Korean EFL Students’ Three Major Vocabulary Learning Strategies

Seong Man Park, Canada

Seong Man Park received his PhD in Second Language Education from McGill University, Canada, in 2010. He has been teaching both English and Korean to Korean international students and to Korean immigrant secondary and college students in the Korean language school at the Hosanna church in Montreal, Canada since 2004. He is interested in helping Korean students for their effective English learning as a major foreign language in Korea. E-mail: seong.m.park@mail.mcgill.ca

Menu

Introduction

A review of literature

1. Word form analysis (affixes and word roots)

2. Guessing the meaning of new words in the context

3. Bilingual dictionary use (pocket electronic dictionary)

The Study

Method

1. Participants

2. Material

3. Procedures

Results

Conclusion

References

Appendix A

The acquisition of vocabulary has been one of the most important and dynamic areas in recent second language (L2) acquisition research (Lightbown & Spada, 2006). Along with the rapid growth of interest in vocabulary acquisition research, a lot of research has been conducted in the field of L2 vocabulary acquisition in the last few decades (e.g., Schmitt, 1997; Lightbown & Spada, 2006). However, most research has been done in the field of instruction of L2 vocabulary neglecting the importance of vocabulary learning strategies (e.g., Schmitt, 1997; Park, 2001). Although there has been some research in the area of vocabulary learning strategies, they did not seem to attract any noticeable attention due to the lack of comprehensive research in this field (Schmitt, 1997). For most L2 learners, the importance of vocabulary learning strategies seems very clear in order to enhance their vocabulary knowledge depending on their different situations and contexts (Chin, 1999).

In this regard, this paper examines the most effective strategies in learners’ L2 learning, English as an L2 in particular, through a review of literature on the effects of L2 learning strategies and through a small pilot study regarding Korean EFL students’ three major English vocabulary learning strategies (i.e., word form analysis, guessing the meaning of new words from the context, and dictionary use). With regard to the above strategies, Chin (1999) claims that word form analysis, guessing the meaning of new words from the context, and dictionary use are traditional techniques which have been widely used and employed in L2 classrooms. These strategies are also commonly used in Korea (i.e., Republic of Korea). Thus, literature on these three strategies will be reviewed first and then a small experiment using these strategies will be explained in this paper.

Learning English vocabulary through word form analysis has been perceived as a useful way for Korean EFL learners (Park, 2001). In order to find out the relationship between affix and word size, Schmitt and Meara (1997) conducted an empirical study with 95 Japanese EFL students. The results reveal that “there were weaker, but still significant, correlations between receptive derivative suffix knowledge and vocabulary size” (Schmitt & Meara, 1997, p. 30). These results show that there are interrelationships between affix and vocabulary size in L2 learning and the amount of suffix knowledge can enhance learners’ overall vocabulary size with the easy access to a new word. However, they dealt with only suffixes without including prefixes and word roots in their study. Thus, their results are limited only to the relationships between a verb and its permissible suffixes. Mochizuki and Aizawa (2000) also claim that affix knowledge plays an important role in enhancing and facilitating L2 learners’ vocabulary knowledge. They investigated the relationship between learners’ vocabulary size and their affix knowledge with 403 Japanese high-school and university students. The results show that the amount of prefixes and suffixes knowledge is positively correlated with the amount of learners’ L2 vocabulary size. These results show that learners’ affix knowledge develops along with the development of their vocabulary knowledge. With regard to the use of affix knowledge in learning L2 vocabulary, Mochizuki and Aizawa (2000) also express the view that “the lexical meaning of a prefix and the syntactic role of a suffix” (p. 302) can facilitate the development and increase of learners vocabulary size.

