A New Model for General English Textbooks’ Design: Inviting Philosophy to the Scene!

Mohammad Amerian, Iran

Mohammad Amerian holds B.A. in English Language and Literature and M.A. in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) from Semnan University, Iran. He has taught English in various levels and currently is a university lecturer. Amerian’s research interests center around Psycholinguistics, Social Psychology, Semiotics, Language and Socio-Cultural Studies, and Pragmatics. He has also participated in several (inter)national conferences with interdisciplinary presentations. e-mail: mamra2006@yahoo.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Background

The ‘fashionable’ taste!

The tentative model

Conclusion

References

This paper tries to introduce and elaborate on a new content model for the General English textbooks’ design. In general, it is seen that in syllabus design and material preparation, some challenging topics have been ignored altogether because it was thought that they will encompass deviations from the educational syllabus or even endanger the students’ ideologies or beliefs. Philosophical and epistemological issues are among such kinds of subjects. Although existing all over the world, this is mainly seen in the countries in which religious and cultural traditions are mostly valued and emphasized. The proposed model in this article is based on the actual observational needs-analysis by the researcher and has taken different fields of study (as History, Philosophy, Cosmology and Epistemology) into account through a gradual procedure. The model asserts that if regulated well; challenging topics will not deviate the learners, but in fact, stimulate their wisdom and flourish their judgment and outlook. In brief, they will open new horizons for the intellectual development of learners while they are engaged with language learning.

One of the key issues in language learning and teaching is syllabus design and curriculum development. There exist a number of different definitions for syllabus design. Graves (1996) defines syllabus as “the specification and ordering of content of a course or courses” and for him, curriculum is “the philosophy, purposes, design, and implementation of a whole program”. For White (1988), ‘syllabus’ can be easily referred to the content or subject matter of an individual subject. Dubin and Olshtain (1997) proposed that a syllabus is a more detailed and operational statement of teaching and learning elements which translates the philosophy of the curriculum into a series of planned steps leading towards more narrowly defined objectives at each level. But, in addition to these simple statements, there are definitions that pay more attention to the socio-constructive nature a syllabus may have. For Candlin (1984), syllabus is a social construction produced interdependently by teachers and learners concerning the specification and planning of what is to be learned. Hadley (1998) put steps further and held that a syllabus is an endorsement of a specific set of sociolinguistic and philosophical beliefs regarding power, education, and cognition … that guides a teacher to structure his or her class in a particular way. Syllabus designing shapes the general framework of any educational course and is not only theoretically responsible for the content and materials of the course, but also for the outcome and practical considerations.

Regarding the syllabus, some classifications are suggested by scholars who focused on aspects of the term. White (1988) classified syllabi to Interventionist (what should be learned) and Non-interventionist (how the language is learned and integrated with learners’ experiences). Long and Robinson (1998) Discussed about the ‘Synthetic’ syllabi (which present L2 in a course of gradual accumulation of separately taught parts, and rely on the learner’s ability to combine the pieces accurately) and ‘Analytic’ syllabi (that present L2 in a process of natural sets of chunks without linguistic control and rely on the learner's competence to use the language appropriately). The distinguishing border between product-oriented and process-oriented syllabi is pioneered by Nunan (2000) in which the first concept focuses on ‘knowledge’ and the second; on ‘learning experiences’. Following the dichotomy, Rabbini (2002) correspondingly emphasized the ultimate specified goal for product-orientation of language learning and its flowing process for the process-oriented look.

Syllabus design and materials preparation gives teacher a general and at the same time specific scheme for the education. As Nunan (2000, p. ix) stated, this general scheme “can be divided at least to three main critical branches: language knowledge with its conventional levels of linguistic description (skills and components), modes of behavior as the realization of the knowledge, and modes of action as a practical and applied rendering”.

If we want to come at the body of any language learning syllabus such as functions and situations, tasks activities, language forms and communicative needs, various components can be pointed to. One specific and vitally important area with regard to the content of any syllabus is the realm of Notions; “the meanings a learner needs to express through language” (Richards & Schmidt, 2002, p. 365).

If language teaching aims to be genuinely professional and up-date, it seriously needs regular diagnosis, experimentation, evaluation and interpretation. In other words, the syllabus which is in harmony with the needs of the learners, which does consider the persuasive forces and drives within the learners, and which really cares motivation, must be a pre-planned but not a constantly-fixed one.

