Editorial

This article is based on a paper of the same title given at the 20th Conference of the Association of Portuguese Teachers of English, entitled 'Twenty Years of Challenges and Decisions' in April 2006.

(Re) Searching Ourselves: TEFL Teachers as Bottom-up Agenda Setters or Top-down Consumers?

Mark Daubney, Portugal

Mark Daubney is an EFL lecturer and teacher trainer at Leiria Polytechnic, Portugal. His interests are interaction, teacher education, affective factors in language learning and teaching, and qualitative research. E -Mail: mdaubney@esel.ipleiria.pt

Menu

Introduction

Setting or following the agenda?

Characteristics of successful teachers and learners

Barriers to overcoming challenges: external barriers

Barriers to overcoming challenges: internal barriers

Searching and researching: the cycle of improving teaching and learning

Implementing the cycle

Personal reflection on the implications of the cycle

Conclusion

References

This paper is aimed at the English language teaching profession/community in Portugal as a whole and not just at teachers of a particular cycle of education. In fact, I feel the theme of this paper is applicable to all teachers of English regardless of the levels and age ranges with which they work, and although the experience and contextual factors upon which this paper is based are uniquely my own, I believe that some of the challenges that I have personally faced and have attempted to understand are experiences that may help others to reflect on and act within their own teaching contexts. I include in my thinking here teachers working in other countries, too.

A few facts about myself and my teaching experience here in Portugal: first of all, I am a native speaker of English; secondly, I have worked with learners of all age groups; thirdly, I have worked both in the state and the private sectors; fourth, I am both a teacher and a teacher-trainer; finally, I have worked in Portugal for approximately 13 years now so I would like to think I am in a reasonable position to make a worthwhile contribution to the debate surrounding the challenges and decisions facing us today.

The central idea of this article can, I hope, be inferred from the title. The bottom line is this – do we always wait for curricula innovation, policies and change to be forced upon us by those exercising power from above or do we as teachers, teacher trainers and teacher-researchers take it upon ourselves to lay down challenges for ourselves and allow ourselves to shape, to a greater degree at least, some of the key decisions and changes that we are faced with or will face in the future? Do we always want, wait and expect to be spoon-fed with the educational know-how and innovative initiatives that trickle down from on high or do we use our own experience, insights, training and daring-do to do some of the initiating ourselves?

Before going on to grapple with some of the challenges/problems that are thrown up by these questions, I would like to briefly state some of the problems that EFL teachers have faced and are likely to continue to face in the classroom: getting pupils to speak English, motivating pupils, indiscipline, inadequate materials and keeping ourselves motivated. Of course this brief list is by no means definitive, but it is, I think, representative of the type of problems that many teachers face today.

Now let me make another list, again by no means exhaustive, but this time of the characteristics of a successful language learner: autonomous, creative, prepared to take risks, hard-working, prepared to seek out new learning experiences, motivated, open-minded, having good language skills, and cooperative. Now, if learning is a lifelong process and we, as teachers, are doing our best to bring out and enhance such qualities in the classroom, then what about the qualities of the teachers themselves? Surely, we have to lead by example, and surely this means it is desirable that we have all of the above characteristics and many more besides. If we do have these qualities, then I would argue that we have a greater chance of minimising the type of problems cited above.

Yet if we are to lead by example, then this, I would argue, necessarily entails a constant (re)evaluation of our own practices, competencies and training. In fact, the starting point of the biggest challenge of them all is, in my opinion, taking a good, hard, long look at ourselves. In other words, we need to ask ourselves some searching questions and, just as important, answer these honestly before turning to many of the external factors pressing in on and shaping our professional lives. What I am suggesting here is that as teachers we should take the initiative and carry out our own projects in our own local contexts. However, I do not want to make this appear a case of simply taking out our DIY teacher-kit, quickly putting it together in the classroom and neatly addressing the challenge without a hiccup. On the contrary, facing and dealing with challenges takes time, resources and dedication.

