The Influences of Recreational Reading in a Native Language on Foreign Language Learning

Selami Aydin, Turkey

Selami Aydin is an associate professor at the Department of English Language Teaching at Balikesir University, Turkey. His research has been mainly in EFL writing, language testing, affective factors and technology in EFL learning and teaching.

E-mail: saydin@balikesir.edu.tr

Menu

Introduction

Method

Qualitative research

Descriptive research

Results

Conclusions and discussion

References

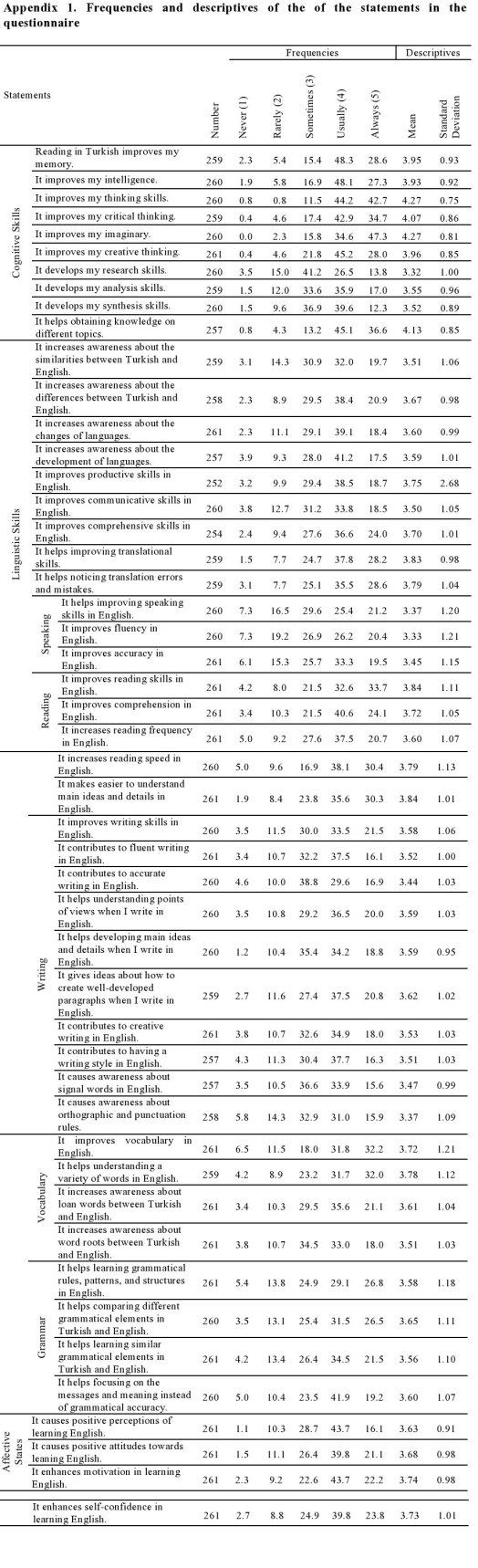

Appendix 1. Frequencies and descriptives of the of the statements in the questionnaire

