Concordancer Analysis, Description and Comparison of Language Produced by Learners and Native English Speakers

Nick Morley, Thailand

Nick Morley is currently working in Basra, Iraq but based in Bangkok, Thailand. Nick has taught in Asia since 2000 and has a long- term interest in helping learners to notice the language they use and discover how to improve it themselves. He also enjoys working with low- level teenage learners. Nick holds an MA TESOL and an M Ed (Applied Linguistics) and Trinity Licentiate Diploma in TESOL. E- mail: xyiq@yahoo.com

Skype: nick.morley111

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Aims

Rationale for the study

Methodology

Precautions taken with the evidence

Methods

Findings

Evaluation

Implications

References

A concordancing program assisted analysis of how 15 teenage Asian English language learners made progress with learning conditional language. Use of a concordancer program enabled comparison of learners’ texts with a larger native speaker sample. Most notable findings were that learners produced language more flexibly than their course book material models. However, leaners’ successful and creative production of the language taught, in this case use of conditional language, may not be rewarded by narrowly focused assessment rubrics. The discussion demonstrates how using the most basic concordancer functions can efficiently manage and analyse large quantities of learners’ written texts. A comparative 1,073,466 word native speaker corpus was used to make comparisons and contrasts between learner and native-speaker language use. Learners’ texts were collected from entries on their class blog after they wrote about future wishes to consolidate a series of communicative speaking activities. Also noted was how some areas of conditional language had significantly high error rates, which suggests additional attention is required to help learners notice them accrately.

Key words: conditional, concordancer, corpus, Thai, hypothesising

This small -scale study of conditional or hypothesising language produced by 15 teenage Thai language learners (nine females and six males) used a concordancing program to explore how the learners were using target language and provide a descriptive linguistic analysis of their conditional/hypothesising language. This was carried out after they participated in learning the second conditional to talk about the unreal future, and wish for the unreal present when compared with native speaker texts in the OU – BNC Fiction corpus (2010).

Most notable was that the learners used the target language more flexibly and creatively than the model provided by their teaching materials, Breakthrough success with English 3 Student book, by Craven (2008). However, this flexible use meant that rigid or standard assessment rubrics would not recognise and reward their efforts.

Using a freely available online concordancing program to support analysis of the learners’ texts revealed a surprising 100 per cent errors with some aspects of conditional language usage. This significantly high error rate indicates the need for extra attention and for focused pre -teaching with this learner group. The study compared a small 3,361 word sample of the learners’ texts from their class blog, with the 1,073,466 word OU – BNC Fiction corpus native speaker sample.

For those who have not used a concordance before, this article also illustrates how using the its most basic non-specialist functions enables analysis of large samples of learners’ texts in quick, efficient and informative ways. This aspect is growing in relevance as there are now collections of Asian English language learners’ text samples available online which can be used either for comparison with specific learner groups or for analysis of how, for example, Japanese language learners produce the past tense. Using language analysis programmes is becoming increasingly relevant as learners can now often produce soft copy texts while completing a variety of motivating tasks, such as, blogging.

The classroom based research project uses descriptive linguistic analysis to describe how Thai EFL learners realised the unreal future and present after learning the second conditional and wish. The aim was to explore evidence in a core set of six sample texts, averaging 224 words each, which had been rated the two highest, median and lowest scoring during holistic continuous assessment of the fifteen learner texts. The original sample size of 15 texts was reduced to make manual analysis manageable and to maintain a representation of the spread of abilities within the group. Using these three -tiered samples (highest, median and lowest scoring) aimed to reduce possibilities of bias. The project then compared learners’ text samples with native speaker usage in the OU – BNC Fiction corpus.

Further sub aims were: to discover how Thai learners hypothesized after using their course materials, Breakthrough success with English 3 Student book, Craven (2008). For comparisons with the native speaker corpus the core set of six texts was extended to the class set of 15, which produced a specialised learner corpus of 3,361 words. The texts were produced when authors blogged about a friend’s present or future wishes. Finally, contrastive analysis of frequent errors aimed to identify potentially problematic differences between Thai and English when differences between languages result in production difficulties, Mayor (2006).

