The Impact of Teachers’ Communication Skills on Teaching: Reflections of Pre-service Teachers on their Communication Strengths and Weaknesses

Sng Bee Bee, China

Dr SNG BEE BEE is currently an Associate Lecturer in Communications with the University at Buffalo, SIM Global Education, Writing Skills in S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Communication for Teaching in the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. In the past, she has also taught Communication Skills in the Language and Communication Centre, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for nine years . She graduated with an E.D.D. specializing in Education Management from the University of Leicester, UK. Her research interests are educational change, English for Specific Purposes, English as a Foreign Language and more recently, e-learning. E-mail: beesng@gmail.com

Menu

The importance of communication skills for teachers

Background of language use in the classrooms in Singapore

Research methodology

Preservice teachers’ perception of their communication strengths

Chinese language pre-service teachers’ perception of their communication weaknesses

General track pre-service Teachers’ perception of their communication weaknesses

Analysis and conclusions of reflection points of preservice teachers

Bibliography

Effective communication skills are really important to teachers in their delivery of pedagogy, classroom management and interaction with the class. In a multilingual society like Singapore, teachers struggle with decisions about the variety of English to use, the standard quality of their English, their English language proficiency and the effectiveness of their communication skills. This study examines Singapore’s preservice teachers’ perception of their communicative strengths and weaknesses as reflected in their journals. The issues which emerged in this study are vital to the understanding of teacher education in multilingual and multicultural societies.

Communication skills can be defined as the transmission of a message that involves the shared understanding between the context in which the communication takes place (Saunders and Mills, 1999). Communication takes place through channels. Within the teaching profession, communication skills are applied in the teachers’ classroom management, pedagogy and interaction with the class (Saunders and Mills, 1999). In addition, teaching speaking skills is important in teacher education (McCarthy and Carter, 2001). Despite this, there was little literature and research identified on the communication skills of teachers and for this reason, this study was conducted. A course on communication skills is included in the program of teacher training for teachers-to-be in Singapore. Teachers picture themselves standing in front of a class presenting and explaining specific subject knowledge, questioning and disciplining students. Consequently, they are concerned with how clearly and effectively they are communicating this knowledge and other intended messages. In the context of Singapore, where there exists different varieties of English and other languages, teachers are also concerned about the accuracy of their pronunciation. In addition, the perception of the standardness of their spoken English is perceived to be important to them. In addition, pre-service teachers enter into a teaching training program with different expectations and beliefs about teaching (Calderhead and Robson,1991). The complexity of language use in Singapore, together with this variety of expectations, necessitates a study on pre-service teachers’ perceptions of their communication skills in English. This situation is accentuated by the Singapore government’s concern with the variety of English taught and used in Singapore. Singapore government wants to promote the use of a variety of English that is as close as possible to standard Singaporean English rather than the colloquial variety known commonly as Singlish that is rampantly used in Singapore. It is also believed that teachers are model of language use for students and standard English should be used in the classroom.

The focus of this study involves an analysis of teachers’ reflections of their communication strengths and weaknesses. An investigation of teachers’ self-perception is important as their beliefs influence their classroom practice. Teachers’ beliefs are embodied in their thinking inward and recognizing their beliefs about their teaching. These beliefs are drawn from their past experiences. Subsequently, they look outward at institutional, classrooms realities, expectations, and find a match between these two sets of expectations (Jones and Fong, 2007). Such beliefs influence teachers’ perception, judgment and behaviour, which in turn, influence what they say and do in the classroom (Johnson, 1994). Secondly, teachers’ beliefs can be shaped by the dominant values of their institutions (Jones and Fong, 2007). Such pressure to conform can cause teachers to comply with expected behaviour (Jones and Fong, 2007). Richards (1998) claims that teachers engage in a personal construct of a workable theory of teaching rather than conform to experts’ definition of teaching principles and approach. The teacher does this in the midst of social and cultural constraints of the institution. For this reason, research about teachers’ beliefs and perception of their communication skills is vital as it may help us to understand how teachers perform in the classroom.

