also static and lifeless.

- Lines 49-50 constitute the second key point of Keats’ conception of beauty. The often quoted statement seems to lend itself to various interpretations. Tick the one(s) you think most convincing and explain why:

- truth is beautiful because it engages our deepest feelings: conversely, beauty is truth.

- it is only through beauty, which is revealed through an intense spiritual experience, that we can come to know truth

- both truth and beauty are immortal

- truth has a permanent and everlasting value; so beauty, which can achieve an equally permanent value in a work of art, can only be compared to truth.

- Thus, what does the urn symbolize? Complete the sentences below with the words suggested:

The urn symbolizes ...................... and ......................, which provide an .................... from ..............,

.............................., and ........................... into .............................

(change – eternity – escape – beauty – decay – art – time) 10

|

The same was done for the second poem, as every group focused on one specific element in analysing the poem:

GROUP 1: BALLAD FORM

- Note down the rhyme scheme and the metre of the poem.

- As in many ballads, the poem is written in a question-answer form. Identify the parts spoken by the poet and those by the knight.

- Find examples of alliteration and repetitions.

- Underline all the archaic words.

GROUP 2: MEDIEVAL ELEMENTS

List all the medieval elements you find regarding:

- form

- subject

- characters involved

- atmosphere

GROUP 3: DREAM

Focus on the dream the knight has in the second part of the poem. What kind of atmosphere does it introduce? Choose from among the following adjectives:

surreal creepy dangerous magic dark

eerie gloomy petrified deathly idyllic claustrophobic serene

Is the atmosphere of the dream different or similar to the atmosphere we find in the first part of the poem? Is it easy to distinguish between dream and reality?

GROUP 4: CHARACTERS

- How are the knight and the lady described? Underline all the expressions referring to each.

- How would you describe their relationship?

- In what way is the courtly love theme treated?

|

At the end of the group work every group presented the results of their work. The rest of the class was supposed to take notes by filling in the grid provided by the teacher:

GROUP 1 : BALLAD FORM

| RHYME SCHEME AND METRE |

|

| QUESTION-ANSWER FORM |

parts spoken by the poet: lines ..............................

parts spoken by the knight: lines..............................

|

| ALLITERATION AND REPETITIONS |

|

| ARCHAIC WORDS |

|

GROUP 2: MEDIEVAL ELEMENTS

| FORM |

|

| SUBJECT |

|

| CHARACTERS INVOLVED |

|

| ATMOSPHERE |

|

GROUP 3: DREAM

| ATMOSPHERE OF THE DREAM |

|

| ATMOSPHERE AT THE BEGINNING |

|

GROUP 4: CHARACTERS

| KNIGHT |

|

| LADY |

|

| RELATIONSHIP |

|

| COURTLY LOVE |

|

This activity was extremely important because it fostered the process of knowledge-sharing among the students and was also good linguistic training since it created a situation with an information gap. In fact, the students who presented their results had to try and be as clear as possible: they had to take into account the quality of their delivery in order to be understood. On the other hand, the students who had to fill in the grids practiced their listening skills and the ability of taking notes during a presentation.

⇛ DISCUSSION AND INTERPRETATION:

After analysing the poems in detail, I stimulated a discussion among the students about possible interpretations of the poem on the following topics, by writing the following bullet points on the board:

- The role of poetry as a means to overcome death and to achieve immortality

- The role of beauty in a work of art as a source of inspiration, consolation, and joy

- The difference between physical beauty (subject to decay) and spiritual beauty (immortal) and how the two are interrelated

- The role of imagination in the perception/creation of beauty

|

The students discussed the points at first in pairs, then in plenary.

As far as the second poem is concerned, the students worked in groups. Every group took one paper strip containing one possible interpretation of the poem and had 10 minutes to think about it and to work out a convincing short speech (1min) in order to persuade the rest of the class of this interpretation.

INTERPRETATION

La Belle Dame Sans Merci symbolizes sensual love, which leaves lovers tired and bewildered.

La Belle Dame Sans Merci symbolizes death, which exercises a morbid fascination on the poet.

La Belle Dame Sans Merci symbolizes the femme fatale, who traps those who love her in a labyrinth of dreams.

La Belle Dame Sans Merci symbolizes poetry and beauty, which here, however, no longer mean consolation, but destruction. |

This activity was important not only because it let the students speculate on possible meanings of the poem, but also because it provided an occasion in which they could practice long turn speeches. One person out of each group gave then a speech trying to convince the class that their interpretation was the correct one. At the end of all the presentations the class started a discussion on the topic. I wrote the linguistic functions the students would have needed to express agreement/disagreement on the board, like: “I absolutely agree with you. In fact I think that...” “I agree with you, but I’m actually not sure that...” “I can see your point, but...” “I’m afraid I really don’t agree with you...”.

Both activities were important for promoting communication within the class and for practicing listening and speaking skills in a context of opinion gap. The students learned to watch things from somebody else’s perspective and to identify with someone else’s point of view by sustaining a thesis which was probably different from their own.

⇛ FOLLOW UP

As a follow-up activity I then proposed, at the end of the lesson, a choral reading of the poems. I played the poem on the CD player once again and asked the students to concentrate on the pronunciation, on the intonation, and on the rhythm. Then I divided the class into groups and asked each group to practice a coral reading of only one stanza each. After the training, taking turns, the groups read their stanzas chorally, so as to give a polyphonic reading of the whole poem. This last step was not only relaxing but also linguistically relevant because, by reading the poem aloud the students could appreciate the sound and the melody and memorize new vocabulary at the same time (like in a choral drill).