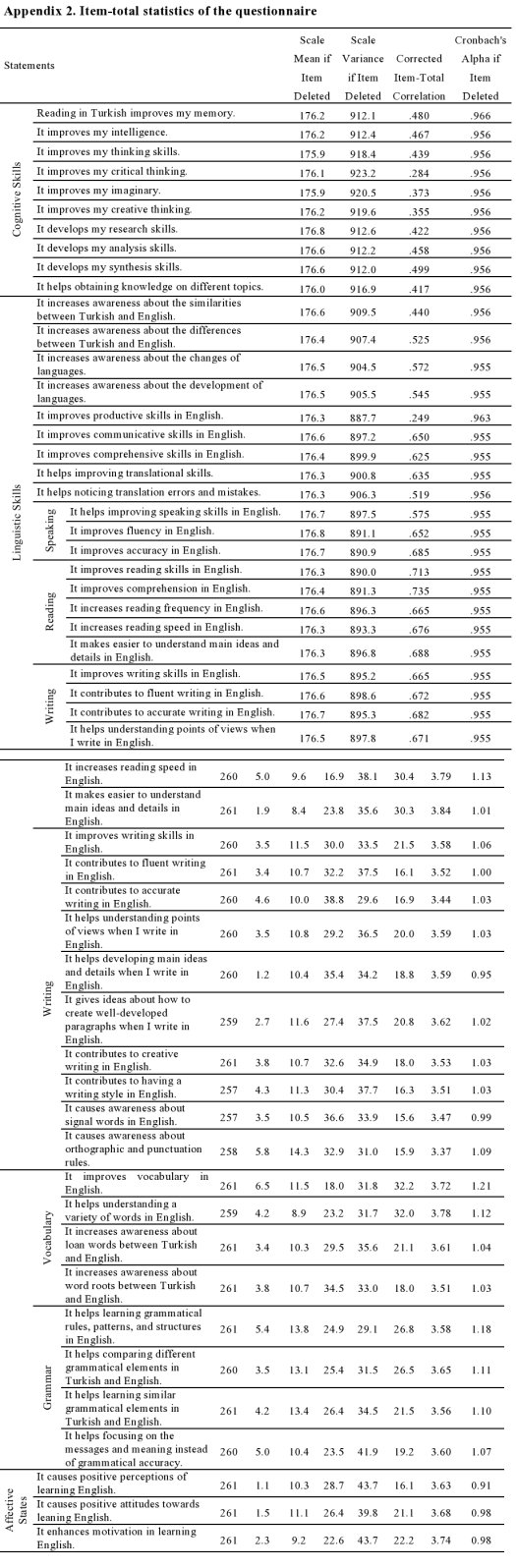

Appendix 2. Item-total statistics of the questionnaire

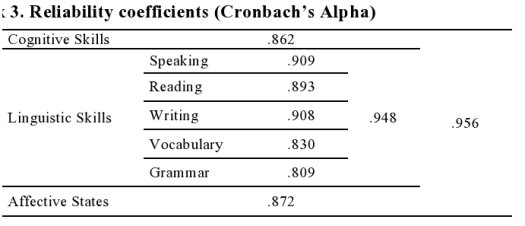

Appendix 3. Reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s Alpha)

