Experiential Listening

Michael Tooke, Italy

Michael Tooke is a teacher at the University of Udine in Italy. He has written on English for Academic Purposes and the place of imagination in teaching. His main current interests are the ideas of Rudolf Steiner and their application to education.

E-mail: 1michael.tooke9@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Background

Example

Conclusion

Appendix

References

The obvious aim in any listening course is to help the listener to make sense of what is being said. However, this is not so easy as it sounds as it depends a great deal on having the right attitude and of being able to listen to others without prejudice. We often think we are listening to another person when in fact we are only listening to ourselves.

There are two ways we do this. On the one hand we listen with a preconceived notion of what will be said to us and we listen to what we want to hear, often projecting onto the speaker what we think he is saying. The listening thus serves to confirm our point of view. If we feel the speaker does this we accept what he says, if not we reject it out of hand. In effect we respond in terms of our sympathy or antipathy towards the speaker and in the end create a fantasy out of the listening process. The West has, for example been continuously accused of turning the rest of the world into a counter image of itself (Said, 2003) and there is no doubt a lot of truth in this accusation, but it is one that can in effect be made of all of us.

On the other hand, we can create a specific purpose for ourselves in the listening by designing questions beforehand to address to what we hear and seeking to obtain a practical result from the process. We thus enter the listening with particular aims in mind in order to extract information from it that can be in some way useful to us, the listening thus becoming a means to a technical end. This process serves our own self empowerment, but in so doing it remains at a superficial level where we tend to exploit rather than understand the speaker and his message.

The latter method is the one most often proposed today as it is considered quintessentially practical and scientific. Indeed it is based on the scientific methodology of hypothesis, experiment and testing (Steiner, 1991). However, it is argued here that such an approach necessarily leads to a mechanisation of human relations in which we seek personal affirmation at the expense of others and look for independence via a conscious calculation of self interest. The scientific methodology has become a way of thinking that subjects us to technology (Thiele, 1997).

The skills approach to learning – in our case listening – is just one example of this. Such an approach builds a syllabus around those skills that are supposedly needed to develop listening. These are offered in a sequence on the assumption that their gradual acquisition will enable the learner to achieve mastery over them. The context within which the listening takes place, the content of the listening encounter, the attitude of the listener to the speaker are all downgraded, or entirely ignored, in favour of a succession of eradicated skills that expect the listener to consciously gain expertise in listening. This speaks to the intellect and the power of the learner over the listening process. It dissociates the listener from any participation in the content of a message or in the purposeful interaction with another’s private cosmology. In line with what has been said above it can then foster the egoism and mechanization of understanding that form a fundamental problem in our culture.

There is thus a need for a way out of this impasse. A third way would require a change in basic premises – in reference to the question “Why am I listening?” – and thus our very attitude to the listening process. In this way we search for the purposes of the speaker and try to empathise with their interiority. It requires a different epistemology based not on a distinction between myself and others, but one in which understanding is seen as a mingling of the listener and speaker in an act, not of fantasy, but imagination (Steiner, 1916). In other words, it requires us to put aside sympathy and antipathy and to enter objectively into the world of the other – to start on the search of “correct” rather than “self-serving” opinion. Instead of hearing what we want to hear we have to step into the world in which the other is living. We silence what comes up inside us to block communication. This requires a silencing of any judgement of the other. We suspend our critical faculty, our judging others, in order to walk around with the other in complete attention to what they are saying. Without the ability to attend to another the listening process cannot be pointed in any positive direction.

The rationale of a listening lesson then becomes to develop such abilities in the listener. The teaching of listening is thus basically a moral training in opening oneself to “hearing” what is being said rather than “hearing” what we want to hear. Our ability to go beyond the consensus and our own prejudice, our powers of discernment and our willingness to see exactly where another person is coming from are the fundamental traits for successful listening. Without these no amount of “training” will be productive, except at the most mechanical level. It is also the final aim of listening – have we understood where the person is coming from?

