What Happens When Students Do Creative Writing?

Vishnu S Rai, Nepal

Vishnu S Rai is an associate Professor at the Department of English Education, Tribhuvan University where he teaches ELT and trains teachers. He has written many books on ELT and Linguistics which are taught in local colleges, and published articles in national and international journals. His interests lie in research, creative writing and materials design.

E-mail: raivishnu1@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Objectives

Tools for data collection

Boys group: the products

The products

Analysis

Nature of tasks

Informal talk with the students

Acknowledgement

References

There are fallacies in circulation that literature should not be used in a language classroom particularly in a foreign language classroom, because it is beyond the learners' understanding, because they do not have the language competence to understand and enjoy literature, because the literary language is entirely different from the day-to-day communication and so on. Recent studies show that use of literature, particularly creative writing, immensely helps the learners to develop their foreign language competence. In fact, 'literature is all round us' (Maley 2006) and to keep learners away from literature is to withhold an opportunity that might help them to learn language better and faster.

Creative writing is making a mark in language teaching today. Rejecting the view that creative writing cannot be taught, Bell (2001) shows evidence to the contrary. Similarly, Dornyei (2001) claims that a very good reason for teaching creative writing is that it increases learner's self-confidence and self-esteem, which leads to increase in motivation. As they become more self-confident, so they are prepared to invest more of themselves in these creative writing tasks. In her research, Tan Bee (2007) found that creative writing provides more opportunities to the learners to play and practice with the target language which are both interesting and helpful to them to learn the language. Creative writing not only enhances the writing skills of the learners but it helps learners to enhance all the language skills.

Language learning is facilitated by affective engagement (Arnold 1999) and creative writing tasks foster fun and playfulness. Creative writing provides the learners with new ways to play with the language and as they play more with the language, they learn more. It is said that as learners are engaged to manipulate the language in interesting and demanding ways, attempting to express uniquely personal meanings, so they necessarily engage with the language at a deeper level of processing than with expository texts (Rai 2008). The importance of playfulness in L1 can hardly be exaggerated (Cook 2000). The more a child plays with the language, the more he learns and the more he learns the language, the more confidence he has to play with it. The other important thing about creative writing is that it encourages learners to take risks (Maley and Mukundan 2008) and as a result the learners are able to create novel sentences. However, this playfulness, this encouragement for taking risks which helps creativity is not ‘the absence of constraints, but their imaginative –yet disciplined –development.’(Boden 2001).

In order to see if these claims made by the supporters of creative writing are true, the researcher conducted a mini-research study. The present paper is the report of that experimental research.

The objectives of this study were as follows

- To find out if the students really play with the language while doing creative writing tasks.

- To find out what strategies the students adopt (process of solving the tasks) to complete the creative writing tasks.

- To find out if there are novel concepts expressed in novel structures (products of the tasks).

- To find out students’ views on the usefulness of creative writing.

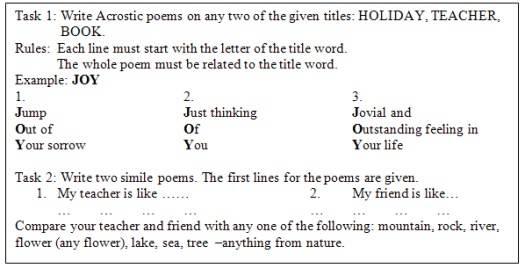

The research was carried out in the Nepalese context. Two tasks were given to the subjects. They had to write two types of poems (a) Acrostics and (b) Simile. They were asked to do the tasks in pairs.

In addition to the tasks, post-writing interviews were conducted with the participants. The participants were the students of M.Ed. with major English. However, they have never been taught creative writing. This was the first time when they did any kind of creative writing.

Two groups of boys and girls participated in this experiment. The researcher explained the tasks and the purpose to the participants of both groups and both groups did the same tasks separately. The members of each group were asked to talk together and discuss while doing the task and their discussions were audio recorded. When they finished their tasks, the products (the poems which they have written) were also collected for analysis. In addition, the researcher talked informally with both the groups to find their opinions and feelings about the tasks.

It is interesting to see the products of the tasks but the process is even more interesting. Because of space limitations, the transcription of all the recordings (data) is not included here. Only two, one for the acrostic and the other for the simile task from each group (boys and girls) are provided here. The transcription of the discussions of the two groups are very similar; the only difference is that girls have also used their native language, Nepali in their discussion for doing the tasks, whereas the boys did not use Nepali –they used English throughout their discussion. This was most probably because they thought that as students of Master level with major English they should not use any other language than English, although the researcher had explicitly told them that they could also discuss the task in their native language. The transcription of the recordings given under the heading 'Process' are 1 from the boys group discussion and 2 from the girls group discussion.