This study hopes to trace the development in the pre-service teachers’ perception of their communications and the implications this perception may have in their classroom communication. It is written that pre-service teachers go through four kinds of perceptual change. Firstly, they may discover that their initial beliefs or images have been incorrect. This may be followed by the acquisition of new technical know-how; discovery of new ways of categorising experience and acquisition of new self-knowledge (Shapiro, 1991). A study done by Lee (1997) reveals the importance of communication for effective teaching. She asserts that people are the centre of schools and communication is the foundation. Her study shows that all pre-service teachers bring to their teacher education program some knowledge of communication skills though they may not be able to describe this. Her study proves that communication skills should be taught explicitly and implicitly through the teacher trainer’s modeling of communication skills. In the teacher education program, pre-service teachers should identify the relationship between theoretical learning and practical application of communication skills. Another study done by Jones and Fong (1999) discovers that at the initial stage of teacher education, pre-service teachers perceive themselves as the center of communication and transmitter of knowledge. After they have completed their practical internship in the schools, they recognize the importance of the communication interaction between the teacher and the class. They have learned to integrate communication skills into their teaching practice (Jones and Fong, 1999).

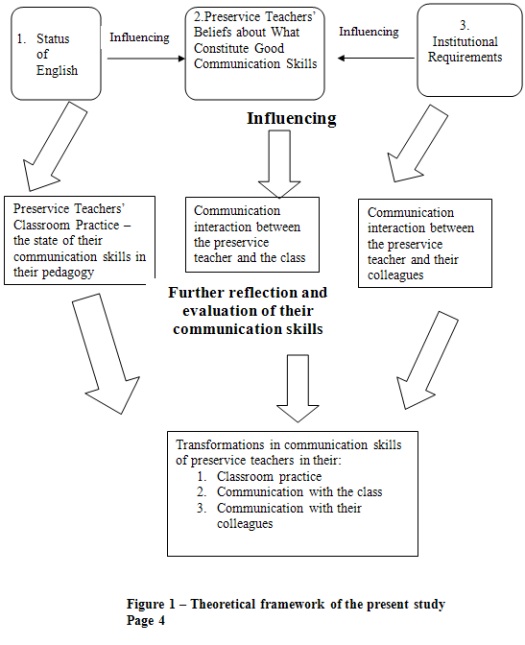

The present study therefore attempts to identify the Singapore’s preservice teachers’ perception of the strengths and weaknesses of their communication skills. This study integrates the findings about the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and their communications skills in the studies done by Jones and Fong (1999), Lee (1997), and Shapiro (1991) into a theoretical framework represented the figure 1. This theoretical model shows that teachers’ communication skills in the classroom are influenced by both their inner beliefs about what constitute good communication skills and external forces in the form of societal perception of the status of different English varieties and institutional practices. For this reason, it is important to examine preservice teachers’ perception of their communication strengths and weaknesses.

Past studies have shown that Singaporean teachers face a tension with language use due to social-cultural identity and economic capital (Rubdy, 2007 and Alsagoff, 2007). Singaporean teachers hold diverse and ambivalent views about the use of British variety, Singaporean Standard English (SSE) and the more common Singaporean Colloquial English (SCE) in the classroom.

Teachers and education policy-makers in Singapore face the dilemma of balancing the positions of the various varieties of English used in this a very diverse multilingual environment. English functions as a neutral language in Singapore in bringing the diverse ethnicities and cultures together. The four official ethnicities in Singapore are Malays, Chinese, Indians and Eurasians. Of these ethnicities, Chinese forms the greatest majority, namely, 70% of the population. In addition, there are internationals from all over the world living in Singapore. Therefore, English plays the vital role of nation building and enabling the nation to engage in global trade and investments (Tan and Rubdy, 2008). At the same time, the government fears that Singaporeans will become ‘Westernized’ with the exposure to English, so ‘mother tongue’ or the languages of the ethnicities in Singapore is taught to balance the perceived effects of English (Tan and Rubdy, 2008). This multilingual environment in the classroom is complicated by the popular use of Singaporean Colloquial English or Singlish. Singlish serves an important function in Singapore society in that it is an identity marker for the people (Tan and Rubdy, 2008). This study examines the preservice teachers’ concern with their subconscious lapse into use of Singlish and the management of students’ use of Singlish in the classroom. It also discusses the preservice teachers’ view of how Singlish can be a linguistic resource in their teaching.