In conclusion, the whole experience was in my opinion quite successful for the promotion of both communicative and literary competence. In fact, as I already mentioned, students were not used to an inductive approach to literature. Nevertheless, starting from the texts and from the tasks the teacher gave them, they managed to make their own hypotheses on the main topic of the lesson (Art and Beauty in John Keats’ poetry). They also succeeded at analysing the poems through the guided exercises in a context of cooperative learning and the sharing of opinions. As for the language, they were able to share information and points of view, by using the linguistic material provided by the teacher. In the read-aloud exercise, which was quite difficult at the beginning, the students were able to coordinate and to find the right pace, thus experiencing the sound patterns of a poem in the foreign language.

The ability to communicate effectively in English is regarded by SLA scientific literature as an important goal in ELT (see: Council of Europe, 2001). What students should achieve is the capacity “to operate effectively in the real world [...] to communicate their needs, ideas and opinions [...] to acquire, develop and apply knowledge, to think and solve problems, to respond and give expression to the experience” (Hedge, 2000, p. 46). Such a competence of communication strategies is neglected in Italian education system, every time students are asked to learn linguistic functions and literary content by heart, but are not allowed to reformulate their thoughts in other words when teacher asks.

What I tried to achieve with my teaching units was, with concern to different action contexts, a real communicative practice through the creation of different tasks, based on opinion, reasoning or information gaps. Thus, I tried to give the students the opportunity to concentrate on the meaning and not only on the form and to acquire the language in a more natural way. Moreover, I tried to involve the students in different activities in which they had to give their own contribution to the lesson in terms of reasoning and personal opinion, by fostering and inductive method both with respect to language and to literature. In conclusion, my very aim, by fostering emotional participation of the students, was to create long term learning and to contribute to their holistic education. By providing opportunities for independent thinking, I tried to give the students responsibility for their own learning and to promote abilities, like predicting, justifying and defending their ideas, which they could transfer to other circumstances in life, even outside the class.

1 A special thank to Assunta Nappi for suggesting me the topic of this paragraph.

2 SSIS is a two- year post-graduate school of specialisation that aims to prepare Italian teachers to their future job giving them specialistic competences in didactics and knowledge about the education system. The course is organised as a set of both theoretical and practical workshops focused on the acquisition of the most advanced tecniques for the teaching of a foreign language. During the school year, trainees were also requested to absolve a teaching practice in secondary schools of different kind. During the first year the practice consisted in the guided observation of curricular teachers during the English class, while during the second year trainees themselves were requested to lead the English class by planning and teaching some didactic units about different topics and in different school grades.

3 Città Scuola Pestalozzi is an experimental school based on the pedagogical principles of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, who believed in an holistic approach in education and in the idea of cooperative learning. The school is organised as a mix of psychological and technical education with particular concern about inductive approach to knowledge acquisition (learning by doing) and cooperation (peer-learnig).

4 This teaching unit was inspired by the CLIL- project Losstt-in-Math (Lower Secondary School Teacher Training IN MATHematics) of the Charles Univerity in Prague. With reference to this project, see also: Hofmannovà/ Novotnà.

5 To explain what a lucky number is, I mention here the procedure we gave the pupils to calculate the sequence (see also: Hofmannovà/ Novotnà): “Choose a number. Square each of its digits and add the squares to get a second number. Square the digits of the second number and add the squares to get a third number. Continue this way to get a sequence. If the sequence ends up in 1, the original number is called lucky. If not - it is called unlucky.”

Example: 13 → 1+9= 10 → 1+0= 1 → lucky

17 → 1+49= 50 → 5+1= 6 → 36+0= 36 → 9+36= 45 → 16+25= 41 → 16 +1= 17 → loop: unlucky

6 It was a lesson on Günther Grass’ novel Blechtrommel, more precisely it dealt with a text analyses of the chapter “Kein Wunder”, on the base of elicitative techniques and transfer-activities, in which the pupils had to re-elaborate the main events, the contents and the thematic key points of the text by working with different forms of expression, like: “visualise on a poster the author’s position towards religion”, or “write a diary-entry as if you were the main character describing your feelings”, or “act out a conversation between character A and character B in which the two different positions towards the issue X are underlined”. In a class of native speakers this method was particularly interesting because it fostered a personalised approach to the text and the inclusion of high thinking skills (hypothesizing, inferring, noticing, predicting). Within a language class it can moreover foster the use of the language in a context of authentic communication by creating the conditions of information or opinion sharing.

7 For a more general theoretical framework to an integrated approach to teaching literature in the EFL classroom, see: Savvidou; with reference to this point, see also: Weist, 2004; Brumfit, 1985.

8 To this extent, literary competence can be seen as the ability to understand the textual conventions of a specific textual genre (the literary text). Thus, it can be considered as a particular case of a more general textual competence, which is one of the major aims of the foreign language class. With reference to the role of textual competence in foreign language class, see also: Portmann-Tselikas & Schmölzer-Eibinger, 2002.

9 For a theoretical framework of a task-based approach to literature, see also: Jazbec, 2004.

10 The text-analysis exercises are partly taken from: Marioni Mingazzini/ Salmoiraghi, 1998, p. 93-98.

Please check the CLIL for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|