A Case Study of Current Team Teaching Perspectives

Michael Okamoto, Japan

Michael Okamoto is a full time lecturer at Shimane University in Japan. He is interested in bilingual education and materials development for the EFL classroom. E-mail: mmanuszak@emich.edu

Menu

Introduction

Defining team teaching and teacher roles

Method and procedure

Results and discussion

Limitations

Implications / Conclusions

References

Despite having no pedagogical support to confirm its effectiveness when it began (Wada, 1994), team teaching has become one of the most important issues in English language pedagogy in Japan (Tajino&Tajino, 2000). Team teaching, which is the joint instruction of two or more teachers in a classroom, most often includes a licensed educator with a proven knowledge of English, the Japanese teacher of English (JTE) being supported by a native speaker of English, the assistant language teacher (ALT) who often lacks any formal training or experience in teaching. Despite its recent upsurge of followers, there remain many unresolved issues in the team teaching classroom.

In their article, “Perspectives on Team Teaching by Students and Teachers” Tajino and Walker (1998) argue that the major continuing issues in team teaching arise from a difference in the perception of teacher roles for both the Japanese teacher of English (JTE) and the assistant language teacher (ALT). Tajino and Walker frame their findings by first defining the concept of team teaching, its purpose, and the continuing issues that inhibit its effectiveness. They then describe the results of a quantitative study that examined student perspectives and expectations of their JTE and ALT counterparts and then compared those results with the teachers’ understanding of the student perspectives and expectations. Although this article was published 13 years ago, the issues are still very relevant to the present team teaching classroom. Problems of communication, lack of adequate preparation time, and differences in the perception and expectation of teacher roles are still the main causes of confusion and frustration in the JTE/ALT relationship. Having felt similarly to the qualitative and anecdotal evidence provided in the article, I decided to replicate the survey used by Tajino and Walker in hopes of discovering present differences in student and teacher expectations at a public high school in Japan, and if by discovering any differences, identify any factors that affect successful language learning. This paper will first identify the roles of both the Japanese English teacher (JTE) and the assistant language teacher (ALT) and identify common issues associated with team teaching. This paper will then investigate students’ expectation of teacher roles in the classroom, and general student opinion of English, and compare those results with teachers’, both JTE and ALT, expectations and opinions. Finally the paper will end with a comparison of the current student/teacher perspectives and attempt to identify any apparent differences.

Team teaching in a Japanese classroom has been defined as “a concerted endeavor made jointly by the JTE and the ALT in an English language classroom in which students, the JTE, and the ALT are engaged in communicative activities” (Brumby and Wada, 1990). This definition, though a bit dated, provides very good insight to the present situation that exists in the Japanese English language class. The ALT and the JTE work together in a communicative setting to encourage language learning and, normally verbal, production. Each teacher contributes to the classroom by instructing in ways that emphasis their individual strengths, which often compensate for the weaknesses possessed by their teaching counterpart. Through the JTE, students are provided with a Japanese speaker who has a strong background in education, who can deliver explanations of English grammar through appropriate meta-language in the student’s native language. However, most often the JTE possesses a handicap of terms of overall English language competence. The ALT on the other hand, although often lacking any teaching experience or background in education, provides students with a live cultural model through which students can identify and attach importance to the learning of English as well as produce native sounds and dialog in the target language (Barratt and Kontra, 2000). Team teaching is employed in many schools, primary and secondary throughout Japan. The largest contributor to the team teaching scheme in Japan by far is the JET Programme which was first established in 1987, and has employed over 50,000 people since its inception (JET Programme, 2011). Nevertheless, there are reoccurring issues that affect the ALT/JTE relationship as well as the effectiveness that team teaching can provide in the classroom. One underlying issue is teacher role in the classroom. In the team teaching method, teacher role is often undefined, which can and does lead to confusion for both the teachers as well as the students. Traditional roles would dictate that the ALT would assist mainly in speaking and listening capacities, and that the JTE would assist mainly in reading and writing settings and activities. However these roles are often blurred due to a number of factors such as: responsibility assigned to the ALT, preparation time, and lack of clear defined responsibilities for each party. According to Kumabe (1996), because of a lack of knowledge/training on how to use an ALT in the classroom, ALTs are often reduced to “tape recorders”, being allowed to speak only when repeating set conversations and vocabulary lists. Furthermore, JTEs on the other hand are described as “interpreters” because the ALT often does not have an adequate foreign language ability to speak the country’s native language.