One of the prominent concerns of the pre-service teachers is that they may lapse into the use of Singlish in the classroom. This concern is reflected in research on communication in the multilingual classroom which finds that language use differs from policies which are prescriptive and monolingual (Tan and Rubdy, 2008). Singlish, or Singapore Colloquial English (SCE) is a variety commonly used among Singaporeans. Singlish is marked by omission of copulas, auxiliaries, articles, past tense markers and auxiliary ‘do’ in questions (Rubdy, 2007). In addition, one of the major characteristics of this variety is the rampant use of pragmatic particles like ‘Ah’, ‘leh’, ‘leh’ and ‘lor’ (Rubdy, 2007). It is seen as an impediment to the development of students’ literacy skills in standard English (SSE) and as a degeneration of English (Rubdy, 2007). Therefore, there was a strong disapproval towards teachers who use this variety (Rubdy, 2007). Another study shows that teachers hold contradictory views about use of Singlish in the classroom and considers Singlish as both deficient and useful (Farrell and Tan, 2007). Despite this view, teachers feel Singlish is useful in helping them explain difficult content, build rapport with students, inject fun and humour in the class, and serves as a time-effective means of communication and springboard for teaching of standard English (Rubdy, 2007; Farrell and Tan, 2007). These dualistic perspectives of use of Singlish are echoed in the reflections of the pre-service teachers involved in this study. One of the research questions the present study addresses is whether the pre-service teachers view the use of Singlish as their communicative strength or weakness and how they reconcile the paradox concerning its use in the classroom. The other research questions that this study addresses relate to the preservice teachers’ perception of their communicative strengths and weaknesses in the areas of verbal and non-verbal communication as well as other paralinguistic features like pitch and tone of voice.

A study done on teachers’ view of spoken grammar among British teachers reveals that two third of the teachers felt it is important to expose learners to the native speaker variety of English, while a quarter expressed reservations about the grammaticality of certain spoken forms (Timmis, 2002). Conversely, another similar study done by Goh (2009) shows that Singaporean teachers held divided opinion about the use of the exonormative features of British English as this variety competes with the local English variety for acceptance. The teachers involved in this study found this British variety less useful as they already had their spoken variety in the form of Singlish (Goh, 2009). Past studies done on the use of Singlish in Singapore involve the linguistic features of Singlish. However, there is little literature on how Singaporean teachers adapt their use of Singlish and Singaporean Standard English to the different communicative contexts in schools. In this study, the teachers reflected on how Singlish was useful to them for establishing rapport with students and their parents.

Therefore, this review of past studies show the complexity and number of issues that Singaporean teachers face in classroom language use. This study aimed to identify Singaporean pre-service teachers’ perception of their communicative strengths and weaknesses. It is important to research teachers’ beliefs as these beliefs influence perception and judgment; play a role in how information on teaching is translated into classroom practices. In addition, understanding these beliefs is essential in improving teaching practices and teacher education programs (Kagan, 1992).

The preservice teachers were invited to write about their perceived strengths and weaknesses in communication skills during and at the end of their course. In their journals, the preservice teachers reflected on their communication strengths and weaknesses.

This study employed content analysis as its research methodology. The researchers first read the reflections of the preservice teachers for an overall understanding of their communication strengths and weaknesses. Then, in the analysis of data, the types of communication strengths and weaknesses they identified were coded and categorized. The data were coded and categorized into the following areas: verbal; non-verbal; paralinguistic cues; linguistic features and varieties of English. The frequency of these specified views were counted and compiled in tables and graphs. This quantitative compilation of quality data allowed the researchers to make a judgment of the prevalence of views about the preservice teachers’ communicative strengths and weaknesses. The results were presented in the following section.

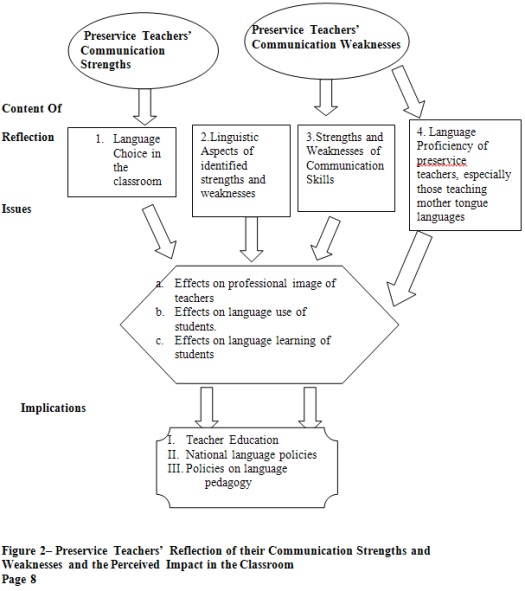

This study involved 35 preservice teachers, consisting of Chinese, Malay and Indian ethnicities. In total, 35 reflection journals were analyzed, consisting of 20 preservice teachers who would be teaching Malay and Chinese languages (known as mother tongue languages in Singapore) and 19, who would be teaching other subjects like science, maths etc. The second group of preservice teachers was known as the General Track preservice teachers. All the preservice teachers would be teaching in the Singapore primary schools. The points identified by the preservice teachers as their communicative strengths and weaknesses were analyzed along the lines of whether they were verbal or non-verbal; whether they were linguistic in nature or relate to communication skills, or to choice of varieties of English to use in the classroom. In general, these issues can be summarized in the chart (figure 2) below:

The preservice teachers were invited to write about their perceived strengths and weaknesses in communication skills during and at the end of their course. In their journals, the preservice teachers reflected on their communication strengths and weaknesses.