Imagine common books in language pedagogy as Interchange, Headway, American English file et al.. As can be seen, most of (in fact, all of!) what we have seen as syllabi for general English learning courses have been consisted of regular trends, routine patterns and repetitive frameworks. They introduce a series of forms, functions and situations and represent their corresponding materials within. Yes, this didn’t happen at once. There exists a considerable body of research, practice and theorization a part of which are the outcomes like dividing syllabi based on their nature and function and describing them as tangible labels such as Structural/Grammatical, Functional/Notional, Synthetic/Analytic, etc..

There is a long history of interchanging ideologies and replacement of syllabus modes. But for the purpose of improving the educational system in terms of curriculum development and material Preparation, we need to do more. By having a glance at the regular general English books, we can see a variety of ideas, functions, communicative situations, and subjects raised and developed during the whole book. Friends and Family, Food, Weather, Transportation, City, Marriage, Nature and Landscape, Health and Sanitation, Sports, Popular Culture and so many other interesting issues are presented in the books with nuts-and-bolts of grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation (at the service of each other). This “popular themes-based/popular topics-based” system has really changed the condition from the age of merely syntactic and painfully structural patterns. In fact, the semi-revolution really helped many generations. But it seems that some other topics (somehow with a different nature) can be added to flourish the learning process. Those ideological topics which are suitable to be included in general English books can serve so many functions and if regulated well, can be so much fruitful.

This paper tries to introduce a new model for general English textbooks’ design by inviting these ideological topics -which have always been criticized and accused of being irrelevant and even; destructive. Certainly, the idea of ‘Critical Thinking’ is of much relevance to the ultimate goal. Having discussed about the increasing attention to critical thinking in English language teaching, Pishghadam (2008) spoke about the recent emergence of various educational materials which focus on topics like ‘justice’, ‘ideology’ and ‘politics’ in language classes. He added that “proposition of critical theories by philosophers resulted to the tendency of teaching experts to critical thinking to the level that Piaget regards persons with high levels of critical thinking as the main goal of education in each country”.

This paper argues that challenging topics will not deviate the learners, but in fact, stimulate their wisdom and flourish their judgment and outlook. In brief, they will open new horizons for the intellectual development of learners while they are engaged with language learning.

Usher and Edwards (1994) believed that Education must become the vehicle for the celebration of diversity, a space for different voices against the authoritative one. It may come true that embedding new (but certainly “evaluated”) horizons to language pedagogy will lead to more effective teaching.

This article seeks if our regular and cliché-type syllabus design principles and presuppositions can be changed in some way. Having reviewed the literature, we can claim that almost nobody has dealt with this critical issue, especially in its ‘ideological’ form. In fact, throughout the bulky atmosphere of literature on topics such as syllabus design, materials preparation, or curriculum development, at most, do exist reports in form of book, article, or project which have targeted the re-analysis of the syllabus design guidelines and parameters regarding the general ‘process-oriented’ -if not just ‘circular’- considerations (the writer’s googling on combination of syllabus design + curriculum development + English teaching and learning + philosophy had 288/000 resulted in no connection to the intended goal. As can be guessed, they were just about the ‘philosophy under language teaching/learning’). The reason behind can be the truth that the major attempt throughout the literature has been the move on from the scholastic-typed programs and syllabus charts (structural, grammatical, etc.) to more dynamic, engaging, and fluid educational streams –or simply put; changing product to process.

It seems predictable that according to most of our colleagues and TEFL fellows, the idea of embedding ‘Philosophy’ into language learning and teaching is not defined yet and its validity is under question. This unconsciousness, non-acceptance or even rejection is totally disputed by the underlying supposition of the present article.

As mentioned, the two main reasons of such kind of resistance are educational and moral. They can be that:

- Most of us, English practitioners, think that philosophical topics are totally unrelated to educational goal-settings and principles. Hence, are keeping ‘food-cloth-hobby’ fashion in the main circle of syllabus design and wholly deny the educational (Human-making!) value of challenging topics as those in Philosophy.

- These challenging topics are kept intact due to the supposition that they are religiously or morally critical, if not dangerous! Actually, it is mostly believed that including philosophical topics will not only be value-less here, but can endanger the students’ ideologies and beliefs.