In spite of the above advantages using affix knowledge in learners’ vocabulary development in their L2 learning, some scholars (e.g., Clarke & Nation, 1980; Chin, 1999) argue that there are also disadvantages in using this strategy. Regarding the misuse of this strategy, Chin (1999) warns that word form analysis should not be appropriate for low level students due to the fact that they might make a mistake caused by wrong guessing solely based on form analysis without considering the meaning of the word in the context. This idea shows that low level learners may be under disadvantages with this strategy, since they may not be able to integrate the meaning guessed from analyzing a word form into the contextual meaning of the word. In addition, Chin also warns that teachers should not teach students affixes apart from the relevant contexts, since learners are likely to rely on word form analysis instead of using the context to guess the meaning of a new word. Concerning the disadvantages of using word form analysis, Clarke and Nation (1980) provided two main reasons. First, they argue that the use of word form analysis may make learners guess the meaning of a word too quickly even before they consider the role of the word within the context. Second, they mentions that some affixes and word roots cannot be easily analyzed and broken into parts because they have more than one meaning, since only “25-30% of the vocabulary above the 3,000 word level can be broken into prefixes, roots, and suffixes” (Clarke & Nation, 1980, p. 215). However, notwithstanding the disadvantages mentioned above, Clarke and Nation (1980) also mention that the ratio of the advantages to disadvantages of word form analysis strategy is becoming identical in L2 vocabulary learning. Overall, the above review on word form analysis for learners’ vocabulary learning seems to suggest that word form analysis in isolation may not be the most effective strategy in L2 vocabulary learning.

With regard to the importance of context in L2 vocabulary learning, Nagy (1997) mentions that L2 learners may have difficulties in using context due to their low level of L2 proficiency. Chin (1999) also claims that successful learning of L2 vocabulary through context should be based on learners’ high level of L2 proficiency due to the correlation between two factors. Concerning Korean EFL students’ vocabulary learning strategies, Park (2001) conducted a survey with 600 Korean participants who have different academic backgrounds from elementary to college students. The results show that Korean learners of English widely use guessing strategy regardless of their age differences. But the one thing to be noted here is that even elementary school students are actively using guessing strategy (Park, 2001). This result is against the general notion that the ability to guess the meaning of a new word through the context is positively correlated with learners’ level of L2 proficiency. However, this result can be attributed to the promotion of communicative approach in English education in Korea. According to Schmitt (1997), the use of guessing strategy through context has been encouraged, because this strategy has been regarded as the most effective strategy with “the communicative approach than others” (p. 209). In fact, the adoption of communicative English language education introduces big changes in the area of English language teaching in Korea. The major change can be found in the length of contexts in the university entrance examination in Korea. The length of contexts in this test has been getting longer with the introduction of communicative approach. Thus, learners may not rely on the traditional word form analysis in this situation due to the lack of time to understand the whole text within the very limited time. In this respect, Coady (1997) suggests that EFL teachers should teach learners, beginners in particular, a list of highly frequent words so that “at least 3,000 word families” can be acquired for their independent vocabulary learning (p. 235). With regard to the amount of vocabulary knowledge for using guessing strategy, Clarke and Nation (1980) mention that around 3,000 words would be required for second language learners to guess 60-70% of the new words in the given context (p. 212). Nagy (1997) also claims that a certain level of L2 vocabulary proficiency should be acquired before learners can correctly guess the meaning of a new word from the context, since the knowledge of the words around a new word is very important to guess the meaning of the new word in the context.

Overall, there are some values to use guessing strategy in L2 vocabulary learning (Clarke & Nation, 1980). The first main value is that guessing strategy can make learners learn vocabulary by themselves without teachers’ assistance through extensive reading. The second value is that learners can save time and continue reading without interference, because they do not have to refer to a dictionary through guessing strategy while they are reading.

According to Park (2001), Korean learners of English depend too much on the use of bilingual dictionary especially in the stage of discovering the meaning of a new word regardless of different age groups. Concerning this issue, Tang (1997) analyzed Chinese students’ use of the pocket bilingual electronic dictionaries in the ESL classroom in Canada. The results show that the excessive use of dictionaries might deprive L2 learners of the chances to guess or predict the meanings of new words through context. In addition, the excessive use of dictionaries might hinder the flow of writing and reading and might provide numerous vague definitions per word. She also argues that dictionary look-up strategy may not be effective for making learners retain the meaning of the words they find in the dictionary. Pocket electronic dictionaries, in particular, provide learners with definitions too quickly without learners’ any efforts. Nevertheless, the result shows that the use of pocket electronic dictionaries is getting popular for L2 learners (Tang, 1997).