This study employed content analysis as its research methodology. The researchers first read the reflections of the preservice teachers for an overall understanding of their communication strengths and weaknesses. Then, in the analysis of data, the types of communication strengths and weaknesses they identified were coded and categorized. The data were coded and categorized into the following areas: verbal; non-verbal; paralinguistic cues; linguistic features and varieties of English. The frequency of these specified views were counted and compiled in tables and graphs. This quantitative compilation of quality data allowed the researchers to make a judgment of the prevalence of views about the preservice teachers’ communicative strengths and weaknesses. The results were presented in the following section.

This study involved 35 preservice teachers, consisting of Chinese, Malay and Indian ethnicities. In total, 35 reflection journals were analyzed, consisting of 20 preservice teachers who would be teaching Malay and Chinese languages (known as mother tongue languages in Singapore) and 19, who would be teaching other subjects like science, maths etc. The second group of preservice teachers was known as the General Track preservice teachers. All the preservice teachers would be teaching in the Singapore primary schools. The points identified by the preservice teachers as their communicative strengths and weaknesses were analyzed along the lines of whether they were verbal or non-verbal; whether they were linguistic in nature or relate to communication skills, or to choice of varieties of English to use in the classroom. In general, these issues can be summarized in the chart (figure 2) below:

The General Track preservice teachers identified their strengths as fluency in speech though they felt at the same time, that they tended to speak to fast. In terms of the varieties of English, they felt that there was an appropriate occasion and context for the use of Singapore Standard English (SSE), and the colloquial variety, Singlish. In the reflection journal of one member:

‘Singapore Standard English is important as the teacher is a role model. If the students receive exposure to Singlish on a daily basis, they will become accustomed to using Singlish themselves.’

This duality of attitude towards the use of these two varieties of English in Singapore is reflected in another member’s journal:

‘SSE important. The teacher is a role model. If Singlish is used, it may convey an impression of lack of proficiency to superiors. However depending on the relationship, a teacher may use some Singlish to preserve identity.’

It seems that this group of preservice teachers felt there was a right time and context to use SSE and Singlish. They felt strongly that SSE should be useful in giving instructions and delivery of subject content, but Singlish could be used to build rapport with students. Singlish therefore served the function of building identity and interpersonal relationships, while SSE was important in helping the teachers preserve a professional image and setting a role model for the use of the Standard variety. Along this line, the members of this group also felt it was important for teachers to speak with accurate pronunciation in accordance to SSE standard.

In terms of the paralinguistics aspects of speech, this group of preservice teachers felt that their strengths were found in their ability to adapt their pitch and tone of voice to their audience and empathize with their audience. According to a few of them:

‘We must engage audience through varying pitch, tone, rate of talking and articulation, pause for dramatic effect.

‘Enthusiasm and energy important, not just content knowledge.’

‘A teacher should be approachable, and s/he needs to take note of non-verbal communication , for example, relaxed stance, eye-contact, paraphrase words, encouraging. She also needs to be a teacher also needs to be non-judgemental.’

This group of preservice teachers saw the importance of possessing effective communication skills in their delivery of subject content in the classroom:

‘A teacher should have confidence in delivery, able to explain ideas, theories in a clear and coherent, and relate to audience appropriate manner. The teacher should also be an active listener.’

In contrast with the General track group who viewed the importance of communication skills in the light of classroom teaching, the Mother Tongue preservice teachers evaluated the importance of possessing effective communication skills in terms of communication using English with their colleagues and superior. Since they did not use English in their classroom teaching, they merely used English when communicating with fellow teachers, Heads of Departments and principal.

