Reading Outside the EAP Classroom

Nicholas Northall, UK

Nicholas Northall works at the English Language Teaching Centre at the University of Sheffield, where he teaches EAP as well as contributing to the centre’s teacher training programme. He is interested in improving reading skills, computer assisted language learning and academic writing. E-mail: northalln@hotmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Background

Extensive Reading

Methodology

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

References

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Strong reading skills are undoubtedly one of the most important skills for any student in higher or further education. Alexander et al state that ‘reading is a core requirement at all levels of academic study and may take up the largest part of a student’s time’ (2008: 119). Jordan (1997) also points out that reading is essential and that an inability to read successfully will not result in academic success. Yet it has been observed that EAP students at the author’s place of work find reading difficult and as a consequence do not enjoy it. Furthermore, during one-to-one tutorials students have stated that they read very little in English outside of class. Finally, many of these students in the past have performed badly in the reading section of the IELTS examination (this is the International English Language Testing System, which is an internationally recognised test of English proficiency), while performing relatively well on the other sections.

The first aim of this study was therefore to find out how much EAP students read in their own time. The second aim was to introduce and evaluate a programme to address this lack of reading. It was hoped that if students were given both advice and access to reading material in the classroom, they would as a result read more in their free time. Although the students were given access to reading material, they were also encouraged to read whatever they wanted: that is, the classroom material was used to remind students to read in their own time.

This small-scale case study, observing one class of EAP students, took place at the English Language Teaching Centre (ELTC) at the University of Sheffield over a fifteen week semester. Each week the students had 20.5 hours of English language instruction, consisting of academic reading, writing and listening, IELTS examination preparation as well as separate classes for grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation work.

Nine students (4 male and 5 female) participated in this research (see Table 1 below). Five of these nine students were taking the course to prepare for a higher degree whereas the remaining four were studying at the centre to improve their general language skills. At the beginning of the course the approximate language level of all the students was 5 – 6 at IELTS. However, four of the five students hoping to take a post-graduate degree needed to obtain 6.5 at IELTS within a year of beginning their English language course. Together with a student given an unconditional offer, they also needed to gain relevant academic English skills. Therefore, all five of these students were highly motivated to study, handing in at least one piece of written homework per week. Furthermore, the attendance of these five was also well over 90 per cent. Of the four students studying to improve their language skills, two attended regularly (with over 90% attendance) and handed in written homework at least once per week. The attendance of the other two was quite haphazard, with the first lesson of the day often missed and very little written homework handed in.

Table 1: Summary of Participants (pseudonyms have been used to protect the identify of the participants)

| Name | Nationality | Reason for study | IELTS score needed |

| Abdulaziz | Saudi Arabian | MSc in Computer Science | 6.5 |

| Nasser | Libyan | MSc in Communication Engineering | 6.0 |

| Norah | Saudi Arabian | MSc in Information Management | 6.5 |

| Freedah | Saudi Arabian | >PhD in Statistics | 6.5 |

| Aisha | Saudi Arabian | PhD in Biology | Unconditional |

| Bo Leung | Chinese | Language Improvement | N/a |

| Shin | South Korean | Language Improvement | N/a |

| Pablo | Columbian | Language Improvement | N/a |

| Claudia | Columbian | Language Improvement | N/a |

This study was concerned exclusively with reading done outside of the classroom; that is in the student’s own time. This is commonly known as extensive reading, which Bamford and Day define as:

…an approach to language teaching in which learners read a lot of easy material in the new language. They choose their own reading material and read it independently of the teacher. They read for general, overall meaning, and they read for information and enjoyment. (2004: 1)

Brown (2009) elaborates believing that ‘extensive reading means that students choose what to read and it means they do most of the reading by themselves outside of class’ (p241). This kind of reading is not usually assessed, although Day and Bamford (1998a) argue that a student’s progress could be monitored by writing a report or by discussing reading in classroom time.

Nuttal (1996) believes that extensive reading helps students to improve their level of English, arguing that extensive reading is not only the easiest but also the most effective way of improving reading skills. Day and Bamford (1998b) in agreement state that, ‘until students read in quantity, they will not become fluent readers’ (p. 1). Several pieces of research support this view. Elley and Mangbhai’s (1983) research saw excellent improvements in students’ language skills over a 20-month course compared with those students taught using a traditional Audio-Lingual method. Lao and Krashen’s (2000) experiment over 14 weeks resulted in students increasing their vocabulary by 3,000 words. While students taking part in Macalister’s (2008) study into EAP and extensive reading reported increases in vocabulary, increased awareness of writing styles, improvements in grammar and increased reading speeds.

