The Forgotten Learner: Why Language Teaching Has to Be Humanised

Marko Maglić, Germany

After finishing his studies in English/Spanish, Marko Maglic spent a decade in IT-business. He then started his teacher traineeship in 2004, now teaching at two schools in Cologne, Germany. Current interests comprise e-learning, teaching life-skills at school, and the quality of learning. He is running several websites on language learning and teaching. Homepage: www.maglic.de E-mail: marko@maglic.de

Menu

"New Learning" in the 21st century

Learning: Group vs. Individuals?

Individual needs and the group

Conflicts as a basic human need

Learning, emotion, mood, and the teacher

Motivation – what can the teacher do?

Summary / Conclusion

References

That the turn of a century has always been an indicator for stronger changes, can be observed in relation to recent renewals in learning and teaching: In the "decade of the brain" (1990s) neuroscientists gave us new insights on how our brain functions (Kandel), and the concept that we create our own reality subjectively has finally found its pedagogical echo in constructivism. The analysis of communication and social systems done by Luhmann, Habermas, Watzlawick and other distinguished scientists led to new pedagogical developments again: Learning is now being regarded as a social process, learning has to be social, and it has to include the learning of social skills economy needs.

Cooperative learning in groups, through games, student-activating methods and student-centred education are the pedagogical keywords of the beginning 21st century: Training principles such as Gardner's multiple intelligences, accelerated learning or NLP – already put into practice long time ago in business orientated trainings – have meanwhile been partially established at school. Norm Green's model of cooperative learning and Klipperts method are central for teaching in Germany.

With the "New Learning" arising, the curricula standardization – serving governmental and economical needs – takes care about the topics and contents our students have to learn. The PISA experiences Germany made led to a boom of centralized evaluations ("Lernstandserhebungen"): We must know what our students learn, and how effectively they learn the compulsory contents. That these, combined with the new forms of learning, are "highly motivating" is taken for granted. As a result, teachers' bookshelves have been flooded with new material promising successful teaching. Today, methodology seems to be the key to motivating our students.

Though it is evident that students are working more enthusiastically when experiencing these new methods, one essential question remains unanswered within this context: What about the individual?

Of course, modern constructivist and socio-psychological theory regards the student as an individual and the theory of multiple intelligences opened our eyes for the individual approaches to experiencing the world. But we still have to ask: Where and when are the very personal needs of the individual paid attention to?

Role-plays, for example, are considered to be highly motivating. They are so definitely – for a majority. But what with students who definitely refuse to take part in such activities? Should we give them bad marks for non-participation? Or even worse: Should we force them to participate and at the same time make them feel bad, knowing that negative emotions have a negative impact on learning?

What about the contents prescribed through the national curricula? The topic of migration, obligatory in Germany, illustrates that the subjects might not be that motivating: When entering Secondary II, students have already dealt with migration in several courses: German, Sociology, History, Geography, and English as a foreign language. The English curriculum of the recently centralized A-level exams in North-Rhine-Westphalia (Zentralabitur NRW) now provides "Migration in the USA", as well as the "Situation of immigrants in the UK". In case students chose Spanish – a language now very popular among students which they start to learn enthusiastically – they will have to talk about migration from Mexico to the USA, and migration from Africa to Spain/Europe again. Can you imagine the students' faces at the moment they are communicated their topics? (Not to mention that after having studied Spanish for three years, they might be able to write an essay about migration, but in fact are not able to communicate on a small talk level with a native speaker?)

What about the students with stronger needs for exercises? At least in Germany, the new forms of learning are student-centred, what in fact means that they are group centred. Understanding takes place in groups, and so do the communicative activities. The problem here is that a real understanding by all the group's individuals is not always given, and that some students need – what they call "real" – exercises before engaging themselves in communicative activities. (Hauck & Hurd, 2005, analyze learners' language anxiety in a detailed way.) Should we neglect our students' needs here, pretending to know what is better for their language learning? Or should we deny that through hundreds of years language learning always had a strong focus on (drill) exercises? Is there reliable empirical evidence that the "new" learning is better than the "old" one?

Is it necessarily better to have students studying a text with their partner or in a group, when they still are not able to communicate on the meta-level required for such activities? And should we then oblige them to use the target language for such a difficult cognitive work, what might lead to frustration instead of the desired mutual stimulation?

Given that such questions have not yet been answered in a convincing way; the teacher is in a difficult position:

The dilemma a modern language teacher faces today is that on one hand a modernization of learning is always desirable, and that the governmental standardization programmes have to be followed when – on the other hand – learning groups have to be motivated for learning. The group's motivation depends on the individual student's motivation, but the balance between the group and the individual is difficult to find and often leads to a partial neglect of the letter. Despite this, only when taking the individual fully into consideration teaching can be student-centred, or better: Human.