Demands placed on learners

Understanding how learners produce more complex language, such as conditionals, is important because they are progressing along a continuum, moving away from primarily concrete and present time oriented language towards abstract usage through expressing unreal or hypothetical situations in the future or present. This shift seems counter – intuitive as learners are asked to move from the present, using will – for decisions about future plans, going to – to report firm plans and want – to express desired future outcomes. They are then asked to change to using the past to express unreal or hypothetical future or present events, as these attempts show: “She’d like to travel around the world if she had an opportunity.” “She wish she was “Albert Einstine. ”Note: errors in original samples

Defining the target language

The learners were beginning to understand what Biber et al (2009) describe as second conditional clauses, which also include expressions of epistemic modality, (an expression of a writer’s/ speaker’s judgement about the likelihood of what he or she is saying). The pragmatic function (how language is used in context to perform social acts) is to express a present/future unreal/hypothetical condition likely/ unlikely to be fulfilled, Biber et al (2009:457). For example, (from learners’ texts)

“If she had more money, she’d buy cartoons.”

Condition: If + subject + finite: simple past = unreal condition now or future

Result: Modal finite: would + finite: present = real/unreal result

The learners’ course materials also introduced wish at the same time, defining its usage as:

“We use I wish + simple past to talk about a present situation we would like to be different: I wish I wish we didn’t have so much homework.” Craven (2008:111)

Why the study is significant for its context

The learners had a limited amount of lesson time available; therefore, identifying tendencies towards errors would help with presenting conditional language to Thai speakers. Conversely, in areas where usage is relatively unproblematic, coverage can be reduced.

Evaluating the group’s language learning needs

While the learners performed well on the course book’s controlled activities designed to demonstrate and practice language awareness of conditional language, their level of performance was not being transferred to free speaking practice in class. This lack of transfer was noticeable when it came to writing up an interview with about a friend’s future wishes on the class blog. This gap between achievements on controlled activities and performance on a free writing task is significant, as the learners had carried out a considerable amount of pre –writing preparation. Their sample texts provided a brief snapshot of how they produced the target language after the following preparatory class activities: paired information exchanges built up over several lessons involving interviewing about the future, paired drafting and editing, and finally blogging about a friend. For the teacher, reviewing their writing revealed significant difficulties with conditional and wish clause production.

Using Corpus based analysis

One my main concerns as the teacher was whether the course input really reflects how native speakers use conditional language as described by Biber et al (2009) and Coffin et al (2009). If course materials do not reflect natural language use, learners are potentially disadvantaged because assessments often focus on learners’ production of full forms, in a way intended to “show you know”. In practice, this would favour repetitive or stilted production, unrepresentative of native speaker usage, Thornbury and Slade (2006). Therefore, a corpus-based exploration of native speaker texts was undertaken to provide evidence of a wider range of appropriate usage.

As the learners’ texts were written on their class blog, their writing was downloaded to create a specialised learner corpus, Mayor (2006). This was a very straightforward process involving copying their blog texts to a word document and saving this as a text file to be processed by the concordancer. Analysis can be carried out with concordancing software freely available online which is simple to download and install.

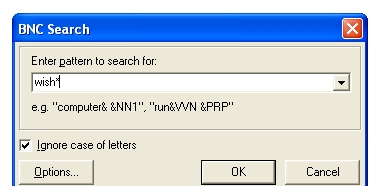

The aim for using a concordancer was to efficiently carry out heuristic or exploratory searches of a large sample of learners’ blogs, (3,361 words). It was possible to enter a search term, such as wish and the concordancer would produce all instances of wish with its surrounding co-text, as below:

Wish samples from a concordance search of the learners’ texts

“....be my good friend. / She wish she was smarter Her friend...”

“...them about a knowledge. /She wish she could have a better little...”

“...in her math book./She wish she wasn’t gets a bad grade...”

“...the time machine. //3. He wish he was the richest man in...