In order for the team teaching method to function, Tajino and Tajino (2000) state that ALTs and JTEs in Japan should have their own distinctive roles in the classroom but also that often these roles are not defined properly. If properly executed, team teaching would be a more effective method for language acquisition than it is currently providing. Research from Buckley (2000) and Savignon (1983) supports this idea and shows that team teaching is more effective to traditional or individual teaching methods. (i.e. having multiple teachers in a single classroom will provide more individual support for students, multiple teaching styles promote a more dynamic classroom and provide a more effect way of teaching the L2 culture)

After reading the original Tajino and Walker (1998) survey, I too found that it would be interesting to delve into the perception of teacher roles and classroom opinion and identify any misconceptions held between teacher and student. Rather than name “cultural differences” as the main culprit of these misconceptions, this study attempts to understand what the current perceptions toward team teaching are by both the teacher and student. With this, investigations into whether the teachers, both JTE and ALT, understand correctly these perceptions that students have concerning the functions of the JTE/ALT in the classroom. It will also investigate and compare the opinions from 13 years ago with those of present day.

Basing the research questions from the original Tajino and Walker (1998) survey, three research questions have been proposed that form this report. The research questions are as follows:

- For students, what is the overall opinion of their team taught English class, and do their teachers fully understand them?

- What skills do students most expect the JTE and the ALT to demonstrate in class, and do their teachers understand them?

- How do the present expectations and opinions compare with the results of the survey performed 13 years ago?

In order to create an equal comparison to the participating high school that Tajino and Walker surveyed, a high level public high school had to be located. This high school would have to allow a similar number of students that are majoring in English as well as other fields to participate. Also, in order to again create a similar situation to that of the original survey, the cooperation of a school that employed a larger than usual number of English teachers would have to be obtained. Fortunately, such a school was located.

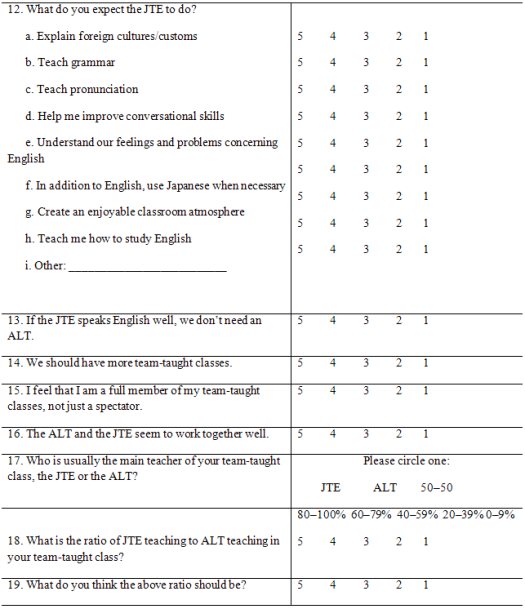

The data was acquired by using a questionnaire (see appendix B) consisting of 21 questions that were translated into Japanese and handed out to 104 students ranging in age 15 to 17. One class from each grade year was selected to fill out the survey. The students that completed the survey were all studying at a public high school in Shiga prefecture. At the surveyed high school, students have the option of majoring in a variety of fields, including English. The selected first year class consisted of a variety of students representing all the available majors. The 2nd and 3rd year classes that were selected consisted of students majoring in English. The high school employs one full time ALT through the JET Programme, who was in their third year of employment at this school. The ALT works at this school throughout the week and assists in teaching almost all of the available English classes. Along with the one ALT, there were seven full time English teachers working at this school that were willing to participate. Teachers were asked to reply based on how they expected their students would answer. The students were given as much time as necessary to fill out the survey. As noted in their article, Tajino and Walker formulated their survey based on previous findings or suggestions stated in other investigations of this kind (e.g. Manto, 1988; Shimaoka and Yahiro, 1990). Although I feel that some of questions were redundant and/or not did directly relate to the original research questions, in order to maintain similar conditions, the exact same survey was distributed to the students and teachers as was distributed byTajino and Walker.

Students were not asked or allowed to write their names or any identifying information. Unlike the Tajino and Walker article, the results from the survey are based on t-test, ANOVA, and frequency of replies and not on Spearman’s Rank-order correlation method due to the fact that there were not an adequate number of participants to ensure accurate results.

