Learning Through Tests: Does Testing Improve English Language Learning?

Müjgan Büyüktaş Kara, Turkey

Müjgan Büyüktaş Kara graduated from the Western Languages and Literatures Department at Bogazici University in Istanbul, Turkey. Following graduation she began working as a Research Assistant in the English Language Teaching Department at Istanbul Aydin University. She started her MA in English Language and Literature at the same university. Her MA thesis was “CBI (Content-Based Instruction) for Literature Students’ Proficiency Development.” She received her CELTA from Oxford House College in London, UK, and her TEFL International TESOL Certificate from Tuscany Learning Centre in Florence, Italy. She also began the DELTA Module I at ITI, Istanbul. She is currently working as an English Language Instructor at Bahcesehir University English Preparatory School in Istanbul, as well as working on her PhD Proposal, “Processing ‘Process Writing’ for Turkish Students: Detecting the Problems and Finding the Solutions.”

E-mail: mujgan.buyuktaskara@bahcesehir.edu.tr

Menu

Introduction

Abstract

Literary survey

The research

The aim

Objectives

Research questions

Research approach

The subjects

The research method

The outcomes

The conclusions

The research result

Suggestions for further researches

References

Testing and assessment is an important phase in foreign language teaching and is usually regarded as the last step of the learning process, the point where instruction stops and the student’s learning until that point is evaluated. In the English Preparatory School of private universities, administration can even organize the classes by gathering the more successful students into “super classes,” or by placing them among their peers in “repeat” classes which are thought to be more suitable for their language level. The student’s level is determined by tests prepared by the university’s testing office.

There are many advantages and disadvantages to this kind of a system, but we should also ask ourselves whether testing and assessment should be an integral part of the language learning process. A beneficial way is to analyse the outcome of a certain exam and determine the needs of the individual student, the classes, the teachers and the testing office. This is a complete system to be implemented over time and will most likely greatly alter the quality of education within the institution.

An alternative route is to raise the student’s awareness of the language. Many students are unaware of the importance of this process. They are accustomed to being spoon-fed their education and are far from being able to learn autonomously and determine their own needs.

We often observe a rise in student awareness after the first exam. If we talk about the vocabulary, for example, we see that during a class most students are uninterested in the new words covered in each lesson. Alternatively, following an exam, simply because they had to deal with words in an environment without a dictionary, their curiosity seems to be excited about the questions they are asked – even if they answer the question incorrectly, they usually want to learn the right answer.

Confronting words in a test environment raises the “importance” of the new word. The student’s mental occupation with the word over a certain period creates an awareness and curiosity towards that word. Students usually remember the new words that they are tested on. It contributes to the importance and effectiveness of the lesson once the test is over and makes the lesson much more important for them.

However, since it is not often possible to test the students on the same words, the students don’t have possibility to use the vocabulary in numerous contexts. They summon the word from their short-term memory and dispose of it before it can become deeply rooted in their long-term memory.

With the question “Does testing improve second language learning?” as a starting point, this research was conducted with two groups in two different classes with similar backgrounds. One group completed the test first before they studied the material, and the other group studied the new words before they were tested on them. Both groups later took a final retention test where the students’ knowledge of the new words was tested. The hypothesis of this research seemed to prove wrong in the first analyses. The control group who learned the words first and took the test later, using the classical approach, proved to have a more extensive understanding of the new vocabulary by performing better in the final retention test. The average score of the man group was 7, whereas the average score of the control group was 11. However, when the improvement ratios of the students’ vocabulary were contrasted between the first and the second tests, it was seen that the students in the main group had an improvement rate of 3.50, whereas the main group had an improvement rate of 2.75. Therefore, in terms of improvement rates, it can be seen that the first test of the main group has successfully increased the awareness of the students’ towards the vocabulary items and the hypothesis of this research has proved right. The question therefore is why the students in the control group, although they had a smaller improvement rate than the main group, still learned more words when we compared the final scores?

What was undermined in this research was the double testing system both in the main and the control group. Apparently, the students in the control group have also benefited from the double testing system. Therefore, it is evident that a small change in the research method can more successfully prove the hypothesis, both in terms of the final scores and the improvement rates. Therefore, further research needs to be done on the issue.

Other research covers similar approaches to testing and its effects, the most beneficial being Test-Enhanced Learning, outlined in “Taking Memory Tests Improves Long-Term Retention” by Henry L. Roediger and Jeffrey D. Karpicke, which was done in the Washington University Department of Psychology.

