Editorial

This article originally appeared in ‘The Teacher’ magazine.

Part one Language Domesticated (1): Does Foreign Language Learning Have to Hurt?

appeared in HLT, Dec 2011.

Language Domesticated (2): Does Testing Cause Learning…?

Grzegorz Śpiewak, Poland

Grzegorz Śpiewak is a teacher, teacher trainer, EFL project manager, adviser and author. He is also a former lecturer and deputy director for PE at the Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw, currently affiliated with New School, New York, where he teaches EFL methodology at an on-line MATESOL programme. A former IATEFL Poland president, he is now head ELT Consultant for Macmillan Polska, President of DOS-Teacher Training Solutions and co-founder of deDOMO Education, lead author of Angielski dla rodziców deDOMO.

E-mail: grzegorz@e-dos.org

Menu

Introduction

(Language) education begins at home

Past perfect or future perfect?

Putting testing to the test

Error as terror or as step?

Noticing (partial) success

Bibliography

Welcome to episode 2 of a new article series brought to you by deDOMO Education. The overall purpose of the series is to introduce an alternative approach to foreign language education, tried and tested with considerable success recently.

We started out last month by exploring some parallels between foreign language learning and traumatic initiation rituals. This month we take on the difference between testing and teaching, in an attempt to reduce the potentially highly demotivating effects of so-called ‘fair, objective assessment’ on the process of learning anything, especially a foreign language.

In the concluding paragraph of episode 1 of the ‘Language Domesticated’ series, we stated our mission as 21st century English language educators in terms of reducing the foreigness of the process so that it doesn’t feel like a traumatic initiation ritual. For language learning to hurt less, we argued, one needs to call into question some of the established attitudes (e.g. towards language errors) and pedagogical tools (such as grades). The inspiration for this might come from the home, we added somewhat programmatically. Now time has come to say how.

One major difference between how school and home educate is that Mum and Dad, in marked contrast to the teacher, love their child(ren). It sounds trite, doesn’t it? And yet it’s quite critical for everything else we want to say. The point is that parents have a natural, biological imperative to make their child feel happy. They are very, very generous with rewards and praise, verbal and non-verbal. So what, one might react: school is about giving objective feedback, bad grades are part of the package, and that’s that. In spite of the Polish saying, school is not a second home.

Well, yes and no. On the one hand, it would be very naïve (and unfair, to be honest) to expect teachers to love their pupils in parent-like fashion. On the other, parental praising reflex ties in very well with what the contemporary science of motivation has established: everyone needs a carrot, kids and adults alike. More carrot, more motivation. And, conversely, more stick, more demotivation, even if giving an otherwise perfectly fair and objective failing grade gives the teacher a feeling of control. The latter, we hear more and more from motivation coaches, is a dangerous illusion. One can of course discipline a pupil with a “jedynka” (an “E”), but certainly not motivate him or her to learn afterwards. Not convinced yet? Think of the last bad grade you gave: did it happen at or towards the beginning of a lesson? If so, can you recall the attitude of the learner in question for the rest of that lesson? Was s/he cooperative? Eager to take in what you had to offer? My guess is: not really…

This next section is not going to be about advanced tense constructions. Rather, I wish to explore further the (de)motivating effects of testing on learning. If you switch in testing mode, you are crucially oriented towards the past rather than future. To put it yet differently, a grade given in order to assess a piece of work already produced is an act of testing, not teaching! It is a complaint about the learner’s past, an unfulfilled wish that it had been perfect.

Can a grade ever be a teaching tool, though? Yes, it can. But only if it is being given to nudge the learner along the learning path, induce him or her to try harder the next time they attempt a task. The one they have already done is in an important sense irrelevant for their learning! It’s done and over with, unless the teacher has a way to make the learner use their already existing output as a draft that they will re-do so that it will be perfect one day.

Make no mistake: the author is not naively calling for abandoning traditional assessment methods altogether. What could – and should – be questioned is all those situations when testing and teaching get mixed up, at the expense of the latter. The problem has been gaining attention in recent years, most recently in the January 2011 issue of ELT Journal, where Icy Lee talks of a “paradigm shift in assessment that places more emphasis on the relationship between teaching, learning, and assessment” and advocates “assessment for learning: using assessment to promote learning” as superior to the traditional “assessment of learning: using assessment for primarily administrative purposes” (p.1, stress added). In order for the shift to really take effect, the teacher needs to perform some crucial mental gymnastics and stop searching for errors. Yes, I know, spotting errors in our what our learners say and write is as much a reflex reaction for any teacher as rewarding and praising is intuitive for any parent. But that’s precisely where home can offer us some valuable inspiration. In order to promote learning, we need to teach more (and test less)!