Thus, materials need to be developed that encourage, guide, develop, draw out, foster, enable such an aim. These are the framing forces of each material, which ultimately seeks to change the listener as a person. If there were no such objective at work, it would be a poor, arguably senseless education for listening.

In order to encourage such an attitude of openness to the other, listening has to take place in a context. It does not occur in isolation from other activities but as an integral part of them. The listening might involve an informal conversation, work in a seminar, a problem solving task or taking notes in a lecture to discuss later with colleagues, but it is always a part of an interactive process. The starting point, therefore, for creating materials is to have a context in which to place the listening exercise. This is then followed by a careful analysis of the immediate circumstances surrounding the listening: who the speakers are, their intentions, the results of what they say and the subject about which they are speaking. This may be subsumed under the heading of content. The listening must primarily have content. The purposes of the listening, though much extolled today, is not so important. The purpose, for our purposes, is to develop a right attitude. The content is essential as the instrument for developing this.

The materials then aim to make the learner aware of the content and how it affects the interaction and how it is conveyed through the content. They see how ideas are expressed in the language and what certain language conveys, becoming aware how different linguistic elements (e.g. discourse, functions, pronunciation …) are all used to produce meaning. They are encouraged to look out for meaningful speech and discuss how it is made meaningful. In this was they begin to notice the specific linguistic features that are used in different kinds of speech act.

But such details are suggested in the first place by the context. They belong to the context and arise from it. The syllabus is no longer dictated by an ordered series of skills but created out of specific listening occasions which give rise to particular language features that then feed into further such occasions. Learners come to recognise typical characteristics of certain listening types. They are exposed to content and then develop a sense of the strategies used to create the content, which they can then apply in a further listening.

In providing the context and content and analysing their features, we must not forget that the whole exercise of listening is still an individual event. Different listeners will extract different information, ideas and skills from the same listening. What we point out as worth noticing is only a part of what the listeners will actually notice. It is the act of helping them to notice that triggers the ability to develop their strategies for learning.

It could be argued that this process of listening and analysing constitutes a natural method of learning. Experience is followed by reflection. It recalls aspects of community language methods based on psychological studies of how we learn and reflects how we often learn in our everyday life (Curran 1972, Stevick 1978). Being part of a wider “authentic” context makes it also more vital and in the end a more enjoyable experience than a mere mechanical exercise would be, which links to studies on enjoyment and how it contributes to our learning. Listening is no longer an artificial exercise carried out for its own sake, but part of the overall development of the learner as a person.

This is only confirmed if, as would appear is usually the case, the listening lesson, forming part of a broader curriculum involving work on other aspects of language, is incorporated into an overall theme that organises the learning over a certain period of time into an overarching frame of meaning.

The example lesson (figure 1) comes from a business pre-sessional course preparing business students to start a further degree programme in a variety of disciplines within the University Business School. The syllabus was built around business themes, the theme of this particular week being cross cultural management. The listening was taken from a radio 4 podcast programme called World of Business hosted by Peter Day and the topic was Japanese work culture (Day, 2012).

The programme lasted for about 20 minutes. The first step in preparing materials for the lesson was to listen to it completely without any preconception about the presenter’s position or the content of the piece. This gave some idea of where the presenter was coming from and what he wanted to say as well as suggesting possible parts of the programme and language development that might be suitable for a lesson. A subsequent second listening suggested what extracts from the whole could be taken out for the materials for intensive listening and what sort of exercise would be done with them. These exercises then suggested what other speaking and writing tasks might help the listener focus on the topic. Finally, as the writing of the materials progressed it became clear that the presenter was not just reporting about Japanese work culture so much as making an argument, which he had organised in a very specific way.

In effect the programme, without appearing to be biased in any way, was making the argument that Japan did not have any entrepreneurial culture or skill, that the Japanese much preferred the safety of a permanent job than the insecurity of taking business risks, that this made their culture static and unprogressive and that this could only be negative for their future.

