Consciousness-raising Approach in ELT Classroom

Mahshad Tasnimi, Iran

Mahshad Tasnimi is an assistant professor of TEFL at North Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran. She has 15 years of teaching experience. Her main areas of research are second language acquisition, language teaching methodology and testing. E-mail: mtasnimi@yahoo.com

Menu

Introduction

Background

Consciousness-Raising Theory

Consciousness-Raising tasks and their application

Grammar Consciousness-raising Task

Consciousness-raising Tasks As Guided Problem Solving

Consciousness-raising in Data-Driven Learning

Consciousness-raising in teaching genres

Consciousness-raising tasks as input enhancement

CR: Not an alternative but a supplement

Conclusion

References

The notion of consciousness-raising (CR) has given rise to a current debate in pedagogy. The concept of consciousness-raising refers to drawing learners’ attention to the properties of the target language. It equips learners with understanding of specific language features. CR tasks as a concept-forming technique for explicit learning help learners develop declarative and explicit rather than procedural and implicit knowledge. CR tasks engage learners’ minds in the processes of noticing and comparing so that they can integrate new language features into their mental competence.

According to Willis and Willis (2012) and Walsh (2005), in the 1970s and 1980s a body of research in language acquisition suggested that teaching grammatical rules has no effect on language learning, so learners should be left to work out the grammar for themselves.

This debate was traditionally presented by Krashen, who claimed that there is a distinction between conscious learning and unconscious acquisition of language. According to Krashen’s Monitor Model, there are two kinds of knowledge: acquired knowledge and learned knowledge. Acquired knowledge which is implicit is the result of a subconscious process, acquisition. The acquired knowledge is used for communication. Learned knowledge is explicit and is the result of a conscious process, learning. The learned knowledge is of use only when the learner has time to monitor the output. Moreover, Krashen asserts that learned knowledge (explicit knowledge) is completely separate and can not lead to acquisition knowledge (implicit knowledge) (DeKeyser, 2003; Krashen, 1981).

To put it another way, to Krashen language should be acquired through natural exposure, not learned through formal instruction. “It was therefore believed that formal grammar lessons would develop only declarative knowledge of grammar structure, not the procedural ability to use forms correctly” (Nassaji & Fotos, 2004, p. 127). That is to say, explicit grammatical knowledge never turns into implicit knowledge (Nassaji & Fotos, 2004). Truscott (1996, 1998) also rejects the value of explicit grammar teaching and argues that its effects are superficial. This position is referred to as non-interface position (Andrews, 2007; DeKeyser, 2003; Ellis, 1994).

The role of explicit or learned knowledge in the process of language acquisition remains totally debated. Much of the discussion centres on whether or not an interface exists between the learned knowledge and acquired knowledge, explicit knowledge and implicit knowledge, or declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge. The concept of consciousness has put forth as the interface between the two (N. Ellis, 2005), but the question is what consciousness really is.

Actually, underlying the question of the relationship between explicit and implicit knowledge is the question of consciousness. Asserting that the role of unconscious learning in second language acquisition has been exaggerated, Schmidt (1990) points out that the term “consciousness has several senses and is often used ambiguously” (p. 131). He distinguishes several senses of the term: consciousness as awareness, consciousness as intension, and consciousness as knowledge.

Stating that consciousness is often considered synonymous with awareness, Schmidt (1990) distinguishes three levels for awareness. The fist level is perception and is not necessarily conscious, that is “subliminal perception is possible” (p. 132). The second level is noticing which is equated with focal awareness.

The third level is understanding. It involves reflecting and analyzing. In this sense, what has been noticed is compared with what had been noticed previously on other occasions. Schmidt refers to problem solving as an example of this level.

In its second sense, consciousness is considered as intension. Schmidt believes that intensions are not necessarily conscious and that there are occasions where we become conscious of things we do not intend to. To put it another way, not all intensions are conscious.