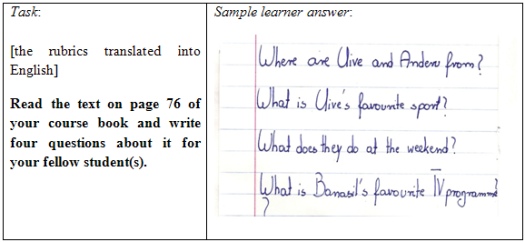

I’m sensing disbelief in many a reader, so let’s take … a little test. Mind you, no grades will be given, unless you choose to grade yourself . Your task is to evaluate a piece of homework, produced by a 4th grader in response to the following task:

Chances are you have not given your top grade. If so, you are in very good company: some 60% of language teachers around Poland have done the same when I did this exercise as part of a teacher development programme recently. The reason is almost too obvious to mention: the glaring grammatical error in sentence 3.

Common as the above teacherly reaction is, it deserves a very serious consideration. First, what was the task instruction, precisely?? Was it phrased as a grammar exercise (‘write 4 questions in the present simple tense’), or as a reading comprehension task? The correct answer is: the latter. Now, given the rubric, has the student demonstrated their comprehension or not? No bickering, straight answer please. Well, s/he has. 100%, no doubt about that. Question 3 does contain an obvious error, but as such is no less comprehensible than the other three. Here we touch upon a problem of what has come to be known in applied linguistics as ‘error gravity’. Simplifying massively, it is to do on the one hand with the extent to which a given departure from the accepted linguistic norm actually impacts on intelligibility of a given utterance, and on the other hand, it’s about the differences in how NNS vs. NS assessors perceive the seriousness of a given type of error. See for ex. McCretton, E. & N. Rider (1993).

Interestingly, imagine for the sake of argument that the above four sentences are produced during a matura exam. Given the current matura grading criteria, they would surely score all the relevant points, including those for linguistic accuracy. Why is it that the output graded as less than fully satisfactory when produced by a 4th grader is to be judged as completely fine when the student is 10 years older? Has it aged gracefully, like wine?!

Sarcasm aside, the point is certainly not that the new matura defocuses accuracy (which it does), but that any lowering of the grade is a clear case of error-spotting reflex in the teacher. Yes, the error did get duly noted. But has the kid actually learnt anything from that ‘B’? Sadly, I think s/he has. Lesson 1: no matter what the task instruction says, remember it’s all about grammar! Lesson 2: the teacher is not on your side but will try to catch you out so you’d better be careful next time! Lesson 3: don’t take linguistic risks, play it safe lest you err and get punished.

Mind you, the task in question wasn’t even an official, high-stake test, but a mere homework assignment. And yet if you still insist on lowering the grade, you teach your learners that error is terror, a sin, something to avoid at all cost. It is clearly not a step, in spite of what virtually all EFL methodologists are saying these days…

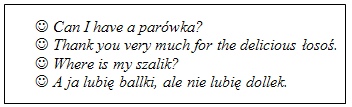

Again, I’m sensing growing resentment in some readers. Shall we then be lenient and permissive, pretend we haven’t noticed the error?! What would an English-speaking parent say if the homework went uncorrected? Ah, yes, the parent! Before I address the two questions, let’s indeed talk about parental reaction to child’s errors, such as misbehaving at home. A parent will above all make sure the child knows that s/he is loved and accepted before his/her behavior is discussed. A parent will also notice every little bit of success and make sure the kid knows that, too. This is what we attempt to make contact with in the ‘deDOMO’ programme, when we encourage parents to praise children’s partial success evident with utterances like:

źródło: Angielski dla rodziców deDOMO. Przewodnik metodyczny

deDOMO Education 2011

As educators (parents as well as language teachers, arguably), we have a crucial choice when faced with attempts like these: we can either scorn them for mixing the two linguistic codes, not knowing the English equivalents of ‘parówka’, ‘łosoś’ or ‘szalik’, OR we can praise them for [a] a fluent use of the lexico-grammatical frames like ‘Can I have a’ or ‘Where’s my …’, and [b] for abstracting those super-frequent (and as such highly useful) chunks from the utterances that the child has encountered previously, such as ‘Can I have a lollipop? ’ or ‘Where’s my hat? ’. Scorning is testing, praising is teaching – that much is obvious by now, I hope.

Returning to the issue of “does they do” in sentence 3 above: a ‘deDOMO’ response is two-fold. First, praise, for successfully completing the reading comprehension task. No reservations, full points. Yes, completely parent-like, after all we have set out at the beginning of this text to seek inspiration in the home. Then a critical teaching moment: because you have done so well in this task, I am going to give you a tip. Next time you ask a question like no.3, remember to use ‘do’ instead of ‘does’. The difference is small but striking: the kid has first been informed that s/he has succeeded in something (a carrot!) and thus been prepared to take in linguistic feedback (a small stick)! The teacher has also shown the learner that his/her error is but a welcome step on a path towards an even more successful performance in the future. And, the more learning steps you take, the faster you go. That’s what good teaching, any real teaching, is arguably about.

To be continued in the next issue of HLT.

McCretton, E. & N. Rider (1993), ‘Error gravity and error hierarchies’. International Review of Applied Linguistics 31 (3): 177-88

Lee, Icy (2011),‘Feedback revolution: what gets in the way?’, ELT Journal volume 65/1: 1 -12

Please check the Methodology and Language for Kindergarten Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|