This article has persuasive and even satisfactory responses to both of the raised issues and will invite teachers to include challenging themes and subjects during their educational setting.

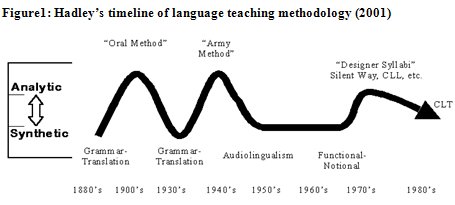

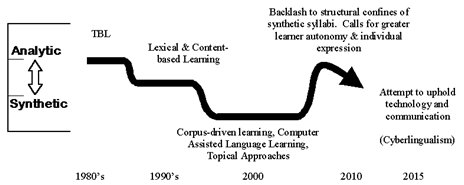

Although all its contents can be seen as waves of a spectrum and not as separated blocks, the history of syllabus design and curriculum development is in line with changes in the history of language teaching methodology (itself borrowed from linguistic and psychological movements). In the late 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, during the Faculty/scholastic phase, there was an intense force on learning writing and appreciating literature, composed of ‘mastery’ over grammar, translation, and essay-writing. The next phase (1930-1950) was the age of emphasizing structural patterns followed by embracing the ‘practice’ of aural/oral skills in order to ‘overlearn’.

The cognitive era transformed the atmosphere to more ‘mentalist’ considerations engaging the cognitive and meta-cognitive trends to optimize the efficiency of learning. The next decades (1970s and 1980s) saw ‘functional’ individual-based moves which not only valued mind, but also taste and feeling. This was in harmony with the introduction of Communicative Competence (CC) by Dell Hymes (1972) which revolutionized the syllabi including that from then on, communicative needs were tried to be met, more (the story continues to the modernistic and post-modernistic reviews with counterparts as ‘eclectic’ and ‘No-method’ talks!). Hadley (2001) described this ‘long and winding road’ with a try to forecast the future trends.

All mentioned ages have had their syllabus-related off-springs, of which the major paradigms contained a shift from product-orientation (with static and structural patterns) to process-orientation (with dynamic and non-linear frameworks). Our present situation in syllabus design is rooted in the so called Communicative era. When coming to recognize ‘notions’ and ‘functions’, we see that a lengthy list of general communicative themes and topics have been developed which helped the learners in their language use in real settings. Titles such as ‘food’, ‘clothing’, ‘weather’, ‘sports’, ‘cinema’ and ‘vacation’, and functions such as ‘introducing yourself’, ‘greetings’, ‘in a restaurant’, ‘asking price’ and ‘asking addresses’ are actual manifestations of this communicative look which is undoubtedly necessary but not enough! They are essential in guiding the learners in their personal expressions, social interactions and total engagement, but we must beware not to change them into a ‘fashion’ and think that all is That! This article asserts that for two reasons, adding (and not; substituting) some challenging topics to the taste is required:

- All human beings are full of important queries and serious questions regarding the radical epistemological issues. Educational settings have the potential and convenient atmosphere to answer the thirst based on intellectual atmosphere, mutual respect, and inherent reasoning beneath. In fact, the model doesn’t abandon the ‘Needs Analysis’ of the learners, at all, but tries to put that if intellectual needs be embedded when students are supposed to learn the language, they will be intellectually pushed forward and this leads to optimum and efficient learning.

- Dealing with such kinds of issues is not tiring or disgusting for the students, and if regulated well, can highly stimulate their interest and motivation even for learning their compulsory stuffs.

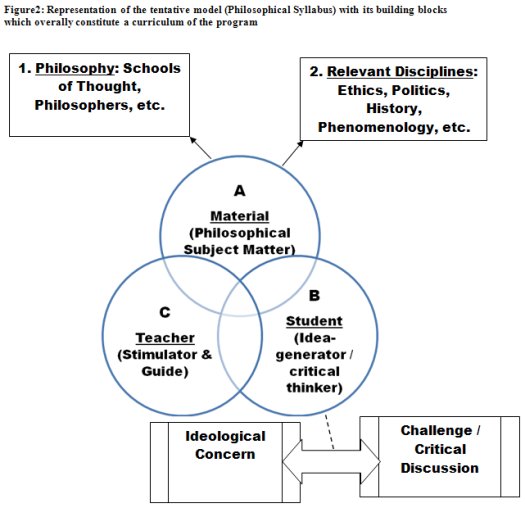

Like any framework, the tentative model going to be suggested by this paper needs careful regulation and adjustment.

