Chunks-based Language Learning – Theory and Practice For the Classroom

Manjula Duraiswamy, India

Manjula Duraiswamy has been a Teacher, Teacher trainer and Senior Editor with two different publishing houses. She is an Examiner for the University of Cambridge, Local Examinations Syndicate and is a Language Trainer for corporate clients. She enjoys travel, writing and music and is deeply interested in language development across a variety of contexts. She completed her Doctoral studies on “The Role of Chunks in Second Language Acquisition”. E-mail: manjula92001@yahoo.co.in

Menu

Introduction

Chunks in the classroom

Students and their experience with chunks

Bibliography

Chunks are expressions of varying length combining form and function in an idiomatically controlled context. They are multi-word fragments that can be used in communication to convey meaning that is understood readily by both sides.Each expression has a particular discourse function, and over time people begin to use these expressions ritualistically, as a convention, unconsciously absorbing the intricacies of grammar. Some examples of these fragments include: ‘See you later,’ ‘in the meanwhile’, ‘once upon a time’, ‘in another day and age’, ‘as a beginning’. These form/function composites provide guidelines for effective teaching and learning, coming closest to first language acquisition scenarios. They combine linguistic competence and pragmatic competence leading to effective communication.

Several theories abound but it is generally accepted that linguistic competence is responsible for generating grammatically correct output while pragmatic competence leads to awareness of relevance, implicature or discourse structure. Linguistic competence covers syntax and performance and pragmatic competence covers semantics and syntax. In addition, in both these scenarios we have competence balanced against performance, with linguistic ability filling the gap. In order to explore the full significance of language it is necessary to consider both these aspects combining to form a whole.

According to Becker, (1975: 72) from the perspective of his work in artificial intelligence and spoken language, the frequency of lexical phrases in performed speech implies:

that the process of speaking is compositional: We start with the information we wish to express or evoke, and we haul out of our phrasal lexicon some patterns that can provide the major elements of this expression. Then the problem is to stitch these phrases together into something roughly grammatical, to fill in the blanks with the particulars of the case at hand, to modify the phrases if need be, and if all else fails, to generate phrases from scratch to smooth over the transactions and fill in any remaining conceptual holes. (Becker, 1975: 72)

That is, in speech acts speakers work with a basic template with blanks for particular functions which are filled in with inputs from a phrase store to create grammatical output according to context. Taking this idea forward, it is the ability to use chunks that characterizes fluency as these phrases aid retrieval of lexis and permit users of language to pay attention to discourse as a whole rather than limiting attention to individual words. Some examples of prefabricated language items that have traditionally been recognized as fluency markers are idioms, clichés and non-canonical phrases. While idioms and clichés are easily recognizable as typical ‘English’ inputs, non-canonical phrases like ‘waste not want not’ and ‘off with his head’ do not follow English structures. For example: In the first phrase, ‘and’ and the conditional marker ‘if’ are missing

Learners learn language through invention, experimentation and stories: the language they use is related to imaginative stimuli as words are made to play. In the classroom, there is a wide gap between theory and practice. Students often lose interest in using language if they have to devote too much time and effort to the mechanical aspects of grammatical manipulation. The content becomes subordinate to the mechanics of the language, discouraging and demotivating students and hampering communication.

Course books in the classroom include both representational and referential material as referential language informs and representational language involves and aids meaningful recall. Rather than seeking consciously to promote affective learning, chunks bring about personal interaction between the learner and the text, irrespective of whether they are referential or representational. Chunks methodology makes use of learner capacities for self-awareness, leading them to a wider knowledge of language and greater fluency in it.

Chunks provide a holistic experience that creates and offers opportunities for learning which nevertheless depend on individual learner profile for ultimate success.For example, expressions like ‘sparing no effort’, ‘with a little luck’, ‘taking everything in his stride’ and ‘with a little encouragement’ gradually become part of the active vocabulary of

Meaning-focused activity in class becomes the starting point for internalization of language as learner memories store the cultural and conceptual implications for further consideration and recycling. For example, the learning experience becomes valuable when the teacher uses emotional hooks in the text to recall learning: ‘Do you remember the text we read about playing in the rain?’ When a student recalls and recycles a text, language learning moves beyond the merely mechanical aspect of language. The assimilation or accommodation of new expressions depends on the context in which interpretation takes place.