The third sense is consciousness as knowledge. It refers to what one knows. Walsh (2005) states that a CR activity aims to foster and encourage noticing. Regarding noticing as a trigger for language acquisition, Fotos (1993) mentions four general processing steps:

- a feature in processed input is noticed, either consciously or unconsciously;

- an unconscious comparison is made between existing linguistic knowledge, also called interlanguage, and the new input;

- new linguistic hypotheses are constructed on the basis of the differences between the new information and the current interlanguage; and

- the new hypotheses are tested through attending to input and also through learner output using the new form. (pp. 386-387)

Ellis (1990) and Schmidt (1990) view formal instruction as consciousness-raising. The term consciousness-raising as used by Rutherford and Sharwood Smith (1985), refers to “deliberate attempt to draw the learner’s attention specifically to the formal properties of the target language” (p. 274).

According to Ellis’s (1990) theory, once consciousness of a particular grammatical feature has been raised through formal instruction, learners continue to remain aware of the feature and notice it in subsequent input.

Sharwood Smith (1981, as cited in Walsh, 2005) uses the term consciousness-raising to refer to any kind of grammar which is presented explicitly or inductively. To Sharwood Smith any consciousness-raising needs to go with practice. However, Ellis (1993, 2002b) uses the term specifically to mean a grammar focus activity that doesn’t require the learners to produce sentences in the target language.

Ellis (2002b) differentiates between practice and consciousness-raising. He explains that practice has the following characteristics:

- There is some attempt to isolate a specific grammatical feature for focused attention.

- The learners are required to produce sentences containing the targeted feature.

- The learners will be provided with opportunities for repetition of the targeted feature.

- There is expectancy that the learners will perform the grammatical feature correctly. In general, therefore, practice activities are ‘success oriented’.

- The learners receive feedback whether their performance of the grammatical structure is correct or not. This feedback may be immediate or delayed. (p. 168)

On the other hand, consciousness-raising equips learners with an understanding of a specific grammatical feature. It aims at developing declarative, explicit rather than procedural, implicit knowledge. The following are the main characteristics of consciousness-raising:

- There is an attempt to isolate a specific linguistic feature for focused attention.

- The learners are provided with data which illustrate the targeted feature and they may also be supplied with an explicit rule describing or explaining the feature.

- The learners are expected to utilize intellectual effort to understand the targeted feature.

- Misunderstanding or incomplete understanding of the grammatical structure by the learners leads to clarification in the form of further data and description or explanation.

- Learners may be required (although this is not obligatory) to articulate the rule describing the grammatical structure. (p. 168)

Ellis (1993, 2002b) adds that while practice is mainly behavioral, consciousness-raising is essentially concept-forming. However, these two are not mutually exclusive, forming a continuum. Therefore, “grammar teaching can involve a combination of practice and consciousness-raising” (Ellis, 2002b, p. 169).

As mentioned before, consciousness-raising does not require learners to produce language correctly, but simply to help them ‘know about it’. Ellis (2002b) claims that consciousness-raising facilitates language acquisition. He maintains that the following three processes are involved in the acquisition of implicit knowledge:

- noticing (the learner becomes conscious of the presence of a linguistic feature in the input, whereas previously she had ignored it)

- comparing (the learner compares the linguistic feature noticed in the input with her own mental grammar, registering to what extent there is a ‘gap’ between the input and her grammar)

- integrating (the learner integrates a representation of the new linguistic feature into her mental grammar) (p. 171).

Ellis proves his claim by asserting that the first two processes include conscious attention to language while the third one does not. Furthermore, he states that noticing and comparing can happen at any time and no developmental stages are imposed on them. But integration is subject to psycholinguistic constraints. He maintains that consciousness-raising contributes to the acquisition of implicit knowledge in two major ways. First, “it contributes to the process of noticing and comparing and, therefore, prepares the ground for the integration of new linguistic materials” (p. 171). Second, since consciousness-raising results in explicit knowledge, it helps the learner to continue to notice the feature in the input facilitating its subsequent acquisition. Ellis concludes that consciousness-raising is unlikely to result in immediate acquisition, but it will probably have a delayed effect. Ellis (1994) adds that consciousness-raising avoids the instructional problems of the teachability hypothesis.