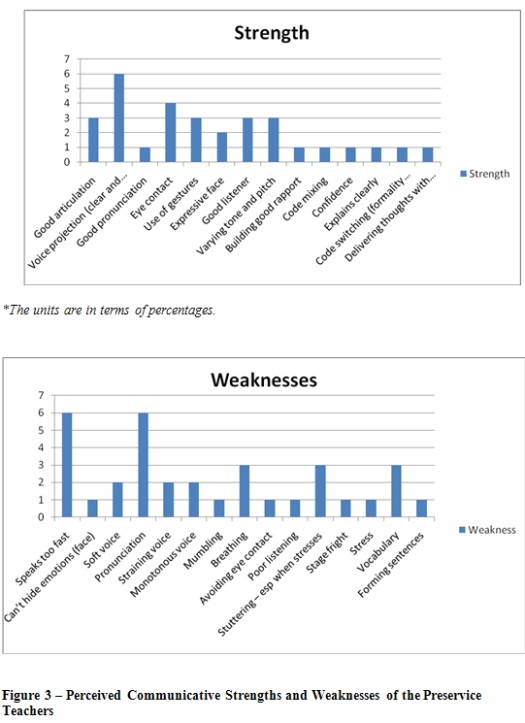

The Mother Tongue group identified aspects of communication skills related to interpersonal communication to a greater extent than the General Track group. They wrote in their reflection journals that factors such as maintaining eye contact, and other paralinguistic features to show affirmation like nodding, smiling, showing appropriate facial expressions and tone of voice (31% o r 11 of respondents, refer to figure 3). The reason for this could be they viewed the importance of communication skills in English in the light of communication with colleagues and superiors. It could also be that culturally, as Chinese and Malay people, they paid much more attention to politeness and building rapport.

Compared with the General Track group, the Mother Tongue group placed importance on the place of humour and paraphrasing (12.5% or 4 respondents, refer to figure 3), apart from using appropriate tone and register in communication. Again, the reason can be cultural in that humour is seen as placing an important role in the interpersonal aspect of communication within their cultures. Paraphrasing is important as it is an effective tool in clarifying what is said.

In terms of verbal communication, the respondents felt that clear pronunciation and speech were crucial (6% or 2 respondents, refer to figure 3) and they placed emphasis on receptiveness to feedback and showing respect to the speakers. This shows the importance of politeness in the cultures of the Malay and Chinese races.

The Chinese language (CL) preservice teachers’ self-assessment of their communication weaknesses involves linguistics, organization of message, voice projection and perception of listeners of their message. One of the CL preservice teachers claimed that she preferred to listen rather than talk. She felt that she was too lazy to think of a topic for conversation and was unable to organize the content of what she says. She felt she lacked practice in conversation, ‘don’t make enough time to communicate’. She thought she was ‘long winded’, cannot straight to the point’. Another of her classmates found that her communicative weakness had to do with not being able to inject life into her utterance by varying her pitch and tone. She thought her utterances were monotonous. She encountered problems in communication breakdown as she ‘speaks very fast in a conversation’. Therefore, ‘the message she(I) tried to bring across would be perceived wrongly’. In addition, she felt she had to ‘take note of her (my) voice projection’ as she speaks softly ‘that not everyone can hear her (me) clearly.’

Confidence in using the English language seems to be a prominent concern among these CL preservice teachers as English is not their first language. One of the CL preservice teachers attributed her rapid pace of speaking to her low confidence in speaking in English which was her second language. She was also used to ‘leading the conversation’and ‘didn’t give too much chance for the others to talk’. Her reason to race in her speech was probably due to her fear of not being able to respond appropriately when asked questions. This ‘lack of confidence in using English’ was echoed by another CL preservice teacher. One of her weaknesses was her árticulation’ as she had not ‘learnt IPA before’, so her ‘pronunciation of some words are not that accurate’. She also felt she did not possess ‘a large and growing vocabulary’ and ‘does not structure English sentences or summarize it very well’. She found that her messages were not well-organized and she found it difficult ‘to deliver her (my) idea or thought clearly and accurately in time’. She needed time to prepare before she spoke (she is obviously referring to public speaking) and she relied too heavily on her script.

The CL preservice teachers’ awareness of how their listeners might receive their message was reflected in the concern expressed by one class member. This class member perceived his main weakness as a lack of humour, describing humour as a ‘lubricant of communication’. He thought humour could help listeners to ‘feel more comfortable, happy and interesting’. He was afraid that people would find it boring to talk to him. In addition, he thought his message was detailed and comprehensive and listeners might not get the gist. He thought his ‘scope of knowledge’ was ‘narrow’ and he was unable to accomplish his communication aim as a result. This awareness of the listener’s perception was also echoed in other class members’ concern about weak voice, lack of appropriate body language and words used which did not accurately portray intended message.