Drawing on these definitions and the results of previous research, participants in this current study were asked to read whatever they wanted in their free time; they were told they could read as much or as little as they wished; and that they would not be formally assessed in any way (although they would be asked to talk about their reading every week).

In order to assess the amount of reading the students did, they were asked to complete a questionnaire about their free-time reading habits at the beginning and then at the end of the course. The initial questionnaire (Appendix 1) was distributed at the beginning of the second week of the semester, while the final questionnaire (Appendix 2) was given out in week 14.

In an effort to promote free-time reading, two methods were employed during class time: firstly, they were asked to talk about their free-time reading; and secondly, they had access to a classroom magazine library.

According to Nuttal (1996) discussing reading is a good way to encourage students to read further. Therefore, the activity ‘Tell Us About It’ (Bamford 1993) took place every week for about 10-15 minutes (see Appendix 3). This was an informal discussion where the students in small groups of 3 or 4 talked about what they had read over the previous week, whether they had enjoyed it and whether they would recommend it to the others in the group.

Magazines (including New Statesman, New Scientist and National Geographic) were made available in the classroom for students to borrow. This was to ensure that students struggling for something to read would have instant access to material for home use. It was made clear that borrowing the magazines was not compulsory.

At the beginning of the course all of the students admitted to reading in quantity in English (see Table 2 below). Furthermore, they stated that they read a variety of material including the internet, newspapers and story books. Their questionnaires stated that they read on average 8 hours per week with 2 hours being the least and 12 hours the most.

Table 2: Materials read during participants’ free time

| What kinds of things do you read in your free time? | Number of respondents who read this kind of material |

| The Internet | 9 |

| Fiction, novels or stories | 5 |

| English textbooks | 4 |

| Non-fiction | 2 |

| Newspapers | 4 |

| Magazines | 3 |

| Other | 2 |

On the initial questionnaire the respondents gave the following reasons for not reading in English:

Table 3: Factors preventing reading at the beginning of the semester

| At the moment what if anything prevents you from reading in English? |

| Too much unknown vocabulary | Time | Laziness | Money | Nothing | No answer |

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

Students made comments such as:

I don’t have much time. Sometimes, I can’t read because it is difficult to understand.

…read in English is difficult and requires more time to understand, so I prefer reading in Arabic Language.

In academic Reading its very easy because I know vocabulary, but in magazines or newspapers it’s difficult however with phrasal verbs or idioms.

I like to read a book in Korean, but reading in English is difficult. It takes much time. So at this moment, I like to read a simple and easy book only.

Unfortunately, due to personal circumstances only five of the original nine students actually completed the course and as a result completed the final questionnaire. A summary of their comments and quotations is presented below.

Abdulaziz was not too enthusiastic about Tell Us About It, stating that he was already motivated to read before doing this. However, he did read through the class magazines. Although Abdulaziz enjoyed reading, he was still facing some problems: a lack of time, too much unknown vocabulary and a preference to read in Arabic.

Nasser believed that discussing his reading habits motivated him to read. Furthermore, he read the classroom magazines once a week. He listed time, the vocabulary load of texts and a preference to read in his own language as reasons preventing him from reading more.

For Norah the main problem was prioritising her reading: ‘I have to read IELTS text than read magazine or any entertainment reading’. She also stated that time, due to having homework and looking after a family, as well as a lack of vocabulary prevented her from reading more. She stated that reading more motivated her to read rather than discussing what she had read. She took a classroom magazine every four days.

Bo Leung believed that nothing prevented him from reading. He seldom read the classroom magazines: ‘Because of difficult vocabulary, some books and articles are difficult to read, So I try to read intermediate level fiction books’. Discussing his reading habits motivated Bo Leung to read, whereas the classroom magazines did not.

Shin stated on her final questionnaire that ‘I am enjoying reading in English now. Because, I am getting used to read something in English’. However, describing the classroom magazines she stated that ‘sometimes the reading materials are difficult to read for me. I have so many vocabularies to find that I’ll take much time’. As a result she only read the classroom magazines 2 or 3 times during the semester. Discussing reading habits motivated Shin to read: ‘When I heard about the interesting book from classmate, I want to read it’. She was prevented from reading because she found it difficult and preferred reading in Korean. She also stated that she could not get hold of the material she wanted to read.

The tables below summarise the factors preventing reading at the end of the semester (Table 4), and the number of hours the five finishers recorded in their questionnaires (Table 5).