Why a Concordancer was helpful

Being able to view the whole class set of sentences using wish at a glance, produced an immediate picture of its use, such as, “He wish that...” or “He wishes that...” Presenting learners with a screen shot helped to demonstrate the extent of errors. This evidence also helped learners to examine samples of the surrounding text in order to see their errors in context, as well as their most common forms of use, such as; personal pronoun + wish + (either) personal pronoun (or) that + could...: “He wishes he could…”

How a native speaker comparative corpus helped

The main point was making sure that like with like comparisons were being made to ensure accuracy. For example, a native speaker corpus sample from academic writing or medical texts would not feature many conditional language uses similar to the learners’ texts. Therefore, the OU –BNC Fiction corpus was selected as a comparison tool, discussed by Hewings (2006), because it was most representative of the learners’ text style as they were encouraged to be creative with language use, for example, “...because If he can do every thing by him self he can do every thing he want. He will make the time machine.”

A further point regarding choosing the OU –BNC Fiction corpus is that learners’ texts were based on conversation and reporting and therefore based on speech which is well represented in fictional dialogues. Fiction writing is also rich in verbs which comprise conditional forms, Biber and Conrad (2004), and fiction writing also contains comments on how characters wished situations to be, such as; “He wished he could be like Martin. ”OU – BNC Fiction corpus (2010) search for wish*Note: wish* denotes a wildcard search term, which will return any form after wish, such as, wished or wishing.

Learners carried out pre -writing and drafting stages, therefore, this made the OU –BNC Speech corpus a less suitable choice for comparison because speech takes place in real time and is therefore unplanned.

The learners’ writing samples and Concordancer

Learner language samples comprised of an untagged (items were not coded as verbs, nouns etc) special purpose Thai EFL learner corpus complied to focus on a particular variety of language Tognini – Bonelli (2004). This special purpose Thai EFL learner corpus was not extensive, it consisted of 15 texts totalling 3,361 words, six representative samples were selected for manual qualitative analysis, and average sample length was 224 words. The sample has a synchronic aspect, a corpus representing language at a particular point in time, as it was taken at a particular stage in the learners’ developmental progress. This corpus is definitely small when considering the vast corpora of tens of millions of words or more in use today. However, it still has relevance as the language tasks were designed to elicit frequent use of conditional language, and this is considered more important than a larger but unfocused sample, Hewings (2006:97).

A comparative corpus (sets of texts in two or more languages), discussed by Hewings (2006), was provided by the tagged (all the parts of speech are coded to enable searches for specific items, such as, articles) OU – BNC Fiction corpus, which is comprised of 1,073,466 words. This corpus was analysed for frequency of hypothetical/conditional language samples by searching with the concordance program MonoConc Pro 2.1. This was because corpus analysis is the logical choice when looking for frequencies of language use, (Hewings 2006:9)

Screenshot of concordance programme in use - Using search terms with MonoConcProgramme

This approach and methodology was necessarily top down, beginning with a defined linguistic pattern and drawing on corpus evidence for comparison, Tognini- Bonelli (2004:17).

Adapting the methodology

Once analysis had begun, it became apparent that the original sample of 15 whole class learner texts was too large for timely and efficient manual analysis. Therefore, the whole class set of 15 texts was reduced to a representative sample of six. A Similar problem occurred with the OU – BNC Fiction comparative corpus because the sheer extent, variety and complexity of language expressing an unreal present/future made isolating and categorising samples difficult. For instance, manually thinning (removing any examples not representing the search term by deleting them) matches for ‘d (would), such as, “I’d (would) love to go...”(expressing a future wish) to remove unwanted instances of I’d, such as, “I’d (had) better go,” (expressing obligation/modality) from 1,299 matches to produce 469 native speaker samples expressing a hypothetical condition took over four hours. After thinning out examples of ‘d, which were not fulfilling a hypothetical function, a more accurate range of comparisons was possible.

Concordance line samples, the first 5 lines of a search for ‘d after thinning from 1,299 to 469 matches.

- ... if you come mob-handed, but I've a feeling in my water about this one. I[[[['d]]]] like to have a proper team together right from the start.

- ... help with young Wilson? I could ring up a colleague in New York.' 'She[[[['d]]]] rather fix it herself if she can, sir, I do know that. But thank you.' ...

- ... a perfectly respectable trade,' she added conscientiously. 'I don't mind lobbyists, I[[[['d]]]] just rather they called themselves by their proper name as they do in Washington, rather than ...

- ... able to undercut them in the market.' 'So Miss Morgan was making sure you[[[['d]]]] understood all that? I see where it annoyed you.' Francesca was not amused. 'Yes ...