The prominent weaknesses identified by the preservice teachers in the General Track (GT) had to do with the pace of speaking, voice volume and paralinguistics like eye contact. A number of them reflected that they spoke too fast, at the risk of the listeners not comprehending them.

With regards to non-verbal language, a number of the GT preservice teachers were aware that they failed to maintain eye contact and risk being interpreted as rude. One of them ascribed this lack of eye contact to the state of her self-esteem. She was also fearful that she was too emotional when communicating and believed that teachers should be calm and composed. Other paralinguistic weaknesses identified by this group of preservice teachers included failure to use body language effectively in communication and vary pitch and loudness when speaking (16%, or 6 respondents, refer to figure 3). One of them felt her problems lie in her posture and gestures. She had a habit of folding her arms or placing her arms on her hips when communicating. She was afraid this may convey aggressiveness and felt that as a teacher, she should not allow her body language to reveal her true emotions. In addition, one of the prominent concerns of this group of preservice teachers was the ability to project their voice when teaching (42%, or 15 respondents, refer to figure 3).

Many of this group of preservice teachers also reflected that they lapsed into the use of ‘Singlish’, a colloquial variety of English (26% or 9 respondents, refer to figure 3). One of them reflected that he used Singlish unintentionally in class. One preservice teacher was aware of the need to code-switch in appropriate situations. Another preservice teacher pointed out specifically to his use of fillers like ‘lah’, ‘meh’. These responses show the conflicts the preservice teachers face about the variety of English they should use in the classroom, and the effect on their professional image.

Only one preservice teacher in this group reflected that her weakness relates to articulation of words and mispronunciation leading to miscommunication. In contrast, this is the prominent concern for the CL preservice teachers. Another preservice teacher related that her weakness lies in the inability to find appropriate words to express what she wants to communicate while another felt that his problem lies in phrasing of words. Lastly, one preservice teacher confided to stuttering when nervous.

From the reflection of the preservice teachers’ journals, it can be deduced that their concerns with communication skills in teaching and communication with people in schools lie in the following areas: linguistic features such as pronunciation; paralinguistic features such as tone, register and pitch and the interpersonal aspects such as creating humour, smiling, nodding etc. They are also concerned with the appropriate variety to use in appropriate contexts whether it is Singaporean Standard English or the colloquial version, namely Singlish. Cornett-DeVito and Worley (2005) offered a definition that was useful in this study: ‘‘Instructional communication competence is the teacher instructor’s motivation, knowledge and skill to select, enact and evaluate effective and appropriate, verbal and nonverbal, interpersonal and instructional messages filtered by student-learners’ perceptions, resulting in cognitive, affective and behavioral student-learner development and reciprocal feedback’’ (p. 315).

The concern with using effective communication skills among the preservice teachers has to do with the dual role that teachers play: as role models of standard English, and as someone who builds rapport with the students. This correlates with the claim made by Jones and Fong (1999) that teachers see the importance of communication skills not only in classroom instruction, but also in creating interpersonal relationships with students.

The multilingual environment of Singapore complicates this perception of the teachers’ role as Singlish is seen as the more effective variety in building interpersonal relationship, while the Singapore Standard English, the more appropriate variety in classroom instruction. The Singaporean teacher is faced with the dilemma of projecting a professional self-image which they feel is maintained through the use of SSE and avoidance from the use of Singlish. They are also mindful that they are not impeding their students’ literacy skills by using Singlish in the classroom (Rudy, 2007). However, the teacher wants to build rapport with the students as well, which is made possible through the use of Singlish. These preservice teachers reached a solution for this dilemma by concluding that there is an appropriate time and context for these two varieties of English. Code-mixing became the answer to this situation. This dilemma in the choice of varieties of English is compounded by the awareness among the preservice teachers that their language use affects the language learning of their students. This is shown in their reflection journals in which they expressed that they were the role models of language use for their students. Therefore, choice of the variety of English has an impact of the listeners’ perception of the speakers and the language learning of the students. This issue is a prime concern of Singapore’s government, as seen in the large coverage of this issue in the media. In a newspaper report, a minister called for a collective effort, namely, from the media, family and schools, to raise the proficiency of English of the students. He was quoted as saying: ‘surveys by Ministry of Education and external agencies have shown that students are weaker in oral skills and lack the opportunities to use standard English.’ (The Straits Times Singapore, March 10, 2010).