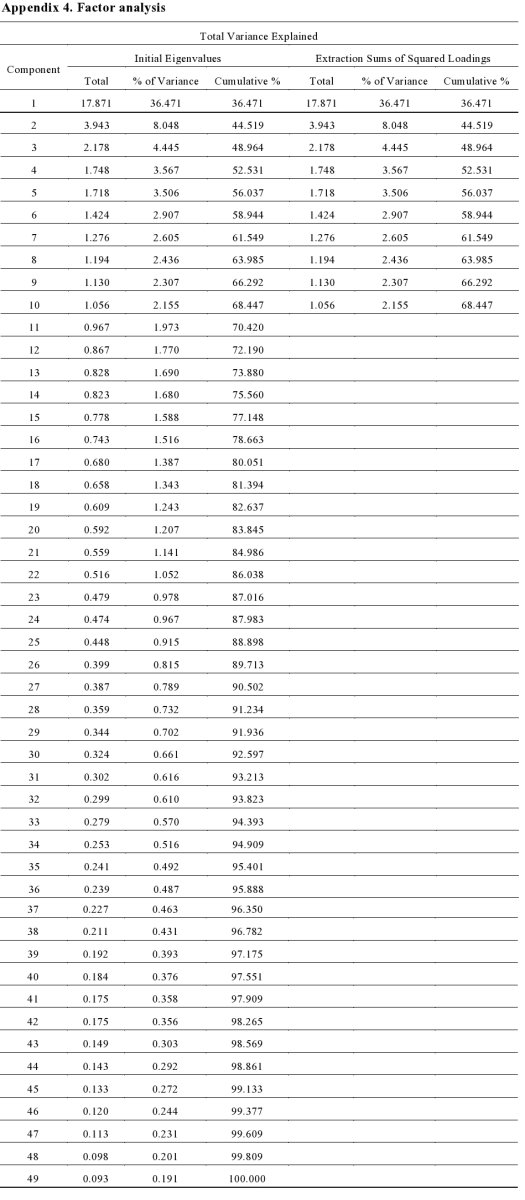

Appendix 4. Factor analysis

As Holden (2004) notes, reading is a very important gateway to personal development and to social, economic and civic life. It helps students learn about people, history, languages, science, mathematics, and all other content. Reading is also one of the main language skills, and it promotes language acquisition and learning. Recreational reading improves autonomous learning, creativity, intelligence, comprehension, communicative competence, literacy development, motivation, and attitudes towards language learning. It is also obvious that reading enjoyment has declined significantly in the last years (Sainsbury & Schagen, 2004) and that tests have discouraged students from reading for pleasure (Powling, Gavin, Pullman, Fine, & Ashley, 2003).

Two problems arise with regard to recreational reading in the native language and its effects on the foreign language learning process. First, as reviewed below, fairly limited studies have been conducted on the effects of recreational reading in the native language on foreign language learning. Research has mainly focused on the effects of reading in the second or a foreign language on ESL and EFL acquisition and learning processes. Second, among the limited studies on the effects of recreational reading in L1 on EFL learning, reviewed below, no study was found on the effects of Turkish as a native language on EFL learning. Thus, the current paper examines the effects of recreational reading in Turkish as a native language on the EFL learning process.

The studies on recreational reading can be categorized in terms of native, second and foreign language. The current section reviews previous research on recreational reading in English as a native language. It also presents a review on recreational reading in English as a second and foreign language. Last, it reviews studies on recreational reading in a native language and its effects on the foreign language learning process.

In a broader perspective, the studies on recreational reading in English as a native language have focused on the relationships between the reading process and certain factors such as race, socioeconomic factors, reading environment, amount of reading, attitudes, autonomy, creativity and intelligence. With regard to reading frequency, Gunter (1994) found that students read at least one book per week during their free time. Corridon (1994) noted that some students had positive attitudes towards recreational reading in English as a native language, while some maintained the opinion that reading is a boring activity. Additionally, the data obtained from a different study (Ageletti, Hall, & Warmac 1996) demonstrated that an overload in the school curriculum, parental values regarding recreational reading, modern technology, and available resources were correlated with the amount of time students spent reading for pleasure. In another example, McCarthy, Nicastro, Spiros and Staley (2001) found that students’ recreational reading habits improved, their desire for their teacher to read aloud to them on a daily basis increased, and their reading habits at home were positively influenced. In terms of autonomy and creativity, Burnett and Myers (2002) noted that, while children’s literacy reflected community literacy practices, children acted with considerable autonomy and creativity in their reading choices. Lastly, Buschick, Shipton, Winner and Wise (2007) found that there was an increase in the number of students reading at home, visiting a library, and feeling comfortable and confident when approaching a new word in reading.