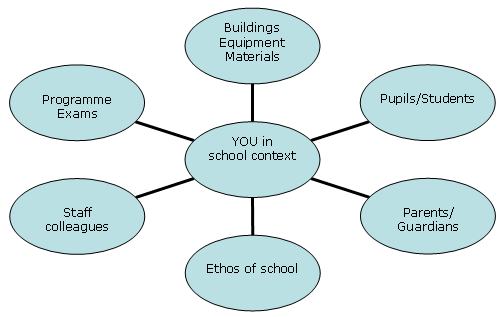

Let me now move from the level of abstract ideas to that of practice on that most difficult of playing fields, that of the classroom, and relate to you some of the tricky opponents I have faced as an English as a foreign language teacher here in Portugal and I how I have tried to tackle them. In fact, what I have tried to do is to elaborate a framework of how to start dealing with the challenges that face us. Basically, in order to face and better deal with challenge, we have to assess the possible barriers to overcoming challenges. The possible barriers may be within us or outside of us. Let us first take a look at what I consider to be the easier barriers to assess; those that exist outside of us. The diagram below illustrates some of the possible barriers related to our school contexts to overcoming the challenges that face us.

Possible barriers to overcoming challenges: looking outwards and searching outside ourselves

In order to implement a more innovative, stimulating and, ultimately, more adequate language learning environment in our classrooms, a classroom more in line with preparing our students for change, employment and encounters with speakers of other languages in a fast-moving world, not to mention facing the challenges being set by an ever-increasing globalisation, then we need to see more stimulating materials, relevant tasks and a much greater slice of the classroom action being reserved for spoken interaction. Yet in my experience as a teacher-trainer and as a teacher in both private and state sectors EFL teaching, in state schools in particular, remains stubbornly traditional and depressingly dependent on a chosen student book that is religiously adhered to throughout the academic year. If we are supposed to be preparing our pupils for a rapidly changing and volatile society, then plodding through lessons from page 1 to 78, in which the teacher talks at, but not necessarily to, the pupils is hardly going to be an adequate let alone stimulating structure for these future citizens.

Materials, and I include in this category student books and their accompanying workbooks, cassettes, CDs and DVDs to name but a few, are not always the most suitable, but teachers can pick and choose. It's not as if we are all in strait-jackets and have no choice whatsoever! Of course, many teachers feel they are limited to a great extent by the programmes published by the education department and parents and/or guardians' demands. First, a programme has objectives, but how the teacher goes about achieving those objectives is not under the control of the Ministry of Education. Teachers must be willing to experiment! Secondly, to paraphrase many a comment from parents and guardians, 'we've bought the book so it should be used'. And so it should but this does not mean that teachers have to use the book in every lesson or do every single exercise in the book! Again, the teacher is the manager or facilitator of learning in the classroom.