Japanese Work Culture

Peter Day’s World of Business

Pre listening (groups)

What, in the mosaic of world cultures, does Japan contribute to the world? How would you characterise its culture? Can views, like Hofstede’s and others, capture the uniqueness of Japan? What are the differences between Japan and America?

Listening A (00.00 – 08:11) [twice]

The podcast is called Japanese Work Culture. What do you think it will tell us?

Listen and take notes. You will need these notes for later tasks.

(Note: There is the interviewer and two interviewees, so it might be easier to divide your paper into three columns, one for each speaker)

Discuss your notes with a partner, then listen a second time.

Now, using your notes, answer these questions:

What background to the programme does Peter Day give us at the beginning?

What is the aim of the programme?

What two views of failure are presented?

What idea of Japan and America do we have from this extract?

Language

Does Peter Day ask his interviewees direct questions? Why / why not?

How does he introduce their comments?

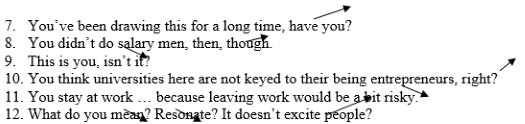

Look at these “questions” Peter Day uses. How do they differ from each other in form/meaning? Note that some “questions” do not end with a question mark.

- You’ve been drawing this for a long time, have you?

- You didn’t do salary men, then, though.

- This is you, isn’t it?

- You think universities here are not keyed to their being entrepreneurs, right?

- You stay at work … because leaving work would be a bit risky.

- What do you mean? Resonate? It doesn’t excite people?

Why does he use these kind of questions? Does the intonation go up or down at the end of each sentence? Why does it do this? Repeat the questions with your teacher and try to imitate the intonation.

Task one

Write down three ideas you have about the cultures of two countries (not Japan or America). Give them to your partner. Look at your partner’s ideas and interview him / her using the forms above (e.g. So, you think the Chinese are more communal than individualistic, do you?)

Do you have the same ideas?

Listening B (17:54-20:24) [twice]

Listen and make notes on Fujio Ichiguro. You will use these notes later.

Discuss your notes with a partner and then listen again and add to your notes if necessary.

Now decide if these are true or false and correct the false statements:

- Fujio studied for an MBA in New York.

- She went to America because it was easier for a working mother there.

- Her company in America sought to help small Japanese start-ups.

- She wanted to return to Japan.

- She started a digital marketing company in Japan because it was a new idea there.

- The Japanese take very few ideas from the US.

What impression does Fujio Ichiguro give of Japan?

Task two

Discuss the following scenario in groups. What do you think is happening here?

The American delegation is getting more and more frustrated with the behaviour of the Japanese team in the negotiations about a joint venture project. The Japanese seem to spend a lot of the meeting discussing things with each other in their own language, and then keep asking the same questions over and over again. For the rest of the time they don’t seem to want to talk at all, so the Americans step in to keep the discussion going. They also seem to be trying to sabotage the deal by asking for very detailed documents.

Listening C (23:30 – 26.40) [once]

Listen and make notes. Then answer the following questions:

What is the mass production mind set?

Why is Japan not capable of creating a new business model?

Task three

From your notes in Listening A, B and C write a summary of the views of Japan given by the three interviewees.

Genre

In what ways is this kind of radio podcast like an academic text?

Identify the following in the podcast:

writer’s hypothesis / initial question; introduction/background; aim (thesis statement);

argument; “citations” in the text;

indications for future research.

What is Peter Day’s argument? What evidence does he have to support his argument?

What unexamined assumption is there?

Do you think this view of Japan is fair? (give evidence for your opinion)

In what ways might it be unfair? (give evidence)

Figure 1: Lesson Plan

|

The format of the programme was a set of interviews with a small number of business people. It became clear that the questions and answers acted like citations in an academic paper. They underlined the presenter’s main point. However, no other point was made except right at the end where it was acknowledged that the Japanese have a very good life style and seem to be able to continue in this way without too much difficulty. Clearly the academic appearance of the programme implied that it was an objective piece of reporting following academic conventions, but a more careful reading demonstrates a bias carefully hidden from the eye (or rather ear). The academic discourse gave a certain gravitas to the argument but in effect concealed major bias. Arguably of course this is, in effect, not so non-academic.