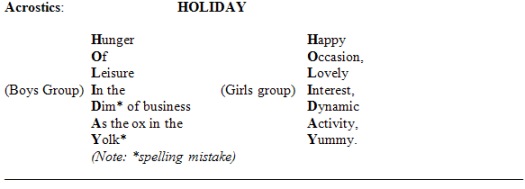

Each group wrote two acrostics and two similes but because of space constraints only one acrostic and one simile from each group are given below.

Similes

1. Our teacher is like a rose (Boys Group)

Smiling amongst the thorns

Teaching the knowledge of struggle and hardship

And spreading the perfume of love from the Pandora’s box.

2. My teacher is like a river (Girls Group)

Which flows forever

Without caring ups and downs

Having a lot of hopes and dreams.

Both the products and the process were taken into account for the analysis. A summary of the comparison between the two tasks (data) is given in the following table.

|

Acrostics |

Simile |

| Products |

-More complex structures

-More novel and surprising ideas

|

-Less complex language

-No surprising ideas

|

| Process |

-Lots of repetition, back and forth,

-More playing with the language

-Thinking aloud in case of Ramesh

|

-Repetitions but less playing with the language

-Less discussion between the pair

|

| Time |

-More time taken: 20 minutes |

-Less time taken 15 minutes |

| Others |

-Acrostics create more opportunities for L2 making and L2 creativity, requiring learners to construct meaning through L2 directly

-Participants found it more challenging as well as interesting |

-Participants found it less challenging

-Excessive L1 use may hinder pportunities for the destabilization of learners’L2. |

If we compare the products of the tasks, it is clear that the acrostic poems have far more complex

language (particularly of the acrostics written by the boys) than that of the simile ones. Not only that but the comparison also shows that the acrostics have more novel and/ or surprising ideas than those of similes. Particularly, the acrostic HOLIDAY (if we overlook the linguistic mistakes “din” spelt as “dim” and “yoke” spelt as “yolk”) has some very novel and surprising ideas expressed in a complex (metaphoric) language which describes holiday as ‘hunger for leisure’ by which the students mean that today man has too much work to do and he always looks for a break from his work –always hungry for leave. Another novel expression in the same poem is ‘ox in the yolk’. By this they mean people are like bullocks tied to the yoke to plough the fields (this is true to Nepalese context because in Nepal most farming is still done with the help of bullocks to plough the fields). The acrostics written by girls do not have such complex structures as they stick to one word per line but the idea is certainly novel. The poem ends with the word 'Yummy' as if holiday is something to taste. It is interesting to see that the boys’ group considers 'holiday' as a time for rest since life is full of work (din of business) and their work is as tiresome as that of a bullock. On the other hand, the girl group considers 'holiday' a 'happy occasion' to enjoy, something 'lovely' and 'interesting', an occasion when they become active (dynamic activity) and something very tasty.

In comparison to acrostics, simile poems are straightforward, in the sense that one can fairly guess what is coming next, e.g. rose presupposes thorns, teaching presupposes knowledge and perfume love. However, even in simile we find expressions such as 'Pandora's box' which refers to the Greek mythology in which Pandora was created by the god Zeus and sent to the earth with a box containing many evils. When she opened the box, the evils came out and infected the earth. But Pandora's box has been used in the poem entirely in a different sense. Probably the idea is that as the evils from the box infected the earth so do the ideas from the teacher's Pandora box sterile students' brain. While the boys group compares their teacher with a rose which blooms among thorns (hardships and suffering), the girls’ group compares their teacher with a river which has to flow though many 'ups and downs' (hardships and suffering). The comparisons are different but the idea behind them is very similar: the same idea has been expressed differently.

If we look at the processes (or the thinking) involved in doing the tasks, acrostics took more time to be completed than the similes. The girls’ group took more time than the boys’ group to finish both tasks. The recordings of the girls’ discussion for writing acrostics (which are not given here) were longer than those for the similes. This also suggests that the participants played more with the language in doing acrostics than in similes and that they ventured to take more risks in inventing and using the language in acrostics which is why they have novel ideas and surprising constructions.

A comparison between the two types of writing also shows that, while doing acrostics, participants did more chaotic thinking whereas in doing similes they were more straightforward. There were a lot of repetitions, going back and forth and checking the ideas, etc. in acrostics. So their thinking and the discussion were not as systematic and organized as in similes, however eventually they ended with as organized writing in acrostics as in similes.