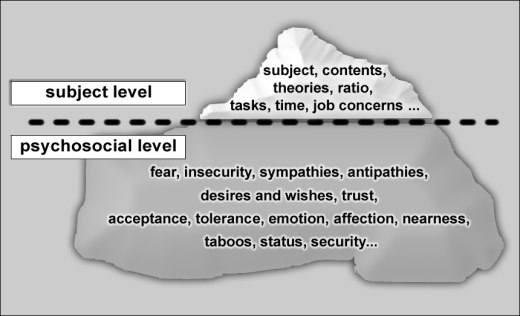

In order to find the right balance a solid understanding of how groups function is indispensable; they are complex social systems in which the subject level can only be the tip of the iceberg:

Maglic: Groups – An Iceberg (Based on Gugel, 2006, p. 33)

The formal educational issues remain on the subject level and are mostly shared by the group of learners, whereas the intra- and interpersonal concerns are to be found at the underlying psychosocial level. These – regretfully and in spite of their unavoidable omnipresence – are often neglected.

Only when living the emotions and needs related with this level a group can function, and an individual can function within the group. Neglecting them can only lead to a kind of Titanic-experience. The well-being of the individual and the group is thus a crucial prerequisite for the learning process. According to Zajonc, teaching the "living together" has to be a central task for the teacher:

The curricula offered by our institutions of higher education have largely neglected this central, if profoundly difficult task of learning to love, which is also the task of learning to live in true peace and harmony with others and with nature. (Zajonc, 2006, p. 1)

For our learners, the functioning of the group and their own functioning within the same is vital, as this meets several of their needs: Especially children and adolescents need the feeling of being loved and "belonging to somebody". In relation to the iceberg-model, this need is to be found under the tip, i.e. it is not that visible for us.

At the same time our learners need a certain level of self-esteem: Acceptance, tolerance and mutual respect aren't given by nature, they have to be experienced and learnt within the psychosocial processes every group undergoes.

Fear and insecurity have to be overcome by nearness, trust and a feeling of security.

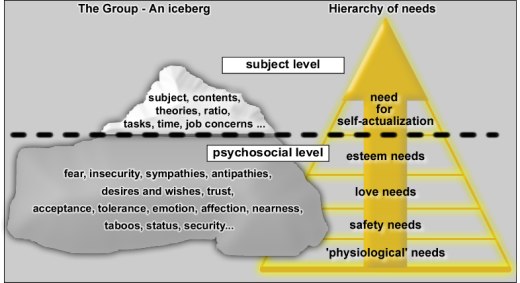

Theoretically we of course know that positive emotions have a positive influence on the learning process itself. But still we see teachers complaining when students need a glass of water during class, or - for whatever reasons - their chewing gum to be chewed. Such 'physiological' needs form the base of Maslow's hierarchy of needs:

Maglic: Maslow – Hierarchy of Needs (based on Maslow, 1943 and Wikipedia, 11.07.2007)

For Maslow (1943, p. 370), the appearance of one need usually rests on the prior satisfaction of another, more pre-potent need, what he illustrates with the example of food:

For the man who is extremely and dangerously hungry, no other interests exist but food. He dreams food, he remembers food, he thinks about food, he emotes only about food, he perceives only food and he wants only food. (ibid., p. 374)

Maslow didn't insist on that one need has to be satiated 100% for being able to address the higher needs; but the basic urge for this need will have to be met to a certain extend.

A graphic combination of the iceberg-model and the needs-pyramid illustrates how the two concepts interweave, and which importance for the individual's learning process they have:

Maglic: Pyramid of Needs and the Group as an Iceberg.

Both models have in common that the subject of self-actualization, in our case the learning process, is to be found at the very top of all other related concepts. As long as the potential conflicts on the psychosocial level are not resolved – respectively the "lower" needs not satiated – a satisfying learning process is being impeded, if not made impossible. Thirst could thus impede learning, and a chewing gum could make the learner think only about having it.

If - according to actual academic trends we understand the teacher as a coach, as a learning facilitator; their job is not only to care for the tip of the iceberg (to teach at the subject level), but to manage and coach all implicit psychosocial processes that facilitate learning.

A real learning process on the students' side can only take place if teachers are able to establish a psychologically and sociologically positive environment. This doesn't only include admitting what we commonly regard as "positive" emotions, but includes alleged "negative" as well, as the case of group conflicts depicts:

A wide range of sociological studies focuses on managing group processes and conflicts, understanding conflicts as chances. At school, instead of an open conflict management, a tendency to avoid conflicts can be observed: Conflicts seem to have a negative touch and are disturbing or disruptive factors.