The resulting material (figure one) started with a warmer exercise to elicit possible views of Japan followed by the first listening devoted to a description of, and interview with, one of the informants. This was followed by a focus on the language used in the questions, as these were central to making the argument appear objective while being in effect quotes to support it. This led to an analysis on the intonation patterns involved. The learner was then asked to practise such questions with a partner talking about two other cultures.

This led to the second listening and a second informant with slightly more aggressive views than the first, again followed by a speaking task that not only provided variety from intensive listening practice but also allowed the learner to meditate with a group on the difference between Japanese and Western businessmen. The third listening highlighted the presenter’s main point clearly (the lack of a business spirit in Japan). The penultimate exercise was designed to make the academic format clear to the learner and how the presenter had used it to “good” effect. Finally, the question arose as to how fair this characterisation of Japan was. It took the learner back to the first warmer exercise eliciting different views of Japan and its contribution to world culture.\

In brief, the methodology of the materials requires major focus being given to listening for content and noticing discourse and language features. This, however, involves a careful balance between skills and content, as well as a diversity of tasks to deepen the listening experience and provide variety to the lesson thereby ensuring enjoyable, organic development (Robinson, 2014). The strategies for listening are thus modelled through natural experiences and post listening analysis to recognise the features which are to be noticed and taken into account in the future. Specific study skills, such as note taking or decoding, as well as being part of the materials, can be highlighted as the teacher thinks fit for a particular class. Thus, the strategies for listening are developed in context, modelled in the materials and personalised in class. This should lead to a customised incremental learning process as it gives exposure to natural listening features as well as allowing for the articulation and emphasis of skills as these are required by individual students.

The approach suggested in this article seeks to establish a middle way that avoids mere confirmation of prejudice or mechanical exploitation of the other and fosters a living, flexible, mobile, interactive understanding (of in our case the questions “Who are the Japanese?”) engaging the listener with the subject so that they can enter and walk around the others’ world, noticing on the way how speakers can often obstruct such a process, and thus providing grounds for a human, rather than unreal or mechanistic understanding.

Listening is seen primarily as an attitude in which the sympathies and antipathies of the listener / speaker are overcome and a right opinion and judgement of the other can be attained. Going beyond prejudice leads to a non-egoistic position in which the self moves into the other for a truer understanding of what is being said. Such a process requires a natural context, a situation in which the listening occurs, and a topic about which the listening is concerned. It thus takes the listener through an experience that develops both imagination (heart) and thought (mind) (ibid.) Listening skills, such as decoding , listening for gist and detail, understanding discourse structure and speaker’s viewpoint, arise out of the experience; for if we privilege skills over experience we run the danger of becoming an egoistic, calculating and increasingly utilitarian in our view of others. Experiential listening seeks to overcome such tendencies and foster a deeper understanding and cooperation between speakers and listeners.

Answers to lesson

Japanese Work

Peter Day’s World of Business

Listening A (00.00 – 08:11) [twice]

What background does Peter Day give us at the beginning?

(He talks about a traditional Japanese restaurant with flags indicating that food is being served inside, low light and a cosy atmosphere, for workers returning from work).

What is the aim of the programme?

(the aim is to describe the customs and work habits of a place which is very different from the West)

What two views of failure are presented?

(the Japanese salary man thinks that failure would make him a burden on his family [parents and siblings]. It is a disgrace. The Americanised Japanese says that failure is a prelude to the next success. The opposite of success is not trying. It is not failure)

What idea of Japan and America do we have from this extract?

(America is seen as entrepreneurial and thus ideal for business, while Japan is seen as conservative and thus unable to develop business)

Language

Does Peter Day ask his interviewees direct questions? Why / why not?

