Virtual classrooms in foreign language learning - MOOs as rich learning environments

Lienhard Legenhausen & Markus Kötter, University of Münster

[editorial note: in HLT Yr 4, Issue 2 ,May 2002, Larry Davies published what you might call a sister article to this one: Do-it-yourself Humanism: courtesy of a blogger]

Menu

Introductory remarks

MOOs as rich learning environements

The educational potential of MOOs in foreign language learning

Concluding remarks

References and Resources

Introductory remarks

The introduction of networked computers in most educational institutions and private homes over the last few years has provided an ever increasing number of people with opportunities to develop their foreign language skills in ways that were almost unthinkable as recently as a decade ago. This paper discusses the potential of a fairly recent innovation in foreign language teaching, the MOO (or object-oriented Multiple-User Domain), for the development of learners' second language skills. MOOs evolved in the early 1990s from text-based computerised versions of Dungeons and Dragons board games, where people often had to slay dragons, find hidden keys, and rise to several other challenges to achieve the ultimate goal of the game, namely to become a so-called 'wizard'. However, today's educational MOOs, which are usually administered and maintained by a team of dedicated language teachers, are rather different from their predecessors.

A MOO allows people from around the globe to exchange messages they have typed on a computer in real time, and registered users can also create, manipulate and archive objects such as rooms, furniture and a host of text-based equivalents of classroom equipment like projectors, cameras, tapes, VCRs, and TV sets (cf. Schweller 1998: 97f) in the database. There are notice boards where students can leave a note for their peers, and MOO-internal editors allow them to collaborate on a text or even script and rehearse an entire presentation via the lecture tool. Unlike chat rooms, however, students and teachers can interact with each other within as well as across virtual rooms boundaries. They can paste even longer texts from and to MOO-internal text editors, and they can 'whisper' messages in order to spare others a potentially face-threatening situation.

We shall begin this paper with a few additional characteristics of MOOs that distinguish these text-based worlds from other virtual online environments and examine how these design features can be exploited successfully in approaches to language learning and teaching that put a particular emphasis on the development of students' communicative skills. We shall discuss some data we have collected over the past few years to illustrate how MOO-based discourse can affect learners' interactive (target) language skills, and we shall mention a number of references and scenarios that will hopefully lead to a further increase of the use of MOOs in language education.

1. MOOs as rich learning environments

Technically speaking, a MOO is simply a database hosted by a server that people access to exchange written messages with each other in real time, while they are surrounded by textual descriptions of objects such as rooms and artefacts that have also been created and stored in the database. At the same time, however, MOOs provide their users with such a unique sense of space, proximity and even intimacy that most users do conceptualise their interactions as real and authentic encounters in spite of the fact that they receive fairly little visual and no aural information about their interlocutors.

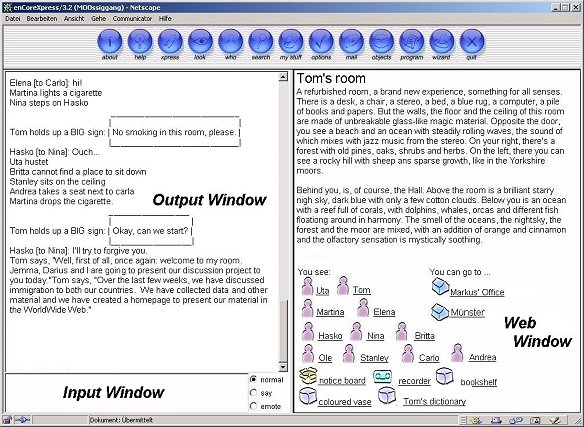

One design feature of the MOO environment that contributes to the sensation of space that visitors experience in this environment is the fact that locations in the MOO are permanent, and that they are linked together via entries and exists. People who enter a room are automatically provided with a textual description of what they 'see'-or rather, what they are expected to see, as it is up to the owners of a room to compose this text drawing on their own imagination. Furthermore, they can immediately check who and what else there is in a room. The EnCore client (Holmevik & Haynes 2000), an interface that converts some of these data into graphical information, displays this information as part of a tripartite screen (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Learner interactions in the EnCore-supported MOOssiggang MOO

The largest of the sections that are generated on a person's screen by the EnCore client is the so-called web window. This area, which can be arranged vertically or horizontally, cites the description of a room, while different icons indicate what else there is to see, including people, objects such as furniture, notes or recorders, and exits. Each icon contains an embedded hyperlink, and people can thus call up additional information about an object or person, or they can click on the symbol for an exit to change their virtual location to that mentioned next to the respective signpost.