Fotos and Ellis (1991) have proposed the use of a task type called the grammar consciousness-raising task. This kind of task is communicative with a grammar problem to be solved interactively. Such a view integrates grammar instruction with the provision of opportunities for meaning-focused use of the language. The aim of CR tasks is raising learners’ consciousness of particular grammatical features through the development of explicit knowledge. In what follows CR tasks and their application are elaborated and illustrated in detail.

Ellis (2003) makes a distinction between two kinds of tasks: focused and unfocused tasks. Focused tasks make learners use a particular structure to complete the task. These tasks are based on a theory of teaching which views language learning in terms of skill-learning; that is, how declarative procedures are transformed into automatic procedures through practice. Such a theory emphasizes:

- The need for declarative knowledge of language to be taught.

- The need for communicative practice, i.e. practice involving ‘real operating conditions’, to proceduralize declarative knowledge.

- The need for feedback that shows learners where they are going wrong. (p. 151)

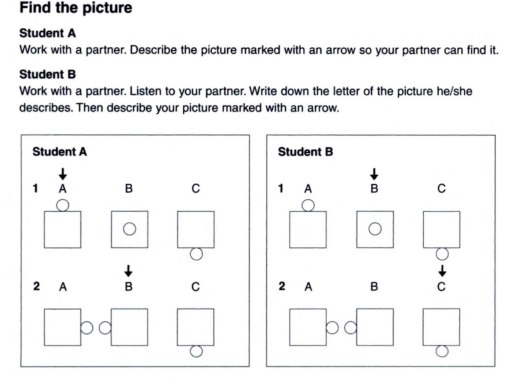

Focused tasks have two aims: a) to stimulate communicative language use (as with unfocused tasks), b) to target the use of a particular target feature. Furthermore, there are two main ways to design a focused task. One is to design the task in a way that “it can only be performed if learners use a particular linguistic feature” (p. 17) for example in the Activity in Figure 1 the learner has to use preposition of place. However, Ellis (2003) believes that it is not easy to design such tasks because learners can make use of some strategies to get the task done. For example, instead of using the preposition ‘on’ they may use ‘not in’. The second way of constructing a focused task, according to Ellis (2003), is making the language itself the content of a task. Ellis refers to these tasks as consciousness raising (C-R) tasks.

Figure 1. An Example of a CR task (Ellis, 2003, p.18)

On the other hand, unfocused tasks predispose learners to choose any linguistic resources to complete the task. Unfocused tasks are based on a theory of teaching which views language as an implicit process that is not influenced directly by instruction but can be facilitated by explicit knowledge. Such a theory emphasizes:

- The need for opportunities to learn implicitly through communication.

- The importance of attending to form when communicating, i.e. ‘noticing’.

- The need to teach explicit knowledge separately as a means of facilitating attention to form. (p. 151)

In designing unfocused tasks, Ellis (2002a) elaborates that although these tasks can be performed without any attention to form, teachers and students may feel the need to attend to various forms incidentally while performing the task. Here, of course, attention is extensive rather than intensive, that is different forms are treated briefly.

As mentioned above CR tasks are a kind of focused tasks. Ellis (2003) states that C-R tasks differ from other focused tasks (such as structure-based production tasks and comprehension tasks) in two essential ways: first, C-R tasks primarily emphasize explicit learning, whereas the other kinds of focused tasks focus on implicit learning. To make the term ‘explicit learning’ clear, Ellis refers to Schmidt’s (1990) levels of awareness (perception, noticing and understanding) and states that explicit learning means developing “awareness at the level of ‘understanding’ rather than awareness at the level of ‘noticing’” (p. 163). Second, C-R tasks do not build around the content, but they make language itself the content.