The studies on recreational reading in ESL have focused on certain factors such as achievement, time of reading, age, language development, comprehension, communicative competence, acquisition and literacy development, and attitudes. Pichette (2005), for instance, examined the relationship between time spent on reading and reading comprehension in ESL acquisition. The results revealed that low-proficiency learners showed low, non-significant correlations between the time spent on reading English and English reading comprehension, while correlations for high-proficiency learners were moderate and significant. In addition, the findings suggested that if ESL reading is used to enhance L2 reading development, it may not serve that purpose effectively for beginning and intermediate learners whose working memories are still taxed by word decoding processes. Similarly, Greenberg, Rodrigo, Berry, Brinck, and Joseph (2006) investigated whether the extensive reading approach utilized with ESL learners could be applied in a classroom for adults who have difficulty with reading. In addition, Constantino (1995a) described how reading for pleasure for 20 minutes of each class period in a beginning and intermediate-level reading course for adult ESL learners resulted in language development in terms of reading, writing, and comprehension, as well as increased confidence. Also, Crandall, Jaramillo, Olsen, and Peyton (2002) described ways to develop students' English language and literacy skills and to make academic content challenging, interesting, and accessible. They noted that free reading presents an opportunity for second language development. Moreover, Chang and Krashen (1997) argued that free reading in a second language outside of school makes an important contribution to literacy development and academic achievement, and that it is responsible for competence in writing style as well as other aspects of literacy. Krashen (1997) also argued that voluntary free reading has a place in programs whose primary goal is the development of academic second-language competence. Finally, Constantino (1995b) supported Krashen's theory on the benefits of voluntary free reading and the impact pleasure reading makes on TOEFL results. The improved TOEFL scores indicated a measurable and viable result of reading for pleasure as well as an intangible attitudinal change on the part of the students.

In terms of English as a foreign language, some studies examined the relationship between recreational reading in EFL learners and certain factors such as time reading, achievement in foreign language learning, motivation, attitudes, creativity, vocabulary acquisition, and vocabulary size. To provide an example, Raemer (1996) underlined that students who read more will eventually surpass their classmates who have not developed reading habits. Tercanlioglu (2001) examined the nature of Turkish students' motivation to read. The study findings suggested that students read both for extrinsic and intrinsic reasons. Yang (2001) investigated the effects of reading mystery novels on adult EFL learners studying English for the purposes of pleasure or career development. The results showed that novel readers made substantial proficiency gains and that there were important motivational benefits as well. As an example of the relationship between attitudes and recreational reading in English as a foreign language, Cho and Krashen (2001) described how a single positive experience in self-selected reading of children's books resulted in a profound change in attitudes toward recreational reading among Korean teachers in EFL learning. They found that, after the experience, nearly all the teachers reported that they were interested in using sustained silent reading in their classes. With regard to creativity, Wu (2000) used journals and image notebooks to examine EFL learning university students' cognitive skill development as they completed pleasure-reading activities that preceded creative writing tasks. The results suggested that the students were successfully empowered to create their own short stories by using the writing skills they learned from extensive reading of mystery or detective stories both in and out of class. Last, in terms of vocabulary, Bray (2002) looked into the design, implementation, and integration of a task journal in EFL classes to promote reflection on the reading process and to offer students practice with a practical strategy for vocabulary building and discussed the role of independent reading. Similarly, Hsueh-Chao and Nation (2000) examined the percentage of text coverage needed for unassisted reading for pleasure.

A limited number of studies have been conducted on the effects of recreational reading in native language on foreign language learning, while no study was found on the effects of recreational reading in Turkish as a native language on the EFL learning process. Among the available studies, Cevellos (2008) described how one subject’s experience as a poor reader who did not like to read in elementary school. The subject credited self-selected reading for her improvement as a student in her native Ecuador and gave reading much of the credit for her competence in English. The findings of the study indicated that there exists a transfer across native and foreign languages and that reading in a native language creates competence in that foreign language. With regard to Turkish as a native language and its effects on EFL learning, Oncu (1998) descriptively analyzed strategy use in Turkish and EFL reading, while Kurtul (1999) focused on the effects of culture and reading skills in Turkish on foreign language literacy. Moreover, as previously mentioned, Tercanlioglu (2001) examined the nature of Turkish students' motivation to read. Finally, Aydin (2003) examined the feasibility of transference between native and foreign languages with regard to reading strategies.