Firehammer (2007) talked about a reaction to the assumed certainty of scientific or objective efforts to explain the reality. After the modernistic revolution, in all of the disciplines, this questioning stream is highly skeptical of the explanations which claimed to be valid for all groups, cultures, traditions, or races, and instead; focuses on the relative truths of each person. Education is not a separated area; nor is it far from the existing and changing atmosphere as in the postmodern age. It affects and is affected. For Beck (1993), postmodernism in education is a paradigm that challenges how we learn and appreciate knowledge in our lives. It questions the idea of a universal unchanging unified self or subject which has full knowledge of and control over what it thinks, says and does.

The model presented in the article is -to extents- of a postmodern nature. According to Breen (1999), the pedagogy of the language classroom should deal with questioning absolutes, welcoming ambiguities, accepting uncertainties, participation in different and new discourses and exploring other identities. The main goal of the suggested model is to include Philosophy and philosophical topics in English language teaching. The writer strongly believes that such embedding would not only does not do any harm to the syllabus, but also refresh the cliché-type framework by engaging the serious ideological concerns of the learners, hence; naturally motivate them to both seek their answers and learn the language lesson.

By the umbrella term ‘Philosophical Issues’, here we mean all those themes, topics, subject areas and fields which deal with our serious ideological concerns. By implementing such a view, certainly, terms like ‘Cosmology’, ‘History’, ‘Epistemology’, ‘Existentialism’ and ‘Ontology’ are in the ground. In fact, in addition to the educational targets indicated, the underlying goal is to if not answer some serious intellectual questions, at least creating the needed concern and stimulating the potential wisdom in relation to addressing them in the main thematic syllabus of the language teaching.

Surely, before coming at such a plan, there are many things to be considered. Here are some:

- First is the suitability of this inclusion and whether it is a deviation from the educational goals defined.

• Concerning that, the writer believes that including philosophical topics can not -by any means- be considered as ‘deviation’ from the syllabus because these topics, as those communicatives presented now are of concern to students; if not more important for them. So, they can even ‘guide’ and ‘direct’ the students’ thoughts.

- Second is the appropriateness of challenging issues for learners at all levels.

• Well, it is quite clear that the mental ability and/or interest of the learners can differ greatly. They may not be intellectually; homogeneous. The main concern of the writer was to introduce/maneuver on such topics in relation to upper-intermediate and advanced learners in terms of English proficiency. But in relation to age, simplified materials for the beginners or even children can be used. Titles such as ‘Philosophy in Simple Language’, ‘Philosophy for the Beginners’ or ‘Philosophy for Children’ have been among the best sellers. They introduce philosophical topics in a user-friendly, lovely and cute manner which attracts the immature readers. Selection, gradation and modification of appropriate materials from these sources can help the teacher much if s/he intends to apply the model for the low-level learners.

- Third is the appropriateness of including all philosophical topics in language teaching syllabus.

• There is no need (neither is it possible, valuable and advantageous) to include all topics and subjects discussed in philosophy, even in their simplified versions. To tell the truth, it actually damages the whole building! What is tried to introduce is just a balanced ‘sipping’ of the area which creates interest in the students and answers some of their concerns, as well.

Structural Organization

As far as the ‘label’ is concerned, the model proposed by this article goes under the ‘content’ syllabus but the content is not ‘communicative’ in its fashionable meaning. In fact, to reinvent a wheel, it can add ‘challenging’ syllabus, to the literature, theoretically. The usual process of selection and gradation of the materials is done in this syllabus, too. The content is best tuned if it is arranged according to the simplicity and harmonized based on the shared features (In another word, whether some topics go under one title, hypothetically). Richards and Renandya (2002) classified the curriculum development models to ‘Classical Humanism’ (structural/grammatical), ‘Reconstructionism’ (notional/functional) and ‘Progressivism’ (process/procedural). The proposed model in this paper goes somewhere between the Reconstructionism and Progressivism and values both ‘objective’ and ‘process’.