In this research on delayed tests, prior testing produced substantially greater retention than studying, even though repeated studying increased the students' confidence in their ability to remember the material. They reached the conclusion that testing is a powerful means of improving learning, not just assessing it.

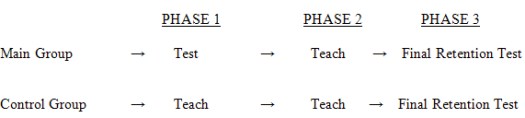

Testing and its effects on students’ acquisition of a second language is analysed in this action research. The researcher attempted to understand testing and its immediate effect on a student by challenging the classical cycle of teaching-testing and reversing the process, that is, testing-teaching. This reversed cycle was evaluated with a final retention test, conducted to both the main group and the control group. The outcomes are analysed in charts to reach a conclusion.

The aim of this research is to find out whether taking a test helps students improve their language learning. But even if the hypothesis is proved, the difficulty of implementing this kind of a system in all areas of a student’s second language learning is evident. Therefore, this research aims to challenge the classical cycle of teaching-testing only to raise awareness of the importance of testing not simply as a means of evaluation, but also as a means of revision for the students. This may help to determine whether testing improves learning a second language beyond the benefits it provides as an avenue to revisit the material. This research can be used as a starting point for further research to explore the importance of a student’s dynamics and motivations in second language learning.

Since testing is an immense field with many different principles and different skills, the research area of this research is using testing for the improvement of vocabulary retention.

Learning vocabulary is not a skill that can be acquired like other skills. Prior research has shown that students have a capacity to learn five to nine words within an efficient vocabulary lesson. The greatest command of the new words comes when students see those words in approximately seven different contexts.

On the other hand, in this research testing the students’ on the vocabulary items enabled the researcher to distinguish a student’s prior proficiency in English from their command of the recently learnt vocabulary items. In this sense, using vocabulary teaching as the research area created a fair atmosphere.

The objectives of this research are (i) to analyse whether testing can be used to help tackle vocabulary teaching, (ii) to see whether it can alter the student’s attitude toward the new vocabulary and (iii) to open up new research areas and reach a solid conclusion through further research.

- Does testing improve second language learning?

- If so, is it because of its quality as a stimulation to learn the vocabulary or because it is used as a means of revision or both?

- Can testing be used as a preliminary exercise before teaching the vocabulary?

This study attempts to use the quantitative empirical research method in the analysis of the intervention program of the experimental group. The results are shown in charts and discussed in depth.

34 A2 level students studying in the English Preparatory School of a private university in Istanbul, Turkey, ages 17 to 22, participated in partial fulfilment of teacher assessment requirements. Their grades didn’t affect their GPAs.

The students are from two different groups from two different classes. They are tested in groups of 17. Their GPAs are very close to one other in their quizzes and in the midterms conducted by the university’s testing office.

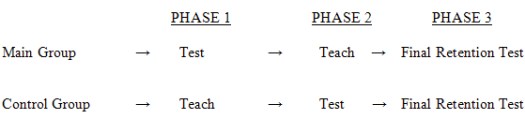

This research is conducted through simultaneous experiments with two groups of students.

PHASE 1

The main group took a vocabulary test of 20 new words. The words were given in a box and the students were asked to fill in the blanks in the sentences with the given words in the box. The sentences were easy to understand. You can find an example below:

The chemist looked at the __________________ and gave me this medicine.

(Ans: prescription)

The students filled in the blanks in 20 sentences with the 20 new words from the box.

The control group was taught the same 20 new words by their teacher. The new words were explained in context and the students didn’t know they would have a test on the new words.

PHASE 2

The main group was taught the 20 new words by their teacher the day after they took the test. The new words were explained in context. The students didn’t know that they would have a second test on the new words.

The control group took the same vocabulary test with the main group the day after they were taught the words.

PHASE 3

Both the main group and the control group took a final retention test on the same words they were tested on and taught by their teacher. The test consisted of one section where the students matched the 20 definitions with the 20 words in the box. You can find an example below.