Another possible barrier may be the pupils themselves. Their beliefs about what a lesson, and more specifically an English lesson, should be like have firmly taken root by the time they are thirteen or fourteen years old. This is why the implementation of a range of interactive, fun, and largely orally-based activities in English classes by competent teachers in primary school is so important. Many teachers and students still hold the belief (cf. Daubney and Nunes, 2005) that foreign language lessons should have significant portions of explicit grammar study, that the teacher should stand at the front and that conversation in the classroom is somehow just idle chat. Indeed, I have had the experience on more than one occasion of students supposedly losing their concentration once spoken interaction has started whilst suddenly regaining attention once I have begun to write something on the all-important blackboard. This suggests an experience of traditional teacher-centred activities in classrooms where the lay-out also remains traditional. In fact, the inattention or loss of concentration on the part of students in oral-based activities may well be the result of their beliefs being challenged or the fact that they are simply not used to or are even scared of interacting, scared of spontaneity, a fear that has been fed by a dependence on the student book and somewhat wooden interaction often based on display questions. Recently, I was observing a 6th year (twelve and thirteen year olds) English class being taught by a trainee teacher, and also present in the classroom was an Erasmus student from the Czech Republic, also doing a teacher-training course, who was shocked to see that the pupils were sat in traditional rows behind each other and facing the teacher and not in a circle or at small tables where pupils could see each other's faces and hear what their colleagues were saying without having to turn round and stare at the speaker which, for most pupils, simply increases the pressure to say things 'correctly'. Furthermore, reorganising the classroom and implementing 'noisier' activities may often incur the displeasure of colleagues and even go against the school ethos. In today's world, this barrier may prove a tricky one to overcome. School management and the ethos of the school often demand a 'serious' classroom environment, where an (over?) emphasis on tests and exams takes precedence over interactive activities that are often considered as 'light but not serious learning'. Just reorganising the classroom lay out can result in colleagues complaining of having to put the chairs back or there being too much noise transmitted to the classroom next door. Whilst acknowledging such attitudes are often difficult to overcome, there are ways to minimise confrontation and generate greater understanding for your classroom practice. Five minutes at the beginning and end of the class can be put aside to change the classroom lay out, and pupils can be encouraged to do this quietly and efficiently. Explaining to your colleagues the reasons for pupils facing one another, for example, may help them to understand your decision. In the same school where I observed the class in which the Erasmus student was present, another trainee-teacher decided to teach her form about Pancake Day, but this lesson also included a demonstration of how to cook pancakes and pupils also had the chance to eat some, all of which was done in another classroom and which had to be organised and agreed upon within the school. All well and good, but when one parent heard about this lesson, she complained to the school that her child was meant to be learning English not learning how to be a 'baker'! In fact, this trainee was essentially teaching English in this lesson using the CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) approach, one of the most innovative approaches being promoted by and in the European Union at the present moment in time. Taking risks and doing things differently will often involve uncomfortable moments yet this should not deter us from experimenting in our own contexts; what we should be ready for, however, is to justify our choices and practice.

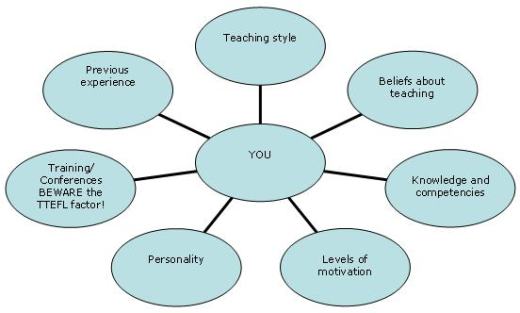

Let me now move from 'looking outwards', that is to say looking at some of the external barriers, to looking inwards, the internal barriers that are, in my opinion, more difficult to identify and assess, precisely because it is difficult to create a distance and look critically at oneself and one's practice. The majority of human beings have a tendency to attribute 'failure' and 'difficulties' to things outside themselves, so we not only need to take a critical look at ourselves but also embrace honesty and responsibility as essential factors in this looking-inwards process. The diagram below illustrates some of the possible barriers located principally within us to overcoming the challenges that face us.

Possible barriers to overcoming challenges: looking inwards and searching ourselves

Before looking at some of these factors in more detail, it is necessary to point out that the external and internal factors are by no means mutually exclusive but are in fact reciprocal and dynamic influences on each other, for example, one's beliefs about teaching and language learning will determine to a significant extent, even though we may not be aware of these beliefs, the type of activities we implement and materials we use in the classroom. To give a concrete example, if you believe, as I do, that spoken interaction is the cornerstone of learning and, hence, speaking the most important language skill, then many of our activities will be based around speaking activities. Likewise the perceptions of our own competencies will influence our own interaction, for example, if a teacher feels more secure when explaining grammar as opposed to interacting more spontaneously because of a lack of confidence in their speaking skills, then more routine, traditional grammar exercises may well be the staple diet of that teacher's practice. To give one last example, a teacher's teaching style may well clash with the learning style of many of their pupils, what Oxford (1999) refers to as 'style wars'. A more extrovert teacher who expects visible participation from their students may well face considerable resistance from more introvert pupils who prefer a more reserved approach to learning whereas a teacher who favours close reading of texts and closely controlled exercises with an emphasis on grammatical explanations may well frustrate those wanting greater discussion, debates and fewer exercises dedicated to the explicit study of grammar.

Despite this dynamic influence on each other, the internal factors are closely related to our perceptions, our personality types and beliefs, and in many respects potentially more controllable as opposed to the external factors which, despite being easier to identify, are generally speaking, further from our direct control. In other words, if we want to exercise greater influence over those external factors in out own teaching contexts and begin to set our own agendas in the classroom so as to improve classroom life and the learning that takes place there, then we first need to look inwards, at ourselves as language teaching professionals.