Decisive aspects of conflicts for group and learning processes are thus ignored: They contribute to the homogeneity of groups, and preserve the existing when at the same time they guarantee changes. Persons involved in a conflict have not only to reflect about its obvious cause (subject level), but to reconsider their position and views (psychosocial level) deeply. The meaningfulness (Sinn) of conflicts lies in the development of complexity concludes Schlötter (2006, p. 88), summarizing the work of (Schwarz, 1990). Hence, conflicts can be considered as complex social systems themselves.

Two major reasons for establishing a healthy and human culture of conflict in the classroom can be pointed out: First of all, conflicts cannot be avoided at all. Secondly, apart from its cause on the subject level, the intra- and interpersonal aspects on the psychosocial level make conflicts a basic need of human beings. Giving way to emotional release, conflicts thus offer an excellent opportunity to e.g. channel aggression and prevent uncontrolled aggressive release at other occasions.

Once the group has gone through its inevitable psychosocial processes, the basic needs of the individual student might at least partially be fulfilled, and the door for a higher level – the self-actualization through learning – is open.

In case the development of the group fails or tends to be a negative one, emotions like frustration, fear and anxiety will dominate the learning environment:

High-anxiety learning environments are known to produce emotive conditions, such as feeling anxious or overwhelmed, that can be counterproductive to the learning process.

(Wallace & Truelove, 2006, p. 22)

It is thus the teachers' task to accompany the groups' processes carefully, and to establish an emotionally stable and positive learning environment for the students. They must be omnipresent and fully emotionally awake, and at the same time somehow absent in order to allow the emotions that lead to a learning facilitating atmosphere:

Good mood promotes the active transformation of new information by applying existing semantic knowledge to incoming information in order to achieve a coherent memory structure (assimilation). Bad mood, in contrast, supports non-elaborative encoding like rote rehearsal without the active application of semantic knowledge to the incoming information. Accordingly, in bad mood the new information is changed very little during encoding so that episodic memory structure has to be altered to fit the new information (accommodation). As a result, participants in a good mood are more likely to employ deep semantic encoding strategies (Craik & Lockhart, 1972) in comparison to participants in a bad mood.

(Kiefer, Schuch, Schenck & Fiedler, 2007, p. 371)

Fear and anxiety have to be avoided, and in case students do not like or even fear their teacher, the encoding process - if it takes place at all –will have a low quality, as Goethe already observed time ago: In all things we learn only from those we love. (Eckermann & Bergemann, 1981: The original text («Überhaupt», fuhr Goethe fort, «lernt man nur von dem, den man liebt».) is commonly referred to as Man lernt nur von dem, den man liebt.)

Relating the concept of motivation with the so far discussed, we can state that the psychosocial level represents the students' basic needs, moods and emotions. Consequently, the motifs to be found on this level are those which dominate students' behaviour: They need to feel emotional security, self-esteem and mutual respect the same way they need to drink or "wash their hands". (According to my observations mostly bodily-kinaesthetic learners, forced to sit a long time without moving, "need" to wash their hands in order to escape this static physical situation that makes them feel uncomfortable.)

Once these needs have been satiated, students can (!) direct themselves towards learning. The point is, they don't always do it due to lack of what we call motivation. Though being researched on more than abundantly, we till today do not dispose of "the explanation" of what it is at all. Mostly – as Hollyforde & Whiddett (2005, p. 3) conclude – it appears that most researchers consider motivation to represent the drive behind human behaviour.

Motivation is not fully recognizable for us, as it originates in the individual itself. Accordingly; People cannot be motivated to do something if there is nothing in it for them. (ibid.) In other words, people only take action if this action is somehow beneficial for them; be it that they will experience positive consequences (to pass an exam), or that they will be able to avoid negative ones (to fail an exam).

Distinguishing between intrinsic motivation that comes from within the individual and extrinsic motivation that comes from outside, we have to take into consideration that any kind of "reward" might provoke negative feelings on the learners' site. Furthermore, given the multiple tasks of a teacher today, it often is impossible for the teacher to establish a kind of systematic reward-system as done within the field of stimulus theories.

External factors attributed to non-motivating learning conditions, e.g. "boring" subjects, negative learner attitudes or deficient facilities and equipment, might decrease motivation. The constant obligatory testing has negative impact on motivation as well: Though at first sight it might serve to motivate, fear and anxiety go always along with it.

Extrinsic motivation, as well as intrinsic if "produced" by external pressure, have limitations and cannot lead to what we expect our learners to do: To learn through inner motivation their whole life long. Even if Motivation is personal and not created by another (Hollyforde & Whiddett, 2005, p. 2), it's the teachers' job to motivate their learners. What teachers, organisations and managers can do is provide the environment, support and resources that will influence and effect motivation. (ibid.)