- ... em to have felt, nonetheless, that it was worth a lunch.' She paused. 'I[[[['d]]]] have to say that given the change of government they ought to have a very good ...

The data sets

All data was normalized, this was done by converting it to percentages to avoid distortion owing to different corpora sizes; percentaging gives a different perspective on data (Open University 2007:153). This step allowed relative comparisons to be made, for example, a 10 per cent occurrence of wish in the 3,361 word learner text corpus would be the equivalent of a 10 per cent occurrence in the 1,073,466 word OU – BNC Fiction corpus. For example, a search for wish in the 3,361 world learner corpus returned 45 hits (citations or occurrences), therefore 45/ 3,361x 100 = 1.33%.

Variables

Variables it was possible to control for: controlled variables, which are those which are possible to hold constant, during the process and were; speaking to writing task stages, all the learners followed the same stages, learner level, all learners were at the same language level, and the same learner pairs completed all the pre-writing and writing stagers together.

The independent variable, which is a variable manipulated for the purpose of research, was the task design eliciting conditional language.

The dependent variable, which is a feature depending on other factors, such as test scores and the amount of revision done before the test, was the conditional language and its variance from the pedagogical grammar and OU – BNC Fiction corpus.

Avoiding bias

Concordance search results were manually checked to ensure relevance and avoid bias in word frequency lists. This manual checking was necessary because would, for example, can also be used to make offers as well as form conditionals, O’Halloran (2006). If overlooked, this dual function is liable to produce misleading frequency counts.

Data preparation

While using the class blog provided readymade and accessible soft copies it was still necessary to copy and paste the blog texts onto a word document in order to clean the data (the learners texts had spelling errors which were corrected to ensure the concordancer would be able to locate all occurrences of the search item) before saving them as plain text files for the concordancer to process. Data cleaning was necessary to enhance reliability by correcting spelling, this ensured accurate searches for frequency or collocation were possible. Attention to accuracy is important for such a small sample, as small inaccuracies or omissions would be greatly magnified and distort the results, Koller and Mautner (2004:219). The following data sets were converted to concordance files by saving them as plain text files; one class set of 15 texts for broad comparisons and a representative sample of six texts for corpus and manual analysis.

Manual analysis of learner texts

Sample texts were analysed to ascertain how the learners produced conditional language in terms of comparing frequencies for non -native speaker use. Quantitative data was compared for type and frequencies usage as well as predominant errors. The concordancer programme was used to research native speaker hypothesizing in the OU – BNC Fiction corpus and to describe examples of the range of native speaker use. Findings from the learners’ samples and the OU – BNC Fiction corpus were compared.

The study has correlational and comparative elements as the data sets were compared to explore relationships between learners’ and native speakers’ conditional language, Mayor (2006). Out of necessity the learners were drawn from a convenience sample (these were simply the most readily available and willing participants and were therefore not selected randomly). Therefore, the findings cannot be claimed to be representative of the wider student population, Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2005).

How learners used conditional language

Table 1: Extent of conditional language used and percentage of errors six authors made Table one below, represents the extent of conditional language six of the learners produced.

| Hypothetical language |

Total |

Percentage

of all forms

|

Percent correct |

Percent

errors

|

| All forms of hypothetical language produced |

47 |

100 |

38.3 |

61.7 |

| Second conditional |

14 |

29.8 |

7.1 |

92.9 |

| Second conditional, if clause in second position |

8 |

17 |

37.6 |

62.6 |

| Subject + wish |

8 |

17 |

0 |

100 |

| First conditional to express something as possible |

1 |

2.1 |

100 |

0 |

If clause dropped when context established, Coffin et al (2009:177), and uses of:

- I/she/he think(s) + will

2) She/he thinks +that +verb –ing

- use of subject + will + present simple

- Use of if clause only once context was established. Omission of result clause

- Use of logical connector because for condition and will for result

- Use of a temporal adjunct, e.g.