Table 4: Factors preventing reading at the end of the semester

| What factors have prevented you from reading? |

| Too much unknown vocabulary | Time | Preference to read in own language | Doing practice for IELTS | Nothing |

| 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

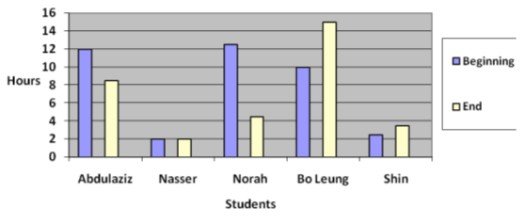

Table 5: Hours spent reading according to questionnaire answers

On their initial questionnaire the respondents dedicated, on average, 8 hours per week to reading. This ranged from two to twelve hours per week, with none of the students recording 0 hours per week. This contradicts the initial observation that EAP students do not read in their free time. It is possible that the respondents might not have recorded the true amount of reading they actually did due to the Hawthorne Effect, meaning that ‘participants (of a study) perform differently when they know they are being studied’ (Dörnyei 2007: 53). In other words, respondents give answers which they believe are expected of them rather than answering truthfully.

At the end of the study, the remaining participants recorded between 2 and 15 hours of free-time reading per week, with an average of 6 hours 45 minutes per week. Although the maximum number of hours per week increased – from 12 to 15 – the average decreased from 8 to 6 hours 45 minutes. It could be argued that the aim of motivating students to read had actually failed, as the students on average recorded fewer hours. Yet it could also be argued that as the semester progressed some students were more concerned about gaining the relevant score on the IELTS examination than reading. The three students who needed to take the IELTS examination (namely, Abdulaziz, Nasser and Norah) all recorded either a decrease or no change in the amount of reading they did. Indeed, Norah claimed that she spent most of her time towards the end of the course studying for the examination. On the other hand, both Bo Leung and Shin, who were in the UK to improve their level of English and did not consider taking IELTS, recorded an increase in the number of hours they spent reading. For example, Shin reported that she was reading more as the course progressed. In her final questionnaire she admitted that she was ‘getting used to reading English’ and therefore as a result reading more. This agrees with Nuttal (1996) and Day and Bamford’s (1998a) observations that as students read more, they will find reading easier and thus read even more.

As well as exam preparation discussed above, time and vocabulary load were both given as reasons for not reading. When giving lack of time as a problem, the students stated that homework from other teachers along with domestic duties prevented them from dedicating more time to reading. The vocabulary load of texts presented a further problem, as students claimed that the amount of unknown vocabulary in a text prevented them from enjoying it and as a consequence led them to being frustrated with the text and ultimately dropping it. This is consistent with Schmitt and Schmitt’s (2005) belief that ‘second-language learners have long realized the importance of vocabulary for improving language proficiency’ (p.vi).

The classroom magazines were generally viewed favourably. Three of the finishers read them on a weekly basis believing they were useful in improving their knowledge and vocabulary. Furthermore, the availability of reading material allows students to browse through material in a similar way to using a real library by giving them the opportunity to choose their own reading material (Nuttal: 1996). The two students who did not read them regularly – Bo Leung and Shin – did, however, read other material. It could, therefore, be argued that having magazines available did not actually motivate them to read these texts, but did motivate them to read something else of their own choice (Day and Bamford 1998a).

Consistent with Nuttal’s (1996) observation, most of the students in this case study believed that talking about reading motivated them to read. They were able to reflect on what they had read and then share this with their classmates. For example, Shin, believed that talking about reading persuaded her to read stories other students had read. On the other hand, Norah stated that talking about reading did not motivate her to read: only reading motivated her to read more.

The main limitation of this piece of research was both the size and composition of the group investigated. Although the research was in effect a case study, it would be hard to extrapolate from such a small group to every other student studying at the ELTC, or indeed to every other EAP student. Furthermore, the students investigated were both highly motivated to study and were already quite proficient in English at the beginning of the semester. A further limitation was due to the number of students who finished the course before the last questionnaire could be completed: that is, four students finished after 12 weeks and as a consequence did not complete the final questionnaire.

From their questionnaire answers it could be concluded that this group of students did some reading in their free time. However, over the course of the semester only two of the five students, who completed their final questionnaire, actually read more. It appears that there were a number of reasons which prevented them from reading more. The main factors for this appear to be lack of time, preference to do IELTS practice and the difficulty (that is, the vocabulary load) of the texts the participants were reading.