RQ1. “For students, what is the overall opinion of their team taught English class, and do their teachers fully understand them?”

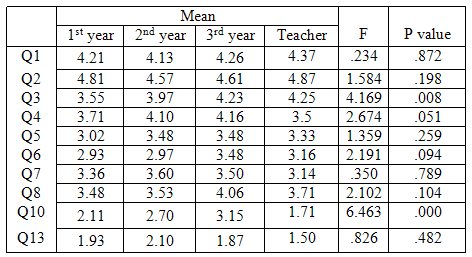

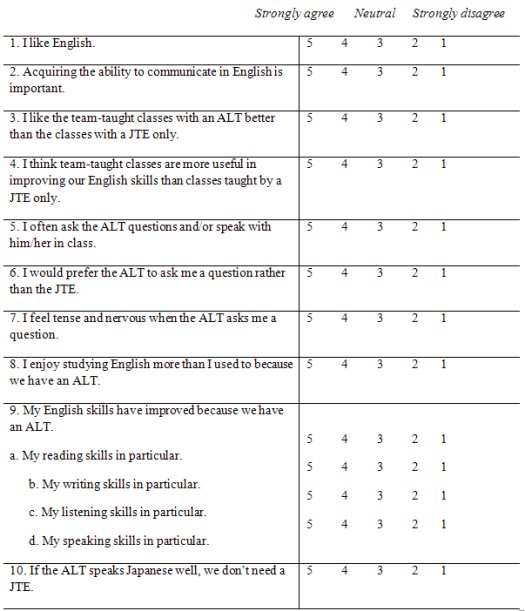

In order to answer the first research question, teacher and student responses from questions 1-10, and 13 were analyzed based on mean and One-Way ANOVA results (see Table 1). The resulted mean for questions 1 and 2, with >4.0 mean for all grades, shows the students’ attitude toward English to be very positive. This question should be very encouraging to all the English teachers at the surveyed school, showing an overall interest toward English. Questions 3 and 4, which addressed student attitude of team teaching over that of individual teaching with response of a >3.7 mean for all replies, reveals that the students desire the currently employed team teaching method over a traditional individual teaching method. Questions 5-8, which concerned the students’ opinion of the ALT, also seemed to be positive with the lowest total mean of all three years being 3.11, revealing no great aversion to the current ALT. Questions 10 and 13 are relational questions comparing the students’ opinion on whether or not the JTE/ALT would be necessary if the other ALT/JTE spoke English/Japanese well. While both 1st and 2nd year students showed a desire for both teachers, the response from the 3rd year students concerning Q10, revealed an opinion showing that the JTEmay not be required (One-Way ANOVA results show a significant difference between 3rd year student responses and 1st year student responses at a < 0.05 level).

Although most of the teacher responses were similar, One-Way ANOVA results show that when comparing 3rd year responses with teachers’ expectations, there was a significant difference at the < 0.05 level from the responses for Q10. This may show that the teachers’ expectations of 3rd year student opinion concerning this question are not correct. Also, One-Way ANOVA results revealed that for Q3, “I like the team-taught classes with an ALT better than the classes with the JTE only.” is lower than what teachers expected. This result may imply that students have a more favorable attitude toward their JTEs than what their JTEs may be expecting. Overall, the response from students concerning their team-taught class proved to be positive. Additionally, it can also be seen that teachers’ expectations of student opinion are also correct.

Table 1 Addressed questions concerning RQ1

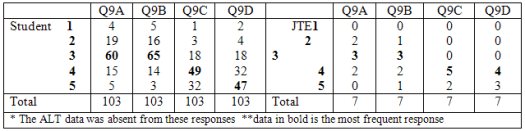

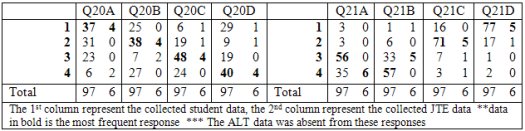

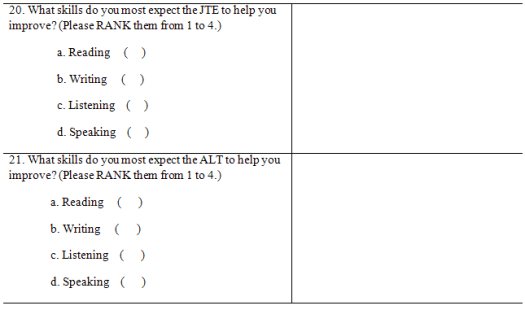

In regards to Q9A-Q9D, despite the fact that the total number of responses for students and teachers varies greatly, it can be seen that the values with the highest frequency of responses for both the students and teachers are very similar (see Table 2). Both students and teachers reported that the JTE has helped improve the students’ skills in order of: writing, reading, listening, and speaking. Because of this, it can be said that the teachers and students share very similar expectations in regards to the current method of teaching the primary language skills.