then+ subject + want + simple present to express prediction and desire

when + subject + has/have for condition with will for result

|

13 |

27.7 |

84.6 |

15.4 |

| Non- prescribed use of wants to indicate hypothetical future condition |

1 |

2.1 |

0 |

100 |

| Blend: use of present simple in the condition and would in the result clause |

1 |

2.1 |

100 |

0 |

| Use of think + temporal adjunct when + present simple with will for intent/future. Think is being used as interpersonal grammatical metaphor * |

1 |

2.1 |

100 |

0 |

* Interpersonal grammatical metaphor (something is equivalent to another thing which is not usually associated with it)

Table 1 above illustrates how analysis of the 1,431 word representative sample from six learners revealed the following: hypothesising occurred 47 times in all. This frequency is a result of task design; therefore, frequency comparisons with naturally occurring data cannot be made. Error rates, even after prolonged controlled practice, drafting and peer editing, errors rates appeared to be high at 61.7 per cent. This high percentage of errors after prolonged practice indicates a potentially problematic language area. The second conditional, if condition clause followed by would/wouldn’t result clauses were preferred to using the if clause in second position, at 29.8 and 17 per cent respectively. However, using the if clause in the initial position appears more problematic, resulting in 30.3 per cent more errors. When learners used wish to discuss a present situation that the person would prefer to be different, they produced a significant 100 per cent error rate.

However, what was surprising was the range and flexibility with which learners chose to hypothesise. This variety was explored with the concordancer and the search results confirmed by manual analysis. Most notable was, that once the hypothetical context was established as ongoing, learners dropped the use of the if clause, discussed by Coffin et al (2009:177). This native speaker like production produced the following patterns:

- I/she/he think(s) + will

- She/he thinks +that +verb –ing

- Use of subject + will + present simple

- Use of if clause only. Omission of result clause

- Use of logical connector because for condition and will for result

- Use of temporal adjuncts, e.g.

then + subject + want + simple present to express prediction and desire

“...and when he have a lot of money he...”

when + subject + has/have for condition with will/would for result

“...and when he have a lot of money he would buy...”

These forms are significant because course assessment materials for spoken and written English focus on scoring full production, and would not therefore reward appropriate use of ellipsis, where elements of a clause or phrase are not produced, such as; speaker A: “I’ve got a lot of them.” Speaker B: “No you haven’t .....” Furthermore, the learners’ pedagogic grammar resource did not demonstrate this.

Further non –prescribed uses appeared, such as, wants, when the context was established, such as;

“She wants to be male because she wants to go to USA with her brothers.”

Also evident were blended conditionals with the present simple in the if clause and would in the result clause. Interpersonal grammatical metaphor appeared in the use of think + temporal adjunct when + present simple with will for intent/future;

“She think when she clever she can do…”

How learners used ‘Wish’,

Despite exposure to and practice with using wish through course materials, there was a puzzling one hundred per cent error rate with the written form. Learners frequently attempted to use wish/es and a concordance search for wish in the whole set of 15 texts returned 34 matches, which after thinning to leave pronoun +’ wish/es showed 18 matches or 0.53 per cent of the total texts. This occurrence is more frequent than results from searching the OU – BNC Fiction corpus and is not significant because task design would have elicited hypothesizing language from the small sample of learner texts. Searching the OU – BNC Fiction corpus with the search term wishes&*VVZ , (&*VVZ as the search term for the –s form of all lexical verbs. The term * is a suitable search term and choice of wildcard as it will bring up all words which are verbs in the same way that * &N* will extract all words which are nouns) returned 13 matches. Only two of these strings, a single line of text returned from a concordance search, such as, “…her feel happier because she think that eating and buying will…” matched learners’ use of she/he wishes, and on closer analysis of the co-text (the text surrounding a particular item) neither carried the same function of wishing that the present or future were different. However, subsequent searching with wished&*VVD (the search term *VVD was used to return samples of past tense usage) returned 99 matches, which after thinning to leave pronoun + wished, produced 73 matches or 0.006 per cent of the 1,073,466 word OU – BNC Fiction corpus. However, this result reflects a methodological issue with the OU – BNC Fiction corpus because fictional narratives have a strong tendency to take place in the historical present (the historical or dramatic present is a literary device used when the present tense narrates past events), Coffin et al (2009:142).