In designing C-R tasks, the first step is isolating a specific linguistic feature for attention. Second, the learners are provided with input illustrating the feature and they may also be given a rule to explain the feature. Then, they are supposed to understand the targeted feature. Finally, learners are required to describe the grammatical structure in question. Since learners are supposed to talk about the data together, Ellis uses the term ‘task’ rather than ‘activity’. He states, “although there is some linguistic feature that is the focus of the task learners are not required to use this feature, only think about it and discuss it” (pp. 163). Fotos (1994) adds that C-R tasks are communicative because learners are required to focus on meaning as well as form. Ellis (2003) adds, “A C-R task constitutes a kind of puzzle which when solved enables learners to discover for themselves how a linguistic feature works” (p. 163). Comparing focused tasks with activities which emphasizes focus on forms, Ellis (2002a) asserts:

This type of focus-on-form instruction is similar to focus-on-forms instruction in that a specific form is pre-selected for treatment but it differs from it in two key respects. First, the attention to form occurs in interaction where the primary focus is on meaning. Second, the learners are not made aware that a specific form is being targeted and thus are expected to function primarily as ‘language users’ rather than as ‘learners’ when they perform the task. (p. 421)

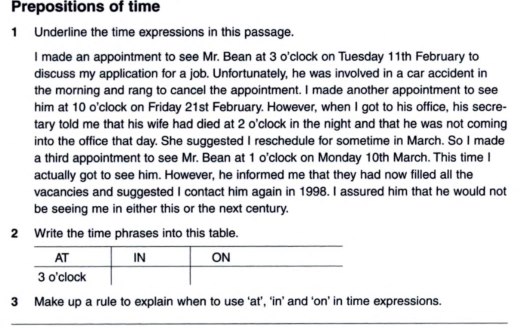

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate examples of CR tasks.

Figure 2. An Example of a CR task (Ellis, 2003, p.18)

Figure 3. An Example of a CR task (Nunan, 2004, p. 99)

Ellis (1993) identifies two kinds of CR tasks: CR tasks for comprehension and CR tasks for explicit knowledge. The former is aimed at focusing the learners’ attention on the meaning conveyed by specific grammatical features. It is suggested that this type of CR tasks help learners to internalize those features as implicit knowledge. The latter is targeted at helping learners “learn about a particular grammatical feature by developing an explicit representation of how it works in the target language” (p. 109)

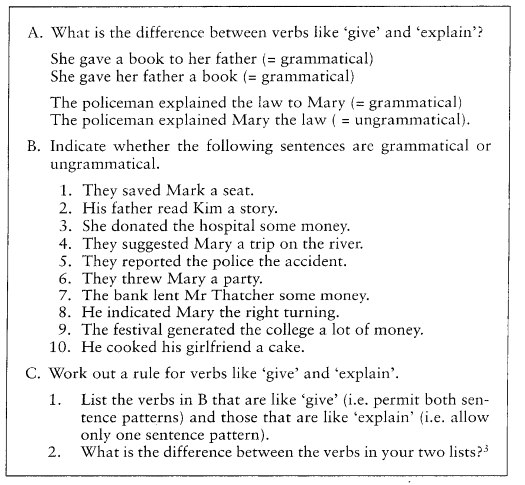

In another classification, Ellis (2002b) makes a distinction between inductive and deductive CR tasks. In the case of the former, the learner is asked to construct an explicit rule to describe the grammatical features which the task demonstrates. In the case of the latter, the learner is provided with a rule and then he or she is supposed to carry out some task. Figure 4 provides an example of an inductive task.

Figure 4. An Example of an inductive CR task (Ellis, 2002b, p.173)

Willis and Willis (2012) introduces CR tasks as guided problem solving which help learners to “notice particular features of the language, to draw conclusion from what they notice and to organize their view of language in the light of the conclusions they have drawn” (p. 2). Furthermore, they add that the three part process of observe, hypothesize and experiment is involved in doing CR tasks. They exemplify the following CR tasks:

Identify/consolidate

Students are asked to search a set of data to identify a particular pattern or usage and the language forms associated with it.

Classify (semantic; structural)

Students are required to work with a set of data and sort it according to similarities and differences based on formal or semantic criteria.