Table 2 Frequency of responses for Q9A-Q9D

RQ2. “What skills do student most expect the JTE and the ALT to do in class, and do their teachers understand them?”

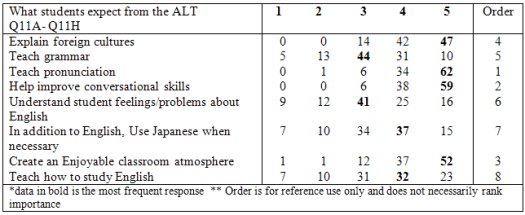

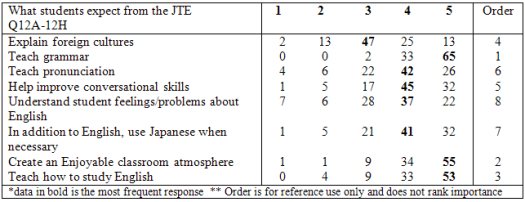

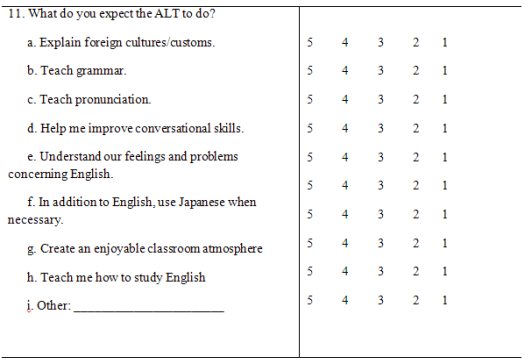

As indicated in Table 3, students most expected the ALT to assist them with pronunciation and conversation skills. This result matches with the ALT’s strongest teaching assets, that of speaking and listening. For the JTE, the students expect assistance with grammar and the creation of an enjoyable atmosphere. Interestingly, as can be seen by comparing tables 3 and 4, students expect the JTE to create an enjoyable classroom atmosphere. Perhaps this is because they find their JTEs to be fulfilling the more enjoyable/interesting role of the two teachers in the classroom. The second result of grammar education expectation is to be expected. Of the two teachers, it is the JTEs that are the most familiar with English grammar, who unlike most ALTs, have at least some understanding of the methods and meta-language required to teach students in their native language. Students may also recognize the JTE as superior in areas of reading and writing comprehension because of their native language ability and experience of having once been a student themselves. Peter Medgyes (1994) addresses this idea by stating that “(JTEs) are generally better placed to anticipate language difficulties; and are likely to have better familiarity with local syllabuses and examinations.” This instrumental motivation of passing language test and examinations is perhaps the most popular reason students study the language and therefore refer to the JTE for the instruction of grammar.

According to the data, students least expect the ALT teach the students how to study, but rather expect this from the JTE. But with this, students least expect the JTE to sympathize with them about their feelings/problems regarding English. This distinction is probably due to the current structure of student/teacher roles in the classroom. Based on this provided data, it can be assumed that students do expect the JTE to teach how to study but do not expect assistance from them in regards to any questions. But rather students must answer any questions they may have on their own or request assistance from outside the classroom. This is an interesting point and the cause of this should be looked into further. Lastly, the data from Q11F and Q12F reveals that students do expect neither the JTE nor the ALT to use Japanese in the classroom. The reasoning for this, having witnessed this personally, can be assumed that this is due to both teachers regularly using English in the classroom and using minimal Japanese while teaching.