How learners used ‘think’

Blog authors showed their ability to use think very creatively in projecting clauses (the main clause that introduces a report or quote, such as, ‘The Prime minister announced today,…), for example:

She/he thinks +that +verb –ing to express likelihood of an event occurring:

“She thinks that eating...”

Use of think + temporal adjunct when + present simple to express a condition with will for future result:

“She think when she clever she can do any jobs and many company will want she to work together.”

There are two very important points to note here; firstly, the authors have, without instruction, omitted the initial if clause when context was established. Secondly, they used interpersonal grammatical metaphors via the mental process verb think to modalise/hypothesize, Coffin et al (2009:366). A mental process verb construes processes, such as thinking and sensing, which takes place mentally, such as, “I don’t know the answer.”

How learners used the Second Conditional

Punctuation clearly proved problematic as the learners omitted use of a comma between condition and result clauses in 85.7 percent of the whole class sample.

How learners produced modality

Table two below shows how learners produced modality as they hypothesized by using the following modals and semi modals with these frequencies.

Table 2: Learners’ choices of modality to produce hypothetical language

| Modal |

Frequency |

Modal |

Frequency |

| 1. will |

46 |

6. might |

0 |

| 2. can |

40 |

7. may |

0 |

| 3. would |

32 |

8. must |

0 |

| 4. have (in hypothetical sentences) |

27 |

9. should |

0 |

| 5. could |

13 |

10. need |

0 |

| Totals: 158 matches in a 3,361 word corpus which equals 4.7 per cent |

Searching the OU – BNC Fiction corpus with personal pronoun + modal finite, He would search term: *&PNP* &*VM0, returned a 0.93 per cent occurrence. This 0.93 per cent usage was far exceeded by the learners’ 3.77 per cent production. Again, significance is unlikely because task design elicited hypothetical language use, which includes modality. However, results like this, where there is an over-production of a target form, could be interpreted positively when evaluating a language task’s design and effectiveness, and is a potentially fruitful area for further investigation.

What was achieved?

From the perspective of an EFL teacher working with Thai learners the project demonstrated the need for far more evaluation of language demands learners face. This evaluation also indicates potential benefits from adjusting teaching strategies to increase the amount of pre –teaching for potentially challenging language points.

Most noteworthy however, was how the evidence illustrated gaps between the learners’ range of performance when hypothesising and how they are assessed. For example, the flexibility and range of their hypothesising went beyond the course materials’ input model. This broader range of language use indicates a need for a more informed and broader view of language in use to supplement the learners’ pedagogical grammar.

From a professional development perspective, learning and trying out the basic functions of a concordancer to analyse large samples of learners’ texts has meant being able to instantly look through thousands of words and get visual feedback showing exactly how the learners are working. This feedback from concordance searches showed what learners were doing well and common errors. An additional advantage came from using a comparative corpus to illustrate native speaker norms,which were outside of the range of the course materials. Further to this, and relating to other teaching contexts, there are freely available online corpora representing various learner groups, such as Japanese learners.

Suggestions for further investigation

There were five areas of learner language, which raised more questions which could be explored in more detail.

- The high frequency of errors (100 per cent) with the use of wish, such as;

“She wish she wasn’t a human.”

- The omission of commas between condition and result clauses, which occurred in a significantly high (85.7 per cent) proportion of the sample.

- The frequency with which learners dropped the use of if clauses once context was established in 27.7 per cent of all hypothesising, for example;

“...and when he have a lot of money he will buy the school to change the rules.”

- Use of the temporal adjunct when + subject + has/have for condition with will for result.

“...and when he have a lot of money he will...”

- The extent that the learners’ language differed from the pedagogical grammar’s input model but was able to achieve the same function affectively.

Regarding the learners’ context, the main implication is that the language they used successfully to fulfil hypothesising functions might be unrewarded. Lack of reward would be due to assessment and task assessment rubrics which demand full form production of the target form rather than language such as, ellipsis of the if clause when context is established or the use of I think... This narrow assessment focus favours a more stilted type of production unrepresentative of native speaker usage, Thornbury and Slade (2006). Addressing this situation requires teachers to be more informed and flexible when assessing learners’ language in order to give full credit for their attempts at language use.

Regarding the target language, although this was a very small scale study, the significant number of errors with using wish and omitting the comma between condition and result clauses indicates that these areas might be worthy of more attention in the pre-teaching stage with future Thai speaking learner groups.