There appear to be several solutions to this problem. Firstly, students may need to be encouraged to manage their time better. This would ensure that they have adequate time to dedicate to reading: a time-management course might address this problem. Secondly, students could be given reading homework; that is, instead of teachers setting homework tasks such as grammar exercises or written tasks, they could be asked instead to read for a set time and then record this in a diary. Green (2005), for example, supports this believing that students need curricula time for private reading. This could also mean that some classroom time could be dedicated towards reading at the expense of traditional classroom activities.

Gaining the relevant score on this test ensures that students get a place on a course in higher education. However, the fact that passing this examination then became the sole focus for some students distracts from the main point of the EAP course: i.e. preparation for academic study. A solution to this problem would be to separate academic English classes from IELTS preparation classes. This would ensure that students who needed IELTS practice would get lessons dedicated to this end. This may ensure that students would not feel the need to do endless IELTS practice tests in their own time, and would as a result dedicate more time to reading.

Jordan (1997) suggests that the vocabulary of EAP students should be much larger than the core word list of 2,000 - 3,000 words. Moreover, this vocabulary should also include core academic terms as well as subject specific words. In this current case study several students would agree, stating that they found reading difficult due to a lack of vocabulary. Therefore, in order to enjoy free-time reading and improve reading skills in general, a programme of extensive reading could be complemented with classroom time dedicated to learning vocabulary (Sonbul and Schmitt 2010).

Finally, the main conclusion from this case study seems to be that in order to motivate students to read more in their free time, they need to be reminded of reading by their teacher as often as possible. By having a classroom library available ensures students see books and magazines everyday and are able to follow their curiosity and borrow as many as they wish. Talking about books on a regular basis ensures students not only have reading in their minds, but are also able to make recommendations to their classmates and follow up recommendations made to them.

Alexander, O., S. Argent and J Spencer. 2008. EAP Essential: A teacher’s guide to principles and practice. Reading: Garnet Publishing Ltd.

Bamford, J. 1993. ‘Tell Us About It’ in R. Day (ed.) New ways in Teaching Reading. Illinois: TESOL. p.3.

Bamford, J. and R. Day. 2004. Extensive Reading Activities for Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, D. 2009. ‘Why and how textbooks should encourage extensive reading’. ELT Journal 63/3: 238-245.

Day, R. and J. Bamford. 1998a. Extensive Reading in the Second Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Day, R. and J. Bamford. 1998b. ‘Extensive reading: what is it? Why bother?’. The language Teacher Online 21/5.

Dörnyei, Z. 2007. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elley, W.B. and F. Mangubhai. 1983. ‘The impact of reading on second language learning’. Reading Research Quarterly 19: 53-67.

Green, C. 2005. ‘Integrating extensive reading in the task-based curriculum’. ELT Journal 59/4: 306-311.

Jordan, R.R. 1997. English for Academic Purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lao, C. Y. and S. Krashen. 2000. ‘The impact of popular literature study on literacy development in EFL: more evidence for the power of reading’. System 28: 261-270.

Macalister, J. 2008. ‘Integrating Extensive Reading into an English for Academic Purposes Program.’ The Reading Matrix 8/1.

Nuttal, C. 1996. Teaching reading skills in a foreign language (2nd ed.). Oxford: Heinemann.

Schmitt, D. and N. Schmitt. 2005. Focus on Vocabulary: Mastering the Academic Word List. New York: Pearson Education.

Sonbul, S. and N. Schmitt. 2010. ‘Direct teaching of vocabulary after reading: is it worth the effort?’. ELT Journal 64/3: 253-260.

Please answer these questions regarding your free-time reading in English. That is, think about all the reading you do in English which is not related to your English lessons.

- What kind of things do you read in your free time (please list as many things as possible)?

- How much time to do you think you spend reading in an average week?

- At the moment what if anything prevents you from reading?

- Use this space to add any further comments you have about reading

Please answer these questions regarding your free-time reading in English. That is, think about all the reading you do in English which is not related to your English lessons.

- What kind of things have you read in your free time over this semester?

- How much time have you spent reading in your free time per week this semester?

- What factors have prevented you from reading?

- Has discussing your reading habits every week motivated you to read?

- How often have you read the magazines available in the classroom?

- Use this space to add any further comments you have about reading

In groups of three or four I want you to briefly summarize and discuss what you have read over the last week.

Things to talk about:

- A brief summary of what you have read over the last couple of weeks

- Your opinion about what you have read

- Would you recommend anything

The Teaching Advanced Students course can be viewed here

|