A special paper written by a doctor, ordering medicine for someone: __________ (Ans: prescription)

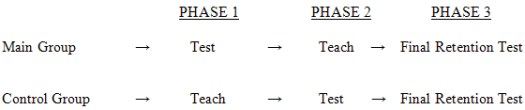

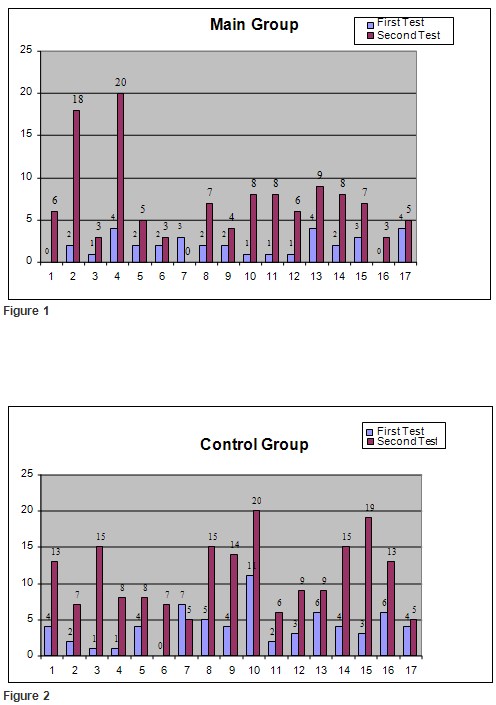

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the students’ performances in the first and second tests.

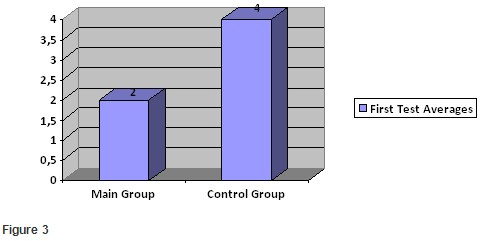

In Figure 3 below, we see that the control group performed better in the first test. This is an expected outcome considering the phases of the research, where the control group were taught the new words before they took the test, whereas the main group met the new words for the first time. Therefore, the chart below shows the expected outcomes of the first test.

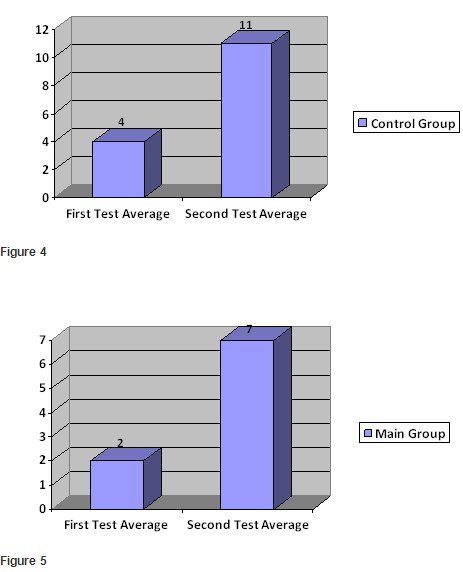

Also, in Figures 4 and 5 below, when we compare the students’ performances in the first and the second tests respectively, we see that the main group has a 3.50 improvement rate and the control group has a 2.75 improvement rate. According to these figures, it is evident that the improvement of the main group is better than that of the control group. Therefore, the hypothesis of this research has been successfully proved.

An unexpected outcome is the relatively better but still meagre performance of the control group in the first test. They had already studied the meanings of the new words, but still didn’t perform very well. This might have been because a student’s maximum vocabulary learning capacity is five to nine words a day. But it shouldn’t be ignored that the students’ performance is not in line with that capacity, either. The average success rate of the class is four words out of twenty. This leads into thinking to what extent the teaching of the vocabulary items was effective in the students’ retention of the new words.

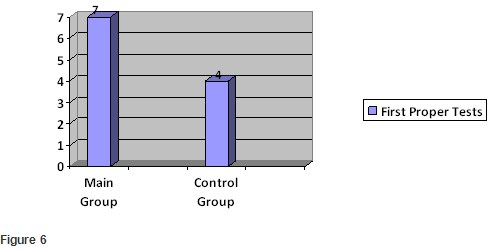

Another unexpected outcome is the score of the control group in the final retention test. The main group have a better improvement rate when their success in the first and the second tests are compared with an improvement rate of 3.50 in the main group and 2.75 in the control group. However, we see that the control group scored better than the main group in the final retention test and therefore, proved to have a more extensive understanding of the new vocabulary with an average score of 7 in the main group and 11 in the control group. Therefore, in terms of improvement rates, it can be seen that the first test of the main group has successfully increased the awareness of the students’ towards the vocabulary items and my hypothesis has proved right. The question therefore is, why the students in the control group, although they had a smaller improvement rate than the main group, learned more words than the main group? This will be discussed in the conclusions section of this research.