Content

Probably, the central issue concerning the syllabus design is the problem of choosing the appropriate subject matter. This article questions if Philosophy is a good one! The Encyclopedia Britannica (2012) defines ‘Philosophy’ as “the critical examination of the grounds for fundamental beliefs and an analysis of the basic concepts employed in the expression of such beliefs”. Since the aim is to critically introduce learners with some fundamental approaches to beliefs, the main building blocks of the recommended syllabus content is made up of issues directly related to Philosophy. They can include History, Schools of Thought, Religion, Metaphysics, Philosophy of Language, Philosophy of Mind, Existentialism, Idealism, Skepticism, Phenomenology, Law, Politics, Ethics, Arts and Aesthetics and so forth.

It’s noteworthy to mention that this doesn’t mean that a whole unit of a lesson be dedicated to e.g. Western Philosophy. These are the themes and motifs. The actual unit of teaching can be materials and discussions beginning about preliminary philosophical questions. The main body can be attributed to analysis of the history of human thought: major schools of thought with their representative thinkers and philosophers. The content can be arranged from Greek Philosophy, moving across the Hellenistic and Medieval and finally entering the Modern age.

As mentioned, the content should be simplified (lexically and grammatically) and made user-friendly based on the level of the intended students. The learners should at the same time comprehend the texts and see questions raised from within, based on those comprehensions which are themselves based on getting familiar with stimulating concepts, notions and problematic areas. To give a clear picture of how this syllabus looks like, table below is presented including different parts and their sequence divided according to units (the table is set for an imaginary 20-session course. It can, surely, be limited or expanded according to the necessities of the class, with careful regulation).

Table: General framework for the syllabus

| Part A |

Preliminary Concepts |

Main Question |

| Unit 1 |

Existence |

- What is the nature and qualities of the Existence? |

| Unit 2 |

God | - Is there a creator?

- What is his essence and characteristics? |

| Unit 3 | Nature | - How is the relation of human with nature? How does nature affect our life? |

| Unit 4 | Determinism/Free Will | - Are we doomed to be puppets or we have choice, ourselves? How is the extent of our free will? |

| Unit 5 | Religion | - What is Religion?

- Is it necessary to follow a religion? |

| Part B |

| Philosophical Thought | Main Question |

| Major Figures | Schools |

| Unit 6 | Socrates | Socratic Age | - Can we avoid the dangers of relativism, which seems to undermine morality and make the pursuit of truth impossible? |

| Unit 7 | Plato | Platonic Age | - Mustn’t we be committed to some more eternal and unchanging ideals if we are going to be committed to goodness and truth? |

| Unit 8 | Aristotle | Peripatetics | - Can’t we get a clear grip on knowledge and goodness, without being committed to some unrealistic ideals which we can’t experience? |

| Unit 9 | John Locke & David Hume | Empiricism | - Given that sense experience is our only source of knowledge, how far can knowledge extend, and what are the inevitable limitations? |

| Unit 10 | René Descartes & Immanuel Kant | Rationalism & Epistemology | - Given that reason is our only reliable source of knowledge, what can we deduce about reality from pure thought, and how far can we trust the appearances of sense experience? |

| Unit 11 | Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, & Jean-Paul Sartre | Existentialism | - If we accept our feeling of mental freedom as being true, how should we exercise this responsibility in our lives? |

| Unit 12 | Jacques Derrida | Post-Modernism | - What follows from the fact that relativism is right, and truth and morality change continually with culture and prejudice? |

| Unit 13 | Confucius, Laozi & Buddha | Eastern Philosophy: Chinese & Indian/ (Daoism, Buddhism) | - How is the quality of God, Creation of the world, and Life?

- How can we escape from the sufferings of life and from the endless reincarnation caused by human desires? |

| Unit 14 | Al-Farabi, Avicenna, Mulla-Sadra, | Islamic Philosophy | - Can we search for Hikma (wisdom) and save ourselves?

- How can Kalām (Islamic theology through Dialectic) help us? |

| Part C | Relevant Trends | Main Question / Problem |

| Discipline | Major Figures |

| Unit 15 | Cosmology, Metaphysics & Ontology | Saint Thomas Aquinas | - The nature of existence and ultimate reality |

| Unit 16 | Ethics | Jeremy Bentham | - Correct actions are those that result in the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. |

| Unit 17 | Politics | Jürgen Habermas,

Karl Marx | - Is modern scientific knowledge and research, objective and value-free?