Hypothesis building/checking

Students are given (or asked to make) a generalization about language and asked to check this against more language data.

Cross-language exploration

Students are encouraged to find similarities and differences between patternings in their own language and patternings in English.

Reconstruction /deconstruction

Students are required to manipulate language in ways which reveal underlying patterns.

Recall

Students are required to recall and reconstruct elements of a text. The purpose of the recall is to highlight significant features of the text.

Reference training

Students need to learn to use reference works - dictionaries, grammars and study guides. (p. 7)

They believe that CR tasks can be based on both a written and a spoken text. The following are examples of CR tasks based on a written text (Willis and Willis, 2012, pp. 9-10).

Auto-pilot

The flight ran several times a week taking holiday-makers to various resorts in the Mediterranean. On each flight, to reassure the passengers all was well, the captain would put the jet on to auto-pilot and he and all the crew would come aft into the cabin to greet the passengers.

Unfortunately on this particular flight the security door between the cabin and the flight deck jammed and left the captain and the crew stuck in the cabin. From that moment, in spite of efforts to open the door, the fate of the passengers and crew was sealed.

|

- List all the phrases to do with aircraft and flying. What word occurs in nearly all these phrases? Why?

- What does would mean in the second sentence?

- What about ran in the first sentence? Would used to run give the same

meaning? What about jammed and left in the second paragraph? Could used to be used here?

- Cover your original text. Read the rewritten version of the text below. How has it

been changed from the original?

- Would: Review

Here are some sentences with would which you have seen before. Find sentences in which

- would is used as a conditional.

- would is the past tense of will.

- would means `used to'.

How many sentences are left over?

a If you were designing a poster which two would you choose?

b Yes, I would think so.

c My brother would say, `Oh your mother spoils you.'

d Would you like to ask us anything about it?

e Yes, yes, I would agree with that certainly.

f Not the sort of letter I would like to receive.

g Would people in your country talk freely about these things?

h Then we said that we would play hide and seek.

i Often there would be a village band made up of self-taught players.

j Some would write their own songs or set new words to tunes.

k What advice would you give to a young person leaving school or University?

1 That's right, yes, and it would slow the ship down.

m I never had the light on. My parents wouldn't allow it.

n But now a new fear assailed him. Would he get caught in the propeller?

o This brief report would best be understood by a listener who had read the earlier story.

Willis and Willis (2012) assert that CR tasks encourage learners to observe and analyze language for themselves, making sense of it.

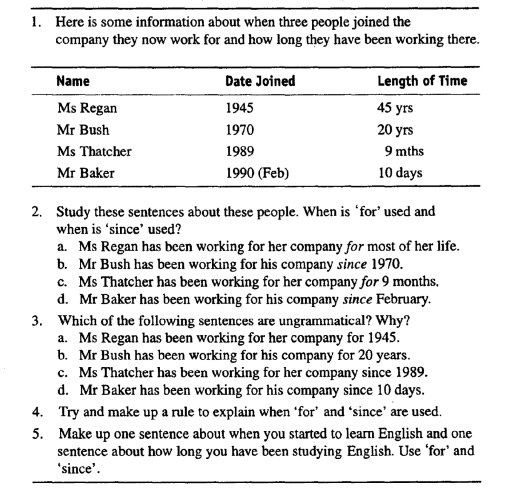

Another application of consciousness-raising can be found in Data-Driven Learning (DDL). DDL is an inductive approach to learning in which learners are involved in researching corpora through the use of concordancers (Beatty, 2003). Concordancer is an important tool (software) in corpus linguistics which can find every occurrence of a particular word or phrase. With a computer, we can search millions of words in seconds. The search word or phrase is often referred to as the key word or node and concordance lines are usually presented with the key word/phrase in the centre of the line with seven or eight words presented at either side. These are known as Key-Word-In-Context displays (or KWIC concordances) (O’Keeffe, McCarty, and Carter, 2007). Fox (1998) and Willis (1998) state that analysis activities which are based on concordance lines can be used as consciousness-raising activities, providing learners with opportunities to discover language before expecting them to produce it. Furthermore, they help learners to note the gap between their use of a word and the way(s) native speakers use it (see Figure 5).