The feedback that we have received from our learners suggests that the web window and the menu bar at the top of their screens, which are both fairly new extensions to traditional MOOs clients, are a great help to them, because they make navigating the environment and the manipulation of objects much easier than used to be the case when there were just two areas, the so-called input and output windows. The smaller area of these two, the input window at the bottom of the EnCore screen, allows learners to compose and revise the messages they want to exchange with other learners prior to sending them off via the Enter key, while the output window shows them what is happening in the environment. Here they can verify that the system has processed their data correctly, re-read their output and study what others have replied to their remarks, and this is also where status messages such as information about the arrival of a new person in a room are displayed.

What does this mean for the classification of the MOO as a rich learning environment? There are obviously numerous criteria that define what makes a particular situation, context or software package a rich learning environment. One crucial aspect is the suitability of the chosen tool or setting for the approach to language teaching and learning in which it is used, while other criteria include the ease with which learners can use available tools and the question of how comfortable they feel in and about a certain environment. It is important that there is a high level of authenticity in the tasks that learners are asked to complete and in the general framework within which they operate, and it is equally vital that the learners receive sufficient and suitable feedback on their performance.

Like in a chat room, but unlike a four-walled classroom, everyone in the MOO has an equal chance of speaking up since nobody can prevent another person from contributing to an ongoing discussion. This levelling off of status differences can have an extremely liberating effect on shy or timid students who would not dare to raise their hands in traditional classroom interactions (see also Sanchez 1996). Learners can take their time to compose a message, while the lack of visual information about themselves can likewise provide them with a feeling of ease and comfort that they may not necessarily experience in a face-to-face setting. The world-wide availability of the MOO allows teachers to hold classes or organise projects which bring together students in different physical locations and even from different continents, while the synchronous nature of MOO-based discourse enables students to request-and receive-instant feedback on their questions and comments.

Unlike talkers and similar tools, however, the spatial structure of a MOO means that learners can also branch out into different locations. Consequently, it is much easier for them and for their teachers to organise group work activities. Registered users can compose permanent profiles of their online personae, and many organisers of MOO projects have usually also asked their students to create rooms and artefacts as well as some of the text-based equivalents of the classroom tools that we have already mentioned above to make themselves at home in the MOO (e.g. Schneider & von der Emde 2000). In short, learners are not only provided with a sense of ownership that is often lacking in traditional classrooms, but they can also accommodate rather quickly to the environment.

We would even argue that MOOs offer a probably unique potential to trigger emotional engagement and immerse people in a discourse community that is nonetheless perceived as authentic and real rather than virtual reality. They allow learners to meet non-native (NNS) and even native speakers (NSs) of their target language in a "world of words" (Turner 2001) which is, on the face of it, full of artefacts and second-rate representations of reality. But the sensation of space they are experiencing in the MOO, the fact that they can choose from a much wider range of options to evoke and (re-)create an impression of proximity and even intimacy, and the condition that their interlocutors are nevertheless real people provide teachers (and learners) with such a variety of options to engage in meaningful interactions that MOOs must be placed high on any list of currently available rich learning environments.

2. The educational potential of MOOs in foreign language learning

MOOs reduce the complex reality of a four-walled classroom to just a handful of text-based objects, and the same is more or less true for the ways in which people can frame their output. They can 'say' something, address their turns directly to individuals, exchange page messages, hold up 'big boards', and they can use the emote command to narrate-and thus perform-actions as diverse as laughing, gesturing or poking someone in the ribs even if the addressee of their actions may be literally thousands of miles away on a different continent; the passage below cites the beginning of one of our students' presentations in the MOO:

Elena [to Carlo]: hi!

Martina lights a cigarette

Nina steps on Hasko

Tom holds up a BIG sign:

___________________________________

| No smoking in this room, please. |

|__________________________________|

Hasko [to Nina]: Ouch...

Uta hustet

Britta cannot find a place to sit down

Stanley sits on the ceiling

Andrea takes a seat next to carla

Matina drops the cigarette.

Tom holds up a BIG sign:

______________________

| Okay, can we start? |

|_____________________|

Hasko [to Nina]: I'll try to forgive you.