- The working class should rebel and build a communist society. |

| Unit 18 | History | Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel | - Truth is reached by a continuing dialectic, in which a concept (thesis) always gives rise to its opposite (antithesis), and the interaction between these two leads to the creation of a new concept (synthesis). |

| Unit 19 | Philosophy of Art & Aesthetics | Walter Benjamin & Jean François Lyotard | - Essence and perception of beauty and ugliness, and whether such qualities are objectively present in the things they appear to qualify, or whether they exist only in the mind of the individual. |

| Unit 20 | Phenomenology | Martin Heidegger | - The structures of experience as they present themselves to consciousness, without recourse to theory, deduction, or assumptions from other disciplines such as the natural sciences |

As can be seen, the whole content syllabus is divided to three parts starting from stimulating sparkles about nature and existence (Preliminary Concepts), moving through the following reasonings (namely, Philosophical Thought), and finally proposing some special disciplines resulted from Philosophy (Relevant Trends). This content can be taught in one, two or even three semesters according to the level of the students.

At first, any TEFL practitioner may wonder if we are intending English for Specific Purposes (ESP) curriculum, actually, now in the realm of Philosophy. But this is not true, because in ESP course, the major goal is teaching that intended non-linguistic subject matter (Physics, Mathematics, etc.) through the medium of language and familiarity with the jargon and technical terms (words, expressions, and even structural patterns) but this is not so, here. When we propose this philosophical syllabus, the main aim is to teach language to the students but the subject matter is at service of Philosophy (because of the belief that this branch of science is a radical one and acts completely different from technical and academic disciplines. Hence, is highly stimulating for critical look, idea-generation and theoretical disputes).

Perhaps the Needs Analysis (NA) background of the model is best described by referring to Brindley (1989, p. 64) who postulated that there are two orientations regarding the needs-analysis: a narrow ‘product-oriented’ view and a broad ‘process-oriented’ one. The process-oriented view of needs take into account factors such as learner motivation, the one which our model seeks.

Parallel activities

As far as the challenging issues and implementing a critical look are concerned, having a structured material even with numerous eye-catching topics is not enough! There is a crucial need for discussion and challenge in the classroom so that the theoretical concerns are practically put into the practice of debate. In such a curriculum, what Prabhu (1987) entitled ‘procedural’ syllabus, Breen (1987) named ‘process’ syllabus, and Crookes (1992) labeled ‘task-based language teaching’ are so helpful if added to the aforementioned philosophical/ideological seasonings. Long and Crookes (1992) hold that central to the procedure syllabus is the belief that knowledge of linguistic structure develops largely subconsciously through the opinion of some internal system of abstract rules and principles on the bases of extensive input from the target language. This comes about when the focus is on the meaning, and the condition is best met when trying to complete the tasks.

Moreover, the teacher has an important role. Pishghadam (2008) proposed some suggestions to teachers for growth and development of critical thinking in language class and having really ‘critical’ thinkers. Below are some:

- Letting students express their attitudes, freely

- Not trying to ‘impose’ any idea in class

- Making learners question themselves

- Guiding them in how to reach a valid question and pursue its answer

- Creating a low-anxiety and enjoying atmosphere

In addition to these guidelines, teachers can make students question different subjects and phenomena. They should abandon the cliché of ‘description’ for ‘explanation’. Arriving at definite clear-cut answers is not the goal at all, but questioning existence, quality and several aspects of actions and reactions have great importance.

The inclusion of non-linguistic objectives in language learning syllabus is not a new or unknown issue. Richards (2001) emphasized on ‘non-language’ outcomes of language learning class, which include affect cultivation (such as confidence, motivation, and interest), learning strategies, thinking skills, interpersonal skills, and cultural understanding. The underlying assumption of this trend in syllabus design is that as a school subject, language education should not merely aim at helping students learn language knowledge and skills. Rather, it has responsibility of fostering students’ whole-person development.

Usher and Edwards (1996) proposed that education is ambiguous. It both seeks and rejects closure. It is both closed and open. It can be an instrument/a device for control and legitimization, but also it has the potentiality to question the status of the definitive, the certain and the ‘proven’. Pishghadam (2008) asserted that for experts, critical thinking is one of the most important educational principles in each country and that every society needs critical thinkers to grow and flourish. This fact can best be achieved through having a -this time- ‘major’ look at the Philosophy in our General English classes probably because the general root of critical theories can be found in philosophers’ thought (Rasmussen, 1996).