With chunks, the learning process extends well beyond the moment of interaction with the text, where comprehension is a stimulus rather than an end in itself. The manner in which learner consciousness deals with the text after the initial understanding, becomes an entry point to language learning processes. When lexis is encountered as part of a larger setting embedded in meaning networks which stimulate active engagement with language, both communicative functions and grammar knowledge are enhanced. Once understanding of these items of language is achieved learners are empowered to use them in different contexts.

The layered nature of prefabricated chunks allows a recognizable relationship between form, function and meaning. The context based teaching of stock expressions is a practical way in which chunks methodology can be used effectively in the classroom. The danger in this methodology is that life situations often do not correspond directly with these simulated contexts and the responses practiced remain unused. However the teaching of chunks in context provides the learner with language choices to fit a variety of situations.

The learning of chunks as a way into language accommodates these important stages of learning: Noticing, Understanding and Reflection.

Noticing: Games, role-play and activities

Understanding: Meanings of words and expressions, comprehension and decoding.

Active Reflection: Use in speech and writing

Chunks open doors to language facility providing direction and support wherever required. Learners reflect and explore strategies that are employed to negotiate the text; ambiguity of meaning is enjoyed but it is advisable to change classroom strategies at regular intervals to keep boredom at bay. Focus on chunks encourages depth in understanding, leading to an enriching reading experience which develops free expression and individual critical and responsive capacities. Apart from idioms there are three kinds of chunks that learners would encounter:

- Syntactic strings or items created according to grammatical rules.

- Collocations or frequently occurring word combinations with no pragmatic function.

- Lexical phases (canonical and non-canonical) that combine form and function.

Chunks combine linguistic competence and pragmatic competence leading to effective communication. Language in use is based on form/function composites, which, while being part of grammatical competence, also display specific functions in context, investing them with pragmatic relevance. In reality they appear to have closer links with grammar than appropriate conditions.

The way in which these word-webs mesh to produce language output describes the role of chunks in language acquisition where the boundary between `new' utterances and ‘ready- made expressions’ (example, metaphors) is often blurred. The creative and innovative use of language is intrinsic to human ability enabling extension and the creation of vocabulary. Novel language use finds examples in metaphors while creative extensions find examples in the use of parts of longer expressions. This is seen in ‘Do you have wheels?’ or ‘I’d like to do a Sachin Tendulkar.’

Language production is determined by storage and retrieval of lexical items and if storage occurs as sentence fragments and chunks of information rather than as single items, it is easier to remember and recall relevant language. Short term memory comprises a large number of these units which store lexis in meaningful contexts. This kind of ‘chunking’ facilitates storage. Memorized sequences are the building blocks of fluent discourse, providing models for the creation of new expressions which are memorable and in their turn internally, the stock of familiar usage.

However, memory is more than a balance between perception and production, the organisation of strings of words or chunks, easily recognisable and quickly accessible for production, form an important aspect of this balance.

Along with generative grammar, 'memorized sentences' and 'lexicalized sentence stems' are critical features of linguistic knowledge. The possession of a large stock of memorised sentences and phrases simplifies language production, freeing the learner from the task of composing sequences word by word. The learner can channel his energies towards timing and rhythm and attempt to produce a slightly novel, unexpected variation on usage.

When chunks are used, the juggling of syntactic, semantic and phonological information that is involved in language production is simplified and made ‘user-friendly’: The example of the ‘phrase book’ technique used by tourists learning what is necessary for a short trip to another country provides insight into the way chunks could enhance language acquisition. Two questions arise from this discussion:

- How effective are these collections of phrases in actual interaction?

- What part do chunks play in the comprehension and acquisition of new language?

In the answers to these questions lies the importance of chunks methodology.

Meaning is not a finished product but a continuous and continuing process, where students are involved in translation, and negotiating meanings across cultures. Chunks offer meaning potential, showing that learning is a continuation, not a completion and carry forward the quest for expression. During paraphrase and reformulation useful elements from a piece of text are used to restate the original. Apart from this, reformulation and paraphrase are further facilitated by the embedded grammar rules governing chunks which are, in addition, easily transferred to different situations.

Reformulation and paraphrase contain within them notions of appropriacy and acceptability. As an instance, a sentence like, ‘A doll, a bat, a ball and a spoon played, cried and danced’ is grammatically correct but hardly possible. Reformulation depends on knowledge and use and the ability to interpret, differentiate and select. The capabilities of language users therefore include knowledge of changing language needs in a variety of contents. The brain is able to reapply and interpret items of language with remarkable facility. In short, a subconscious store of lexical data has enormous scope to expand with practice and opportunity. The process of storage and retrieval can be understood better if we study the way in which words are stored and the manner in which retrieval takes place.