However, it is also obvious that the use of a bilingual dictionary is very useful in L2 vocabulary learning. The main strength of the bilingual dictionaries is the possibility to enable learners to facilitate their individual learning, since the bilingual dictionaries “can serve a bridging purpose” (Tang, 1997, p. 56) between two different languages and the use of dictionaries might be an efficient way of developing L2 vocabulary if learners are provided with the proper guidance. Chin (1999) also suggests that dictionaries should be used “to verify their educated guesses about the meanings of unknown words disclosed from context or word form analysis” (p. 3).

So far, literature on three major L2 vocabulary learning strategies has been reviewed. In this section, a small empirical study is explained in order to show how these three strategies work for 6 Korean students.

This study has 6 Korean student participants who were in the age range of 13-16. They were in elementary schools (i.e., 5 students) and in a junior high school (i.e., 1 student). The participants were placed randomly into three groups. Each group had two members.

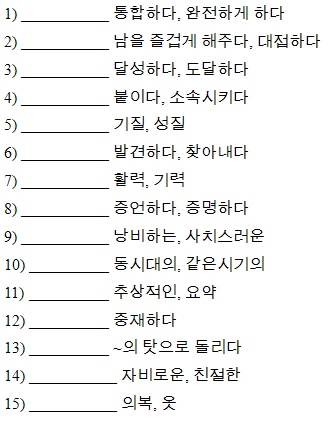

The target words in this experiment were drawn from an English vocabulary book which was designed for senior high school students (i.e., grades 10, 11, and 12) in Korea. From this book, 15 target words which had different affixes and roots were randomly drawn and the same target words were given to the students. The rationale for the selection of this book is that all the participants could have the same target words which were not familiar with.

This small study has three different instruction groups as follows; 1) guessing the meaning of new words in the context; 2) analyzing new words into affixes and roots to guess the meaning of new words without any context; and 3) pocket Electronic Bilingual dictionary look-up with written repetition. Three different instructions were randomly given to each group. Each group had 40 minutes to study the 15 target words according to their own vocabulary learning strategy and had 5 minute break before the test. After 5 minute break, all the participants took a 15 item matching test (see Appendix A). The same test was provided for each group.

The first group: Word Form Analysis group

There were 2 students who were in grade 5 and 6 respectively in this group. 15 target words were provided with the meanings of the appropriate prefixes, word roots, and suffixes of each word in English. They were asked to analyze the word and guess the meaning based on their analysis by themselves. After they completed their task, they were allowed to use bilingual dictionary to confirm their meanings. But they were not allowed to do verbal and written repetition for their retention.

The second group: Guessing the meaning of new words in the context

There were 2 students who were in grade 6 and 8 respectively in this group. 15 target words were provided with two meaningful contexts respectively per word. They were asked to guess the meaning of each word with the contexts given individually. After they finished their task, they were allowed to check their definitions together. They were allowed to ask me about the other unfamiliar words in the contexts. After they completed their task, they were allowed to use bilingual dictionary to confirm their meanings. But they were not allowed to do verbal and written repetition for their retention.

The third group: Pocket Electronic Bilingual Dictionary group

There were 2 students who were in grade 5 and 6 respectively in this group. 15 target words were provided without any affixes, word roots, and contexts. They were asked to look up the meanings of target words through a pocket bilingual dictionary and write down the definitions of the words. And then they were allowed to memorize the words and the corresponding definitions with written repetition.

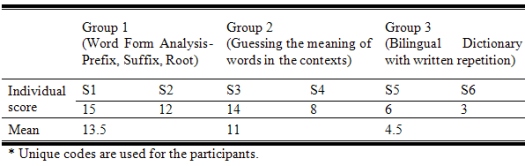

Table 1: The scores of each participant on a 15 point scale matching test

The results show that group 3 participants who used bilingual dictionary with written repetition got the lowest mark among the three groups. With regard to the results of group 1 participants, Park (2001) mentions that Korean learners of English agree that analyzing affixes and word roots would facilitate the development of their English vocabulary. Schmitt’s (1997) study also shows the Japanese students’ agreement with the use of word form analysis in their effective English vocabulary learning.