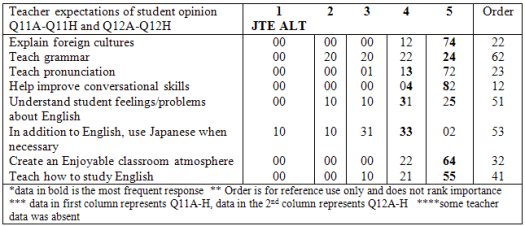

When comparing the student responses with the data collected from the JTEs and ALT (Table 5), the responses show significant differences. These differences could be likely due to the small number of teacher responses when compared to the much larger number received from students. What is clear is that teachers’ expectations of student opinion concerning the ALT are generally correct. Teachers’ expectations concerning the ALT and their role in helping to improve the students’ conversation skills and pronunciation was also correct. This shows a clear shared understanding for both the teachers and students concerning the ALT’s role in this particular school. The teachers’ expectations concerning the JTE on the other hand, are largely different from the student responses. The teachers’ response clearly shows a high expectation concerning Q12E, “Understand (student) feelings and problems concerning English”. As can be seen in Tables 3 and 4, actual student opinion proved to be dramatically different. This may show that the students do not view the roles of the JTE/ALT in the entirely same manner as the teachers presume.

From Table 6, student opinion concerning improvement of the primary language skills is clearly decided. With the exception of Q20A and Q20B in which the responses are slightly mixed, the overall student response toward teacher roles in regards of primary language skill improvement is clear. In order of frequency of response, students expect the JTE to teach: reading, writing, listening, and then speaking. Again in order of frequency of response, students expect the ALT to teach: speaking, listening, reading and then writing. With this data, it can be understood that student opinion of teacher role for the JTE and ALT is clearly determined by the individual strengths possessed by each teacher. For the ALT, there is a preference toward aural-orals skills, and for the JTE, reading and writing. As seen in the previous tables, the JTEs’ expectations of their students are accurate (see Table 6). With the exception of Q21A and Q21B, which may show a slight misunderstanding in regards of reading and writing instruction for the JTE, the responses from the JTE are very similar to the responses collected from their students.

Table 6 Frequency of student and teacher responses for Q20A-Q21D

RQ3. “How do the present expectations and opinions compare with that of the survey performed 13 years ago?”

During the past thirteen years, the Japanese Department of Education often referred to as the MEXT (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sorts, Science and Technology) has introduced many initiatives that have focused primarily on the promotion and improvement of English education nationally as well as internationally. The largest and most active of these initiatives referred to as a “Strategic Plan to Cultivate Japanese with English Abilities” was formulated in July 2001 (MEXT, 2003). This policy plan stated that it will,

“Promote research and development initiatives at high schools across Japan that will contribute to future improvements, and set a goal of sending 10,000 students abroad every year. Second, require all English teachers to acquire TOEFL score of at least 550. Lastly, promote the employment of ALTs attributing to them the possibility of attaining full time status.”

With Tajino and Walker’s survey having been conducted a few years prior to this initiative, I felt it would be interesting to investigate as to whether in policy changes would have any effect on current classroom opinion and juxtapose those results with those attained 13 years prior.

In order to investigate any possible differences, the overall mean collected for each question was compared using t-test statistics (see appendix A). Surprisingly, none of the findings resulted in a significant difference at the < 0.05 level. Understanding that this comparison performed of two individual schools at specific periods of time may provide little valuable data, it is still interesting to see that despite any changes in methodology or pedagogy enacted during the time when these two studies were performed, the reported attitude of both students and teachers is very similar to what was recorded thirteen years prior.

Before discussing the implications of these findings, it is important to explain a few limitations of this study. First, the data collected was taken from an individual high school in Japan and should in no way be taken as a representation of the opinions and expectations for the Japanese education system as a whole. With this, the data was collected from only three of the twenty plus classes that make up the surveyed school. A study taken of the entire attending student body would prove to be an interesting follow up. Also, the surveyed classes consisted of English majors, the 2nd and 3rd year students, and non-English majors, the 1st year students. Although this distinction was noted in the results and tables, this dissimilarity may have affected the overall results of the survey.

Also, it must be noted that not all the results were discussed in this paper. Although noted, (see appendix B) some of the questions (Q14-Q19), were not investigated into nor discussed. After presenting on their results, Tajino and Walker (1998) discuss the effectiveness of a new form instruction they refer to as “team learning”. It is this author’s opinion that these questions were developed and included so that they could help validate this form of methodology and promote its instruction. Because of which, were not addressed in this report. Lastly, some of the essential data from the ALT was absent. Although, the data provided by the ALT was included in the teacher results. Due to time restrictions, it was not possible to follow up on this absence or request for a resubmission of their survey.