There are different approaches to creativity viz. the product approach which refers to the characteristics of creative products, the process approach which refers to the thinking involved in creative tasks and the linguistic approach which refers to the language play in the task. They all suggest that acrostics are better than similes and it leads to another striking fact that constraints rather than freedom help learners to be more creative. While writing acrostics the students had to follow certain rules (each line must start with the letter of the title, etc.) whereas in writing similes they had to follow fewer rules (e.g. teacher or friend should be compared with any natural object).

A comparison between the products of the two groups shows that the acrostics written by the boys were more complex both in structure and ideas. In the process, girls discussed more than boys, probably because they were three in number and they took more time than the boys to finish the tasks. They had more lively discussion than boys and they played with the language more than their boy classmates. Their discussion also supports the view (Tan Bee 2009) that in writing acrostics conceptual systems (ideas) are activated through L2 directly, then translated into L1 and that acrostics create more opportunities for L2 making and L2 creativity, requiring learners to construct meaning through L2 directly. But while doing similes, concepts are first retrieved in L1 then translated into L2 and that excessive L1 use may hinder opportunities for the destabilization of learners’L2.

Most of the discussions in both groups were carried out in English. The girls discussed partly in Nepali when they did the simile task. Boys said that they because the task was in English, they should do the discussion also in English, although it would have been easier to discuss in Nepali. One boy said that because the task was given by their teacher (the researcher), and as they were students of English, they thought it just proper that they should discuss in English and the others agreed with him. They thought that probably their teacher would not be happy if they did not carry their discussion in English. This was the main reason for them to use English throughout in their discussion but they also said that it was easier to think and discuss in English for the acrostic task.

If we look at the nature of the tasks, we can present it as follows.

Acrostic Simile

Rule-based task Imagination foregrounded

Formal constraint Foregrounds the imaginary situation (imagine A as B)

Semantic constraint Foregrounds discourse (give two reasons)

Acrostic writing offers less freedom than simile writing and yet provides learners with more opportunities to play with the language. Its products are better in terms of novel use of language as well as novel ideas. So, constraints rather than freedom initiate more chaotic and form-oriented thinking and play, and scaffold creativity. This supports what Boden (2004) says, ‘creative thinking is made possible by constraints’. Creativity does not come from absolute freedom: it is guided by internal discipline which the learners or the writer imposes upon them. The experiment shows that acrostics, which put more restraints on the learners create more opportunities for L2 making and L2 creativity than similes, which have more freedom.

An informal talk with both the groups revealed the following facts.

- They had never done these kinds of tasks.

- The tasks were challenging but interesting and they liked them.

- Writing acrostics was more challenging.

- They (boys) discussed in the English language only because this was an English lesson.

- They (girls) also used their first language in their discussion because it gave them more ideas.

- These kinds of activities will certainly be liked by students.

- They are very happy and proud that they can write poems in English: they had never thought that they could write poems in English.

The talk with the students clearly showed that they were very proud that they could write poems in the English language. This sense of achievement which the learners feel after creative writing activities is one of the reasons why creative writing is becoming more popular. Their replies also went in favour of what Krashen (1986) says about 'comprehensible input': if the tasks are challenging but not too difficult or too easy, then the learners are more motivated to do the tasks. Their feeling that creative writing activities are interesting supports the idea of bringing literature into the foreign language classroom.

I am indebted to Dr Tan Bee Tin for the idea for this research, which replicates the research she carried out in Indonesia in 2007.

Arnold, J. (1999) Affect in Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bell, J. and Paul M. (eds) (2001) The Creative Writing Course book. London: Macmillian.

Boden, M. (2001). Dimensions of creativity. Boston: MIT Press.

Cook, G. (2000) Language Play: Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dornyei, Z. (2001) Motivational Strategies in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krashen, S.D. (1986) The Input Hypothesis: issues and implications. London: Longman.

Maley, A. and Mukundan J. (2008) Empowerment in action: Creative writing by Asian teachers for Asian learners.

Maley, A (2006) English Through Literature. Beijing: Central Radio and TV University Press.

Rai, V.S. (2008) Creative Writing: The Latecomer is the Winner. Journal of NELTA Vol. 13, No 1.2.

Raimes, A. (1991) ‘Out of the woods: Emerging traditions in the teaching of writing.’ TESOL Quarterly 25: 407-30.

Tan Bee Tin (2007) What happens when students do creative writing? A research report presented in the Creative Writing International Conference, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|