Concerning the results of group 2, Chin’s (1999) study with college students showed that context group got better marks than word form analysis group. This result can be explained by the age differences between two studies. Park (2001) also claims that older learners are likely to pay more attention to the use of contextual clues to guess the meaning of new words as they become cognitively grown up.

The results of group 3 might be explained by the assumption that the participants focused mainly on the spelling and exact definition of each word, because they had to memorize quite difficult new words within the very limited time. Since the test type was not informed to them in advance, they might have spent too much time on memorizing the form of each word. In addition, word by word definition-based vocabulary instruction might not be effective for L2 vocabulary learning, since there are no other clues such as word forms or contextual clues to help learners draw the lost meaning in this strategy when they lost the definition of a word.

Although the results of the above study show that word form analysis and guessing the meaning of new words in the context seemed to work better in Korean students’ English vocabulary learning, the results should not be interpreted statistically due to the very small number of the participants. Instead, the results along with the review of relevant literature might serve as a basis for suggesting teaching implications.

As Parry (1997) mentions, EFL teachers need flexibility in L2 vocabulary teaching strategies. Parry claims that EFL teachers should consider individual learners’ different learning habits, their cognitive development, and their different learning environments in the instruction of L2 vocabulary strategies. In addition, learners should not stick to just one or two main strategies to develop their L2 vocabulary.

The results in the study also reveal that strategies have an effect on learners’ L2 vocabulary learning. In this respect, teachers should teach learners appropriate strategies considering learners’ differences in their classrooms; otherwise learners will spend too much time on learning L2 vocabulary with inappropriate strategies.

In conclusion, this paper suggests that EFL teachers should take divers factors (e.g., learners’ needs and different learning behaviors, and different age levels) into deep consideration with flexibility instead of focusing on a specific strategy for L2 learners’ successful acquisition of their L2 vocabulary.

Chin, C. (1999). The effects of three learning strategies on EFL vocabulary acquisition. The Korea TESOL Journal, 2(1), 1-12.

Clarke, D. F., & Nation, I. S. P. (1980). Guessing the meanings of words from context: Strategy and Techniques. System, 8, 211-220.

Coady, J. (1997). L2 vocabulary acquisition through extensive reading. In J. Coady & T. Huckin (Eds.), Second language vocabulary acquisition (pp. 225-236). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kwon, O. (2000). Korea’s English education policy changes in the 1990s: Innovations to gear the nation for the 21st century. English Teaching, 55(1), 47-91.

Lightbown, Patsy M., & Nina Spada. (2006). How languages are learned (Third edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mochizuki, M., & Aizawa, K. (2000). An affix acquisition order for EFL learners: an exploratory study. System, 28, 291-304.

Nagy, W. (1997). On the role of context in first- and second-language vocabulary learning. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.), Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 64-83). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Park, J. (2001). Korean EFL learners’ vocabulary learning strategies. English Teaching, 56(4).

Parry, K. (1997). Vocabulary and comprehension: Two portraits. In J. Coady & T. Huckin (Ed.), Second language vocabulary acquisition. (pp.55-68). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press

Schmitt, N., & Meara, P. (1997). Researching vocabulary through a word knowledge framework: Word associations and verbal suffixes. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 20, 17-36.

Schmitt, N. (1997). Vocabulary learning strategies. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.),

Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 199-227). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Tang, G. M. (1997). Pocket Electronic Dictionaries for second language learning: Helping or hindrance? TESL Canada Journal, 15(1), 39-57.

| 1. attach |

2. integrate |

3. attain |

4. entertain |

5.detect |

| 6. temperament |

7. contemporary |

8.testify |

9. abstract |

10. intervene |

| 11. attribute |

12. extravagant |

13. benevolent |

14. garment |

15. vigor |

Write the number of each word on the line beside its meaning

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|