The preservice teachers in both the General Track and Mother Tongue groups recognized the significance of the affective aspect of communication. Besides the use of non-verbal language like maintaining eye contact, nodding and smiling that develop positive interpersonal relationships between both parties, the preservice teachers recognized the vital role Singlish plays in building rapport with their students. In a study on award-winning teachers’ concept of effective communication skills, teachers describe effective communication skills as consisting of content knowledge accompanied with the communication of such knowledge in ways that engage students. Another teacher describes effective communication skills as the creation of ‘an engaging class culture; connecting with the person first, student second; being sensitive to student needs; showing them respect; creating an environment with an affective orientation; [and] packaging content meaningfully for long term learning.’ (p. 6, Worley, Titsworth, Cornett-DeVito, 2007). The preservice teachers in the present study were conscious of this need to build a positive classroom climate and the significant role of language use.

The act of teaching does not solely consist of course delivery and instruction. In engaging the students, the teacher may choose to use a colloquial variety that the students can identify with. In doing so, the teacher builds a bridge through establishing a common identity. This helps the students to develop a familiarity and bond with the teacher and subject that can make his/her learning more effective. In Worley, Titsworth, Worley, Cornett-DeVito (2007), this aspect of a teacher’s communication is described as ‘immediacy, relationships, and affect–for you’. To achieve this, the teacher may choose ‘to use appropriate slang to help students identify with you. But language needs to be appropriate to the relationship.’ (p. 9). In the case of Singapore, such an identity may be established through the use of Singlish, the variety of English that is close to the hearts of Singaporeans. This fact is reinforced by the findings in Rudy’s (2007) study that discovers that Singlish is a useful language for teachers to build rapport with their students.

It is in this creation of interpersonal relationships that the aspects of communication identified by the preservice teachers such as active listening, eye contact, humour and other paralinguistic cues find its place. In addition, communication is a two way process and the teacher needs to perceive and respond to students’ reaction to his/her communication. For this reason, the preservice teachers in this study expressed a concern about clarity of speech. This is a concern that all teachers share, namely, how students perceive their messages and respond to them. This reinforces the point made by Saunders and Mills (1999) that communication skills is important in to the teacher in classroom management, interaction with the class and pedagogy.

This aspect of clarity in communication is complicated by the existence of different languages and varieties of English in Singapore. Consequently, the teachers teaching mother tongue languages, whose first language is not English, struggles with the apprehension about the comprehensibility of their spoken English. This raises an issue concerning intercultural communication. In a multilingual and multicultural country like Singapore, there is obviously a need for people to develop strategies for learning and using English in an environment where multiple varieties of English exist (Author., Pathak, and Serwe, 2009). In addition, it necessitates an attitude of openness, a willingness to engage with people of other cultures, and skills of interpreting and relating to other cultures (Garrido, and Álvarez, 2006). In addition, the issue of language use in terms of choosing between SSE and Singlish should be evaluated in the light of the wider contexts of multilingualism, multiculturalism and the relation between language and identity.

In this study, the preservice teachers show audience awareness in their reflection that non-verbal communication like tone, pitch of voice and facial expressions in communicating the speaker’s attitude both towards the subject of the conversation and the listener. In the study by Worley, Titsworth, Worley, Cornett-DeVito, (2007), the award-winning teachers identify these aspects as the soft skills of communication, which they say consist of ‘motivation, use of verbal and non-verbal communication, the establishment of interpersonal relationships with students, and the establishment of a positive classroom climate.’ (p. 8). The preservice teachers in the Mother Tongue group emphasized politeness and were very conscious of their self-image. While the General Track group was conscious of their self-image, the Mother Tongue group was more concerned of the image they portrayed to their colleagues since they used English to communicate with their colleagues rather than students.

The study done by Worley, Titsworth, Worley, Cornett-DeVito (2007) reveals the importance of reflexivity of teachers. In their study, the award-winning teachers say they regularly reflect on their students’ responses to their communication and adapt their communication to their students. For this reason, the present study deemed it important to engage the preservice teachers to reflect on their communication skills. It would be interesting and important to study their perception of the effectiveness of their communication skills after they enter into the teaching service. This could be a study that follows the present research. The development of effective communication skills is one of the desired outcomes of initial teacher training in Singapore (Deng, 2004).

It is important, therefore, to carry out research on the importance of communication skills for teachers. Preservice teachers’ reflection of their communication strengths and weaknesses will ultimately have implications in their self-confidence when they stand in front of the class. In addition, the multilingual environment within and outside the classroom has an impact in the language choice and language use of teachers. Teachers face a dilemma in this language choice as they are concerned both with their professional image and implications on language learning of their students. This issue is complicated by the rampant use of Singlish, which carries a low status in society, but is at the same time an identity marker of Singaporeans. The results of this study have implications in course design of communication courses in teacher education programs, language policies of a country as well as policies about language pedagogy. A communication course for teachers in a multilingual society like Singapore should include sociolinguistic discussions of language choice and use. It should also include the effects of bilingualism on students’ learning of English.