I have already spoken, although very briefly, about teacher beliefs, teaching styles and competencies and the way these may be barriers to more effective learning and teaching. In facing challenges by taking the initiative, there are also other potential barriers. Our own levels of motivation are extremely important. In today's world teachers face constant change and challenge and the education system in Portugal, like many other countries, is undergoing radical changes at the present time. Life in the classroom is tough for many teachers so motivation is often the life force that keeps teachers going, and pupils notice and feel this. Pupils know which teachers are going through the motions and which are bringing in different and stimulating activities, which teachers know their names and which do not, which teachers genuinely talk to them and which ones talk at them. Without sound levels of motivation, the idea of setting our own agendas and improving our teaching will not go far. Our personalities will also have a significant influence on our practice. This influence may well be positive but it is quite possible that our personalities may be a barrier to our overcoming challenges. Influencing our teaching styles, levels of motivation and beliefs about teaching and learning, teachers' personalities may unduly influence their practice. For example, a shy teacher may not favour more spontaneous interaction with their pupils because of the public exposure it subjects them to whereas a sociable, outgoing teacher may have a tendency to claim centre-stage and deny many students the opportunity to speak. Teachers' previous experience – both as learners and teachers – will also shape what they do in the classroom and may also prove to be another barrier to overcoming some of the challenges that face us. What is successful in one classroom will not necessarily be successful in another, what is seen as a failed activity in one class may go really well in another. In fact, previous experience works on many levels – the schools in which we have studied as pupils and worked as teachers, the activities that we thought successful and enjoyed and those we didn't, and the way pupils have reacted to us personally are just a few of the many factors that make up our previous experience.

If we accept that all of these factors influence teachers as professionals, their teaching and teaching contexts, then it should be no surprise that I said that facing challenges takes time and dedication, a complex process that requires honest reflection, and this point brings me to the final internal factor, which is our perceptions of and experiences in training sessions and conferences – what I call the T-TEFL factor or the Trivialisation of teaching English as a foreign language.

Let me first make this very clear – conferences and training courses are extremely positive, stimulating and motivating events, well worth our time and providing us with important opportunities of meeting other professionals and getting to know other practices, in a nutshell, essential for our professional development. But on the other hand, the language used and the sessions given often give the impression that teaching is a piece of cake, that activities and approaches are quickly and easily implemented and learning is a 'product' that is duly delivered at the end of the class. Let us not forget that conference sessions are filled with willing and motivated participants on the look out for new ideas and who, generally speaking, give the speaker a ride he or she would not likely find in the majority of classrooms. Indeed, catchy conference and session titles ('The course book that leads your pupils to autonomy', 'How to make grammar easy', 'Making motivation easy', 'Getting your pupils to speak in 3 easy steps') often reflect this simplistic perception of teaching and dovetails conveniently with many teachers' (false) desires to find easy, practical activities, along the lines of ten-minute class-fillers. Of course, such fillers are valid, but teaching and learning require responses to complex situations, and this complexity should be acknowledged. If speakers want to scare off teachers from their workshop, talk or plenary session, then just drop words like 'reflection', 'research', and theory' into the title! What effect does this T-TEFL factor have? It may well lead to teachers feeling somewhat dispirited at the gap between what happens in their own classrooms and those of the conferences because of this simplification of the difficulties our profession faces both in and outside of the classroom.