This might be achieved by adhering to principles established and confirmed by sociological as well as psychological/pedagogical studies:

- The willingness to learn can only be enhanced if the basic needs of the learner are satiated.

- Instead of extrinsic motivation accompanied by reward systems, intrinsic motivation of the learner is to be preferred and focused on.

- The very essential prerequisite for learning is a human learning environment characterized by emotional security and stability the teacher has to establish. Methodology and social learning are thus meaningless unless the psychosocial culture of the learning group has not been positively stabilized.

- The teacher is always a central role model to which learners not only relate to, but from which they as well take inspiration and motivation for learning: Underlying teacher's classroom behaviours will be a powerful set of beliefs and attitudes. (Rinvolucri, 2003, p. 16)

- Authenticity - often related to material - is crucial for the living and learning together: Neither should the processes be artificial, nor the teacher.

- A teacher is not "teaching learners"; he is coaching and helping individual personalities while they learn.

From the observations made it follows that neither for teachers nor for learners the up-to-the-minute methods do necessarily make sense. They cannot replace the satiation of the intrapersonal and interpersonal needs that go along with learning; they can only be supportive means.

The strong focus on constructivist theory, methodology and methods during recent past seems - at least partially - to have forgotten one essential element of the learning process: The learner themself. Only through appreciating the personalities they work with, teachers can accomplish one of their main tasks: To make the students learn continuously as long as he lives.

The key to success can be only one: Motivation. The motivation for such life-long learning cannot be "produced" by the teacher, but as a role model they can animate students to follow their example. A teacher - following the modern theories - has to be a coach, a facilitator, a companion, who enables the student to reach the goals in the best possible way. Compulsory curricula and testing do not really help; neither can the methods offer the solution for this dilemma.

Given the context of such a "prescribed" learning, the ability to arise curiosity on the individuals' site is decisive, as You can teach a student a lesson for a day; but if you can teach him to learn by creating curiosity, he will continue the learning process as long as he lives. (Bedford)

Curiosity, then, can only evolve if the learning environment meets the individual needs of the learner and those of the group.

Inevitably, a "student"-centred approach cannot be sufficient; it has to be "person"-centred and above all: The learning environment has to be human in the sense that it is characterized by mutual respect and continuous striving for meeting each other's needs. Only through fully understanding and appreciating our learners as individual personalities educators will be able to concede them their right to a motivating and inspiring education, preparing them for life-long learning.

Bedford, C. P. On curiosity and learning. Retrieved Jul 20, 2007, from quoteworld.org/quotes/1117

Eckermann, J. Peter, & Bergemann, F. (1981). Gespräche mit Goethe in den letzten Jahren seines Lebens. Insel-Taschenbuch, 500. Frankfurt am Main: Insel-Verl.

Gugel, G. (2006). Methoden-Manual "Neues Lernen": Tausend Vorschläge für die Schulpraxis (Neu ausgestattete Sonderausg.). Pädagogik. Weinheim: Beltz.

Hauck, M., & Hurd, S. (2005). Exploring the link between language anxiety and learner self-management in open language learning. EURODL, (II). Retrieved Jun 26, 2007, from www.eurodl.org/materials/contrib/2005/Mirjam_Hauck.htm

Hollyforde, S., & Whiddett, S. (2005). The Motivation Handbook: Developing Practice. Mumbai: Jaico Publishing House.

Kiefer, M., Schuch, S., Schenck, W., & Fiedler, K. (2007). Emotion and memory: Event-related potential indices predictive for subsequent successful memory depend on the emotional mood state. Advances in Cognitive Psychology, 3(3), 363–373. Retrieved Jul 18, 2007, from www.ac-psych.org/index.php?id=2&rok=2007&issue=3#article_31

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Retrieved Jul 17, 2007, from psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm

Rinvolucri, M. (2003). Humanising your coursebook (Reprinted). Professional perspectives. Addlestone: Delta Publ.

Schlötter, P. (2006). Das Spiel ohne Ball im Unternehmen: Kommunikation sichtbar machen und verbessern. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

Schwarz, G. (1990). Konfliktmanagement: Sechs Grundmodelle der Konfliktlösung. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Wallace, B. A., & Truelove, J. E. (2006). Monitoring Student Cognitive-Affective Processing Through Reflection to Promote Learning in High-Anxiety Contexts. JCAL, 3(1), 22–27

Wikipedia. (11.07.2007). Maslow's hierarchy of needs -- Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved Jul 15, 2007, from en.wikipedia.org

Zajonc, A. (2006). Cognitive-Affective Connections in Teaching and Learning: The Relationship Between Love and Knowledge. JCAL, 3(1), 1–9.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Expert Teacher course at Pilgrims website.

|