Tom says, "Well, first of all, once again: welcome to my room. Jemma, Darius and I are going to present our discussion project to you today." Tom says, "Over the last few weeks, we have discussed immigration to both our countries. We have collected data and other material and we have created a homepage to present our material in the WorldWide Web."

In some respects, this apparent paucity of the MOO can certainly be interpreted as a negative. We would, however, argue that the need for learners to study their partners' comments and to engage in almost constant reading 'between the lines' is in effect a notable asset of this innovative learning environment. Not only are learners obliged to 'verbalise' everything they want to share with their partners, including paralinguistic information, which would otherwise go unnoticed, but they also have to reconstruct the intention behind others' contributions on the basis of a rather limited amount of information.

There is plenty of evidence in the data we have collected over the last few years to demonstrate that MOOing 'works', that the added emphasis on linguistic input and output in the MOO sensitises learners to the language their partners have used, and we also found that the reduced set of communicative options that learners had at their disposal in the MOO prompted them to monitor and reflect upon their own linguistic repertoire. Indeed, the feedback one of us obtained from students who participated in a one-term tandem partnership involving NNSs of German and English was replete with comments like the following: "I found that I had to be very careful with what I said and how I said it so as not to be misunderstood. Especially when it came to sarcasm and joking around." (Kötter 2002:112). But engagement in MOO discourse also allows learners to exploit the less face-threatening nature of the online environment to appeal for various types of help. They can ask others about the meaning of an unknown word or phrase, request a clarification, and even open up a dictionary in the web window without their teacher or partner(s) ever noticing that they have done so:

Maren says, Kunst und Wissenschaft, Forschung und Lehre sind frei. Die Freiheit der Lehre entbindet nicht von der Treue zur Verfassung.

Sonja [to Joanne/Jack]: Do understand the first part?

Jack says, Art and Science, ??? and teaching are free. The freedom of teaching is not bound from the truth of the constitution???

Jack says, help!

Maren [to Jack]: Yes

Sonja says, It says that tha Arts ans Sciences are free

Jack says, what is forschung

Maren [to Jack]: Forschung is what you should do at university

Jack says, study?

Sonja [to Jack]: Forschung is a kind of investigations.

Deanna says, Hmmm... this is interesting. So the document does not say that people MUST support the Arts?

Jack says, Research=Forschung?

Sonja nods.

Maren says, Rather research than study

Jack says, okay. and the second part... let me try

This passage from a discussion between four German and American students who participated in the online tandem exchange already mentioned above illustrates how NNSs can draw on their partners' expertise as native speakers of their respective target language in the MOO, and how similar this type of discourse often is to verbal interactions. But it also demonstrates how more capable partners can scaffold their peers' task and thus how well the MOO leads itself to approaches based on sociocultural theory and constructivist perspectives (Bruner 1986; Schwienhorst 1998).

Encounters in the MOO provide learners with numerous opportunities to engage in negotiation of meaning and to practise routines such as asking for clarifications, check that others have understood what they said, and re-formulations of their own ideas in response to requests for repetitions or paraphrases. They do, however, also necessitate the co-construction of social reality, and it is quite obvious that the combination of animated discussions and gaps in learners' commands of their target language(s) can lead to misunderstandings or even disagreements and potentially serious conflicts. Still, the negotiations that follow these incidents do often provide students with valuable additional insights into the management of communicative processes, and they occasionally also throw up significant information about cultural stereotypes and the reasons behind their partners' aggression or dissatisfaction.

Lee says, "You would need to save your picture as: Corinna.JPG"

CORINNA says, "I'm too old for this. What does JPG snad for?"

Karina says, "Jelly Picture Good."

CORINNA says, "a-ha"

Lee says, "oder...gif"

CORINNA says, "You'll get the picture anyway."

Karina says, "it's just when you scan a picture in, it can be in jpg or gif format"

CORINNA says, "Okay, excuse my lack of common knowledge..."

Karina says, "not excused"

CORINNA sulks, sits in a corner and doesn't look at anyone any more

Karina does the same thing auf Deutsch.

Lee babysits

CORINNA says, "Nachaeffer"

Lee says, "aeffer?""

CORINNA says, "Aeffer comes from "Affe"=monkey... it means imitating someone in a silly way"

Karina says, "Oh yeah...that was in chapter one freshman year. It's the first german word we learned."