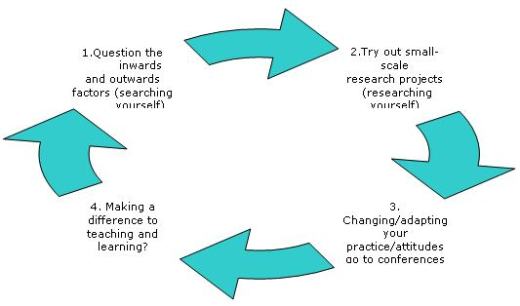

So barriers to our facing and overcoming challenges may be evident in both the external and internal factors that I have mentioned. Searching ourselves, then, and questioning both sets of these factors is a first step. However, searching is not the same as researching, and this is the next, essential, step to teachers becoming agenda setters in their own classrooms. Many competent teachers may already be searching, trying out different activities in the classroom, thinking about whether they work and then adapting and trying them again. However, researching is more systematic and essentially involves having a question or questions to answer, collecting data to answer that question, analysing that data and coming to conclusions based on that data. However, mention the very word 'research' to teachers and other professionals and this conjures up images of white coats, serious-looking scientists and unfathomable statistics, in short it represents something beyond them and of which they are suspicious. The diagram on the next page shows a cycle of how to put your own research projects into practice in the classroom.

Facing the challenge: improving teaching and learning

I would now like to give a practical example of how such a cycle can be put into practice. The students I was working with when I carried out a research project were future second cycle teachers of English on a pre-service training course at the School of Education at Leiria Polytechnic in Portugal, and I was their teacher. My main research question was the following: if these students are training to be English teachers, then why don't they visibly participate more in the classroom? Visibly, because the fact that students do not speak in the classroom does not mean they are not participating. In fact, many students actively participate in lessons without actually saying anything! I collected my data by video-recording some of their lessons, asking them to answer questionnaires, interviewing them and also asking them to fill in comment sheets after each lesson.

What did I find? The factors that seemed to significantly influence their participation in classes were their perceptions of the following factors:

- their futures as teachers

- the role of the teacher

- the classroom methodology used

- their oral skills

- student-teacher interaction

- their own personality

- their language learning experience

Here are some examples of the above factors – in their own words - from three of the four students that were the subjects of my research project:

Sónia:

- Perceptions of oral skills: "Tinha medo de cometer erros linguísticos e de me esquecer" (I was scared of making language errors and forgetting)

- Perceptions of student-teacher interaction: "Preocupo-me muito mais quando o professor se centra apenas na minha exposição oral" (I worry a lot more when the teacher is only focusing on what I say)

- Perceptions of their own personality: "Praticar uma língua é sempre importante e útil para todos aqueles que anseiam dominá-la por completo." (speaking a foreign language is always important and useful for those who are anxious to master the language)

Renata:

- Perceptions in relation to future as teacher "…tenho sempre muito receio em relação ao meu futuro como professora de Inglês." (I've always been scared about my future as na English teacher)

- Perceptions of role of teacher "eu simplesmente nem tinha iniciativa eu já ia para a aula já não tinha aquela aquele vontade de participar eu tinha medo" ( I simply wasn't motivated, I was on the way to lessons and didn't feel like participating, I was scared) [student was scared of her then English teacher]

- Perceptions of oral skills "…continuo a estar preocupada com a minha oralidade." (I'm still worried about my speaking skills)

Susana:

- Perceptions of classroom and classroom methodology "… a nossa maior queixa (em relação às aulas de Inglês) prendia-se com a ausência de diálogo em Inglês o que contribuiu para a insegurança" (our biggest complaint is that there has been an absence of dialogue in the classroom which has contributed to our feelings of insecurity)

- Perceptions of oral skills "Antes de falar tenho a necessidade de pensar em Português, o que por vezes atrapalha." (Before speaking, I have to think in Portuguese and that sometimes trips me up)

- Perceptions of role of teacher "it's more motivating if the teacher is warmer with us"

I would now like to move on to the implications for MY classroom AT THAT TIME based on my THEN research with THOSE students. I strongly highlight these words as it is important to stress that our own particular contexts are unique. Although we are right to use other peoples' research findings to shape, inform and carry out our own initiatives, findings from other projects cannot simply be generalised from one class to another.