Conclusions on concordancer assisted analysis

Manual analysis of learners’ texts was enhanced considerably by using the most basic functions of a concordancer feely available online (Simple Concordance Program 4.09 (build16) downloaded June 2010). Concordancing revealed a more about how the learners were progressing with the target language than manually sorting through their texts could in the same amount of time. For example, it was possible to search and analyse whole class sets of writing to see how learners were using specific items, such as, wish.

Samples from searches for wish.

“...be my good friend. / She wish she was smarter Her friend...”

“...hem about a knowledge. /She wish she could have a better little...”

“...in her math book./She wish she wasn’t gets a bad grade...”

“...the time machine. //3. He wish he was the richest man in...”

“...don’t have a problems.//6. He wish He wasn’t have any accident...”

“...can’t talk to anyone.//4.He wish he could wish anything he...”

“ ...anyone.//4.He wish he could wish anything he want and no limits...”

“...and no limits. If He can wish anytime his first wish is...”

It was possible to see how the whole class were using modals in the condition and result clauses.

Sample from searches for could

“ ...a knowledge. /She wish she could have a better little brother...”

“...He would feel upset if could not talk with his friends...”

“...would feel upset if he couldn’t chat with his friends...”

“...he will feel lonely when he couldn’t chat with his friends...”

“...to anyone.//4.He wish he could wish anything he want and...”

This aspect of searching a corpus is a useful tool as searches revealed how frequently modals were used, such as, thirty-two occurrences of would and thirteen occurrences of could.

These results were retrieved from a 634 word list of different words and how frequently they were used.

The main point with this type of frequency search is that it can also be used to follow up on vocabulary teaching, to look for evidence of new items being produced and how frequently they are used in comparison with alternatives. This also provides evidence of the range of learners’ vocabulary. For example, there are less common of more specialist items in the learners’ corpus, such as, infer, pharaohs, linen and perfectionist. There are also methods, beyond the scope of this discussion, for calculating lexical density, to find how rich the texts are in vocabulary.

Finally, as more learners are able to produce soft copies of their writing, whether on a class blog or more formally on writing projects, using basic concordancer functions can shed new light on how they are performing.

Biber. D., Conrad. S., and Leech, G.(2009). Longman student grammar of spoken and written English. Harlow, England: Longman.

Coffin, C., Donohue, J. and North S. (2009). Exploring English grammar from formal to functional. Oxford, England: Routledge.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. and Morrison, K. (2005).Research methods in education (5th ed). London, England: Routledge Falmer.

Craven. M. (2008). Breakthrough success with English 3: Student book. Tokyo, Japan: Macmillan Language House Ltd.

Hewings, A. (2006). Data collection for lexicogrammatical research. In A. Hewings (Ed.), Getting down to it: undertaking research. Milton Keynes, England: The Open University.

Koller, V, and Mautner, G. (2004). Computer applications in critical discourse analysis. In C.Coffin, A. Hewings and K. O’Halloran (Eds.), Applying English grammar, functional and corpus approaches. Milton Keynes, England: The Open University.

Mayor, B. (2006). Putting grammar into translation. In B.Mayor, (Ed), Applications: Putting grammar into professional practice. Milton Keynes, England: The Open University.

O’Halloran, K.A. (2006). Positioning and persuading. In K.A. O’Halloran (Ed), Getting inside English: interpreting texts. Milton Keynes, England: The Open University.

Open University (2007)E891 Educational enquiry (2007) study guide. Prepared for The Open University by Martin Hamersley. Milton Keynes, England: The Open University.

Open University – BNC Fiction corpus (2010), supplied with course E303, 2010 presentation. Milton Keynes, England: The Open University.

Simple Concordance Program 4.09 (build16) June 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010 from

http://simple-concordance-program.software.informer.com/

Thornbury, S. and Slade, D. (2006). Conversation from description to pedagogy. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Tognini- Bonelli, E. (2004). Working with corpora: Issues and insights. In C.Coffin, A. Hewings and K.A. O’Halloran (Eds.), Applying English grammar, functional and corpus approaches. Milton Keynes, England: The Open University.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|