In conclusion, the studies demonstrated that recreational reading in English as a native language has significant contributions to the development of readers in terms of autonomy, creativity and intelligence, whereas recreational reading in ESL has positive effects on language achievement, language development, comprehension, communicative competence, acquisition, literacy development and attitudes. Finally, the results of the studies on recreational reading in EFL learners show that time spent reading, achievement in foreign language learning, motivation, and attitudes are significant factors that affect the reading process and improve vocabulary acquisition. However, it should be noted that few studies were found on the effects of recreational reading in a native language on the EFL learning process. The limited studies available show that reading skills transfer across the two languages and that recreational reading in a native language creates competence in a foreign language. On the other hand, no study was found on the effects of recreational reading in Turkish as a native language on the EFL learning process. Other studies focused on: (1) the use of inference as a reading strategy and its effect on proficiency in reading and figuring vocabulary meanings from context; (2) strategy use in Turkish as a native language and EFL reading; (3) the effect of culture on foreign language literacy; and (4) feasibility of transference between a native language and a foreign language with regard to reading strategies. Therefore, there are two reasons to conduct the present study. First, it can be noted that it does not seem possible to draw conclusions from studies that focus on the effects of recreational reading in a foreign language on reading in a native language and its influences. Second, as previously mentioned, no study of Turkish as a native language and its effects on EFL learning was found. Thus, there is a strong need to examine this issue. The current study aims to research the effects of recreational reading in Turkish as a native language on the learning process of English as a foreign language and has one research question: Does recreational reading in Turkish as a native language affect the learning process of English as a foreign language?

The research consisted of two main procedures. The first part of the study included a qualitative procedure used to design a questionnaire aimed at measuring the perceptions of EFL learners in terms of the contributions of recreational reading in the L1 to EFL learning process. The second procedure was designed to collect and analyze the descriptive data obtained from the questionnaire. The details of these research procedures are presented in two subsections.

The sample group for the qualitative study consisted of 70 EFL students in the English Language Teaching Department (ELT) at Balikesir University. All students were freshmen in the ELT department, as writing and reading classes are taught only during the first year of the teaching program. The group consisted of 57 (81.4%) females and 13 (18.6%) males whose mean age was 19.1 with a range of 18-22.

The qualitative study used a three-step procedure: recreational reading in Turkish, data collection and data analysis.

- Recreational Reading in Turkish: During the first semester of the 2009-2010 academic year of, each student read five books in his or her free time. The students were free to select the works and writers. In total, they read 350 books by 71 writers, 112 of which were works by Turkish writers and 238 of which were works translated into Turkish.

- Data Collection

: Five instruments were used to ensure the validity of the data: oral presentations, classroom discussion, interviews, essay papers, and their responses to examination questions. After reading each book, the students prepared weekly notes that reflected their perceptions of recreational reading, presented their opinions in five-minute presentations, and discussed their ideas in classroom sessions without interruption by the researcher, who only took notes. The participants then prepared two essays on the effects of the reading process on EFL learning. Then, the researcher interviewed the students in small group sessions about the issue. At the end of the semester, the students responded to two questions about the effects of recreational reading on the EFL learning process in their final examination.

- Data Analysis: The data obtained from each source were analyzed separately. That is, the data from each of the sources were transferred into five concept maps to compare the statements and numbers; a comparison of the concept map indicated data validity. Then, the data from the five maps were combined and presented in numbers and frequency percentages in a table. At the end of the qualitative process, a questionnaire was developed for use in the descriptive study.

The sample group in this part of the study consisted of the 261 students studying in the ELT department of Balikesir University. Of the participants, 201 (77%) were female students and 60 (23%) were male. The gender distribution in the sample group was similar to the distribution in the department. The mean age was 20.28, with a range of 17 to 30. The group included 87 (33.3%) freshmen, 70 (26.8%), sophomores, 55 (21.5%) juniors, and 48 (18.4) seniors. In addition, 216 (82.8%) participants stated that they liked reading in their free time, while 41 (15.7%) of them did not. Lastly, the mean score for the number of books they read in a month was 2.01, and the mean for the number of pages read each day was 36.43.