The role of the teacher was seen to be important: students felt the teacher should be able to grab the attention, be a motivator, be open and warm, interested in their students and a facilitator of learning. Closely connected to the role of the teacher were the perceptions of student-teacher interaction: the teacher should appreciate students' contributions and not simply concentrate on grammatical accuracy and the teacher should give students time to think and formulate answers. It is worth mentioning here one of the features of my own interaction with students that I only noticed after studying the video recordings of classes and which may help to clarify the difference between searching and researching. In the recordings I noticed that I often gave students a chance to contribute on their own terms. If I noticed a sign of willingness to communicate on the part of a student (for example, a smile in my direction, a facial expression that suggested they were going to say something) but they didn't end up contributing, then I would go back to that student as soon as I could and ask, "Sorry, Joana, were you going to say something?". Although this is what is known as a direct solicit, it had a face-saving option built in and was not face-threatening. In other words, they could contribute if they felt like it but if they did not, this could build up their confidence to make a contribution later on as they probably guessed they could make a contribution when they felt like it as opposed to being 'forced' to make one. This seemed to result in more contributions from certain students who were reluctant to speak at times, but I was not conscious of this strategy until I had studied the recordings as part of my research. It was only through systematic study that I was able to notice this. Many competent teachers, I am sure, search for ways to better understand their teaching contexts but research involves a more systematic process involving the steps I mentioned earlier.

Students' comments also pointed to time as being an important factor – for them to think, prepare and produce the language. This not only seems particularly important for certain activities like role-plays and debates which frequently lack the necessary vocabulary, structures and mental preparation and as a consequence often die an early death (Daubney, 2006), but also for what teachers may often feel are routine questions. Getting a response as accurate as possible in front of colleagues and teacher in a formal environment where the sense of evaluation – social and academic – heightens the fear of making mistakes (in terms of vocabulary, pronunciation and structures) is not as routine as is so often believed. Materials, activities and themes were also cited as being of importance. Sometimes students do not participate because they simply have nothing to say on a certain subject, so this only goes to show the importance of getting to know our students' interests in order to adapt our classes to students' needs. Silence as a student-response to our questions may not be the result – as is often assumed – of reluctance to speak or of uninterested students, but in fact the result of a 'poor' question, one that is not clearly expressed or inadequate in terms of level of language. In fact asking questions, giving instructions and clarifying doubts in the target language remain difficult speaking skills to master and often teachers will quickly resort to Portuguese – or other languages! – justifying this code-switch because the pupils 'do not understand English' when the real culprit may often be the teacher's lack of linguistic competence, a classic case of blaming the external factors as opposed to looking more closely at the internal ones. Classroom organisation was referred to in the sense that students thought that pair and group work are useful before having whole-class discussions or making individual presentations, therefore providing the opportunity of a dress-rehearsal and allowing students to get in to the spirit of the activity.

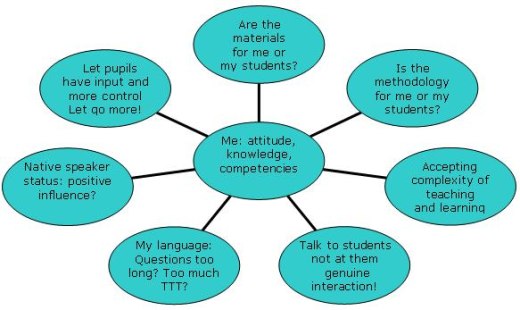

Taking these findings from my research into account, I have changed and adapted my practice but above all my attitude and approach to teaching. By being involved in research projects, reflecting on what I do and adjusting my practice accordingly, I feel I have progressed as a teacher precisely because I do reflect and act. I am now in a better position to face change, which in itself often involves challenge, to research and therefore to better understand my own classroom and to implement the changes I deem necessary, that is to say, to be an agenda setter in my own classroom. In the diagram below are some of the key notions related to my own practice to which I have given particular attention.