This passage presents a situation in which two American learners, Karina and Lee, teased their German partner Corinna about her lack of familiarity with computers. Corinna initially responded to this challenge with a few good-hearted and actually rather witty remarks. She mocked her own incompetence ("I'm too old for this"), played with the inherent ambiguity of the phrase 'get the picture', and she even tried to defuse the conflict that threatened to arise from Karina's "not excused" by switching to emoting and by appealing to her partners for comfort. Still, Karina's alleged imitation of Corinna's behaviour and Lee's "babysitting" did nothing to defuse the situation, and it was only Corinna's switching to German that appears to have appeased Lee, who suddenly had admit to her ignorance in a different field of discourse-her target language-that seems to have settled the issue on this occasion.

All three students continued to discuss their presentation amicably after this incident, although it is perhaps also worth pointing out that none of the students apologised for their behaviour. Even more importantly, however, we see that this episode, which started out with a potential conflict, ultimately enabled Karina and Lee to expand their vocabulary, and the exchange thus demonstrates quite powerfully what Turbee (1996), one of the earliest proponents of the use of MOOs in language education, once described as follows:

It is thinking, in writing and in the target language, but in response to another human being. The greatest appeal of MOO is the endless variety of human response and the social nature of the learning experiences.

Concluding remarks

MOOs can provide teachers with virtual classrooms that can be used for traditional small-group work, but which nonetheless demand a fairly radical breaking away from traditional pedagogies. They give learners more freedom to explore-and play with-their native and with their target language than traditional classroom discourse, allow them to engage in real time conversations with non-native speakers of their target language, and they provide an almost ideal practice ground for awareness-raising activities that range from reflections upon the proximity between spoken language and written online discourse to strategies that learners need to acquire for successful discourse management.

MOO projects require careful planning, and Haynes' (1998) has put together an excellent check list for anyone who plans to take students to this virtual world. However, the trouble of preparing such an enterprise is well worth the effort, as can be seen from several projects that we haven't even had time to mention until now. In addition to MOOs There are numerous other aspects of MOOing that o the development of learners' linguistic and metalinguistic skills that we cannot discuss in much detail in a paper as short as this, including the various ways in which teachers and learners can exploit the electronic transcripts of online encounters (English 1998), the role of codeswitching in discussions between native speakers and non-native speakers in an online tandem partnership, and the exploitation of the MOO in role-playing activities, a simulation globale or the scripting and performance of entire plays (Burk 1998). Likewise, there remains much to say about the potential of MOOs as venues for collaborative writing exercises (Crump 1998), the ideal combination of online and off-line activities, and the role that MOOs can play in cultural studies and the development of 'autonomous' learners.

References

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Burk, J. (1998). "The play's the thing: Theatricality and the MOO environment." In: Haynes, C. & Holmevik, J. R. (eds.). High wired. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. 232-249.

Crump, E. (1998). "At home in the MUD: Writing centers learn to wallow." In: Haynes, C. & Holmevik, J. R. (eds.). High wired. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. 177-191.

English, J. A. (1998). "MOO-based metacognition: Incorporating online and offline reflection into the writing process." Kairos Journal. http://english.ttu.edu/kairos/3.1/features/english/intro.html; retrieved 17 October 2002.

Holmevik, J. R. & Haynes, C. (2000). MOOniversity. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Kötter, M. (2002). Tandem learning on the Internet: Learner interactions in virtual online environments (MOOs). Frankfurt: Lang.

Sanchez, B. (1996). "MOOving to a new frontier in language teaching." In: Warschauer, M. (ed.). Telecollaboration in foreign language learning. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i, Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center. 145-164.

Schneider, J. & von der Emde, S. (2000). "Brave new (virtual) world: Transforming language learning into cltural sudies through oline learning environments (MOOs)." ADFL Bulletin 32 (1), 18-26.

Schweller, K. (1998). "MOO educational tools." In: Haynes, C. & Holmevik, J. R. (eds.). High wired. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. 88-106.

Schwienhorst, K. (1998). "The 'third place'- virtual reality applications for second language learning." ReCALL 10 (1), 118-126.

Turner, J. (2001). "Worlds of words: Tales for language teachers." In: Felix, U. (ed.). Beyond Babel. Melbourne: Languages Australia. 163-186.

Resources

MOOssiggang can be accessed via http://moo.vassar.edu:7000/

|