Although the hypothesis of this research proved right when we compare the improvement rates of the main group and the control group, the reasons for the success of the control group in the final retention test should also be examined. Let’s remember the chronology of the phases of this research before discussing these reasons.

According to the chronological order of the research process, it can be seen that the first valid test of the main group cannot be the first test in Phase one, but only the “final retention test” in Phase three. For a test to be a fair means of assessment, the students should be given the chance to study the material they will be tested on. In other words, the first test of the main group cannot be said to be a “real test” because it is not designed to test their knowledge, but rather used as an alternative means of stimulation. Therefore, it is also fair to compare the outcomes of the final retention test of the main group and the first test of the control group, both of which are the first tests of those students after they have studied the words properly.

In Figure 6, we can see that the students of the main group performed better than the students of control group in their first proper tests.

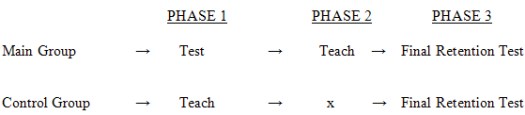

This leads us to the conclusion that the research method may need revision. The hypothesis of this research could more successfully be proved if it is redesigned and conducted as is shown below.

The factor that would lead to proving the hypothesis is a difference in method, where we omit the test in the second phase for the control group. If we start over, this means giving an extra test to the main group before they go over the same phases with the control group.

However, it can also be considered unfair to expose the students in the main group twice to the items. It may lead to an implication that the stimulation quality of the first test of the main group is undermined.

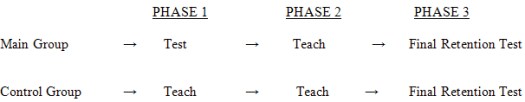

However, what was overlooked in the beginning of this research is the double testing system both in the main and the control group. Apparently, the students in the control group have also benefited from the double testing system as the students of the main group. Therefore, a more fair process can be found below.

The above process suggests that testing the main group before they study the vocabulary items, can prove to be a better stimulation than restudying the items.

Therefore, further research needs to be done on the issue considering the above changes in the research method.

The results of this research suggest that challenging the classical teaching-testing cycle leads to a student’s improvement in acquisition of vocabulary when learning a second language. It is evident that testing raises the curiosity of the students towards the vocabulary items they are tested on because of its stimulation effect.

However, further research needs to be done in order to distinguish between the two qualities of testing mentioned in this research - a means of stimulation and a means of revision, with a change in the research method as has been suggested before. Still, this research can be thought of as a reason to prompt teachers to think of the test in Phase 1 as a warm up for the target vocabulary of the next lesson. Dealing with the words a student has never encountered before will raise their curiosity towards the words and they will learn them better than students who meet these words for first time during a lesson. Therefore, testing can be used as a more effective stimulation device than simple repetitive studying.

To be able to understand the efficacy of using tests to improve a student’s foreign language skills we have to redesign our research method, which will inevitably lead us to another action research. This new research should have the same method for the main group but in Phase two the control group should study the vocabulary again instead of taking a test. This will lead us to the hypothesis: “Is testing a more effective stimulation for learners than repetitive studying, even if those tests are not graded?” The approach will be a more psychological one.

You can find the details of the process below.

Another way to reach more solid conclusions is to repeat the tests and compare the outcomes of the repeated tests taken at different intervals to see whether testing proves better than restudying the material in the long run.

Brown, J. D, (1988) Understanding Research in Second Language Learning: “A Teacher's Guide to Statistics and Research Design”. Cambridge University Press.

Costello, P. J.M, (2004) Action Research. Continuum.

Genesee, F. and J. A. Upshur, (1996) Classroom-based Evaluation in Second Language Education. Cambridge University Press.

Lightbrown, Patsy M. And Nina Spada, (2006) How Languages Are Learned. Oxford University Press.

Roediger, H. L. and J. D. Karpicke, (February 2006) Test-Enhanced Learning “Taking Memory Tests Improves Long-Term Retention”. Washington University Department of Psychology. January 2009.

www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118597351

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|