Using concordancers help learner become more aware of language and pay more attention to forms rather than simply use them. This noticing help learners reflect on further occurrences of language items that have been made salient through concordancing. There is likelihood that this awareness will increase proficiency (Fox, 1998; Lamy and Mortenson, 2012).

IMG

Figure 5. Concordance lines for freezing point with some exercises for analyzing the phrase

(Hunston, 2002, p.179)

Yet, another application of consciousness-raising is in teaching genres. Hyland (2006) states that genres play a central role in any methodology. He suggests teachers to illuminate the genres that are important for students. Analyzing different texts and contexts help raising students’ awareness about different genres. He recommends that one way of doing this is asking students in small groups to analyze, compare and manipulate samples of the target discourse in a process known as ‘rhetorical consciousness-raising’. Hyland introduces consciousness-raising as a top-down approach to learning language, focusing on language not as an end in itself but as a means to an end. Consciousness-raising encourages learners to experience language for themselves.

Hyland adds that consciousness-raising help learners to create, comprehend and reflect on language as discourse. It assist them to “explore key lexical, grammatical and rhetorical features and to use this knowledge to construct their own examples of the genre. Consciousness-raising is therefore designed to produce better writers and speakers rather than better texts” (p. 90). This approach addresses the way meaning is constructed. He maintains that although in this approach some particular text elements are highlighted, they are not isolated from the overall meaning of the text. Hyland mentions the following examples for comparisons and attention to language use in discourse where students:

- Compare spoken and written modes, such as a lecture and textbook, to raise awareness of the ways in which these differ in response to audiences and purposes.

- List the ways that reading and listening to monologue are similar and different.

- Investigate variability in academic writing by conducting mini-analyses of a feature in a text in their own discipline and then comparing the results with those of students from other fields.

- Survey the advice given on a feature in a sample of style guides and textbooks and compare its actual use in a target genre such as a student essay or research article.

- Explore the extent to which the frequency and use of a feature can be transferred across the genres students need to write or participate in.

- Reflect on how far features correspond with their use in students’ first language and on their attitudes to the expectations of academic style in relation to their own needs, cultures and identities. (p. 90)

Sharwood-Smith (1991) refers to CR tasks as ‘input enhancement’. He defines input enhancement as “the process by which language input becomes salient to learners” (p. 118). This process can be done through different activities such as highlighting, underlining, color coding, bold facing, using error flags and the like. CR tasks, which are oriented toward input enhancement, draw learners’ attention to the target language forms to make particular L2 forms more salient. For instance, irregular past form of the verbs could be bolded or underlined to deliberately make the target forms in the input enhanced by visually altering their appearance in the text.

Sharwood-Smith (1993) introduces two types of input enhancement: positive and negative. In positive input enhancement the correct forms are highlighted whereas in negative input enhancement the incorrect forms are enhanced. The example provided in the previous paragraph about irregular past form of the verbs is an example of the positive input enhancement. For negative input enhancement, for example, the instructor may use error flags to draw learners’ attention to their errors and mistakes.

To reiterate the value of CR tasks, they provide learners with opportunities to communicate while promoting subsequent noticing of the grammatical features (Ellis, 2003). However, as Ellis mentions, CR tasks do not seem well-suited to young learners who would like to do something with language rather than to study. Additionally, learners who lack metalanguage may find these tasks difficult to do. Finally, CR tasks may not appeal to learners who are not skilled enough in forming and testing hypotheses about language. Therefore, Ellis (1991 as cited in Ellis, 2003) concludes that “consciousness-raising is not an alternative to communication activities, but a supplement” (p. 167).