The data collection instruments consisted of a background questionnaire and the Questionnaire of Perceptions of Recreational Reading in a Native Language. The background questionnaire probed the students about their gender, age, and grade, how many books they read, how often they read, and whether they liked reading in their native language or not. The Questionnaire of Perceptions of Recreational Reading in a Native Language consisted of items examining the students’ perceptions of the effects of recreational reading in Turkish on the EFL learning process. The items were assessed on a scale ranging from one to five (never = 1, rarely = 2, sometimes = 3, usually = 4, always = 5).

After designing the questionnaire in accordance with the data obtained from the qualitative research, it was administered to 15 senior students in the department to identify and correct any misconceptions and to obtain moderation of the questionnaire. Then, after obtaining formal permission from the faculty administration, the questionnaire was administered in the Fall semester of the 2010–2011 academic year. The data collected were analyzed using SPSS software. The reliability coefficient of the Questionnaire of Perceptions of Recreational Reading in a Native Language was 0.956 in Cronbach’s Alpha. The reliability coefficients of the sub-groups and item-total statistics of the questionnaire are shown in Appendices 3 and 4. The reliability coefficients of the sub-factors in the questionnaire were in the range of 0.809 to 0.948. In addition, the item-total statistics indicated that each of the items had a high level of reliability in the range of 0.955 to 0.956 and that the scale had internal consistency. In summary, the values indicated that the questionnaire had a high level of reliability. The factor analysis also demonstrated that the factors in the questionnaire were similar to ones obtained from the qualitative data. Thus, no statements from the questionnaire were invalid (Appendix 4). As for the statistical analysis of one research question, the data were examined to see the frequencies in percent, means and standard deviations were used to describe participants’ perceptions (Appendix 1).

According to the findings presented in Appendix 1, recreational reading in L1 has considerable effect on EFL readers’ cognitive and linguistic skills and affective states. First, it contributes significantly to their thinking skills and memory. Second, it makes considerable contributions to their speaking, reading and writing skills, and their knowledge of grammar and vocabulary. Last, it has positive effects on their attitudes towards EFL learning and improves their motivation and self-confidence.

Students believe that recreational reading makes considerable contributions to their cognitive skills. Specifically, they state that reading in Turkish improves their memory, intelligence, and imagination. Moreover, they think that reading in L1 is beneficial to improving their critical and creative thinking skills. They also emphasize that recreational reading in Turkish is useful to develop their research, analysis and synthesis skills. Last, they believe that reading in L1 helps them obtain knowledge about different topics.

Another contribution recreational reading makes is related to EFL readers’ linguistic skills. The participants believe that it increases awareness about the similarities and differences between Turkish and English as well as the changes and development of languages. For them, reading the translated works from other languages to Turkish improves their translation skills and helps them notice translation errors and mistakes. In terms of speaking, EFL learners think that reading in Turkish improves their fluency and accuracy in Turkish. They highlight that it improves comprehension skills in English, increases their reading frequency and speed in reading in English, and makes it easier to understand the main ideas and details in texts written in English. One of the contributions recreational reading in L1 makes is to the writing skills of EFL learners. That is, it contributes to fluency and accuracy of English writing, helps develop the main ideas and details during their writing process, and facilitates an understanding of the points of views in written pieces. Furthermore, EFL learners state that reading in Turkish makes them creative when they write, contributes to their style, and increases awareness about transition words, orthographic and punctuation rules. In terms of vocabulary, the learners believe that reading in L1 helps them to understand a variety of words in English as well as loan and root words roots between the two languages. Recreational reading also contributes to the grammatical knowledge of EFL learners. In other words, learners think that once they learn grammatical rules and structure patterns in English, they can compare the different and similar grammatical elements in the two languages, and focus on the message and meaning rather than on grammatical accuracy.