A personal reflection on my own practice: key factors

As I have already spoken about some of these points, I will briefly refer to just a few of these key factors. First, as a native speaker I believe this status generally has a positive affect on students – they feel that I am a genuine source of contact with English culture and language and therefore this is a motivating dynamic. Yet sometimes there may be potential for negative influence on students, for example, students may see their discourse as somehow 'not good enough' in comparison with mine and therefore be reluctant to speak; at other times I feel that my innate knowledge of the language and lack of formal language learning experience has dulled my sensitivity to students' needs. It's always good to put ourselves in the shoes of our students! A related point is that I have also been guilty of choosing materials – articles, videos, reading comprehensions and grammar work – which perhaps I chose with my own interests in mind as opposed to my students'. Indeed, the methodology I have implemented in class may well have suited my teaching style more than the styles of my students. In fact, talking explicitly to the students about what they like and dislike in classes is a challenge in itself – something they may initially be suspicious of, and resulting in them giving us the 'expected' responses – but a challenge worth persevering with because it not only gives us direct feedback on our lessons but also allows us to build a more open relationship with students, giving them more say in the classroom, and a way of talking about their lessons and language learning experience through the target language. This is what I refer to in the diagram above as 'letting go'. The last point I will refer to, and one which I have already mentioned, is talking to, not at, students. For some teachers, this comes easy, for others it is a most difficult process. For others, it is something that 'gets in the way' of the lesson plan and carrying out the programme. As a supervising teacher, I have often noted that the most dynamic part of the lesson is the warm up, the short question and answer sessions or brainstorming activities at the beginning of class. Motivation and enthusiasm are often high, arms go up and students are ready with their answers and, very often, further, voluntary, contributions. Yet somehow opportunities for further interaction are missed, the momentum lost, and the teacher guides the class back to the lesson's activities not always because of a lack of willingness to interact but probably, in my opinion, because they are scared to 'let go'. This may be because they are unsure of their oral skills, they feel as if they are not 'teaching' or not keeping to the lesson plan and therefore not carrying out the programme, in the final analysis not doing their job. Whatever the reason, one of the challenges I have faced and would ask other teachers to face, too, is to allow for spontaneous moments in the language class, to part company with the lesson plan if it appears such a digression will be fruitful. Sometimes, the most interesting classes I have given – or should I say been involved in? – have been those that have not always followed what had been planned.

Concluding I would like to say that many good, conscientious language teachers may search themselves and their local contexts but not necessarily carry out research. Seliger and Long (1983: vii-viii) assert that:

"Good language teachers have always acted like researchers, realizing that language teaching and learning are very complex activities which require constant questioning and the analysis of problematic situations…Important questions can lead the language teacher to shrug them off or step back, observe dispassionately, form hypotheses about what has taken place, and then carry out his or her own research in the class."

I would argue that there are a significant number of language teachers in Portugal and elsewhere who do not even consider important questions let alone carry out their own research. However, I do believe there are also a significant number of language teachers who do get to the point of attempting to do something about the problematic situations these questions may pose, searching as opposed to researching, so the challenge I would lay down to language teachers of all levels of education is to carry out their own research initiatives and become better teachers instead of waiting for the initiatives to be passed down. Nobody knows a teacher's classroom better than a good teacher does. In the words of Michael Wallace (1996), who was writing ten years ago about the challenges facing language teachers in a fast and ever-changing world:

"The teachers who will thrive in this new environment are those who are capable of generating their own professional dynamic, who are pro-active rather than reactive."

Ten years on and with changes coming thick and fast, I would argue that one of the biggest challenges we need to face is to transform the language teaching profession from a reactive one into a pro-active one, a profession that because of its dynamism and local initiatives increases quality from the bottom-up as opposed to a profession that, all too often, waits to be fed from the top-down.

Daubney, M. and M. C. Nunes (2005) When is a lesson a lesson? The APPI Journal, Year 5, no. 2 Autumn Issue, 4-9.

Daubney, M. (2006) Keeping up appearances: motivating and maintaining pupils' interest in role-plays. The APPI Journal, Year 6, no. 2, Autumn 2006, 13-18.

Oxford, R. (1999) Style Wars as a Source of Anxiety in Language Classrooms. In D. J. Young (ed.) Affect in Foreign Language and Second Language Learning: A Practical Guide to Creating a Low-Anxiety Classroom Atmosphere. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 216-237.

Seliger, H. W. and M. H. Long (eds.) (1983) Classroom-orientated Research in Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Wallace, M. (1996), Structured Reflection: The Role of the Professional Project in Training ESL Teachers. In Freeman, D. and Richards, J.C. (eds.) Teacher Learning in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.281-293.

Please check the Skills of Teacher Training course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Expert Teacher course at Pilgrims website.

|