More research, in particular, should be carried out in the dilemma and conflicts faced by teachers in a multilingual environment like Singapore, where different varieties of English also exist. This study has shown that there is a need to consider the struggles that preservice teachers teaching mother tongue languages face in using English, which is either their second or foreign language. Further studies can also be conducted on the intercultural communication of teachers in such multilingual environment and how respect, openness and adaptability are important in such multicultural contexts.

Alsagoff, L. (2007), Singlish: Negotiating Culture, Capital and Identity in V. Vaish, S. Gopinathan, and Y. Liu (eds). Language, Capital, Culture. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Author, 2009(details removed for peer review), Pathak, A. and Serwe, S.K., Modelling the English Learning Process of Foreign Students in Singapore: Thematic Analyses of Student Focus Groups, Humanising Language Learning, Year 11; Issue 4; August 2009.

old.hltmag.co.uk/aug09/mart01.htm

Calderhead, James and Robson, Maurice (1991). Images of teaching: Student teachers’ early conceptions of classroom practice. Teaching and Teacher Education Vol 7, No 1 pp1-8.

Cornett-DeVito, M. & Worley, D. W. (2005). A front row seat: A phenomenological investigation of students with learning disabilities. Communication Education, 54, 312–333.

Deng, Zongyi (2004) 'Beyond teacher training: Singaporean teacher preparation in the era of new educational initiatives', Teaching Education, 15: 2, 159 — 173.

Garrido, Cecilia and Álvarez, Inma(2006) 'Language teacher education for intercultural understanding', European Journal of Teacher Education, 29: 2, 163 — 179.

Goh, C., Perspectives on Spoken Grammar. ELT Journal Advance Access published March 10, 2009.

Farrell, T.S. and Tan K.K. S., Language Policy, Language Teachers’ Beliefs, and Classroom Practices. Applied Linguistics, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2007, pp. 381-403.

Johnson, K. (1994). The emerging beliefs and institutional practices of pre-service English as second language teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 10(4), 439-452.

Jones, J.F. and Fong, P.M. (2007). The impact of teachers’ beliefs and educational experiences on EFL classroom practices in secondary schools, Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 17, 27-47.

Kagan, D.M. Implications of Research on Teacher Belief. Educational Psychologist, 1992, Vol. 27. pp. 65-90.

Lee, Patty (1997). Collaborative practices for educators: Strategies for effective communication. Peytral Public, Minnesota.

McCarthy, M.R. and R. Carter (2001). Ten Criteria for a Spoken Grammar in E. Hinkel and S. Fotos (eds). New Perspectives on Grammar Teaching in Second Language Classrooms. Mahwah, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pratt, Daniel D. Conceptions of teaching. Adult Education Quarterly Vol.42, Number 4, Summer, 1992

Richards, J.C. (1998). Beyond Training. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rudy, R., Singlish in the School: An Impediment or a Resource? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2007.

Saunders, S. and Mill, M.A. (1999), The knowledge of communication skills of secondary graduate student teachers and their understanding of the relationship between communication skills and teaching. NZARE / AARE Conference Paper – Melbourne, Conference Paper Number MIL99660

Shapiro, B. L. A. (1991) Collaborative Approach to help novice science teachers reflect on changes in their construction of the role of the science teacher. Alberta Journal of Educational Research 37 pp119-132.

Tan, P.K.W. and Rubdy, R. (2008), Introduction in Tan, P.K.W. and Rani, R. (ed.), Language as Commodity. Global Structures, Local Marketplaces. London and N.Y: Continuum International Publishing Group. The Straits Times, Singapore (March 10, 2010), Moves to lift English proficiency by Leow Si Wan.

Timmis, I. (2002), Native-speaker Norms and International English: a Classroom View, ELT Journal Vol. 56, No. 3, pp. 240-9.

Worley D., Titsworth, S., Worley, D.W., Cornett-DeVito, M., Instructional Communication Competence: Lessons Learned from Award-Winning Teachers, Communication Studies, Vol. 58, No. 2, June 2007, pp. 207–222,

www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713721871

The Building Positive Group Dynamics course can be viewed here

The How to be a Teacher Trainer course can be viewed here

|