Finally, recreational reading in Turkish has some significant effects on the affective states of EFL learners. Specifically, it considerably enhances motivation and self-confidence in the EFL learning process. In addition, it creates positive perceptions and attitudes towards learning English.

Three main results were obtained from the research. First, recreational reading in Turkish has positive effects on students’ cognitive skills. In other words, EFL learners perceive that recreational reading in Turkish improves their memory, intelligence, imagination, critical and creative thinking skills, and research, analysis and synthesis skills. Second, recreational reading in Turkish has positive effects on their linguistic skills. That is, it contributes to the awareness of the similar and different points between the two languages and to the changes and development of languages as well as their translational skills. Furthermore, recreational reading in Turkish is beneficial to the improvement of their main language skills (speaking, reading and writing) and to grammar and vocabulary. The last conclusion obtained from the study is that reading in Turkish causes positive perceptions and attitudes towards EFL learning and enhances motivation and self-confidence. As a final note, the questionnaire used in the study is appropriate for examining the contributions of recreational reading in L1 to EFL learning. In other words, it can be stated that the instrument used for the current study can be adapted to investigate the effects of recreational reading in the native language on a foreign language learning process.

Below is a summary of the results. As limited research appeared on this issue, the results of the present study contribute to the relevant literature regarding EFL readers’ perceptions of recreational reading in L1. In other words, while Cevellos (2008) found that reading in L1 created competence in a foreign language and that there existed transfer across native and foreign languages, the results of the current study showed that it has considerable positive effects on the EFL learning process. That is, in the present study, it was found that recreational reading in L1 has positive effects on improving EFL readers’ memory, intelligence, imagination, critical and creative thinking skills, research, analysis and synthesis skills, speaking, reading and writing, grammar and vocabulary, and enhances motivation and self-confidence. Another significant contribution to the related literature is that the results reflect the effects of recreational reading in Turkish as a native language on EFL learning. Limited studies focused on strategy use in Turkish as a native language and EFL reading (Oncu, 1998), culture effects on foreign language literacy, motivational issues (Tercanlioglu, 2001), and the feasibility of transference between the native and foreign languages regarding reading strategies. Given that no study was conducted on the issue with regard to Turkish as a native language, the results of the current study are significant in terms of describing the effects of reading in Turkish on the EFL learning process in an EFL context in Turkey.

Given that recreational reading in the native language has considerable positive effects on EFL learning, some practical recommendations can be made. First, the questionnaire designed, tested, and analyzed in this study can be used to evaluate perceptions of EFL learners towards recreational reading in the native language. Second, recreational reading in the native language is beneficial for improving memory, intelligence, imagination, critical and creative thinking skills as well as research, analysis and synthesis skills. Third, EFL learners can read in their native languages to increase their awareness of the differences and similarities between native and foreign languages, their awareness of the changes and development of languages and the development of their speaking, reading and writing, grammar, and vocabulary in their target language. Last, EFL teachers should encourage their students to read books to enhance motivation and self-confidence. It can be emphasized that foreign language teachers should encourage and motivate their students to read books in their native languages, as recreational reading is a very useful tool to improve the cognitive and linguistic skills of EFL learners and to create positive perceptions and attitudes towards foreign language learning.

As a final note, there were three limitations of the study. First, the participants in this descriptive research were restricted to 261 students studying in the ELT department of Balikesir University, Turkey. Second, the scope of the study was confined to the descriptive data obtained from the questionnaire designed in accordance with the qualitative data. Finally, further studies should focus on the relationships between EFL learners’ perceptions of recreational reading and some independent variables such as demographic factors, reading amount and frequency.

Ageletti, N., Hall, C. & Warmac, E. (1996). Improving Elementary students’ attitudes toward recreational reading. Master of Arts Research Project, Saint Xavier University and SkyLight Professional Development.