In an attempt to affect positive change concerning present team teaching methods, this investigation reveals a positive attitude toward the team-taught English classes carried by the surveyed student body. The lowest recorded response was concerning the students’ general attitude toward the ALT, but even that, with a mean of 3.11, by no means can be defined as negative. With this, it was also revealed that teachers’ expectations are almost entirely correct. Through tables 3-6, it is understood that student opinion presents a traditional role assignment for the JTE and ALT in the classroom, suggesting that the JTE lead when instructing about topics concerning reading and writing and the ALT lead when teaching speaking and listening. Collected data reveals that, almost without exception, teacher role is correctly assigned and performed for these particular classrooms. Perhaps the most interesting data can be seen from what the students do not expect from the JTE. The lack of expected empathy concerning problems related to English certainly was surprising. Perhaps through a follow up study can this be better understood and then effectively addressed. In addition, results show that the overall attitude and opinion toward team teaching and teacher role in the classroom has remained consistent between the two surveyed schools.

Through this study, a better understanding of team teaching has been attained. By better understanding the teacher/student relationship and the expectations carried by both bodies, can the teaching body improve the overall effectiveness that team teaching uniquelyoffers. The team taught classroom is exclusive in that it provides a unique method of instruction of not only a language but also provides a means for students to experience a living representation of a culture associated with that language as well. This uniqueness that the team teaching provides is the reason for its recent upsurge in popularity and also the reason why this methodology requires future research and analysis.

| Student results | Teacher results |

| Q1 | 0.125 | 0.478 |

| Q2 | 0.084 | 0.241 |

| Q3 | 0.412 | 0.449 |

| Q4 | 0.119 | 0.360 |

| Q5 | 0.155 | 0.595 |

| Q6 | 0.126 | 0.251 |

| Q7 | 0.158 | 0.693 |

| Q8 | 0.146 | 0.429 |

| Q10 | 0.170 | 0.658 |

| Q13 | 0.136 | 0.444 |

| Q14 | 0.139 | 0.385 |

Appendix A

t-test results comparing the Tajino and Walker (1998) data with current data

| Q15 | 0.140 | 0.600 |

| Q16 | 0.868 | 0.284 |

| Q18 | 0.245 | 0.391 |

| Q19 | 0.104 | 0.434 |

*data for Q9, Q11, Q12, Q17, Q20 and Q21 was not provided from Tajino and Walker (1998) and therefore was not included

Appendix B Student survey

Team Teaching Questionnaire

(English Translation)

i) Date: /

ii) Sex: M / F

iii) Year: 1st /2nd/ 3rd (age: )

iv) Teachers: JTE ( M / F ) and ALT ( M / F )

JTE= Japanese Teacher of English ALT= Assistant English Teacher

(5 = strongly agree, 3 = neutral, 1 = strongly disagree)

Barratt, L. and Kontra, E. (2000). Native English speaking teachers in cultures other than their own. TESOL Journal 9 (3), 19-23

Brumby, S. and Wada, M. (1990).Team Teaching. Harlow, Essex: Longman

Buckley, F. (2000).Team Teaching: What why and how? Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

JET Programme, Council of Local Authorities for International Relations. (2010). Retrieved from: www.jetprogramme.org

Kumabe, N. (1996). What the introduction of ALTs has brought. Modern English Teaching 33/6: 13.

Manto, K. (1988). Roles of native English speaking teachers in ELT in secondary education.Wakayama University KyoikuGakubu Kiyo Kyoiku Kagaku 44, 115-29.

Medgyes, P. (1992). Native or non-native: Who’s worth more? English Language Teaching Journal 46 (4), 340-9.

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. (2003). Regarding the Establishment of an Action Plan to Cultivate “Japanese with English Abilities”. Retrieved from

www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/houdou/15/03/03033101/001.pdf

Savignon, S. (1983). Communicative competence: Theory and Classroom Practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Shimaoka, T. and Yahiro, K. (1990).Team Teaching in English Classrooms- An Intercultural Approach. Tokyo: Kairyudo

Tajino, A. and Tajino, Y. (2000). Native and non-native: What can they offer? ELT Journal 54/1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tajino, A. and Walker, L. (1998). Perspectives on Team Teaching by Students and Teachers: Exploring Foundations for Team Learning. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 11/1

Wada, M. (1994).Team teaching and the revised course of study. In Wada, M. and Cominos A. (eds) Studies in Team Teaching. (p.7-16). Tokyo: Kenkyusha.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|