(He does not ask direct questions because he is not actually interviewing his informants. He is including some of what they say to further his argument. He is, in effect, quoting them)

How does he introduce their comments?

(He builds up to them as one would with an academic quote)

Look at these “questions” Peter Day uses. How do they differ from each other in form/meaning?

Why does he use them? Does the intonation go up or down at the end of each sentence? Why does it do this?

(Clearly the upward intonation suggests a question, while the downward intonation expects confirmation.)

Listening B (17:54-20:24) [twice]

- Fujio studied for an MBA in New York. (in California)

- She went to America because it was easier for a working mother there. (Yes)

- Her company in America sought to help small Japanese start-ups. (she helped small American start-ups in silicon valley do business with big Japanese firms and vice versa)

- She wanted to return to Japan. (she did not want to return)

- She started a digital marketing company in Japan because it was a new idea there. (Yes)

- The Japanese take very few ideas from the US. (they take most of their ideas from them)

What idea does Fujio Ichiguro give of Japan? (a place to escape from / uncreative)

Task two

The Japanese have numerous discussions with each other. These talks are important for them, since they always aim to create a group consensus (reflecting the high level of collectivism in their culture). This approach is not intended to be rude – indeed, the fact that they are asking questions is a sign that they are taking the negotiations seriously. The habit of creating questions comes from the fact that in Japan people often don’t give a full answer the first time a question is asked. The resultant periods of silence, which tend to disturb the Americans, are a normal part of discourse in Japan, and reflect the fact that is a high-context culture. Any attempt by the American group to keep the discussion going by joining in will be counterproductive. Nor should requests for detailed information be taken as a negative approach, but as a sign that the negotiations are going well – it suggests that key people in the company will want to see this documentation.

[From: Gibson, R. (2000) Intercultural Business Communication Oxford: Oxford University Press]

Listening C (23:30 – 26.40) [once]

What is the mass production mind set?

(making more of the same)

Why is Japan not capable of creating a new business model?

(No reason is given. It seems it is cultural / natural for the Japanese to be uncreative)

Genre

Peter Day starts from the idea that Japan is very different from the West and does not seem to have the same entrepreneurial spirit that one finds in America. He introduces us to a typical restaurant and to a salary man who is also a part time cartoonist, who, however, does not want to leave his salaried job because of the security it gives him.

Peter Day then says he wants to look at the work habits of a country very different from his own. His argument is that, indeed, Japan is unable to be creative and follow a risk taking entrepreneurial spirit.

He uses extracts from his interviews to highlight his argument (as citations). However at the end he admits that Japan looks better now than ever, suggesting perhaps that this would be a good subject for another programme).

The fact that this kind of podcast follows an academic format gives it some “gravitas”. One might argue that is the very search for “gravitas” that leads to the format being adopted in the first place. Unfortunately, like so many academic texts it rests on an unquestioned assumption: in this case that the model of good business practice is that of America. It does not give any indication of what Japan is in itself or what it contributes as such to the world (including the world of business).

Curran, C.A. (1972) Counseling-Learning: A Whole Person Model for Education New York: Grune and Stratton

Day, P. (30 June 2012) Japanese Work Culture The World of Business Available from www.bbc.co.uk/programmes [Accessed on 18 March 2016]

Gibson, R. (2000) Intercultural Business Communication Oxford: Oxford University Press

Robinson, K. Bring in the learning revolution Available from www.youtube.com/watch3/=19elYa3U l [accessed on 30 April 2014]

Said, E. (2003) Orientalism [5th edition] Harmondsworth: Penguin Books

Steiner, R. (1916) The Philosophy of Freedom London: Putnam’s Sons

Steiner, R. (1991) Lo studio dei Sintomi Storici Milano: Editrice Antroposofica

Stevick, E. W. (1978) Memory, Meaning and Method: Some Psychological Perspectives on Language Learning Rowley, Massachusetts: Newbury House

Thiele, L, P. Postmodernity and the Routinization of Novelty: Heidegger on Boredom and Technology Polity, 29 (4) (1997): 489-517

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|