In a learner centered classroom, where we believe that our students learn better when they participate actively in the learning process, opportunity should be provided for their active participation in the formulation of the rules underlying the language forms. Grammar is acquired through a process of natural growth and limited periods of conscious learning.

In order to optimize opportunity for the acquisition of grammar, the teacher should:

- provide a wide range of inputs related to learner experiences

- direct learner attention to content with the help of games and activities ensuring that emphasis is on language

Language is a pattern, a kaleidoscope of designs that emerges from a human context to express specific needs. These needs can be related to seeking information, giving instructions or describing a situation, all based on a basic human desire to fit in pieces in a recognizable pattern. If language is based on patterning then all languages should follow an underlying map which allows permissible combinations. This universal map or universal grammar (based on Chomsky’s theory about Universal Grammar) forms a strong unifying strand that e encourages language acquisition. Chunks indicate a relationship between the different aspects of syntax, so that a given option can only be selected if another option in a different part of the network is also chosen. Semantic networks embedded in chunks link behaviour options and grammatical options.

The examples above illustrate the relationship between the various options within an expression. A significant feature of this relationship is the role of depending options. Chunks offer patterns of meaning differentiated progressively by levels of interaction where the meaning potential is realized in the grammatical system.

In this context, the instrumentality of grammar appears to be stressed rather than its autonomy. According to Lynne Cameron, learners develop sensitiveness to patterns and trends in language with exposure to discourse and vocabulary. This understanding is an important stage in the development of learner language knowledge and forms the base for pedagogic grammars and metalanguage.

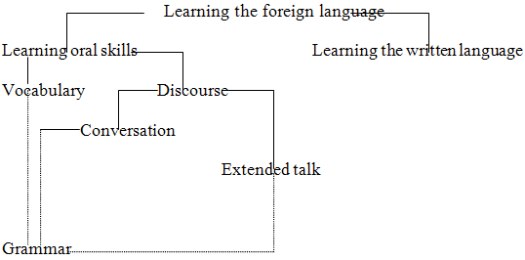

…oral skills can best be thought of as ‘discourse’ and vocabulary’, with both of these being constructs centered on use and meaning, to reflect children’s learning. Discourse is language in use, and often, but not always, occurs in stretches longer than the sentence. The ability to understand, recall, and produce songs rhymes, chants, and stories, found in most YL courses, are all examples of discourse skills. In contrast to these extended stretches of talk, conversational skills involve understanding and using phrases and sentences in interaction with other children and with adults. Vocabulary skills involve the understanding and productive use not just of single words, but of phrases and ‘chunks’ of language.

Cameron, Lynne Challenges for ELT from the expansion in teaching children. ELT Journal edited by Gail Ellis and Keith Morrow 2003-2004: 13.

Formal grammars with their centre in syntax will need to incorporate generative semantics to make them useful in speech and writing. According to Fillmore (cited in Nattinger and De Carrico 1992) “What do they need to know when they use it? It is not grammaticality or acceptability in the non-acceptable uses, but rather contextual acceptability”.

Chunks and their implications for generative grammar provide explanations under language parameters enabling the learner to organize and relate scattered and isolated knowledge.

Aitchison, J. Words in the Mind: An introduction to the Mental Lexicon. Blackwell P, 1987. Print.

---. Linguistics: An Introduction. Hodder Headline P, 1990. Print.

Brumfit, C., J Moon and R Tongue (eds.) Teaching English to Children from Practice to Principle. London: Nelson P, 1991. Print.

Cameron L. Teaching Languages to Young Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University P, 2001. Print.

Ellis, R. The role of input in language acquisition: some implications for second language teaching. 1981. Print. Applied Linguistics.

---. Understanding Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University P, 1985. Print.

Hakuta, K. and Alvarez, L. Enriching our views of bilingualism and bilingual education. 1992. Print. Educational Research.

Prabhu, N.S. Second Language pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University P, 1987. Print.

Wong-Filmore, L. When does teacher-talk work as input? Rowley Mass: Newbury House P,

Wray, A. Formulaic language and the Lexicon. CUP, 2002. Print.

|