Aydin, S. (2003). The feasibility of transference between native language and foreign language regarding reading strategies. MA Thesis, Marmara University, Turkey.

Bray, E. (2002). Using task journal with independent readers. Forum, 40(6), 6-11.

Burnett, C. & Myers, J. (2002). “Beyond the frame”: Exploring children’s literary practices. Reading: Literacy & Language, 36(2), 56-62.

Buschick, M. E., Shipton, T. A., Winner, L. M. & Wise, M. D. (2007). Increasing reading motivation in elementary and middle school students through the use of multiple intelligences. An Action Research Project Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Education at Saint Xavier University.

Cevellos, T. (2008). My journey as a reader. Knowledge Quest, 36(3), 64-65.

Chang, J. S. & Krashen, S. (1997). The effects of free reading on language and academic development: A natural experiment. Mosaic, 4(4), 15-15.

Cho, K. & Krashen, S. (2001). Sustained silent reading experiences among Korean teachers of English as a foreign language: The effect of a single exposure to interesting, comprehensible reading. Reading Improvement, 38(4), 170-174.

Constantino, R. (1995a). Learning to read in a second language doesn’t have to hurt: The effects of pleasure reading. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 39(1), 68-69.

Constantino, R. (1995b). The effects of pleasure reading. Mosaic, 3(1), 15-17.

Corridon, L. B. (1994). Improving third-grade students’ attitudes to reading through the use of recreational reading activities. Dissertation, Nova University. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED369043).

Crandall, J., Jaramillo, A., Olsen, L & Peyton, J. K. (2002). Using cognitive strategies to develop English language and literacy. Eric Digests, 2002-10, 1-7.

Greenberg, D. Rodrigo, V., Berry, A., Brinck, T., & Joseph, H. (2006). Implementation of an extensive reading program with adult learners. Adult Basic Education: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Adult Literacy Educational Planning, 16(2), 81-97.

Gunter, J. C. (1994). Motivating first-grade students to read independently for pleasure through a whole language program. Nova Southeastern University. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED384857).

Holden, J. (2004). Creative Reading. London: Demos.

Hsueh-Chao, M. & Nation, P. (2000). Unknown vocabulary density and reading comprehension. Reading in Foreign Language, 13(1), 403-430.

Krashen, S. (1997). Does free voluntary reading lead to academic language? Journal of Intensive English Studies, 11(1), 1-18.

Kurtul, H. (1999). The role and importance of culture and L1 reading skills in foreign language literacy. MA Thesis, Canakkale 18 Mart University.

McCarthy, S., Nicastro, J., Spiros, I & Staley, K. (2001). Increasing recreational reading through the use of read-alouds. Master of Arts Research Project, Saint Xavier University and SkyLight Professional Development.

Oncu, O. (1998). A descriptive analysis of strategy use in L1 and L2 reading by Turkish EFL learners. MA Thesis, Anadolu University, Turkey.

Pichette, F. (2005). Time spent reading and reading comprehension in second language learning. Canadian Modern Language Review, 62(2), 243-262.

Powling, C., Gavin, J., Pullman, P., Fine, A. & Ashley, B. (2003). Meetings with the Minister: Five children's authors on the National Literacy Strategy. Reading: The National Centre for Language and Literacy.

Raemer, A. (1996). Literature review: Extensive reading in the EFL classroom. English Teachers’ Journal, 49, 29-31.

Sainsbury, M. & Schagen, I. (2004). Attitudes to reading at ages nine and eleven. Journal of Research in Reading, 27, 373-386.

Tercanlioglu, L. (2001). The nature of Turkish students’ motivation for reading and its relation to their reading frequency. Reading Matrix: An International Online Journal, 1(2).

Wu, S. (2000). Journal writing in university pleasure reading activities. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED463650)

Yang, A. (2001). Reading and non-academic learners: A mystery solved. System, 29(4), 451-466.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English for Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|