In addition to ‘inviting Philosophy to the scene’, the nature of what the presented model recommends has considerable looks on terms as Process-orientation, Nonlinearity, Educational Ecosystem, Dynamics, and Fuzziness. It is believed that triggering the basic beliefs and concerns and attending to fundamental ideologies will naturally increase the intrinsic motivation of the students. This curiosity-raising is, here, experimented in the English teaching context and mainly, in the lights of syllabus design and curriculum development. The model embraces Philosophy and holds that related subject matters can open new horizons for the intellectual development of learners while they are engaged with language learning. It should be said that the main educational/ideational intentions are to shape a kind of creative thinking style, inviting students to think about the issues -in addition to their usual language-related practices-, and helping them move toward a more self-centered and responsive individuality.

Slattery (2006) emphasized that the postmodern curriculum should promote a creative search for deeper understanding through interdisciplinary and inclusive tasks, projects and narratives and that its content should problematize, interrogate, contextualize, and challenge the learners. The Philosophical syllabus suggested in this article tries to be in harmony those objectives.

Beck, C. (1993). Postmodernism, Pedagogy, and Philosophy of Education. Retrieved on June 9, 2012, from www.ed.uiuc.edu/eps/PES-Yearbook/93_docs/BECK.HTM

Breen, M. (1999). Teaching Language in the Postmodern Classroom. Barcelona English Language and Literature Studies (BELLS), 10: 47-64.

Brindley, G. P. (1989). General-Purpose Language Teaching: A variable focus approach. In C. J. Brumfit (Ed.). ELT Documents No. 118. London: Pregamon Press & The British Council. 61-74.

Candlin, C. N. (1984). Syllabus Design as a Critical Process. In C. J. Brumfit (Ed.). General English Syllabus Design. ELT Documents No. 118. London: Pergamon Press & The British Council. 29-46.

Dubin, F. and Olshtain, E. (1997). Course Design: Developing Programs and Materials for Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Firehammer, R. (2007). “Postmodernism”. Retrieved from

www.spaceandmotion.com/Philosophy-Postmodernism.htm

Graves, K. (Ed.). (1996). Teachers as Course Developers. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hadley, G. (2001). Looking Back and Looking Ahead: A Forecast for the Early 21st Century. The Language Teacher, 25, 7: 18-22. Retrieved on June 12, 2012, from http://nuis.ac.jp/~hadley/publication/21centforcst/forecast.htm

Long, M. and Crookes, G. (1992). Three Approaches to Task-Based Syllabus Design. TESOL Quarterly, 26, 27-56.

Long, M. H. and Robinson, P. (1998). Focus on form: Theory, Research and Practice. In Doughty, C. J. and Williams, J. (Eds.), Focus on Form in Second Language Acquisition (pp. 15-41). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunan, D. (2000). Syllabus Design. UK: Oxford University Press (OUP).

‘Philosophy’. (2012). Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

‘The Major Schools of Philosophical Thought’. Retrieved on July 11, 2012 from www.philosophyideas.com/files/intro/Schools of Philosophy.pdf

Pishghadam, R. (2008). افزایش تفکّر انتقادی از طریق مباحثة ادبی در کلاس های زبان انگلیسی [Enhancing Critical Thinking Though Literary Discussion in English Language Classes]. Majale-ye Daneshkade-ye Adabiat va Olum-e Ensani-e Mashhad, 159: 153-170.

Rabbini, R. (2002). An Introduction to Syllabus Design and Evaluation. The Internet TESL Journal, 8(5). Retrieved on May 8, 2012, from http://iteslj.org/Articles/Rabbini-Syllabus.html

Rasmussen, D. M. (1996). Critical Theory and Philosophy. In Rasmussen, D. A., Editor, The handbook of critical theory, Oxford: Blackwell, 17-38.

Richards, J. C. (2001). Curriculum Development in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (CUP).

Richards, J. C. and Schmidt, R. (2002). Longman Dictionary of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics. UK: Longman.

Richards, J. C. and Renandya, W. A. (2002). Methodology in Language Teaching: An Anthology of Current Practice. UK: Cambridge University Press (CUP).

Slattery, P. (2006). Curriculum Development in the Postmodern Era. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis.

Usher, R. and Edwards, R. (1994). Postmodernism and Education. Routledge, London.

White, R. (1988). The ELT Curriculum, Design, Innovation and Management. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|