A number of studies have proved the effectiveness of CR tasks in developing explicit knowledge. In a study, Fotos and Ellis (1991) compared the effects of direct consciousness-raising with indirect consciousness-raising. Grammar explanations were used for the former, while CR tasks were applied for the latter. They found that both methods resulted in considerable gains in understanding of the target structure. However, the direct method seemed to produce the more durable gains. Nevertheless, in another study Fotos (1994) did not find any significant difference between these two methods.

In conclusion, consciousness-raising involves an approach that is in agreement with progressive views about education as a process of discovery through problem-solving tasks. The merits of CR tasks are prominent; therefore, they can be applied in pedagogy and classroom practices as a suitable supplement for communicative activities.

Andrews, S. (2007). Teacher language awareness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beatty, K. (2003). Teaching and researching computer-assisted language learning. New

York: Longman.

Dekeyser, R. (2003). Implicit and explicit learning. In C. J. Doughty & M. H. Long

(Eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 313-348). Malden, USA: Blackwell Publishing.

Ellis, N. (2005). At the interface: dynamic interactions and explicit and implicit language

knowledge. Studies in second language acquisition, 27 (2), 305-352.

Ellis, R. (1990).Instructed second language acquisition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Ellis, R. (1993). The structural syllabus and second language acquisition. TESOL

Quarterly, 27 (1). 91-113.

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Ellis, R. (2002a). Does form-focused instruction affect the acquisition of implicit

knowledge. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24, 223-236.

Ellis, R. (2002b). Grammar teaching: Practice or consciousness raising? In J. C.

Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in language teaching (pp. 167-174). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Fotos, S. (1993). Consciousness-raising and noticing through focus on form:

Grammar task performance vs. formal instruction. Applied Linguistics, 14(4), 385-407.

Fotos, S. (1994). Integrating grammar instruction and communicative language use

through grammar consciousness-raising tasks. TESOL Quarterly, 28(3), 323-351.

Fotos, S., & Ellis, R. (1991). Communicating about grammar: A task-based

approach. TESOL Quarterly, 25(4), 605-628.

Fox, G. (1998). Using corpus data in the classroom. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Materials

development in language teaching (25-42). Cambridge: CUP.

Hunston, S. (2002). Corpora in applied linguistics. Cambridge: CUP.

Hyland, K. (2006). English for academic purposes. New York. Rutledge.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. Oxford:

Pergamon.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). Understanding language teaching: From method to

postmethod. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lamy, M., & Mortensen, H. J. (2012). Using concordance programs in the modern

foreign language classroom. Retrieved may 11, 2012, from http://www.ict4lt.org/ en/en_mod2-4.htm

Nassaji, H., & Fotos, S. (2004). Current developments in research on the teaching of

grammar. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 126-145.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

O’Keeffe, A., McCarty, M., Carter, R. (2007). From corpus to classroom: language use

and language teaching. Cambridge: CUP.

Rutherford, W., & Sharwood-Smith, M. (1985). Consciousness raising and Universal

Grammar. Applied Linguistics, 6(3), 274-282.

Schmidt, R. W. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied

Linguistics, 11 (2). 129-158.

Sharwood Smith, M. (1991). Speaking to many minds: On the relevance of different types of

language information for the L2 learner. Second Language Research, 7 (2), 118-132.

Sharwood Smith, M. (1993). Input enhancement in instructed SLA. Studies in Second Language

Acquisition, 15, 165-179.

Truscott, J. (1996). The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes. Language

Learning, 46 (2), 327-369.

Truscott, J. (1998). Noticing in second language acquisition: A critical review. Second

Language Research, 14 (2), 103-135.

Walsh, M. (2005). Consciousness-raising (C-R): its background and application.

Retrieved June 7, 2014, from http://www.walshsensei.org/Walsh2005CR.pdf.

Willis, J. (1998). Concordances in the classroom without a computer: Assembling and

exploiting concordances of common words. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Materials

development in language teaching (44-66). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Willis, D., & Willis, J. (2012). Consciousness-raising activities. Retrieved June 7, 2012,

from http://www.willis-elt.co.uk/documents/7c-r.doc.

Please check the English Update for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|